Illuminating the Objective Psyche

-

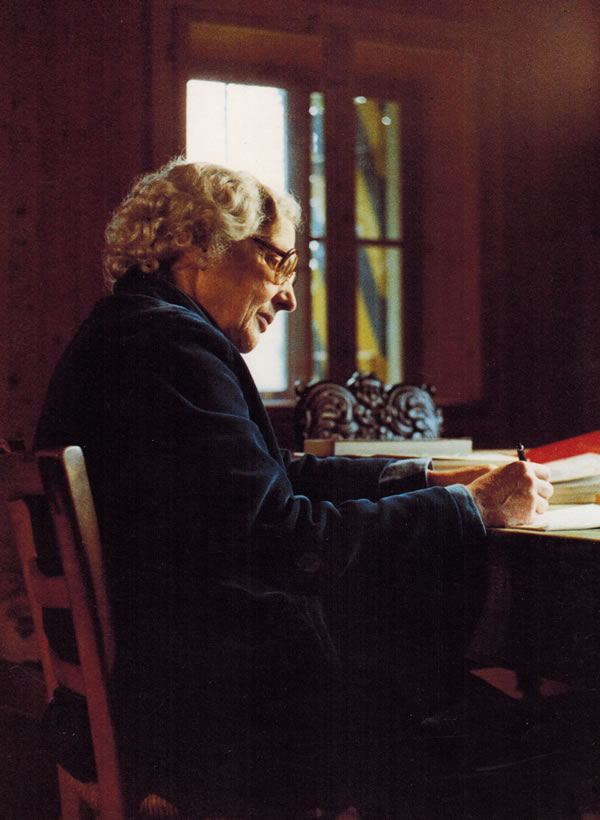

Who was Marie-Louise von Franz?

Marie-Louise von Franz (1915-1998) was a pioneering Jungian analyst, scholar and author who made profound contributions to the field of analytical psychology. As a close collaborator of Carl Jung for over 30 years, von Franz helped shape and expand many of his seminal concepts. At the same time, she was an original thinker who opened up new domains of Jungian theory and practice, particularly in the interpretation of fairy tales, alchemy, and number symbolism. Her prolific writings and lectures mapped the furthest reaches of the collective unconscious, illuminating the objective psyche and its manifestations in human culture.

- Books: The Interpretation of Fairy Tales Amazon

- YouTube Lecture: Marie-Louise von Franz on Dreams

- Biography: Marie-Louise von Franz’s Life

- Interview: In Conversation with von Franz

- Podcast: Marie-Louise von Franz on Fairy Tales

- Article: von Franz on Jung and Alchemy

- Institute: Marie-Louise von Franz at the C.G. Jung Institute

- Research: Publications by von Franz

- Quotes: von Franz Quotes

- Archive: von Franz Archive

Main Ideas and Key Concepts:

- Von Franz was a leading interpreter of Jung’s concept of the objective psyche – the innate, universal layer of the unconscious that is the source of archetypal images, patterns and instincts.

- She helped develop Jung’s method of amplification, showing how mythological motifs and symbols can be used to unpack the meaning of dreams, fantasies and creative works.

- Von Franz was a major scholar of alchemy, illuminating its symbolic processes as analogies for individuation and the integration of the psyche.

- Fairy tales were central to her work – she saw them as pristine expressions of archetypal patterns, providing maps for the individuation journey.

- She pioneered the psychological interpretation of number symbolism, revealing the qualitative aspects of numbers and their role in ordering psychic energy.

- The inferior function and the problem of evil were major themes in her analysis of the shadow and the archetypal forces behind human destructiveness.

- Von Franz explored synchronicity extensively, seeing it as an “acausal connecting principle” that reveals the meaningful patterning of psyche and matter.

- Her work on projection and the “not-I” within the psyche shed light on the complex dynamics of relationships and the need to withdraw shadow projections.

- Individuation, for von Franz, was an impersonal process in which the ego is relativized to the Self, the archetype of wholeness at the core of the psyche.

- Her reflections on the animus and anima extended Jung’s understanding of contra-sexual archetypes and their role in the dialectic of individuation.

- She explored the religious function of the psyche and the archetypal basis of esoteric traditions like Gnosticism, connecting depth psychology and spirituality.

Jungian Innovators

The Objective Psyche and the Collective Unconscious

At the heart of von Franz’s work was Jung’s concept of the objective psyche – the innate, transpersonal layer of the unconscious that is the wellspring of psychic life. In contrast to the personal unconscious shaped by individual history, the objective psyche is universal and autonomous, filled with primordial images and instinctual patterns that manifest across cultures and eras.

Von Franz saw the objective psyche as the empirical basis for Jung’s theory of archetypes. Archetypes, she argued, are not mere concepts but living psychic realities – dynamic nodal points in the collective unconscious that structure human experience. Like riverbeds that direct the flow of a stream, archetypes channel psychic energy into typical patterns of behavior, emotion and imagination. They manifest in the motifs of myths and fairy tales, the themes of literature and art, and the symptoms of neurosis and psychosis.

To von Franz, the autonomy of the objective psyche was decisive. It meant that archetypal phenomena were not merely subjective projections but had an independent existence in the depths of the psyche. Dreams, for example, were not just reflections of personal issues but contained objective, even prophetic messages from the unconscious. Similarly, creative inspiration was not a purely personal achievement but a gift from the autonomous depths – a “dictation” from the objective psyche.

This understanding had crucial implications for psychological method. It meant that the interpretation of dreams, fantasies and creative works required more than personal associations – it demanded a symbolic approach that could unpack their objective meaning. To this end, von Franz helped develop Jung’s technique of amplification, showing how mythological parallels could be used to decipher the archetypal significance of an image or motif.

Amplification involved collecting analogies to a symbol from comparative mythology, anthropology, history and other fields – and using these to “circumambulate” its essential meaning. By gathering a wide net of parallels, the unique contours of the archetype could be discerned, like a figure emerging from the mist. The point was not to reduce the symbol to a fixed concept but to unfold its living reality, to convey a felt sense of the objective psychic situation.

For von Franz, this approach honored the numinosity and mystery of the archetypal realm. It recognized that the objective psyche was ultimately beyond the grasp of the ego, with its own intentions and agenda. The task of Jungian psychology was to cultivate a respectful dialogue with this autonomous dimension – to listen humbly to the messages of the unconscious and align with its deeper wisdom. In a sense, the analyst served as a mouthpiece for the objective psyche, translating its symbolic language into themes to inform a more conscious individuation.

Alchemy and the Transformation of the Psyche

One of von Franz’s major contributions was her psychological exegesis of alchemy, the ancient art of transforming base metals into gold. Picking up where Jung left off, she saw the alchemists’ opus as a symbolic representation of the individuation process – the journey towards wholeness and Self-realization.

The stages of the alchemical work, from the initial nigredo (blackening) to the final rubedo (reddening), mirrored the archetypal process of psychological transformation. The nigredo evoked the dark night of the soul, the descent into the shadows of the unconscious. The albedo (whitening) suggested the purification of consciousness, the burning away of dross and complexes. The rubedo signaled the dawn of the Self, the rise of a new, integrated personality.

Von Franz explored these parallels in her seminal works “Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology” and “Aurora Consurgens,” a commentary on an alchemical treatise attributed to Thomas Aquinas. She showed how the cryptic symbolism of the alchemists expressed deep psychological truths, anticipating many of Jung’s key concepts.

For example, the mercurial spirit that animated matter corresponded to the objective psyche and its autonomous dynamism. The philosophers’ stone, the goal of the opus, represented the archetype of the Self, the supreme symbol of wholeness. The alchemical hermaphrodite, the fusion of masculine and feminine, paralleled the syzygy of animus and anima in the psyche. And the sacred marriage of opposites evoked the coniunctio, the supreme union of conscious and unconscious.

By decoding these motifs, von Franz shed light on the archetypal roots of the individuation journey. She showed how alchemy provided a symbolic map for the ego’s encounter with the unconscious, its descent into the depths and ultimate transformation by the Self. The opus was not just a chemical procedure but a spiritual discipline, a “yoga of the West” that aimed at the transmutation of the soul.

At the same time, von Franz was careful not to reduce alchemy to a mere psychological allegory. She honored its concrete, physical dimension, seeing the work with matter as a critical counterpart to inner transformation. The alchemists’ engagement with the substances of nature grounded their spiritual quest, anchoring it in the embodied world.

In this sense, alchemy pointed to the mysterious interface of psyche and matter, the point where inner and outer worlds meet. It suggested that the processes of individuation are not just psychological but have a cosmic dimension, reflecting the greater alchemy of nature itself. By studying the alchemists’ opus, von Franz gained insight into the objective, archetypal foundations of transformation – the universal patterns that underlie growth and change.

These insights had profound implications for the practice of depth psychotherapy. They suggested that the task of therapy is not just to resolve personal conflicts but to facilitate the individuation process – to align the ego with the natural unfolding of the Self. Just as the alchemists submitted to the transformative powers of nature, the therapist must humble herself before the objective psyche, serving as a midwife to its autonomous agenda.

At the same time, alchemy pointed to the importance of creative expression and active imagination in the individuation journey. Just as the alchemists projected their inner dramas onto matter, working them out in the lab, the analysand must give form to the contents of the unconscious – through art, writing, dance and other symbolic practices. By shaping the raw materials of psyche, one participates in the opus of transformation, birthing the philosophers’ stone of the Self.

The Wisdom of Fairy Tales

Fairy tales were another central focus of von Franz’s work. She saw these ancient stories as some of the purest expressions of archetypal patterns, providing a direct window into the objective psyche. Unencumbered by personal or cultural overlays, fairy tales presented the basic structures of the collective unconscious in all their numinous power.

In her groundbreaking books “The Interpretation of Fairy Tales” and “The Feminine in Fairy Tales,” von Franz developed a systematic approach to the psychological analysis of these stories. Drawing on her encyclopedic knowledge of world mythology, she showed how the motifs of fairy tales corresponded to universal patterns of psychic development.

For example, the hero’s journey – from humble beginnings through trials and ordeals to ultimate triumph – mirrored the archetypal process of individuation. The hero’s battle with dragons and monsters evoked the ego’s confrontation with the shadow, while his ultimate union with the princess represented the integration of anima/animus. The magical objects and helpers the hero encountered along the way symbolized the numinous resources of the Self, the inner allies that guide the individuation journey.

By unpacking these themes, von Franz revealed the hidden wisdom of fairy tales – their power to orient us in the labyrinth of the psyche. She showed how these stories provide a symbolic map of the individuation process, charting the universal challenges and opportunities of psychological growth. At the same time, she demonstrated how the details of a given tale could shed light on the specific dynamics of a personal situation, illuminating the archetypal underpinnings of an individual’s struggles and dreams.

Central to von Franz’s approach was the idea that fairy tales are not just quaint relics of a primitive past but living entities with relevance for the present. She saw them as emanations of the objective psyche, carrying timeless messages for the modern soul. By engaging with these stories – through active imagination, dream interpretation, or creative retellings – we can tap into the archetypal wellsprings of transformation, aligning ourselves with the deeper currents of psychic life.

At the same time, von Franz was careful not to reduce fairy tales to a set of fixed meanings or psychological formulas. She honored the irreducible mystery and complexity of these stories, recognizing that they spoke to multiple layers of the psyche. A fairy tale might have a different meaning depending on the psychological situation of the reader, revealing new facets and dimensions with each encounter.

In this sense, fairy tales were not just objects of interpretation but living presences with their own autonomy and agency. They had the power to move and transform the psyche, to catalyze growth and change in ways that surpassed intellectual understanding. By approaching them with an attitude of wonder and receptivity, one could enter into a dialogical relationship with the objective psyche, allowing oneself to be moved and guided by its numinous wisdom.

For von Franz, this approach to fairy tales exemplified the essence of the Jungian method. It involved a surrender of the ego to the greater powers of the psyche, a willingness to be transformed by the archetypal realities that underlie human experience. By immersing oneself in the universal language of symbols, one could align with the deepest currents of the individuation process, tapping into the regenerative powers of the Self.

In the end, von Franz’s work with fairy tales was not just an intellectual exercise but a spiritual discipline, a way of attuning to the objective foundations of the psyche. It demanded a stance of humility and reverence before the autonomous depths, a recognition of the limits of ego-consciousness. At the same time, it pointed to the transformative potential inherent in these depths – the power of archetypal symbols to heal and whole the fragmented modern soul.

Number and Archetype: The Psychological Meaning of Numbers

In addition to her work on alchemy and fairy tales, von Franz was a pioneer in the psychological interpretation of numbers. Drawing on Jung’s concept of the archetypes, she argued that numbers are not just quantitative tools but carriers of qualitative meaning, reflecting fundamental patterns of psychic organization.

Von Franz’s magnum opus in this area was “Number and Time,” a dense and challenging book that explored the archetypal symbolism of numbers across cultures and eras. Using examples from mythology, philosophy, science and other fields, she showed how numbers have served as numinous vessels for the archetypal configurations of the objective psyche.

For example, the number one – the monad – represented the primal unity and wholeness of the Self, the undivided source from which all multiplicity springs. The dyad (two) evoked the archetypal polarity of opposites – masculine/feminine, light/dark, conscious/unconscious – and their dynamic interplay. The triad (three) suggested the mediating function that reconciles opposites, the “third” that creates a new synthesis. The quaternity (four) represented completeness and stability, the solid foundation of psychic order.

By unpacking these archetypal meanings, von Franz shed light on the psychological significance of numbers in human culture. She showed how numerical patterns have structured our myths, traditions and belief-systems, giving form to the basic constituents of the objective psyche. At the same time, she demonstrated how an understanding of number symbolism could deepen our appreciation of the archetypal underpinnings of modern thought, from the binary code of computers to the quantum equations of physics.

Central to von Franz’s approach was the idea that numbers are not just mental constructs but autonomous entities with their own reality and agency. Like the archetypes themselves, numbers have a numinous power and presence that transcends individual consciousness. They are, in a sense, the skeletal framework of the objective psyche, the basic building blocks of psychic order.

This understanding had profound implications for the practice of Jungian psychology. It suggested that the language of number could provide a direct access to the archetypal realm, bypassing the distortions of ego-consciousness. By attuning to numerical symbolism – whether through dream interpretation, active imagination, or mathematical reflection – one could align with the deep structures of the psyche, tapping into the ordering principles of the Self.

At the same time, von Franz’s work challenged the modern tendency to reduce numbers to mere quantities, devoid of qualitative significance. In a world increasingly dominated by the abstract calculations of science and technology, she argued for a renewed appreciation of the psychological dimension of number – its power to convey meaning, value and numinosity.

This critique had political implications as well. Von Franz saw the rise of mass society and totalitarianism as symptoms of a one-sided, quantitative worldview that reduced individuals to mere statistics, cogs in the machine of the state. By reconnecting with the qualitative, archetypal essence of number, she suggested, we could resist these dehumanizing trends, affirming the irreducible value and uniqueness of the individual soul.

Ultimately, von Franz’s work on number symbolism was an expression of her lifelong commitment to the “reality of the psyche” – the autonomous, objective dimension of inner life that transcends personal consciousness. By revealing the archetypal foundations of this dimension, she helped to map the deepest structures of the human experience, illuminating the universal patterns that shape our individual journeys.

At the same time, her work challenged us to broaden our understanding of what constitutes “reality,” beyond the narrow confines of material existence. It pointed to a more expansive vision of the cosmos, one that includes the numinous, archetypal realm as a fundamental aspect of the whole. By honoring this dimension – in our psychology, our science, and our culture at large – we can create a world that is more aligned with the deep wisdom of the psyche, more attuned to the objective foundations of meaning and value.

The Inferior Function and the Problem of Evil

The problem of evil was another major theme in von Franz’s work. Drawing on Jung’s concept of the shadow, she explored the psychological roots of human destructiveness – the archetypal forces that drive individuals and groups to commit acts of violence, cruelty and oppression.

For von Franz, the key to understanding evil lay in the dynamic of the inferior function – the least developed and most unconscious of the four psychological functions (thinking, feeling, sensation, intuition). According to Jungian theory, the inferior function is the Achilles heel of the psyche, the point of greatest vulnerability and weakness. It is the function that we most neglect and repress, the one that falls into the shadow of the unconscious.

Von Franz argued that the inferior function is the breeding ground for evil, the psychic terrain where the darkest aspects of the shadow take root. When the inferior function is chronically repressed, it becomes a source of toxic energy, a festering wound that infects the whole personality. The psyche is forced to split-off and project this energy onto others, leading to a range of destructive behaviors – from scapegoating and demonization to outright violence and sadism.

In her book “The Problem of the Puer Aeternus,” von Franz explored this dynamic in relation to the archetype of the eternal youth – the man-child who refuses to grow up and take responsibility for his life. She showed how the puer’s one-sided identification with the superior function (usually thinking or intuition) led to a neglect and repression of the inferior function (usually sensation or feeling). This created a dangerous imbalance in the psyche, fueling destructive behaviors such as narcissism, grandiosity, and an inability to relate to others. The puer’s undeveloped feeling function, in particular, left him prone to cold-heartedness and cruelty, cut off from the humanizing influence of empathy and compassion.

Von Franz saw a similar dynamic at work in the psychology of totalitarianism. She argued that fascist and communist regimes were fueled by a collective repression of the inferior function, with whole societies splitting off their vulnerability and projecting it onto demonized others. The result was a kind of mass psychosis, a descent into brutality and inhumanity on an unimaginable scale.

To counter these destructive tendencies, von Franz emphasized the need for a conscious integration of the inferior function. She saw this as a critical aspect of the individuation process – the work of psychologically differentiating and balancing the four functions, uniting them around the Self. By embracing our least developed side, we diminish the shadow’s power, reclaiming the lost parts of our humanity.

This process, however, is far from easy. It demands a willingness to confront the darkness within, to take responsibility for the evil that lurks in the depths of the psyche. It requires a surrender of the ego’s defenses, a humble recognition of our own capacity for destructiveness. Only by owning our inferior function can we begin to transform it, channeling its energies in a more constructive direction.

For von Franz, this meant cultivating a kind of psychological humility – a respect for the autonomous powers of the unconscious and a willingness to learn from them. It meant developing a dialogical relationship with the inferior function, treating it not as an enemy to be conquered but as a neglected part of the self that needs to be heard and integrated.

At the same time, von Franz cautioned against a naïve embrace of the shadow, warning of the dangers of wallowing in darkness or romanticizing evil. The goal was not to identify with the inferior function but to relate to it consciously, using the light of understanding to transform its raw energies. This required a delicate balance of acceptance and discernment, a capacity to hold the tension of opposites without falling into one-sidedness.

Ultimately, von Franz saw the integration of the inferior function as a moral imperative, a necessary step in the evolution of human consciousness. By confronting the evil within, we take responsibility for our own darkness, diminishing its destructive impact on the world. At the same time, we tap into a deeper source of creativity and transformation, unleashing the healing potential of the Self.

In a world torn apart by violence and division, this message has a profound urgency. It challenges us to look beyond simplistic notions of good and evil, recognizing the complex interplay of light and shadow within the human soul. It calls us to a new level of psychological maturity, one that can hold the ambiguities and contradictions of existence without resorting to projection or scapegoating.

By taking up this challenge, we can begin to heal the rifts that divide us, both within and without. We can learn to relate to the “other” not as an enemy to be destroyed but as a mirror of our own unacknowledged depths. And we can work towards a more integrated world, one that honors the full spectrum of human experience, from the heights of our potential to the depths of our frailty and fallibility.

Synchronicity: The Acausal Connecting Principle

Von Franz was a leading interpreter of Jung’s concept of synchronicity – the meaningful coincidence of inner and outer events. She saw synchronicity as a key to understanding the interconnectedness of psyche and matter, the mysterious interface where the archetypal realm meets the physical world.

In her book “On Divination and Synchronicity,” von Franz explored the historical and cross-cultural manifestations of this phenomenon, from ancient oracles to modern parapsychology. She showed how synchronicities have been experienced and interpreted in diverse contexts, revealing a universal human fascination with the acausal dimension of reality.

For von Franz, synchronicity was not just a curious anomaly but a fundamental aspect of psychic life. She saw it as an expression of the objective psyche’s holistic patterning, the way that archetypal meanings weave themselves into the fabric of existence. When an outer event mirrors an inner state with uncanny precision, it reveals the deeper unity of mind and matter, the underlying matrix that connects all things.

This understanding had profound implications for the practice of Jungian psychology. It suggested that the psyche is not just a subjective, inner reality but a participatory agent in the larger unfolding of the cosmos. Our dreams, fantasies and symbolic experiences are not just private musings but part of a greater web of meaning, a conversation between the individual and the anima mundi, or world soul.

By attending to synchronicities – whether in therapy, art, or everyday life – we can attune ourselves to this greater conversation, aligning with the deeper patterns that guide the individuation process. We can learn to read the “signs” that punctuate our lives, using them as a compass for navigating the uncharted waters of the unconscious.

At the same time, von Franz warned against a simplistic or superstitious approach to synchronicity. She emphasized that not every coincidence is meaningful, and that it takes a trained eye to discern the difference. The task is not to seek out synchronicities but to cultivate an attitude of openness and receptivity, allowing them to emerge naturally in the course of one’s inner work.

This attitude demands a certain humility, a willingness to surrender our ego’s need for control and understanding. Synchronicities often confound our rational expectations, pointing to a dimension of reality that transcends linear causality. By embracing this mystery, we open ourselves to a more enchanted and participatory worldview, one that recognizes the numinous depths of psyche and cosmos.

For von Franz, this worldview had ethical and spiritual implications as well. By revealing the interconnectedness of all things, synchronicities challenge us to live with greater empathy and responsibility, recognizing the impact of our actions on the larger web of life. They remind us that we are not isolated egos but part of a greater whole, participants in a cosmic dance of meaning and transformation.

Ultimately, von Franz’s work on synchronicity invites us to a radical re-visioning of reality, one that bridges the split between mind and matter, inner and outer, psyche and world. It points to a new kind of science, one that honors the subjective and symbolic dimensions of experience alongside the objective and quantitative. And it calls us to a new kind of spirituality, one that grounds transcendence in the depths of the psyche and the concrete realities of the embodied world.

By taking up this vision, we can begin to heal the dissociations of the modern mind, reconnecting with the living mystery at the heart of existence. We can learn to navigate by synchronicity, aligning our lives with the greater unfolding of the Self, both personal and planetary. And we can work towards a more enchanted and participatory world, one that honors the full spectrum of human experience, from the rational to the numinous, the causal to the acausal, the mind to the heart.

Individuation and the Self

The concept of individuation was central to von Franz’s understanding of psychological development. Building on Jung’s work, she saw individuation as the innate drive towards wholeness and self-realization that guides the human life cycle. It is the process by which we become who we truly are, differentiating ourselves from the collective and realizing our unique potential.

For von Franz, individuation was not about the development of the ego but about its relativization to the Self – the transpersonal center of the psyche that Jung called the “God within.” The Self is the archetype of wholeness, the regulating principle that unites the various parts of the personality around a common center. It is the source of our deepest values and aspirations, the inner compass that guides us towards our true north.

Individuation, then, is the process of aligning ego with Self, of bringing our conscious personality into greater harmony with the unconscious depths. It is a journey of self-discovery and transformation, a spiral path that leads us ever closer to the core of our being. Along the way, we encounter the various archetypes and complexes that make up the inner landscape of the psyche, from the shadow and the anima/animus to the great mother and the wise old man.

For von Franz, this journey was not a linear ascent but a dialectical process of crisis and renewal, death and rebirth. She saw individuation as a series of initiatory ordeals, each one stripping away the false identities and limiting beliefs that obscure the Self. These ordeals might take the form of a midlife crisis, a dark night of the soul, or a confrontation with the shadow. They plunge us into the depths of the unconscious, forcing us to face the rejected and undeveloped parts of ourselves.

If we have the courage to endure these descents, however, we emerge transformed, reborn into a larger sense of selfhood. We discover new sources of meaning and creativity, new ways of being in the world that reflect our deepest values and aspirations. We become more authentic and autonomous, less driven by external expectations and more guided by an inner sense of purpose.

At the same time, von Franz emphasized that individuation is not a purely personal or solitary journey. It is always embedded in a larger social and cultural context, shaped by the collective values and beliefs of our time. To truly individuate, we must also differentiate ourselves from the mass mind, the herd mentality that conforms to the status quo. We must learn to think for ourselves, to question the dominant assumptions of our society and forge our own path.

This can be a lonely and challenging road, one that demands great moral courage and integrity. It means standing up for what we believe in, even when it goes against the grain of collective opinion. It means being willing to be an outsider, a voice in the wilderness that speaks truth to power. And it means cultivating a deep sense of empathy and concern for the greater good, recognizing that our individual fulfillment is inextricably linked to the wellbeing of the whole.

Ultimately, von Franz saw individuation as a spiritual journey, a quest for meaning and purpose that leads us beyond the confines of the ego to the larger reality of the Self. It is a journey of self-transcendence, of surrendering our attachment to the “I” in order to serve the greater “We.” By aligning ourselves with the Self, we become channels for its transformative power, vessels for the healing and renewal of the world.

In this sense, individuation is not just a personal imperative but a collective one as well. In a time of global crisis and upheaval, it has become an urgent necessity – a way of tapping into the wisdom and creativity that can guide us through the challenges ahead. By committing ourselves to this journey, we can become agents of transformation, midwives of a new era that is more just, compassionate, and sustainable.

As von Franz reminds us, this is no easy task. It demands a willingness to confront the shadows within and without, to face the pain and darkness of the world with an open heart. It requires a deep faith in the regenerative power of the psyche, a trust in the greater intelligence that guides the individuation process. And it calls us to a radical humility, a recognition of our own limitations and the ultimate mystery of existence.

But if we can rise to this challenge, the rewards are immeasurable. We discover a sense of purpose and belonging that transcends the ego, a connection to the greater web of life that sustains and nourishes us. We tap into the wellsprings of creativity and resilience that can help us weather any storm. And we become part of a larger story, a collective journey of awakening that has the power to transform the world.

In the end, von Franz’s vision of individuation invites us to a new kind of heroism – not the heroism of conquest and domination, but the heroism of self-knowledge and service. It calls us to become the change we wish to see in the world, to embody the values of the Self in our own lives and communities. And it reminds us that, even in the darkest of times, there is always a light that guides us home, a truth that sets us free. May we have the courage to follow that light, to stay true to our deepest purpose, and to become the individuals we were meant to be.

9. The Animus and Anima: Contra-sexual Archetypes

Von Franz made significant contributions to Jung’s theory of the animus and anima – the contra-sexual archetypes that represent the unconscious masculine and feminine qualities in women and men, respectively. She saw these archetypes as critical components of the individuation process, bridging the gap between the conscious personality and the deeper layers of the psyche.

For von Franz, the animus and anima were not just personal complexes but archetypal structures that shape our experience of gender and relationship. They are the psychic templates that guide our projections and attractions, the inner figures that we seek to embody and unite with in the outer world.

In women, the animus represents the unconscious masculine – the qualities of logos, order, and directed thought that complement the feminine eros. When integrated, the animus can be a source of creative inspiration and spiritual wisdom, a bridge to the transcendent dimensions of the Self. But when undeveloped or possessed, it can manifest as negative masculinity – as a critical, dominating inner voice that undermines the woman’s sense of self-worth and authenticity.

In men, the anima represents the unconscious feminine – the qualities of eros, relatedness, and receptivity that balance the masculine logos. When integrated, the anima can be a source of soulful depth and emotional intelligence, a conduit to the numinous realms of the psyche. But when neglected or projected, it can manifest as problematic femininity – as moodiness, irrationality, and a fear of commitment.

For von Franz, the key to transforming the animus and anima lay in the process of conscious dialogue and integration. By engaging with these inner figures – through active imagination, dream work, and creative expression – we can begin to differentiate them from our ego identities, recognizing them as autonomous parts of the psyche. We can learn to relate to them objectively, neither rejecting them as alien nor identifying with them completely.

This process of differentiation allows us to withdraw our projections from the outer world, releasing others from the burden of carrying our unconscious contents. We no longer seek the perfect partner to complete us but recognize the animus and anima as inner guides, allies in the journey of individuation. As we integrate their qualities into our conscious personality, we become more whole and androgynous, able to draw on both masculine and feminine strengths.

At the same time, von Franz emphasized that the animus and anima are not just personal archetypes but also collective ones. They reflect the cultural and historical patterns of gender that shape our society, the archetypal images of masculinity and femininity that we inherit from the collective unconscious. To fully integrate the animus and anima, we must also confront these collective patterns, challenging the stereotypes and inequalities that limit our experience of gender.

This is particularly important for women, who have long been oppressed by patriarchal structures that devalue the feminine. For von Franz, the liberation of the feminine required a radical re-visioning of the animus, a reclaiming of the positive masculine qualities that have been co-opted by the patriarchy. By developing a mature and integrated animus, women can find their own voice and authority, speaking truth to power and working for social change.

Ultimately, von Franz saw the integration of the animus and anima as essential for creating a more balanced and holistic world. In a culture that has long privileged the masculine over the feminine, the rational over the emotional, the individual over the relational, we need to reclaim the full spectrum of human qualities. We need to honor the feminine as well as the masculine, the heart as well as the head, the interconnectedness of all beings.

By doing this inner work of integrating the contra-sexual archetypes, we lay the foundation for a new kind of relationship – both with ourselves and with others. We move beyond the old dualisms and power dynamics, towards a more authentic and egalitarian way of being. We become more capable of true partnership, of sharing power and responsibility in service of the greater good.

Von Franz’s vision of the animus and anima thus has profound implications for our personal and collective lives. It challenges us to confront the ways in which we have internalized gender stereotypes and inequalities, and to work towards a more integrated and balanced expression of our humanity. It invites us to reclaim the lost parts of ourselves, and to honor the full diversity of human experience. And it calls us to create a world that values the feminine as well as the masculine, that seeks wholeness and connection rather than domination and division.

As we navigate the challenges of our time – the crises of climate change, social injustice, and spiritual disconnection – von Franz’s insights offer a path forward. By doing the inner work of integrating the animus and anima, we lay the foundation for a more balanced and sustainable world. We become more capable of the kind of creative collaboration and partnership that is needed to address the complex problems we face. And we tap into the transformative power of the feminine, the regenerative energies that can guide us towards a more hopeful future.

10. The Religious Function of the Psyche

Throughout her work, von Franz emphasized the religious function of the psyche – the innate human capacity for numinous experience and spiritual meaning. She saw this function as a fundamental aspect of the individuation process, a way of connecting with the transcendent dimensions of the Self and the greater mysteries of existence.

For von Franz, religion was not just a set of beliefs or practices but a living reality, an encounter with the sacred that transforms the individual from within. She distinguished between “creed-based” religions, which focus on doctrinal adherence and external authority, and “experience-based” spiritualities, which prioritize direct revelation and inner growth. While respecting the role of traditional religions, von Franz was more interested in the latter – in the personal and archetypal dimensions of the religious experience.

Drawing on Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious, von Franz saw the religious function as rooted in the archetypal realm – the timeless, universal patterns that structure the human psyche. She believed that all the world’s spiritual traditions were expressions of these archetypal realities, different “dialects” of the same primordial language of the soul.

In particular, von Franz was fascinated by the recurring motif of the “God-Man” – the divine being who takes on human form to bring salvation and transformation. Figures like Christ, Buddha, and Osiris represented the archetype of the Self in its numinous, world-redeeming aspect. By contemplating these images and stories, individuals could connect with the divine spark within themselves, the inner Christ or Buddha nature that guides the journey of individuation.

At the same time, von Franz warned against a literal or concretistic approach to religious symbols. She emphasized that the archetypes were not fixed or definitive but multivalent and contextual, taking on different meanings for different individuals and cultures. The task was not to worship the symbols themselves but to use them as portals to the numinous, as keys to unlock the deeper layers of the psyche.

For von Franz, this approach to religion required a kind of psychological fluidity – an ability to move between different spiritual frameworks and perspectives. She herself drew on a wide range of traditions in her work, from Christianity and Buddhism to alchemy and shamanism. She saw these as complementary paths to the same essential truth, different facets of the one diamond of the Self.

This ecumenical spirit was reflected in von Franz’s deep interest in esoteric and mystical traditions. She believed that these “inner” paths offered a more direct and experiential approach to the numinous, one that bypassed the dogmas and power structures of institutional religion. Practices like meditation, dream work, and active imagination provided a way of cultivating the religious function, of opening oneself to the transformative power of the sacred.

At the heart of von Franz’s vision was a profound trust in the wisdom and guidance of the psyche. She believed that the individuation process was ultimately a spiritual journey, a quest for meaning and purpose that leads beyond the ego to the greater reality of the Self. By aligning ourselves with this inner guide, we could navigate the challenges of life with greater clarity and resilience, drawing on the regenerative power of the numinous.

For von Franz, this power was not just a personal resource but a collective one as well. In a time of global crisis and upheaval, she believed that the religious function had a vital role to play in the transformation of human consciousness. By reconnecting with the archetypal dimensions of the sacred, we could tap into the creative energies that are needed to build a more just and sustainable world.

This is no easy task, of course. It requires a willingness to confront the shadows and distortions that have accumulated around religion, the ways in which it has been used to justify violence, oppression, and ignorance. It means grappling with the complex relationship between the archetypal and the historical, the universal and the particular. And it demands a deep humility, a recognition of the ultimate mystery and ineffability of the divine.

But if we can rise to this challenge, von Franz believed, we have the potential to create a new kind of spirituality – one that honors the full spectrum of human experience, from the personal to the cosmic, the psychological to the transpersonal. This spirituality would be grounded in the living reality of the psyche, the direct encounter with the numinous that transforms us from within. It would be pluralistic and inclusive, recognizing the many paths to the One. And it would be engaged with the world, working towards the collective healing and awakening that is our deepest purpose and calling.

In the end, von Franz’s vision of the religious function invites us to a radical re-enchantment of the world, a way of seeing the sacred in the midst of the everyday. It challenges us to cultivate a more intimate and experiential relationship with the divine, one that goes beyond belief to the immediacy of encounter. And it calls us to become agents of transformation, midwives of a new consciousness that can lead us through the darkness of our time to a more luminous future.

As we navigate the uncharted waters of the 21st century, von Franz’s insights offer a beacon of hope and guidance. By reclaiming the religious function of the psyche, we open ourselves to the numinous dimensions of existence, the mystery and wonder that pervade all things. We discover a source of meaning and resilience that can sustain us through the trials ahead, a wellspring of creativity and compassion that can help us forge a more beautiful world. And we take our place in the larger story of the universe, the great unfolding of spirit and matter that is the ground of our being and becoming.

May we have the courage and grace to heed this call, to trust in the wisdom of the psyche and the guidance of the Self. May we become the servants and stewards of the sacred, working to heal the rifts that divide us and to awaken the divinity that lies within. And may we remember, always, the great mystery that enfolds us, the love that moves the sun and the other stars.

Retrospective: The Legacy of Marie-Louise von Franz

The work of Marie-Louise von Franz represents a monumental contribution to the field of depth psychology, one that continues to inspire and challenge us today. As a close collaborator of Jung and a pioneering thinker in her own right, von Franz helped to expand the horizons of analytical psychology, bringing it into dialogue with a wide range of disciplines and traditions.

Perhaps her greatest legacy lies in her exploration of the objective psyche – the autonomous, archetypal dimensions of the unconscious that shape our inner and outer lives. Through her studies of fairy tales, alchemy, number symbolism, and synchronicity, von Franz illuminated the universal patterns and principles that structure the psyche, offering a map of the territory that lies beyond the ego.

In doing so, she helped to deepen and enrich Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious, showing how it manifests not only in dreams and myths but in the very fabric of reality itself. Her work on the archetypal meaning of numbers, for example, revealed a hidden order and intelligence in the cosmos, a meaningful patterning of psyche and matter that challenges our modern, disenchanted worldview.

Von Franz’s insights into the problem of evil and the inferior function also represent an important contribution to depth psychology. By exploring the shadow side of the psyche and the way it can possess individuals and groups, she shed light on the darker aspects of human nature and the need for a more integrated approach to morality and spirituality.

At the same time, von Franz’s emphasis on the transformative power of symbols and the religious function of the psyche offered a path forward, a way of engaging with the numinous dimensions of existence that can lead to healing and wholeness. Her vision of individuation as a spiritual journey, a quest for meaning and purpose that leads beyond the ego to the larger reality of the Self, continues to inspire seekers and practitioners around the world.

Of course, like any great thinker, von Franz was also a product of her time and place, shaped by the cultural and historical context in which she lived. Some of her ideas about gender and sexuality, for example, may seem dated or problematic from a contemporary perspective. Her focus on the animus and anima as contra-sexual archetypes, while groundbreaking in its day, has been critiqued by later scholars for reinforcing binary notions of gender and ignoring the diversity of human experience.

Similarly, von Franz’s emphasis on the objective and universal aspects of the psyche has been challenged by postmodern and constructivist thinkers, who argue that all knowledge is contextual and perspectival. From this view, the archetypes are not timeless and transcendent but culturally and historically situated, shaped by the language and beliefs of a particular time and place.

Despite these criticisms, however, there is no denying the enduring power and relevance of von Franz’s work. Her insights into the archetypal dimensions of the psyche, the transformative power of symbols, and the religious function of the soul continue to resonate with seekers and scholars alike. Her vision of a more enchanted and interconnected world, one that honors the sacred within and without, feels more urgent and necessary than ever in our time of global crisis and upheaval.

Ultimately, perhaps the greatest testament to von Franz’s legacy lies in the way her ideas have been taken up and developed by later thinkers in the field of depth psychology. James Hillman, in particular, was deeply influenced by von Franz’s work, even as he challenged and expanded many of her core concepts.

Like von Franz, Hillman emphasized the objective and archetypal dimensions of the psyche, arguing that the soul is not just a personal or subjective reality but a universal and cosmic one. He too was fascinated by the way symbols and images shape our inner and outer lives, and he sought to develop a “poetic basis of mind” that could honor the numinous and the imaginal.

At the same time, Hillman broke with von Franz in important ways. He rejected the idea of the Self as a unitary and transcendent entity, arguing instead for a “polytheistic” view of the psyche as a multiplicity of archetypal forces and figures. He also challenged the notion of individuation as a linear and teleological process, proposing a more open-ended and “deconstructive” approach to self-realization.

Perhaps most importantly, Hillman emphasized the political and cultural dimensions of the psyche, arguing that psychology must engage with the larger issues of our time. He saw the soul not just as an individual reality but as a collective one, shaped by the myths and values of the society in which we live. For Hillman, the task of depth psychology was not just to heal the individual but to transform the culture, to “make soul” in the world through a re-visioning of our fundamental beliefs and assumptions.

In this sense, Hillman represents both a continuation and a critique of von Franz’s legacy. He builds on her insights into the archetypal and objective dimensions of the psyche, even as he challenges some of her core assumptions and methods. He expands the scope of depth psychology to include the political and cultural realms, while still honoring the numinous and the imaginal.

As we look to the future of depth psychology, it is clear that the work of von Franz and Hillman will continue to play a vital role. Their insights into the archetypal dimensions of the psyche, the transformative power of symbols, and the religious function of the soul are more relevant than ever in our time of global crisis and upheaval. At the same time, their differences and debates remind us that the field is always evolving, always in dialogue with itself and with the larger world.

Ultimately, perhaps the greatest lesson we can take from von Franz and Hillman is the need for a depth psychology that is both deeply personal and profoundly engaged with the issues of our time. A psychology that honors the numinous and the imaginal, the archetypal and the objective, while still grappling with the complex realities of culture and politics. A psychology that seeks not just to heal the individual but to transform the world, to awaken the soul of humanity to its deepest purpose and potential.

As we navigate the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, may we be guided by the wisdom and vision of these great thinkers. May we have the courage to explore the depths of the psyche, to confront the shadows within and without, and to work towards a more just and sustainable world. And may we never lose sight of the great mystery that enfolds us, the love and beauty that is our birthright and our calling.

For in the end, as von Franz and Hillman both knew, the task of depth psychology is nothing less than the redemption of the world, the healing of the anima mundi, the soul of the world. It is a task that requires all of our creativity and compassion, all of our intelligence and imagination. But it is also a task that promises the greatest reward of all: a world that is more whole and holy, more enchanted and alive, more fully human and divine.

May we rise to this challenge with grace and grit, with humility and hope. May we become the ancestors that the future is dreaming of, the midwives of a new era that is longing to be born. And may we never forget the words of the poet Rilke, which capture the essence of the depth psychological vision:

“You must change your life.

Not out of arrogance or an illusion of moral superiority, which so often accompany a conversion,

But because a passion, glimpsed in its true intensity, will not let you remain who you were.”

So let us change our lives, and in so doing, change the world. Let us follow the passion of the soul, wherever it may lead us. And let us trust that, in the end, all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.

Bibliography

Abt, T. (2005). Introduction to Picture Interpretation According to C.G. Jung. Living Human Heritage Publications.

Bachelard, G. (1969). The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

Baring, A., & Cashford, J. (1991). The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image. Viking Arkana.

Barron, F., Montuori, A., & Barron, A. (1997). Creators on Creating: Awakening and Cultivating the Imaginative Mind. Penguin Putnam.

Bolen, J. S. (1984). Goddesses in Everywoman: Powerful Archetypes in Women’s Lives. Harper & Row.

Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Pantheon Books.

Campbell, J. (1974). The Mythic Image. Princeton University Press.

Corbin, H. (1998). The Voyage and the Messenger: Iran and Philosophy. North Atlantic Books.

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and Archetype. Penguin Books.

Edinger, E. F. (1985). Anatomy of the Psyche: Alchemical Symbolism in Psychotherapy. Open Court.

Eliade, M. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton University Press.

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s Search for Meaning. Beacon Press.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1964). The Process of Individuation. In C. G. Jung (Ed.), Man and His Symbols. Dell Publishing.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1974). Number and Time: Reflections Leading Toward a Unification of Depth Psychology and Physics. Northwestern University Press.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1980). Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology. Inner City Books.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1980). On Divination and Synchronicity: The Psychology of Meaningful Chance. Inner City Books.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1993). The Feminine in Fairy Tales. Shambhala Publications.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1995). Creation Myths. Shambhala Publications.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1995). Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales. Shambhala Publications.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1997). Archetypal Dimensions of the Psyche. Shambhala Publications.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1998). C.G. Jung: His Myth in Our Time. Inner City Books.

Franz, M.-L. von. (1999). Dreams. Shambhala Publications.

Franz, M.-L. von. (2000). The Problem of the Puer Aeternus. Inner City Books.

Franz, M.-L. von. (2001). Animus and Anima in Fairy Tales. Inner City Books.

Freud, S. (1930). Civilization and Its Discontents. W.W. Norton & Company.

Grof, S. (2012). Healing Our Deepest Wounds: The Holotropic Paradigm Shift. Stream of Experience Productions.

Gurdjieff, G. I. (1999). Life is Real Only Then, When ‘I Am’. Penguin Compass.

Hannah, B. (2001). Encounters with the Soul: Active Imagination as Developed by C.G. Jung. Daimon.

Hillman, J. (1960). Suicide and the Soul. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1967). Insearch: Psychology and Religion. Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1979). The Dream and the Underworld. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1983). Archetypal Psychology: A Brief Account. Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1989). A Blue Fire: Selected Writings by James Hillman. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1996). The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. Random House.

Hillman, J. (2004). Archetypal Psychology. Spring Publications.

Hollis, J. (2004). Mythologems: Incarnations of the Invisible World. Inner City Books.

Hollis, J. (2004). Swamplands of the Soul: New Life in Dismal Places. Inner City Books.

Hollis, J. (2008). What Matters Most: Living a More Considered Life. Gotham Books.

Jung, C. G. (1959). Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1960). The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1961). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Vintage Books.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and His Symbols. Dell Publishing.

Jung, C. G. (1968). Psychology and Alchemy. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1969). Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological Types. Princeton University Press.

Merton, T. (1960). The Wisdom of the Desert. New Directions.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the Soul: A Guide for Cultivating Depth and Sacredness in Everyday Life. HarperCollins.

Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Pantheon Books.

Otto, R. (1958). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford University Press.

Perera, S. B. (1981). Descent to the Goddess: A Way of Initiation for Women. Inner City Books.

Plotinus. (1956). The Enneads. Penguin Books.

Rilke, R. M. (1984). Letters to a Young Poet. Random House.

Singer, J. (1994). Boundaries of the Soul: The Practice of Jung’s Psychology. Anchor Books.

Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court.

Tarnas, R. (2006). Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. Viking.

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy. Shambhala Publications.

Woodman, M. (1985). The Pregnant Virgin: A Process of Psychological Transformation. Inner City Books.

Woodman, M., & Dickson, E. (1996). Dancing in the Flames: The Dark Goddess in the Transformation of Consciousness. Shambhala Publications.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

0 Comments