Challenging Freud and Pioneering Feminine Psychology

"The perfect normal person is rare in our civilization. There is no such thing as absolute normality within a complex culture. The tremendous psychological stresses and strains of present-day life fall too unevenly and too heavily to allow an even development." - **Karen Horney, The Neurotic Personality of Our Time**

1. Introduction: A Pioneering Voice in Psychoanalysis

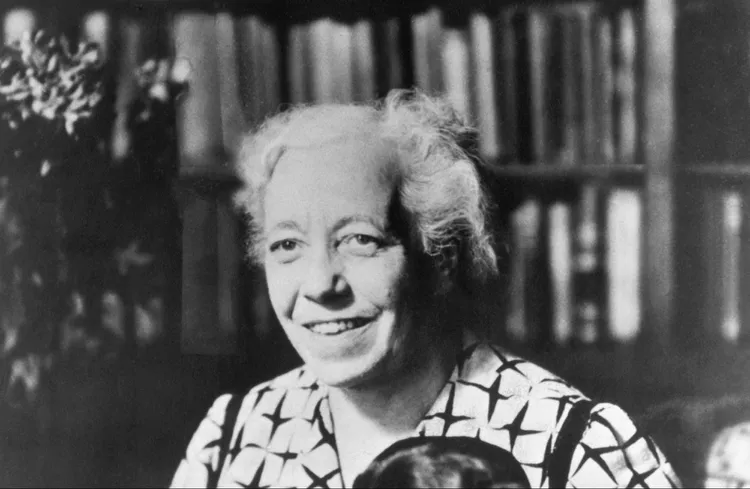

Karen Horney (1885-1952) stands as a towering, yet often underappreciated, figure in the history of psychology. She was a pioneering psychoanalyst whose contributions were instrumental in shifting the field’s focus from strict biological determinism to the profound **impact of culture and social relations** on the individual psyche. As one of the first influential female psychoanalysts, she not only provided foundational insights into neurosis and personality development but also directly challenged many of **Sigmund Freud’s central assumptions**, most notably his deterministic views on feminine psychology. Her insistence on a more holistic, humanistic approach to mental health, one that prioritized the inherent drive for **self-realization** over the repression of instinctual drives, fundamentally altered the trajectory of psychoanalytic thought and laid the groundwork for modern relational and feminist therapies. Horney’s work is what got me interested in psychoanalytic ideas when I started my practice, Taproot Therapy Collective in Alabama.

Born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1885, Horney’s early intellectual life was steeped in the Freudian tradition. She received her medical degree in 1913, an extraordinary accomplishment for a woman of her era, and was quickly embraced by the burgeoning Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute. However, even during her training and early practice, Horney began to detect critical flaws in the prevailing psychoanalytic orthodoxy. She grew increasingly dissatisfied with Freud’s **biological determinism**—the theory that instinctual, fixed drives (like the Oedipus complex and libido) governed behavior—especially when applied to women. Horney’s clinical observations suggested that psychological distress arose less from repressed sexual trauma and more from **disturbed human relationships** and the individual’s attempts to cope with a hostile, anxiety-provoking environment, a critical deviation from the established Viennese school.

Throughout her groundbreaking career, Horney meticulously developed a comprehensive, socio-cultural theory of personality. She posited that individuals develop deeply ingrained, patterned ways of relating to the world, which she termed **neurotic trends**, as a survival mechanism. These trends—the individual’s learned response to feelings of isolation, helplessness, and **basic anxiety** originating in childhood—are essentially maladaptive coping strategies. In Horney’s view, neurosis is a cultural disease, an understandable response to the intense competition, pervasive individualism, and familial neglect endemic in modern society. These defensive strategies tragically alienate individuals from their **real self**, obstructing their innate potential for growth, authenticity, and self-actualization. This cultural emphasis became the hallmark of what would later be termed **Neo-Freudian psychology**.

Horney’s intellectual impact solidified significantly following her emigration to the United States in 1932, a move prompted by the rise of Nazism and her growing ideological conflicts within the rigid German psychoanalytic community. She became a pivotal figure in American psychology, serving first at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis before moving to New York. Her dissent from orthodox Freudianism culminated in 1941 when she was expelled from the New York Psychoanalytic Institute. Unfazed, she co-founded the **Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis** and established the **American Institute for Psychoanalysis**, serving as its first Dean until her death. Her seminal works, including ***The Neurotic Personality of Our Time*** (1937), ***New Ways in Psychoanalysis*** (1939), and ***Our Inner Conflicts*** (1945), were uniquely accessible, reaching a wide popular audience and successfully demystifying complex psychoanalytic concepts for the general public.

Today, Horney is deservedly recognized as one of the most critical psychoanalytic thinkers of the 20th century. Her emphasis on the fluid, **socio-cultural determinants of mental health**, her courageous critique of Freudian orthodoxy, and her advocacy for a more **flexible, person-centered, and experiential approach to therapy** have all left an indelible mark on the field. Her foundational concepts—especially the innate drive toward the Real Self—continue to inspire and inform new generations of psychoanalysts, psychotherapists, and scholars who seek to understand the intricate and complex interplay of individual drive, interpersonal dynamics, and societal factors that profoundly shape the human experience.

2. Core Concepts and Key Ideas

Horney’s theoretical framework is characterized by its internal coherence and its consistent dedication to understanding how external stressors warp the internal world of the developing child and adult. Her concepts moved psychoanalysis away from the analytic couch’s focus on the distant past (infantile sexuality) toward the patient’s immediate, current relational world.

2.1. Basic Anxiety and the Need for Security

At the absolute heart of Horney’s comprehensive theory is the concept of **basic anxiety**. She defined this as a pervasive and profound feeling of insecurity, helplessness, and isolation that originates from the child’s perception of a hostile or indifferent social environment, primarily within the family unit. For Horney, basic anxiety is not just a symptom of neurosis—it is the **root cause** and the powerful driving force behind the development of all subsequent neurotic coping mechanisms or trends.

Horney firmly believed that children possess an **innate need for security, love, and genuine affection**. When these essential needs are not met adequately by the child’s primary caregivers—due to factors ranging from direct abuse and neglect to simple, but pervasive, inconsistency or coldness—the child develops overwhelming feelings of anxiety and a reactive hostility toward the world. These feelings are profoundly isolating, generating a deep sense of helplessness as the child feels utterly unable to rely on others for consistent support and fundamental protection. This existential insecurity becomes the wellspring of lifelong anxiety.

To survive this intolerable basic anxiety and escape the feeling of being utterly powerless in the world, Horney argued that the child develops various defensive maneuvers—the aforementioned “neurotic trends.” These strategies are rigid, compulsive attempts designed to alleviate internal feelings of insecurity and desperately manufacture a false sense of safety and control. Crucially, these trends become deeply ingrained and **compulsive** in the adult personality, rigidly shaping the individual’s approach to all relationships, their self-concept, and their overall engagement with life.

2.2. The Three Neurotic Trends

Horney synthesized the numerous relational coping styles she observed in her clinical practice into three fundamental “neurotic trends,” representing the characteristic ways individuals attempt to solve their basic anxiety by establishing some form of relation to others:

- **The compliant type (moving toward people):** This trend is characterized by a compulsive search for affection and approval as a primary means of coping with anxiety. Individuals exhibiting this trend present themselves as helpless, submissive, and excessively self-effacing in a desperate effort to avoid any conflict and maintain dependence in relationships. However, their superficial sweetness and compliant exterior often conceal deep, unexpressed feelings of **resentment and suppressed anger** stemming from their self-sacrificial posture. They live by the credo: “If I give in, I will not be hurt.”

- **The aggressive type (moving against people):** This trend involves seeking mastery and control over others as the solution to anxiety. Individuals adopt an aggressive stance, presenting themselves as strong, superior, and hyper-independent in order to mask their profound, underlying feelings of insecurity and vulnerability. Their behavior can range from overt hostility and intense competitiveness to more subtle, calculated forms of manipulation and exploitation designed to get their way. Their guiding principle is: “If I have power, no one can hurt me.”

- **The detached type (moving away from people):** This trend attempts to solve anxiety through emotional withdrawal and self-sufficiency. Individuals compulsively seek isolation, maintaining a careful emotional distance and presenting as aloof, self-sufficient, and entirely unaffected by the opinions or actions of others. Their apparent independence, however, rigidly masks deep feelings of **loneliness** and an intense **fear of intimacy**. Their unconscious motto is: “If I withdraw, nothing can touch me.”

Horney was careful to emphasize that these are not rigid, destiny-determining personality types, but rather **flexible, compulsive strategies**. Most individuals, she argued, exhibit some combination of all three trends, although usually one or two will become dominantly exaggerated, creating severe internal conflict. Neurosis is defined by the rigid, *compulsive* adherence to one of these strategies regardless of the actual situation, stifling genuine, spontaneous engagement with the world.

2.3. The Idealized Self and Self-Hatred

A cornerstone of Horney’s later work is the concept of the **idealized self**, the neurotic attempt to solve the internal conflict created by the compulsive trends. According to Horney, individuals who are unable to develop a secure and realistic sense of self-worth—the result of unassuaged basic anxiety—compensate by creating an exaggerated, idealized image of themselves. This idealized self is an **unrealistic and grandiose conception** of oneself as perfectly capable, omnipotent, and fundamentally superior to others. This process is known as the **search for glory**.

The construction of this idealized self, Horney argued, is a neurotic defense mechanism that allows the individual to escape their intolerable real self (full of self-doubt and feelings of inferiority) and temporarily live in a fantasy. By compulsively striving to live up to this unrealistic, fabricated ideal, the individual temporarily alleviates anxiety and feels a burst of narcissistic pride. However, this idealized self is an inevitable source of inner tension and profound conflict, as it sets **impossible standards** for the individual to meet and simultaneously alienates them from their true, authentic self, leading to an increasing split in the personality.

Crucially, Horney proposed that this drive toward the idealized self is invariably accompanied by intense feelings of **self-hatred and self-contempt**. As the individual inevitably fails to maintain the impossible fantasy of their idealized self (The Neurotic Claim), they experience intense feelings of shame, guilt, self-reproach, and worthlessness. This self-hatred—a “devastating inner foe”—is the driving force behind further neurotic symptoms, often manifesting as deep depression, pervasive anxiety, and a variety of self-sabotaging behaviors designed to punish the flawed, actual self.

2.4. The Tyranny of the Should

Directly related to the compensatory mechanism of the idealized self is Horney’s powerful and memorable concept: **the “tyranny of the should.”** She observed that neurotic individuals develop a rigid, utterly perfectionistic system of internalized demands and absolute standards—the “shoulds”—that they feel compulsively driven to live up to in order to achieve the fantasy of the idealized self and thus be worthy of love, respect, and admiration. These internalized “shoulds” can take the form of moral imperatives (“I should always be generous”), social expectations (“I should never fail or be emotional”), or impossibly high personal standards of excellence (“I should be the best at everything I attempt”).

The tyranny of the should, Horney argued, is a neurotic maneuver that provides a temporary illusion of complete control and a feeling of moral or personal superiority over others. By rigidly adhering to this self-imposed, strict code of conduct and constantly holding themselves to unattainable standards, the individual temporarily suppresses basic anxiety and feels a sense of righteousness. However, this rigid system is ultimately a profound source of chronic inner conflict and deep self-alienation. By constantly striving to satisfy an **external set of compulsive expectations**, the individual tragically loses touch with their own spontaneous, authentic desires, genuine values, and natural potential. The result is chronic dissatisfaction, pervasive guilt, deep fatigue, and often resentment, because they are structurally incapable of ever meeting their own relentless demands.

Furthermore, the tyranny of the should often results in a rigid, **moralistic approach to others**. The neurotic individual projects their own impossible standards onto those around them, becoming excessively critical, judgmental, and intolerant of others’ flaws, all while internally craving and needing their approval and validation to support their fragile idealized image.

2.5. The Real Self and Self-Realization

In sharp and optimistic contrast to the destructive, compulsive nature of the idealized self and the tyranny of the should, Horney posited the concept of the **Real Self**. The Real Self represents the **authentic, spontaneous, and creative core** of the individual, which is innately present from birth and possesses an inherent, self-directed drive to actualize its unique potentials. For Horney, the Real Self is the wellspring of all genuine, healthy psychological growth and development, guided by an **innate tendency toward self-realization and true fulfillment**—a concept that profoundly influenced later humanistic psychology, particularly Carl Rogers.

However, in neurotic individuals, this Real Self is tragically suppressed, distorted, or buried beneath the overwhelming demands of the idealized self and the crushing weight of the tyranny of the should. Cut off from their authentic desires, feelings, and inherent potentials, these individuals feel chronically anxious, empty, and deeply alienated from both themselves and others. This alienation is the core pathology Horney sought to address in therapy.

The central goal of psychoanalysis, in Horney’s re-envisioned framework, is to guide individuals back to reconnecting with their **Real Self** and to facilitate the development of a more authentic, spontaneous, and fulfilling way of being in the world. This is achieved through a deep exploration of the origins of the patient’s neurotic trends and defense mechanisms, enabling the patient to gain critical insight into the precise ways they departed from their true nature in childhood to adapt to an unfavorable environment.

Through the unique intimacy of the therapeutic relationship, individuals can experience a new, corrective sense of security, unconditional acceptance, and realistic self-worth. This allows them to gradually let go of the rigid neurotic defenses and to explore their authentic feelings, desires, and creative potentials without fear of catastrophe or self-hatred. By learning to truly trust and value their own inner experience, they develop a more realistic, compassionate, and flexible relationship with themselves and, consequently, with others.

Self-realization, in Horney’s view, is emphatically not a state of static perfection or a complete, utopian freedom from all anxiety. Instead, it is understood as a dynamic, **lifelong process of growth, discovery, and constant becoming**. It necessitates developing a more flexible and adaptive approach to life’s inevitable challenges, while simultaneously remaining courageously true to one’s core values and inherent potentials. This process demands a willingness to confront internal fears and external limitations, to embrace measured risks, and, most importantly, to cultivate a deep, foundational sense of **self-acceptance and self-compassion** in the face of imperfection.

3. Implications and Applications

3.1. Feminine Psychology and the Critique of Freud

One of Karen Horney’s single most significant and revolutionary contributions to the field was her comprehensive and devastating **critique of Freudian theories of feminine psychology**. She directly rejected Freud’s theory of **penis envy** and the Oedipus complex as the primary, immutable determinants of female development. Horney fundamentally argued that any psychological struggles women experienced arose predominantly from the **social and cultural devaluation of femininity** and the inherently limited opportunities provided by a patriarchal society for women to realize their full human potential. Her argument shifted the pathology from the woman’s body to the societal structure itself.

In her collected essays, ***Feminine Psychology*** (1922-1937), Horney boldly challenged Freud’s **phallocentric view** of sexuality and argued that women possess their own unique and valid developmental path, one shaped not merely by their biology but overwhelmingly by their social roles and cultural expectations. She theorized that women’s core psychology is characterized by a fundamental conflict between their powerful, innate desire for self-realization and the restrictive, pervasive demands of a patriarchal society that relentlessly pressures them toward passivity, submission, and often, neurotic self-sacrificing behavior. She also introduced the concept of **”womb envy,”** suggesting that male anxiety over the female capacity for biological creation was perhaps a deeper, more pervasive phenomenon than penis envy, which she viewed as merely a symbolic desire for the power and privilege afforded to men in society, not a biological deficit.

Horney insisted that many of the neurotic trends she observed in women—such as the compulsive need to be loved, the profound fear of appropriate assertiveness, and the tendency toward neurotic self-effacement—were not biological necessities but **direct consequences of this basic social conflict** and the restricted cultural avenues available for women to express their authentic potentials. She vigorously criticized Freud’s theory of the “masculinity complex” in women, re-framing it as an artifact of male **narcissism and projection**. Instead, she argued that a woman’s striving for independence, competence, and self-assertion is a perfectly healthy, necessary, and vital aspect of her natural human development, not a failed attempt at maleness.

Horney’s pioneering critique became a profound catalyst for the entire **feminist psychology movement** and subsequent waves of the women’s rights movement. Her powerful ideas challenged the foundational, often unseen patriarchal assumptions that underpinned traditional psychoanalysis and provided an essential framework for accurately understanding the measurable **psychological impact of gender oppression** on women’s lives. Her work successfully paved the way for a more nuanced, culturally-informed, and expansive approach to feminine psychology that finally recognized the inherent diversity and complexity of women’s experiences beyond biological caricature.

3.2. The Social and Cultural Determinants of Neurosis

A second, equally significant contribution of Horney’s work was her relentless emphasis on the **social and cultural determinants of neurosis**. This positioned her squarely as the founder of the Neo-Freudian school alongside Alfred Adler and Erich Fromm. She forcefully rejected Freud’s insistence on the primacy of biological and instinctual bases of psychological disturbance, arguing instead that neurosis is a direct outgrowth of **adverse social conditions** and the individual’s failed, compulsive attempts to adapt to a hostile, anxiety-provoking cultural environment. Neurosis was pathologized not in the individual’s libido, but in the cultural context.

In her landmark works, ***The Neurotic Personality of Our Time*** (1937) and ***Our Inner Conflicts*** (1945), Horney provided a rigorous analysis of the specific **psychological impact of modern industrial society** on human development. She meticulously argued that the extreme competitiveness, pervasive individualism (which she called the “philosophy of dogs eat dogs”), and emotional alienation inherent in contemporary culture conspire to create a generalized and crippling sense of **insecurity and basic anxiety** that fundamentally predisposes individuals to neurosis. Furthermore, she explored the precise mechanisms by which economic conditions, societal stratification, rigid social roles, and cultural expectations actively shape the development of specific neurotic trends and defense mechanisms.

Horney’s influential emphasis on the social determinants of neurosis had a demonstrable impact on the early development of **social psychiatry** and was instrumental in framing the study of mental health as a significant public health issue. Her ideas provided a compelling counterpoint to the deeply individualistic and often pathologizing tendencies of orthodox psychoanalysis. She created a vital framework for understanding the measurable ways in which social oppression, pervasive inequality, cultural dislocation, and poverty contribute directly to widespread psychological suffering. This focus established the idea that social reform could be a form of preventative mental health care.

Moreover, Horney’s systematic work clearly **anticipated many of the core insights** of contemporary cultural psychology and the study of the self in context. Her emphasis on the dynamic ways in which culture profoundly shapes both individual development and the construction of the self has influenced a wide and diverse range of theoretical perspectives, ranging from social constructionism and symbolic interactionism to modern narrative psychology, proving her model’s enduring relevance.

3.3. Self-Psychology and the Relational Turn

Karen Horney’s persistent emphasis on the central importance of the **Real Self** and the crucial relational context of psychological development proved highly significant for the emergence of both **self-psychology** and the later **relational turn** in psychoanalysis. Her conceptualization of the Real Self, the neurotic Idealized Self, and the indispensable role of the corrective therapeutic relationship in facilitating self-realization acted as a conceptual bridge, anticipating many of the central themes that would later be championed by these schools.

Later self-psychologists, such as **Heinz Kohut**, and relational theorists, such as **Stephen Mitchell**, built directly upon Horney’s relational sensitivity. They similarly emphasized the fundamental importance of empathic attunement, the therapeutic handling of transferences (or “self-object transferences,” as Kohut termed them), and the concept of the co-construction of meaning within the therapeutic process. These schools adopted Horney’s fundamental view of the self as being intrinsically **relational and intersubjective**, a fluid entity fundamentally shaped by early, formative interactions with caregivers and subsequent interpersonal experiences rather than by fixed, biological instincts.

Furthermore, Horney’s consistent emphasis on the intrinsic value of the **Real Self** and the fundamental, universal need for individuals to develop a more authentic, integrated, and self-directed way of engaging with the world strongly resonates with contemporary, evidence-based theories of authenticity, self-determination theory, and motivational interviewing. Her profound insights into the precise ways in which neurotic trends and rigid defense mechanisms actively interfere with natural self-realization and personal growth have had a demonstrable influence across a wide spectrum of therapeutic modalities, particularly within humanistic and existential approaches to psychotherapy.

3.4. Psychoanalytic Feminism and the Politics of Mental Health

Finally, Karen Horney’s foundational work has had an undeniable and lasting impact on the development of **psychoanalytic feminism** and the evolving **politics of mental health**. Her revolutionary critique of Freudian theories of femininity, combined with her steadfast emphasis on the pervasive social and cultural origins of neurosis, served as a core inspiration for generations of feminist scholars, clinicians, and activists. They sought to challenge the embedded patriarchal assumptions within traditional psychoanalysis and establish a more politically aware and socially engaged approach to mental health care.

Prominent psychoanalytic feminists who followed Horney, including **Nancy Chodorow**, **Jessica Benjamin**, and the philosophical work of **Judith Butler**, explicitly utilized and built upon Horney’s foundational insights. They expanded her focus to explore the complex ways in which gender, social power dynamics, intersectional identity, and culture shape the crucial development of the self and the construction of identity. Furthermore, they employed psychoanalytic concepts not merely for individual therapy but as powerful analytical tools to examine the societal ways in which social oppression, systemic trauma, and pervasive inequality contribute directly to widespread psychological suffering, thereby advocating for necessary social and political reform as a therapeutic act.

Moreover, Horney’s optimistic emphasis on the importance of **self-realization** and empowering personal growth profoundly influenced the emergence of modern **feminist therapy** and the broader women’s self-help movement of the late 20th century. Her ideas—that many women’s psychological struggles are fundamentally rooted in external social and cultural oppression, rather than internal biological defect—inspired feminist therapists to develop more empowering, contextualized, and politically engaged approaches to mental health care that specifically recognize and celebrate the inherent diversity and resilience of women’s experiences and strengths.

4. Critique and Limitations

While Karen Horney’s contributions to psychoanalysis and the understanding of personality theory are consistently recognized as significant and enduring, her theoretical framework is, as is true of all major theories, subject to various limitations and critiques. This section explores some of the main criticisms aimed at Horney’s ideas and considers how subsequent developments in psychoanalytic theory and research have attempted to refine and address these limitations.

4.1. Lack of Empirical Validation and Testability

One of the primary and most frequent criticisms leveled against Horney’s entire body of work is its fundamental **lack of empirical validation and testability**. Like many of her predecessors and contemporaries operating strictly within the early psychoanalytic tradition, Horney’s theories were constructed almost exclusively based on **detailed clinical observations** and rich, interpretive case studies, rather than on rigorous, systematic, and falsifiable empirical research. While her core ideas about the social and cultural etiology of neurosis and the innate human drive for self-realization possess undeniable intuitive appeal and clinical power, they have historically not been subjected to the stringent, standardized scientific testing required by contemporary psychology.

Furthermore, some of Horney’s most critical concepts, such as the qualitative distinctions between the three neurotic trends and the abstract, humanistic idea of the Real Self, prove notoriously difficult to reliably **operationalize and measure** using standardized, quantitative research methods. This inherent difficulty has made it extremely challenging for researchers to systematically assess the predictive validity, reliability, and broad generalizability of her theories across diverse populations and varying cultural contexts, leading to its categorization more as a clinical model than a scientific one.

4.2. Overgeneralization and Diagnostic Specificity

Another prominent criticism of Horney’s theoretical approach is that it tends toward **overgeneralization and lacks sufficient diagnostic specificity** in its broad characterization of human personality and psychological development. While Horney’s three neurotic trends—Moving Toward, Moving Against, and Moving Away—provide a clinically useful and parsimonious framework for understanding common patterns of coping with fundamental anxiety and insecurity, critics argue that they do not adequately capture the immense range, nuance, and complexity of human personality, particularly the spectrum of modern psychopathology defined by formal diagnostic manuals.

Moreover, Horney’s model is often criticized for failing to provide a clear, detailed **developmental account** of *how* and *when* these three neurotic trends emerge, consolidate, and specifically evolve over the lifespan. While she rightly emphasizes the paramount importance of early childhood experiences in shaping personality structure, she notably does not offer a detailed, fixed-stage model of psychosexual or psychosocial development comparable to those meticulously developed by Freud or Erik Erikson. The developmental mechanism remains underspecified.

Some critics have also argued that Horney’s central concept of the **Real Self** is perhaps too vague and difficult to define in a therapeutically precise or actionable manner. While she powerfully emphasizes the pursuit of authenticity and self-realization as the therapeutic goal, she does not provide clear, consistent criteria for empirically or clinically distinguishing the emergent Real Self from the often highly sophisticated **Idealized Self** or from those neurotic trends that may cleverly disguise themselves as genuine, healthy self-expression (e.g., neurotic self-sufficiency mistaken for autonomy).

4.3. Relative Neglect of the Unconscious and the Irrational

A key limitation often raised by orthodox Freudian scholars is that Horney’s revisionist work tends to **underestimate or neglect the potent, driving role of the unconscious and the irrational forces** in shaping human personality and behavior. While Horney does certainly acknowledge the importance of unconscious conflicts, defense mechanisms, and early fantasy, she consistently places a greater therapeutic emphasis on the role of conscious attitudes, current interpersonal relations, and observable coping strategies in shaping the adult personality and neurosis.

This deliberate, humanistic shift in emphasis has led some critics to argue that Horney’s comprehensive theory **underestimates the sheer, formative power** of deep unconscious drives, infantile fantasies, complex instinctual processes, and primal emotions in shaping the totality of human experience and behavior. While her emphasis on the social and cultural determinants of neurosis is demonstrably vital and highly relevant, critics suggest it may not fully account for the often powerfully **irrational, compulsive, and self-destructive tendencies** that frequently characterize profound psychological disturbance, which Freud attributed directly to id impulses.

4.4. Limited Attention to Diversity and Intersectionality

Finally, contemporary critics have raised valid concerns that Horney’s foundational work does not pay sufficient, systemic attention to the crucial issues of **diversity and intersectionality** within the matrix of human personality and psychological development. While she remains a towering figure for pioneering the critique of Freudian theories of femininity and emphasizing the vital social and cultural determinants of neurosis, her model does not adequately account for the intricate ways in which intersecting axes of identity—including **race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, disability status, and other social identities**—combine to profoundly shape the individual’s entire life experience and psychological well-being. Her cultural analysis, while pioneering, was still largely confined to the Western middle-class industrial context.

Moreover, some scholars have cautiously argued that Horney’s core concept of the **Real Self** and her deep therapeutic emphasis on the individual’s process of self-realization may unwittingly reflect a specific, **Western, liberal-individualistic bias**. This bias may fail to fully capture or respect the diverse ways in which the self is conceptualized, constructed, and experienced in profoundly different collectivist or non-Western cultural contexts. While her ethical ideas about the importance of empathy, mutuality, and authentic growth in the therapeutic relationship are universally valuable, they require careful adaptation and expansive interpretation to effectively address the unique needs and cultural realities of highly diverse clinical populations and global contexts.

5. Conclusion and Legacy

Despite the methodological and conceptual limitations raised by subsequent critiques, **Karen Horney’s contributions to the foundation of psychoanalysis and modern personality theory remain undeniably significant and enduring**. Her revolutionary insistence on the **social and cultural determinants of neurosis**, her courageous and transformative critique of Freudian theories of femininity, and her profound clinical insights into the human importance of self-realization and authentic personal growth have exerted a lasting and formative impact on the development of psychoanalytic theory, clinical practice, and the entire landscape of modern psychotherapy.

Horney’s visionary work has served as a direct inspiration for generations of scholars, relational therapists, and social justice activists who have consistently sought to challenge the rigid limitations of traditional, biologically focused approaches to mental health. They have developed more inclusive, ethically conscious, culturally-informed, and politically engaged approaches to understanding and effectively treating psychological suffering. Her enduring legacy serves as a powerful reminder of the necessity to attend to the complex, fluid interplay of individual development, interpersonal dynamics, and overarching societal factors that shape the unique human experience and the crucial need for a more holistic and compassionate approach to promoting psychological well-being and social justice.

As the field of psychoanalysis continues its necessary evolution, responding dynamically to new challenges and empirical insights, **Horney’s body of work remains a vital, living resource and an indispensable source of inspiration**. Her emphasis on the ethical importance of empathy, genuine mutuality, and promoting growth within the therapeutic relationship directly anticipated and informed many of the central themes that define contemporary relational and intersubjective approaches to psychotherapy. Furthermore, her foundational critique of the patriarchal assumptions embedded within traditional psychoanalysis and her steadfast emphasis on the social and cultural determination of psychological distress continue to actively inform both contemporary feminist and culturally-sensitive approaches to mental health care across the globe.

At the same time, Horney’s theoretical framework wisely reminds us of the ongoing, continuous need for rigorous theoretical refinement, intellectual elaboration, and continuous empirical testing. As modern clinicians and scholars build upon her powerful insights and seek to address the acknowledged limitations of her pioneering theory, the work demands a perpetual engagement with rigorous scientific research, precise clinical observation, and dynamic interdisciplinary dialogue. We must also remain acutely attuned to the vital contemporary issues of diversity, intersectionality, and cultural context, explicitly recognizing the complex, unique ways in which individual experience is meticulously shaped by a dense web of interlocking social, historical, and economic forces.

Ultimately, Horney’s legacy is defined by intellectual courage, profound compassion, and an unwavering commitment to human growth and flourishing. In a world that continues to be intensely complex, uncertain, and socially divided, her visionary model of a more authentic, deeply empathic, and socially engaged approach to understanding and alleviating human suffering remains as critically vital and relevant today as it was nearly a century ago. As we continue to grapple with the immense psychological and societal challenges of our time, we can draw profound inspiration and lasting theoretical guidance from her remarkable example, while always remaining intellectually open to new perspectives and possibilities for both individual and collective transformation.

Key Publications by Karen Horney

- The Neurotic Personality of Our Time (1937): Analysis of how modern culture generates anxiety and neurosis.

- New Ways in Psychoanalysis (1939): Direct and definitive rejection of Freudian instinct theory and determinism.

- Self-Analysis (1942): Guidance on applying psychoanalytic principles to one’s own inner life for personal growth.

- Our Inner Conflicts (1945): Detailed exploration of the neurotic dilemma and the core conflict between the three trends.

- Neurosis and Human Growth: The Struggle Toward Self-Realization (1950): Her final major work, emphasizing the drive toward the Real Self.

- Feminine Psychology (1922-1937, published posthumously): Critical essays refuting penis envy and exploring cultural causes of women’s distress.

- Final Lectures (1991, published posthumously): Insights into her evolving thought just before her death.

Further Reading and Authoritative Resources

Rubins, J. L. (1978). Karen Horney: Gentle rebel of psychoanalysis. New York: Dial Press. (Scholarly biography and intellectual history).

Paris, B. J. (1994). Karen Horney: A psychoanalyst’s search for self-understanding. New Haven: Yale University Press. (Definitive biographical and psychological analysis).

Quinn, S. (1987). A mind of her own: The life of Karen Horney. New York: Summit Books. (Comprehensive biographical study).

Westkott, M. (1986). The feminist legacy of Karen Horney. New Haven: Yale University Press. (Key work on her impact on feminist theory).

Katz, M. (1986). Karen Horney: 1885-1952. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143(6), 739-741. (Authoritative professional assessment).

The **American Institute for Psychoanalysis (AIP)**, founded by Karen Horney in 1941: https://aipnyc.org/

The **International Karen Horney Society (IKHS)**, dedicated to the study and promotion of her ideas: http://www.karenhorneysociety.org/

0 Comments