Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

In the 1990s, a peculiar trend emerged among car enthusiasts: transforming humble Honda Civics into pseudo-supercars by gluing on rocket fins, spoilers, and other garish modifications. The goal was to mimic the look of elite Ferraris and Lamborghinis without the matching performance. In many ways, this fad parallels the trajectory of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) in the world of psychotherapy.

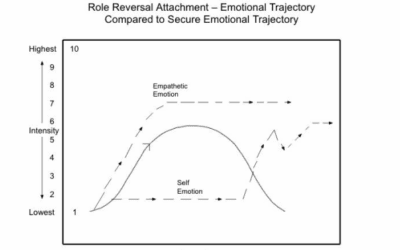

At its core, CBT is built on the practice of linking behaviors to emotions, and tracing those emotions back to the concious, cognitive, beliefs that CBT practitioners assert are the root cause of maladaptive behaviors. Where other models view trauma as coming from embodied and unconcious cognition, CBT sees it as only coming from language based, concious thought. While this works for simple things like biting nails or loosing weight, it might fail to work in places where patients have unconcious blindspots, biases and automatic assumptions about preconscious emotional reactions.

Developed by Aaron Beck, CBT aimed to strip away the theoretical digressions, extensive analysis, and conceptual explorations that were central to psychoanalytic and post-Freudian approaches. Beck argued that meaningful change could occur more efficiently through psychoeducation and behavioral interventions.

This “no frills” approach to therapy quickly gained favor with insurance companies and large healthcare organizations. CBT offered the allure of rapid results at lower costs compared to more traditional insight-oriented therapies. However, critics argue that in the process of streamlining, CBT has jettisoned the wisdom, intuition, and nuanced interpretations integral to neuroexperiential, and relational treatment modalities.

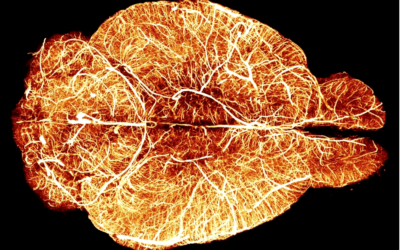

One significant shortcoming of CBT is its tendency to overlook the somatic roots of traumatized emotions. By focusing primarily on cognitive restructuring and behavioral modification, CBT often fails to address the subcortical brain regions where trauma is encoded and stored. Psychoeducation and intellectualization alone may not be sufficient to alter the underlying emotional reality of a client grappling with deep-seated trauma. CBT’s emphasis on measurable, externally observable changes can overshadow the importance of fostering emotional growth and self-insight, which many believe to be the key to lasting therapeutic progress.

In an effort to remain relevant and counter criticisms of its limitations, CBT has undergone endless modifications, spinning off countless specialized variants targeting specific populations and issues. Yet, these additions are often cosmetic, failing to fundamentally evolve the underlying assumptions and values of the approach. Much like slapping flashy accessories onto a standard Honda Civic and claiming it’s now a high-performance vehicle, these adaptations of CBT can sometimes come across as superficial attempts to address shortcomings without substantive change under the hood.

Ultimately, the debate surrounding CBT reflects a broader philosophical divide in the field of psychotherapy. On one side are those who prioritize measurable behavioral outcomes and view external, objective change as the primary goal of treatment. On the other side are those who emphasize the importance of emotional insight, self-understanding, and the subjective experience of the client as the foundation for meaningful and enduring transformation.

While CBT undoubtedly has its place in the therapeutic toolkit and has benefited many individuals, it’s important to recognize its limitations and the potential pitfalls of over-relying on a one-size-fits-all, manualized approach to the complex realm of mental health. As the field of psychotherapy continues to evolve, it may be time to look beyond the metaphorical rocket fins and critically examine the core principles guiding our interventions, striving for a more holistic and inclusive paradigm that addresses the multifaceted nature of the human psyche.

Here are 50 of the most popular rebrandings, specializations, and modifications of the CBT protocol starting with CBT itself.

Read More About Evidence Based Practice and Research Psychology:

Lessons from the STAR*D Scandal

The Corporatization of Healthcare

Incentives in Evidence Based Practice

Healing The Modern Soul Series Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Healing the Modern Soul Appendix

Time Line of Cognitive Therapy Development

1950s:

- Albert Ellis develops Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), one of the earliest forms of cognitive therapy.

1960s:

- Aaron Beck develops Cognitive Therapy (CT) for depression, which later evolves into Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

1970s:

- Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) is developed as a treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

- Cognitive Therapy is further refined and gains empirical support.

- Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) is developed by Thomas D’Zurilla and Arthur Nezu.

- Stress Inoculation Training (SIT) is developed by Donald Meichenbaum.

1980s:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy gains widespread recognition and acceptance.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is developed by Marsha Linehan for the treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

- Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) is developed by Patricia Resick for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- The concept of Behavioral Activation (BA) as a standalone treatment for depression emerges.

1990s:

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) is developed by Zindel Segal, Mark Williams, and John Teasdale for the prevention of depression relapse.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is developed by Steven Hayes and colleagues.

- Cognitive Behavioral Couple Therapy (CBCT) is developed by Donald Baucom, Norman Epstein, and colleagues.

- Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (IBCT) is developed by Andrew Christensen and Neil Jacobson.

- Schema Therapy (ST) is developed by Jeffrey Young.

- Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) is developed by James McCullough for the treatment of chronic depression.

- Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) is developed by Judith Cohen, Anthony Mannarino, and Esther Deblinger for children and adolescents with trauma.

2000s:

- Mindfulness-Integrated Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (MiCBT) is developed by Bruno Cayoun.

- Behavioral Sleep Medicine (BSM) gains recognition as a specialty area.

- Metacognitive Therapy (MCT) is developed by Adrian Wells.

- Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CCBT) and Internet-delivered CBT gain popularity.

- Transdiagnostic approaches, such as the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP), are developed.

- Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CA-CBT) gains attention.

2010s and beyond:

- Third-wave CBT approaches, such as ACT, DBT, and MBCT, continue to grow in popularity and evidence base.

- Specialized CBT protocols for specific disorders and populations are further developed and refined.

- Integrative approaches combining CBT with other therapeutic modalities gain traction.

- Technology-assisted CBT, such as mobile apps and virtual reality-based interventions, become more prevalent.

- Personalized and process-based CBT approaches are explored.

- Continued emphasis on dissemination, implementation, and cultural adaptation of CBT.

1. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) was developed by Aaron T. Beck in the 1960s. It is a short-term, goal-oriented psychotherapy treatment that focuses on changing patterns of thinking and behavior to improve mental health. CBT is based on the idea that thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are interconnected, and by changing one aspect, the others can be influenced.

Key publications and research studies:

- Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper & Row.

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press.

- Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 17-31.

CBT is effective in treating a wide range of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety disorders, phobias, and substance abuse. Patients seek CBT because it is a structured, time-limited approach that focuses on specific problems and goals. Providers like CBT because it is evidence-based, can be adapted to various settings, and has a strong emphasis on teaching patients practical skills to manage their symptoms.

2. Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) was developed by Patricia Resick and colleagues in the late 1980s as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). CPT is based on the idea that PTSD symptoms arise from conflicts between pre-existing beliefs and the traumatic event, leading to maladaptive coping strategies.

Key publications and research studies:

- Resick, P. A., & Schnicke, M. K. (1992). Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(5), 748-756.

- Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2016). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. New York: Guilford Press.

- Asmundson, G. J. G., Thorisdottir, A. S., Roden-Foreman, J. W., Baird, S. O., Witcraft, S. M., Stein, A. T., … & Powers, M. B. (2019). A meta-analytic review of cognitive processing therapy for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(1), 1-14.

CPT is primarily used to treat PTSD and related conditions. Patients seek CPT because it is a structured, time-limited approach that helps them process traumatic experiences and develop more adaptive beliefs and coping strategies. Providers like CPT because it has strong empirical support and can be delivered in individual or group settings.

3. Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) was developed by Judith Cohen, Anthony Mannarino, and Esther Deblinger in the 1990s. It is an evidence-based treatment for children and adolescents who have experienced trauma, as well as their non-offending caregivers.

Key publications and research studies:

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2017). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., & Steer, R. A. (2004). A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(4), 393-402.

- de Arellano, M. A., Lyman, D. R., Jobe-Shields, L., George, P., Dougherty, R. H., Daniels, A. S., … & Delphin-Rittmon, M. E. (2014). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65(5), 591-602.

TF-CBT is designed to help children and adolescents process traumatic experiences, manage trauma-related symptoms, and develop coping skills. Patients and their caregivers seek TF-CBT because it is a structured, short-term treatment that addresses both the child’s and the caregiver’s needs. Providers like TF-CBT because it has strong empirical support, can be adapted to various settings, and involves the child’s caregivers in the treatment process.

4. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) was developed by Marsha Linehan in the 1980s as a treatment for borderline personality disorder (BPD). DBT is based on the idea that BPD arises from a combination of emotional vulnerability and an invalidating environment, leading to difficulties in regulating emotions and behavior.

Key publications and research studies:

- Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

- Linehan, M. M., Armstrong, H. E., Suarez, A., Allmon, D., & Heard, H. L. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(12), 1060-1064.

- Stoffers, J. M., Völlm, B. A., Rücker, G., Timmer, A., Huband, N., & Lieb, K. (2012). Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (8), CD005652.

DBT is primarily used to treat BPD and related conditions, such as self-harm and suicidal behavior. Patients seek DBT because it focuses on teaching skills to regulate emotions, tolerate distress, and improve interpersonal relationships. Providers like DBT because it has strong empirical support and can be adapted to various settings, including individual therapy, group skills training, and phone coaching.

5. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT)

Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) was developed by Albert Ellis in the 1950s. It is based on the idea that emotional disturbances arise from irrational beliefs about events, rather than the events themselves.

Key publications and research studies:

- Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. New York: Lyle Stuart.

- Ellis, A., & Dryden, W. (1997). The practice of rational emotive behavior therapy (2nd ed.). New York: Springer Publishing.

- David, D., Cotet, C., Matu, S., Mogoase, C., & Stefan, S. (2018). 50 years of rational-emotive and cognitive-behavioral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 304-318.

REBT is used to treat a wide range of emotional and behavioral problems, including depression, anxiety, and anger. Patients seek REBT because it focuses on identifying and challenging irrational beliefs and developing more adaptive thinking patterns. Providers like REBT because it is a structured, active approach that emphasizes teaching patients practical skills to manage their emotions and behavior.

6. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) was developed by Steven Hayes and colleagues in the 1980s. ACT is based on the idea that psychological distress arises from attempts to avoid or control unwanted thoughts and feelings, rather than from the thoughts and feelings themselves.

Key publications and research studies:

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1-25.

- A-Tjak, J. G. L., Davis, M. L., Morina, N., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2015). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy for clinically relevant mental and physical health problems. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(1), 30-36.

ACT is used to treat a wide range of psychological problems, including depression, anxiety, chronic pain, and substance abuse. Patients seek ACT because it focuses on accepting difficult thoughts and feelings, clarifying personal values, and committing to values-consistent actions. Providers like ACT because it is a flexible, transdiagnostic approach that can be adapted to various settings and populations.

7. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) was developed by Zindel Segal, Mark Williams, and John Teasdale in the 1990s as a relapse prevention treatment for depression. MBCT combines elements of cognitive therapy with mindfulness practices derived from Buddhist meditation.

Key publications and research studies:

- Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press.

- Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., Ridgeway, V. A., Soulsby, J. M., & Lau, M. A. (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 615-623.

- Kuyken, W., Warren, F. C., Taylor, R. S., Whalley, B., Crane, C., Bondolfi, G., … & Dalgleish, T. (2016). Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: An individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(6), 565-574.

MBCT is primarily used to prevent relapse in individuals with a history of recurrent depression. Patients seek MBCT because it teaches them to relate differently to their thoughts and feelings, reducing the risk of relapse. Providers like MBCT because it has strong empirical support and can be delivered in a group format, making it a cost-effective intervention.

8. Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP)

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) was developed by Edna Foa and colleagues in the 1970s as a treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). ERP involves exposing patients to anxiety-provoking stimuli while preventing them from engaging in compulsive behaviors.

Key publications and research studies:

- Foa, E. B., & Kozak, M. J. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 20-35.

- Foa, E. B., Liebowitz, M. R., Kozak, M. J., Davies, S., Campeas, R., Franklin, M. E., … & Tu, X. (2005). Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(1), 151-161.

- Öst, L. G., Havnen, A., Hansen, B., & Kvale, G. (2015). Cognitive behavioral treatments of obsessive-compulsive disorder. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published 1993-2014. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 156-169.

ERP is primarily used to treat OCD and related conditions, such as hoarding disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Patients seek ERP because it helps them overcome their fears and reduce their compulsive behaviors. Providers like ERP because it has strong empirical support and can be delivered in individual or group settings.

9. Problem-Solving Therapy (PST)

Problem-Solving Therapy (PST) was developed by Thomas D’Zurilla and Arthur Nezu in the 1970s. PST is based on the idea that psychological distress often arises from ineffective problem-solving skills.

Key publications and research studies:

- D’Zurilla, T. J., & Nezu, A. M. (1999). Problem-solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

- Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2013). Problem-solving therapy: A treatment manual. New York: Springer.

- Cuijpers, P., de Wit, L., Kleiboer, A., Karyotaki, E., & Ebert, D. D. (2018). Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: An updated meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 48, 27-37.

PST is used to treat a wide range of psychological problems, including depression, anxiety, and stress-related disorders. Patients seek PST because it teaches them a structured approach to identifying and solving problems in their lives. Providers like PST because it is a practical, skill-based approach that can be adapted to various settings and populations.

10. Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP)

Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) was developed by James McCullough in the 1990s as a treatment for chronic depression. CBASP combines elements of cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal therapies.

Key publications and research studies:

- McCullough, J. P. (2000). Treatment for chronic depression: Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP). New York: Guilford Press.

- Keller, M. B., McCullough, J. P., Klein, D. N., Arnow, B., Dunner, D. L., Gelenberg, A. J., … & Zajecka, J. (2000). A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(20), 1462-1470.

- Negt, P., Brakemeier, E. L., Michalak, J., Winter, L., Bleich, S., & Kahl, K. G. (2016). The treatment of chronic depression with cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled clinical trials. Brain and Behavior, 6(8), e00486.

CBASP is primarily used to treat chronic depression, which is defined as depression that persists for at least two years. Patients seek CBASP because it addresses the interpersonal and cognitive factors that maintain chronic depression. Providers like CBASP because it has strong empirical support and is specifically designed for a challenging patient population.

11. Cognitive Behavioral Couple Therapy (CBCT)

Cognitive Behavioral Couple Therapy (CBCT) was developed by Donald Baucom, Norman Epstein, and colleagues in the 1990s. CBCT applies cognitive-behavioral principles to the treatment of relationship distress, focusing on modifying partners’ maladaptive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Key publications and research studies:

- Baucom, D. H., Epstein, N., Sayers, S., & Sher, T. G. (1989). The role of cognitions in marital relationships: Definitional, methodological, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(1), 31-38.

- Epstein, N. B., & Baucom, D. H. (2002). Enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy for couples: A contextual approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Fischer, M. S., Baucom, D. H., & Cohen, M. J. (2016). Cognitive-behavioral couple therapies: Review of the evidence for the treatment of relationship distress, psychopathology, and chronic health conditions. Family Process, 55(3), 423-442.

12. Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (IBCT)

Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (IBCT) was developed by Andrew Christensen and Neil Jacobson in the late 1990s. IBCT combines acceptance and change strategies to help couples improve their relationship satisfaction and functioning.

Key publications and research studies:

- Christensen, A., Jacobson, N. S., & Babcock, J. C. (1995). Integrative behavioral couple therapy. In N. S. Jacobson & A. S. Gurman (Eds.), Clinical handbook of couple therapy (pp. 31-64). New York: Guilford Press.

- Christensen, A., Atkins, D. C., Berns, S., Wheeler, J., Baucom, D. H., & Simpson, L. E. (2004). Traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy for significantly and chronically distressed married couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(2), 176-191.

- Roddy, M. K., Nowlan, K. M., Doss, B. D., & Christensen, A. (2016). Integrative behavioral couple therapy: Theoretical background, empirical research, and dissemination. Family Process, 55(3), 408-422.

13. Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy (CBGT)

Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy (CBGT) applies cognitive-behavioral principles in a group setting, allowing patients to learn from and support one another while developing coping skills and modifying maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

Key publications and research studies:

- White, J. R., & Freeman, A. S. (Eds.). (2000). Cognitive-behavioral group therapy: For specific problems and populations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bieling, P. J., McCabe, R. E., & Antony, M. M. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy in groups. New York: Guilford Press.

- Manassis, K., Mendlowitz, S. L., Scapillato, D., Avery, D., Fiksenbaum, L., Freire, M., … & Owens, M. (2002). Group and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(12), 1423-1430.

14. Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT)

Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) integrates cognitive-behavioral techniques with play therapy to help children express their thoughts and feelings, develop coping skills, and modify maladaptive behaviors.

Key publications and research studies:

- Knell, S. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral play therapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

- Knell, S. M., & Dasari, M. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral play therapy for children with anxiety and phobias. In A. A. Drewes (Ed.), Blending play therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy: Evidence-based and other effective treatments and techniques (pp. 3-21). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Pearson, Q. M. (2008). Role-play and case-based application of cognitive-behavioral play therapy. In C. E. Schaefer, S. Kelly-Zion, J. McCormick, & A. Ohnogi (Eds.), Play therapy for very young children (pp. 107-126). Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson.

15. Cognitive Behavioral Art Therapy (CBAT)

Cognitive Behavioral Art Therapy (CBAT) integrates cognitive-behavioral techniques with art therapy to help patients express their thoughts and feelings, develop coping skills, and modify maladaptive behaviors.

Key publications and research studies:

- Rosal, M. L. (2018). Cognitive-behavioral art therapy. New York: Routledge.

- Rosal, M. L. (1993). Comparative group art therapy research to evaluate changes in locus of control in behavior disordered children. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 20(3), 231-241.

- Sarid, O., & Huss, E. (2010). Trauma and acute stress disorder: A comparison between cognitive behavioral intervention and art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(1), 8-12.

16. Cognitive Behavioral Drama Therapy (CBDT)

Cognitive Behavioral Drama Therapy (CBDT) integrates cognitive-behavioral techniques with drama therapy to help patients express their thoughts and feelings, develop coping skills, and modify maladaptive behaviors.

Key publications and research studies:

- Blacker, J., Neuvonen, T., & Holmberg, N. (2017). Cognitive-behavioral drama therapy. In S. Brooke (Ed.), Combining the creative therapies with technology: Using social media and online counseling to treat clients (pp. 96-114). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

- Armstrong, C. R., Frydman, J. S., & Rowe, C. (2019). A snapshot of empirical drama therapy research: Conducting a general review of the literature. GMS Journal of Arts Therapies, 1, Doc04.

17. Behavioral Activation (BA)

Behavioral Activation (BA) is a standalone treatment for depression that focuses on increasing engagement in activities that promote positive reinforcement and improve mood.

Key publications and research studies:

- Martell, C. R., Addis, M. E., & Jacobson, N. S. (2001). Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Dimidjian, S., Hollon, S. D., Dobson, K. S., Schmaling, K. B., Kohlenberg, R. J., Addis, M. E., … & Jacobson, N. S. (2006). Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 658-670.

- Ekers, D., Webster, L., Van Straten, A., Cuijpers, P., Richards, D., & Gilbody, S. (2014). Behavioural activation for depression; an update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and sub group analysis. PloS one, 9(6), e100100.

18. Behavioral Sleep Medicine (BSM)

Behavioral Sleep Medicine (BSM) applies cognitive-behavioral principles to the treatment of sleep disorders, such as insomnia and circadian rhythm disorders.

Key publications and research studies:

- Perlis, M. L., Jungquist, C., Smith, M. T., & Posner, D. (2006). Cognitive behavioral treatment of insomnia: A session-by-session guide. New York: Springer.

- Edinger, J. D., & Carney, C. E. (2015). Overcoming insomnia: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mitchell, M. D., Gehrman, P., Perlis, M., & Umscheid, C. A. (2012). Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A systematic review. BMC Family Practice, 13, 40.

19. Behavioral Weight Loss (BWL)

Behavioral Weight Loss (BWL) applies cognitive-behavioral principles to the treatment of obesity and overweight, focusing on modifying eating and exercise habits.

Key publications and research studies:

- Wadden, T. A., & Stunkard, A. J. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of obesity treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

- Butryn, M. L., Webb, V., & Wadden, T. A. (2011). Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 34(4), 841-859.

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. (2002). Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(6), 393-403.

20. Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy for Chronic Depression (CBASP-CD)

Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy for Chronic Depression (CBASP-CD) is a specific application of CBASP tailored for the treatment of chronic depression.

Key publications and research studies:

- McCullough Jr, J. P. (2003). Treatment for chronic depression: Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP). Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 13(3-4), 241-263.

- Kocsis, J. H., Gelenberg, A. J., Rothbaum, B. O., Klein, D. N., Trivedi, M. H., Manber, R., … & Thase, M. E. (2009). Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy and brief supportive psychotherapy for augmentation of antidepressant nonresponse in chronic depression: The REVAMP trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(11), 1178-1188.

- Wiersma, J. E., Van Schaik, D. J., Hoogendorn, A. W., Dekker, J. J., Van, H. L., Schoevers, R. A., … & Van Oppen, P. (2014). The effectiveness of the cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy for chronic depression: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(5), 263-269.

21. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-E)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-E) is an adaptation of CBT specifically designed to treat eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder.

Key publications and research studies:

- Fairburn, C. G. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., O’Connor, M. E., Bohn, K., Hawker, D. M., … & Palmer, R. L. (2009). Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(3), 311-319.

- Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S., Doll, H. A., & Fairburn, C. G. (2013). Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: An alternative to family therapy? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(1), R9-R12.

21. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-E)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-E) is an adaptation of CBT specifically designed to treat eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder.

Key publications and research studies:

- Fairburn, C. G. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., O’Connor, M. E., Bohn, K., Hawker, D. M., … & Palmer, R. L. (2009). Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(3), 311-319.

- Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S., Doll, H. A., & Fairburn, C. G. (2013). Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: An alternative to family therapy? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(1), R9-R12.

22. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is a specific application of CBT designed to treat insomnia and other sleep disorders.

Key publications and research studies:

- Morin, C. M., & Espie, C. A. (2003). Insomnia: A clinical guide to assessment and treatment. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Edinger, J. D., Wohlgemuth, W. K., Radtke, R. A., Marsh, G. R., & Quillian, R. E. (2001). Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 285(14), 1856-1864.

- Trauer, J. M., Qian, M. Y., Doyle, J. S., Rajaratnam, S. M., & Cunnington, D. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(3), 191-204.

23. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis (CBT-P)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis (CBT-P) is an adaptation of CBT designed to treat psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, by modifying patients’ relationships with their psychotic experiences.

Key publications and research studies:

- Morrison, A. P., Renton, J. C., Dunn, H., Williams, S., & Bentall, R. P. (2003). Cognitive therapy for psychosis: A formulation-based approach. Hove, East Sussex: Brunner-Routledge.

- Wykes, T., Steel, C., Everitt, B., & Tarrier, N. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(3), 523-537.

- Morrison, A. P., Turkington, D., Pyle, M., Spencer, H., Brabban, A., Dunn, G., … & Hutton, P. (2014). Cognitive therapy for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders not taking antipsychotic drugs: A single-blind randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383(9926), 1395-1403.

24. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders (CBT-SUD)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Substance Use Disorders (CBT-SUD) applies cognitive-behavioral principles to the treatment of substance abuse and addiction.

Key publications and research studies:

- Beck, A. T., Wright, F. D., Newman, C. F., & Liese, B. S. (2011). Cognitive therapy of substance abuse. New York: Guilford Press.

- Carroll, K. M., & Onken, L. S. (2005). Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(8), 1452-1460.

- McHugh, R. K., Hearon, B. A., & Otto, M. W. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(3), 511-525.

25. Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT)

Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT) is a cognitive training intervention designed to improve cognitive functioning in patients with various mental health conditions, particularly schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Key publications and research studies:

- Wykes, T., & Reeder, C. (2005). Cognitive remediation therapy for schizophrenia: Theory and practice. London: Routledge.

- Wykes, T., Huddy, V., Cellard, C., McGurk, S. R., & Czobor, P. (2011). A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: Methodology and effect sizes. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(5), 472-485.

- Bowie, C. R., McGurk, S. R., Mausbach, B., Patterson, T. L., & Harvey, P. D. (2012). Combined cognitive remediation and functional skills training for schizophrenia: Effects on cognition, functional competence, and real-world behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(7), 710-718.

26. Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CCBT)

Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CCBT) delivers CBT interventions via computer programs or online platforms, increasing accessibility and flexibility for patients.

Key publications and research studies:

- Andrews, G., Cuijpers, P., Craske, M. G., McEvoy, P., & Titov, N. (2010). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. PloS one, 5(10), e13196.

- Hedman, E., Ljótsson, B., & Lindefors, N. (2012). Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: A systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 12(6), 745-764.

- Khanna, M. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(5), 737-745.

27. Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CA-CBT)

Culturally Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CA-CBT) modifies CBT interventions to better suit the cultural context and needs of patients from diverse backgrounds.

Key publications and research studies:

- Hinton, D. E., Rivera, E. I., Hofmann, S. G., Barlow, D. H., & Otto, M. W. (2012). Adapting CBT for traumatized refugees and ethnic minority patients: Examples from culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT). Transcultural Psychiatry, 49(2), 340-365.

- Naeem, F., Phiri, P., Nasar, A., Gerada, A., Munshi, T., Ayub, M., & Rathod, S. (2016). An evidence-based framework for cultural adaptation of cognitive behaviour therapy: Process, methodology and foci of adaptation. World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review, 11(1/2), 67-70.

- Rathod, S., Phiri, P., Harris, S., Underwood, C., Thagadur, M., Padmanabi, U., & Kingdon, D. (2013). Cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis can be adapted for minority ethnic groups: A randomised controlled trial. Schizophrenia Research, 143(2-3), 319-326.

28. Emotion-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (EF-CBT)

Emotion-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (EF-CBT) integrates emotion-focused techniques with traditional CBT to help patients better understand and manage their emotional experiences.

Key publications and research studies:

- Power, M. J. (2010). Emotion-focused cognitive therapy. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Power, M. J., & Dalgleish, T. (2015). Cognition and emotion: From order to disorder (3rd ed.). Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press.

- Timulak, L., & McElvaney, J. (2015). Emotion-focused therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: An overview of the model. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 45(1), 41-52.

29. Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-E)

Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-E) is an extension of CBT-E (see #21) that incorporates additional strategies and interventions to address a broader range of eating disorder psychopathology.

Key publications and research studies:

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2008). Enhanced cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders (“CBT-E”): An overview. In C. G. Fairburn (Ed.), Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders (pp. 23-34). New York: Guilford Press.

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., O’Connor, M. E., Palmer, R. L., & Dalle Grave, R. (2013). Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with anorexia nervosa: A UK-Italy study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(1), R2-R8.

- Byrne, S., Wade, T., Hay, P., Touyz, S., Fairburn, C. G., Treasure, J., … & Crosby, R. D. (2017). A randomised controlled trial of three psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 47(16), 2823-2833.

30. Family-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (FB-CBT)

Family-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (FB-CBT) integrates family therapy techniques with CBT to address mental health issues within the context of the family system.

Key publications and research studies:

- Barrett, P. M., Dadds, M. R., & Rapee, R. M. (1996). Family treatment of childhood anxiety: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 333-342.

- Wood, J. J., Piacentini, J. C., Southam-Gerow, M., Chu, B. C., & Sigman, M. (2006). Family cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(3), 314-321.

- Kendall, P. C., Hudson, J. L., Gosch, E., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Suveg, C. (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 282-297.

31. Guided Self-Help Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (GSH-CBT)

Guided Self-Help Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (GSH-CBT) provides patients with self-help materials (e.g., books, workbooks, online resources) and limited guidance from a therapist to work through CBT interventions independently.

Key publications and research studies:

- Cuijpers, P., Donker, T., van Straten, A., Li, J., & Andersson, G. (2010). Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychological Medicine, 40(12), 1943-1957.

- Hirai, M., & Clum, G. A. (2006). A meta-analytic study of self-help interventions for anxiety problems. Behavior Therapy, 37(2), 99-111.

- Newman, M. G., Erickson, T., Przeworski, A., & Dzus, E. (2003). Self-help and minimal-contact therapies for anxiety disorders: Is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(3), 251-274.

32. Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy (ICAT)

Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy (ICAT) combines cognitive, affective, and behavioral strategies to help patients with complex, comorbid mental health conditions.

Key publications and research studies:

- Wonderlich, S. A., Peterson, C. B., Smith, T. L., Klein, M. H., Mitchell, J. E., & Crow, S. J. (2015). Integrative cognitive-affective therapy for bulimia nervosa: A treatment manual. New York: Guilford Press.

- Peterson, C. B., Engel, S. G., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., Mitchell, J. E., Crow, S. J., … & Goldschmidt, A. B. (2020). Comparing integrative cognitive-affective therapy and guided self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy to treat binge-eating disorder using standard and naturalistic momentary outcome measures: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(9), 1418-1427.

- Wonderlich, S. A., Peterson, C. B., Crosby, R. D., Smith, T. L., Klein, M. H., Mitchell, J. E., & Crow, S. J. (2014). A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 44(3), 543-553.

33. Metacognitive Therapy (MCT)

Metacognitive Therapy (MCT) focuses on modifying patients’ metacognitive beliefs and processes, which are thought to maintain psychological distress.

Key publications and research studies:

- Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York: Guilford Press.

- Wells, A., & Matthews, G. (1996). Modelling cognition in emotional disorder: The S-REF model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(11-12), 881-888.

- Normann, N., van Emmerik, A. A., & Morina, N. (2014). The efficacy of metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Depression and Anxiety, 31(5), 402-411.

34. Mindfulness-Integrated Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (MiCBT)

Mindfulness-Integrated Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (MiCBT) incorporates mindfulness practices and principles into traditional CBT to help patients develop a more accepting and non-judgmental relationship with their thoughts and emotions.

Key publications and research studies:

- Cayoun, B. A. (2011). Mindfulness-integrated CBT: Principles and practice. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cayoun, B. A., Francis, S. E., Kasselis, N., & Skilbeck, C. (2012). Mindfulness-integrated cognitive behaviour therapy for the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder: A preliminary investigation. Clinical Psychologist, 16(2), 67-76.

- Cayoun, B. A., Simmons, A., & Shires, A. (2020). Immediate and lasting chronic pain reduction following a brief self-implemented mindfulness-based interoceptive exposure task: A pilot study. Mindfulness, 11(1), 112-124.

35. Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems (MATCH-ADTC)

The Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems (MATCH-ADTC) is a flexible, evidence-based treatment protocol that allows therapists to select and sequence CBT interventions based on the child’s specific needs and presenting problems.

Key publications and research studies:

- Chorpita, B. F., & Weisz, J. R. (2009). MATCH-ADTC:

36. Narrative Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (NCBT)

Narrative Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (NCBT) integrates narrative therapy techniques with CBT to help patients reframe their experiences and create more adaptive, empowering narratives.

Key publications and research studies:

- Gonçalves, M. M., Bento, T., Lopes, R. T., & Salgado, J. (2009). Manual for narrative-based cognitive therapy. Braga, Portugal: Universidade do Minho.

- Gonçalves, M. M., Ribeiro, A. P., Mendes, I., Matos, M., & Santos, A. (2011). Tracking novelties in psychotherapy process research: The innovative moments coding system. Psychotherapy Research, 21(5), 497-509.

- Lopes, R. T., Gonçalves, M. M., Machado, P. P., Sinai, D., Bento, T., & Salgado, J. (2014). Narrative therapy vs. cognitive behavioral therapy for moderate depression: Empirical evidence from a controlled clinical trial. Psychotherapy Research, 24(6), 662-674.

37. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT)

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is a family-centered treatment approach that combines play therapy and behavioral therapy techniques to improve the quality of the parent-child relationship and teach parents effective behavior management skills.

Key publications and research studies:

- Eyberg, S. M., & Funderburk, B. (2011). Parent-child interaction therapy protocol. Gainesville, FL: PCIT International.

- Lieneman, C. C., Brabson, L. A., Highlander, A., Wallace, N. M., & McNeil, C. B. (2017). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: Current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 239-256.

- Thomas, R., Abell, B., Webb, H. J., Avdagic, E., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2017). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 140(3), e20170352.

38. Positive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (P-CBT)

Positive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (P-CBT) integrates positive psychology interventions with traditional CBT to enhance well-being, resilience, and positive emotions in addition to addressing psychopathology.

Key publications and research studies:

- Bannink, F. P. (2012). Practicing positive CBT: From reducing distress to building success. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Geschwind, N., Arntz, A., Bannink, F., & Peeters, F. (2019). Positive cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of depression: A randomized order within-subject comparison with traditional cognitive behavior therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 119-130.

- Koeser, L., Dobbin, A., Pugh, J., Drummond, C., Patel, R., Banerjee, S., & McCrone, P. (2022). A randomised controlled trial of positive memory training, self-help CBT, and treatment-as-usual for depression in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 1-9.

39. Preventive Cognitive Therapy (PCT)

Preventive Cognitive Therapy (PCT) is a relapse prevention intervention for individuals with a history of recurrent depression, focusing on identifying and modifying negative thought patterns and developing coping strategies to prevent future episodes.

Key publications and research studies:

- Bockting, C. L. H., Schene, A. H., Spinhoven, P., Koeter, M. W. J., Wouters, L. F., Huyser, J., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2005). Preventing relapse/recurrence in recurrent depression with cognitive therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 647-657.

- Bockting, C. L. H., Smid, N. H., Koeter, M. W. J., Spinhoven, P., Beck, A. T., & Schene, A. H. (2015). Enduring effects of Preventive Cognitive Therapy in adults remitted from recurrent depression: A 10-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 185, 188-194.

- Biesheuvel-Leliefeld, K. E. M., Kok, G. D., Bockting, C. L. H., Cuijpers, P., Hollon, S. D., van Marwijk, H. W. J., & Smit, F. (2015). Effectiveness of psychological interventions in preventing recurrence of depressive disorder: Meta-analysis and meta-regression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 174, 400-410.

40. Rumination-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (RFCBT)

Rumination-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (RFCBT) is a treatment approach specifically designed to target rumination, a key maintaining factor in depression and anxiety.

Key publications and research studies:

- Watkins, E. R. (2016). Rumination-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. New York: Guilford Press.

- Watkins, E. R., Mullan, E., Wingrove, J., Rimes, K., Steiner, H., Bathurst, N., … & Scott, J. (2011). Rumination-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy for residual depression: Phase II randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(4), 317-322.

- Jacobs, R. H., Watkins, E. R., Peters, A. T., Feldhaus, C. G., Barba, A., Carbray, J., & Langenecker, S. A. (2016). Targeting ruminative thinking in adolescents at risk for depressive relapse: Rumination-focused cognitive behavior therapy in a pilot randomized controlled trial with resting state fMRI. PloS One, 11(11), e0163952.

41. Schema Therapy (ST)

Schema Therapy (ST) is an integrative treatment approach that combines elements of cognitive, behavioral, and experiential therapies to help patients identify and modify maladaptive schemas and coping styles.

Key publications and research studies:

- Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Press.

- Giesen-Bloo, J., van Dyck, R., Spinhoven, P., van Tilburg, W., Dirksen, C., van Asselt, T., … & Arntz, A. (2006). Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(6), 649-658.

- Masley, S. A., Gillanders, D. T., Simpson, S. G., & Taylor, M. A. (2012). A systematic review of the evidence base for schema therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 41(3), 185-202.

42. Stress Inoculation Training (SIT)

Stress Inoculation Training (SIT) is a cognitive-behavioral intervention designed to help individuals cope with stress and anxiety by teaching them a variety of coping skills and strategies.

Key publications and research studies:

- Meichenbaum, D. (2017). Stress inoculation training: A preventative and treatment approach. In The Evolution of Cognitive Behavior Therapy (pp. 117-140). Routledge.

- Saunders, T., Driskell, J. E., Johnston, J. H., & Salas, E. (1996). The effect of stress inoculation training on anxiety and performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(2), 170-186.

- Serino, S., Triberti, S., Villani, D., Cipresso, P., Gaggioli, A., & Riva, G. (2014). Toward a validation of cyber-interventions for stress disorders based on stress inoculation training: A systematic review. Virtual Reality, 18(1), 73-87.

43. Transdiagnostic Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (T-CBT)

Transdiagnostic Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (T-CBT) is an approach that targets common underlying mechanisms across multiple mental health conditions, rather than focusing on disorder-specific interventions.

Key publications and research studies:

- Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K., Boisseau, C. L., Allen, L. B., & May, J. T. E. (2010). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

- Norton, P. J., & Barrera, T. L. (2012). Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specific CBT for anxiety disorders: A preliminary randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Depression and Anxiety, 29(10), 874-882.

- Newby, J. M., McKinnon, A., Kuyken, W., Gilbody, S., & Dalgleish, T. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of transdiagnostic psychological treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 91-110.

44. Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Child Traumatic Grief (TF-CBT CTG)

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Child Traumatic Grief (TF-CBT CTG) is an adaptation of TF-CBT specifically designed to help children and adolescents who have experienced traumatic grief.

Key publications and research studies:

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2017). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Greenberg, T., Padlo, S., & Shipley, C. (2002). Childhood traumatic grief: Concepts and controversies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 3(4), 307-327.

- Grassetti, S. N., Williamson, A. A., Herres, J., Kobak, R., Layne, C. M., Kaplow, J. B., & Pynoos, R. S. (2018). Evaluating referral, screening, and assessment procedures for middle school trauma/grief-focused treatment groups. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(1), 10-20.

45. Trial-Based Cognitive Therapy (TBCT)

Trial-Based Cognitive Therapy (TBCT) is a variant of CBT that uses a mock trial format to help patients challenge and modify their maladaptive beliefs.

Key publications and research studies:

- de Oliveira, I. R. (2015). Trial-based cognitive therapy: A manual for clinicians. New York: Routledge.

- de Oliveira, I. R., Hemmany, C., Powell, V. B., Bonfim, T. D., Duran, É. P., Novais, N., … & Cesnik, J. A. (2012). Trial-based cognitive therapy versus cognitive therapy for depression: A protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 175.

- de Oliveira, I. R., Powell, V. B., Wenzel, A., Caldas, M., Seixas, C., Almeida, C., … & de Oliveira Moraes, R. (2012). Efficacy of the trial-based thought record, a new cognitive therapy strategy designed to change core beliefs, in social phobia. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 37(3), 328-334.

46. Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP)

The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP) is a transdiagnostic CBT approach that targets common core processes underlying various emotional disorders.

Key publications and research studies:

- Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Sauer-Zavala, S., Latin, H. M., Ellard, K. K., Bullis, J. R., … & Cassiello-Robbins, C. (2017). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

- Bullis, J. R., Fortune, M. R., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). A preliminary investigation of the long-term outcome of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(8), 1920-1927.

- Sakiris, N., & Berle, D. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Unified Protocol as a transdiagnostic emotion regulation based intervention. Clinical Psychology Review, 72, 101751.

47. Value-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (VB-CBT)

Value-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (VB-CBT) integrates values clarification and committed action from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) with traditional CBT techniques to help patients align their behaviors with their personal values.

Key publications and research studies:

- Ruiz, F. J., Luciano, C., Flórez, C. L., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., & Cardona-Betancourt, V. (2020). A multiple-baseline evaluation of a brief acceptance and commitment therapy protocol focused on repetitive negative thinking for moderate emotional disorders. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 16, 1-14.

- Tamannaeifar, S., Gharraee, B., Birashk, B., & Habibi, M. (2014). A comparative effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy and group cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 16(10), 60-63.

- Zargar, F., Farid, A. A. A., Atef-Vahid, M. K., Afshar, H., & Omidi, A. (2013). Comparing the effectiveness of acceptance-based behavior therapy and applied relaxation on acceptance of internal experiences, engagement in valued actions and quality of life in generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 18(2), 118-122.

48. Virtual Reality Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (VR-CBT)

Virtual Reality Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (VR-CBT) incorporates virtual reality technology into CBT to provide immersive, realistic exposure experiences and skill-building opportunities.

Key publications and research studies:

- Freeman, D., Reeve, S., Robinson, A., Ehlers, A., Clark, D., Spanlang, B., & Slater, M. (2017). Virtual reality in the assessment, understanding, and treatment of mental health disorders. Psychological Medicine, 47(14), 2393-2400.

- Valmaggia, L. R., Latif, L., Kempton, M. J., & Rus-Calafell, M. (2016). Virtual reality in the psychological treatment for mental health problems: An systematic review of recent evidence. Psychiatry Research, 236, 189-195.

- Bouchard, S., Dumoulin, S., Robillard, G., Guitard, T., Klinger, E., Forget, H., … & Roucaut, F. X. (2017). Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A three-arm randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(4), 276-283.

49. Web-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (WB-CBT)

Web-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (WB-CBT) delivers CBT interventions via the internet, providing a convenient, accessible, and cost-effective alternative to traditional face-to-face therapy.

Key publications and research studies:

- Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., Titov, N., & Lindefors, N. (2019). Internet interventions for adults with anxiety and mood disorders:

50. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in Primary Care (CBT-PC)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in Primary Care (CBT-PC) is a streamlined, evidence-based CBT protocol designed for use in primary care settings, where patients often present with a range of mental health concerns.

Key publications and research studies:

- Craske, M. G., Roy-Byrne, P. P., Stein, M. B., Sullivan, G., Sherbourne, C., & Bystritsky, A. (2009). Treatment for anxiety disorders: Efficacy to effectiveness to implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(11), 931-937.

- Roy-Byrne, P., Craske, M. G., Sullivan, G., Rose, R. D., Edlund, M. J., Lang, A. J., … & Stein, M. B. (2010). Delivery of evidence-based treatment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 303(19), 1921-1928.

- Muntingh, A. D., van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., van Marwijk, H. W., Spinhoven, P., & van Balkom, A. J. (2016). Collaborative care for anxiety disorders in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Family Practice, 17, 62.

0 Comments