How Therapy Can Heal Toxic Relationships

Leaving a toxic relationship is one of the bravest and most difficult steps a person can take. Whether it was a romantic partner, a family member, or a close friend, extricating yourself from a relationship pattern that was destructive to your well-being is a profound act of self-love and self-preservation.

However, the journey of healing doesn’t end the moment you walk away. In many ways, that’s just the beginning. The aftermath of a toxic relationship can leave you feeling shattered, confused, and deeply unsure of yourself. You may struggle with residual feelings of shame, self-doubt, and a pervasive sense of “not-enoughness.”

This is because toxic relationships, especially those that involve narcissistic abuse, have a way of eroding your very sense of self. When you’ve been subjected to constant criticism, gaslighting, and emotional manipulation, it’s easy to lose touch with who you are at your core. You may have learned to silence your own needs, to doubt your perceptions, and to contort yourself to please the other person.

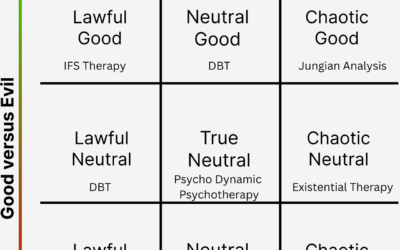

So how do you begin to recover from this profound level of soul-wounding? How do you reconnect with your authentic self and rebuild a life that feels true to you? While there is no single path to healing, various therapeutic approaches offer valuable insights and tools for this journey of reclamation.

The Jungian Perspective: Reclaiming the Disowned Self

From a Jungian or depth psychological perspective, the experience of being in a toxic relationship can be understood as a profound disconnection from one’s true self. According to Carl Jung, we all have a “shadow” – the parts of ourselves that we have rejected, denied, or disowned, often because they were not acceptable to our family or society (Zweig & Abrams, 1991).

In a toxic relationship, we may have learned to repress even more of ourselves in order to survive. We may have split off our vulnerability, our anger, our creativity, our sexuality – any part that was deemed “too much” or “not enough” by the other person. As a result, we can end up feeling fragmented, empty, and deeply out of touch with our own soul.

The Jungian path to healing involves a process of shadow work – of courageously reclaiming the disowned parts of ourselves (Johnson, 1993). This is not about becoming perfect, but about becoming whole. It’s about learning to embrace all of who we are, light and dark, and integrating these parts into a more authentic, fully-expressed self.

Some key practices in Jungian shadow work include (Zweig & Abrams, 1991):

Dream analysis:

Paying attention to the symbols, figures, and emotions that emerge in our dreams, which often carry messages from the unconscious about disowned parts of ourselves.

Active imagination:

Engaging in a guided fantasy dialogue with different aspects of our psyche, such as our inner critic or our wounded child, to better understand and integrate them.

Creative expression:

Using art, writing, movement, or other creative modalities to give form and voice to buried feelings and experiences.

By engaging in this deep inner work, we can start to reclaim the vitality, authenticity, and wholeness that may have been lost in the toxic relationship. We can learn to love and accept ourselves, shadow and all, and to trust in our own inner wisdom and resources.

The Parts Work Perspective: Healing the Wounded Parts

From the perspective of parts work therapies like Internal Family Systems (IFS) and Voice Dialogue, we all have multiple “parts” or subpersonalities within our psyche (Schwartz, 1995). These parts often develop in childhood as a way to cope with difficult or overwhelming experiences.

In a toxic relationship, certain parts may take on extreme roles in an attempt to protect us from further wounding. For example, we may have a “pleaser” part that constantly seeks to appease the other person, a “critic” part that berates us for our perceived failings, or a “numbing” part that helps us disconnect from painful feelings.

While these parts have good intentions, their extreme behaviors can keep us stuck in patterns of self-abandonment and self-betrayal. The goal of parts work therapy is not to eliminate these parts, but to help them transform and integrate in a way that supports our overall well-being.

Some key steps in an IFS approach to healing from a toxic relationship might include (Schwartz, 1995):

- Identifying the protective parts that emerged in the relationship, and honoring their efforts to keep us safe.

- Developing a compassionate, curious relationship with these parts from the perspective of the “Self” – the wise, loving essence at our core.

- Unburdening the extreme roles and emotions these parts took on, often by revisiting and reprocessing the early experiences that shaped them.

- Helping the parts to trust the leadership of the Self and to take on more balanced, harmonious roles in the internal system.

Through this gentle, step-by-step process, we can start to heal the deep wounds that the toxic relationship may have inflicted on our different parts. We can learn to listen to and care for our own needs, to set healthy boundaries, and to relate to ourselves and others from a place of centered, self-honoring wholeness.

The Somatic Perspective: Releasing Trauma from the Body

Toxic relationships, especially those that involve any form of physical or sexual abuse, can leave a profound imprint on the body. Even if the abuse was not physical, chronic emotional stress and trauma can still manifest in a range of somatic symptoms, such as muscle tension, digestive issues, or autoimmune flare-ups (Van der Kolk, 2015).

From a somatic perspective, healing from a toxic relationship must involve a process of releasing this stored trauma from the body. This is not just about talking about the experiences, but about gently reconnecting with the felt sense of the body and allowing its innate wisdom and healing capacity to unfold.

Some key principles of somatic approaches like Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Somatic Experiencing include (Ogden & Fisher, 2015):

Moving slowly and gently, working with small increments of traumatic material at a time to avoid overwhelming the nervous system.

Pendulation:

Guiding attention back and forth between resource states (sensations of safety, groundedness, ease) and small amounts of traumatic activation, to support the natural discharge of survival energy.

Completion of survival responses:

Allowing the body to complete any thwarted defensive responses (like pushing away or running) in a safe, controlled way, which can help restore a sense of agency and empowerment.

By learning to listen to and befriend the body, we can start to unwind the deep patterns of constriction, dissociation, or hyperarousal that may have taken hold in the toxic relationship. We can cultivate a new sense of safety, vitality, and at-homeness in our own skin.

The Experiential Perspective: Transforming Through Direct Experience

Experiential therapies like Gestalt and Ericksonian hypnosis emphasize the transformative power of direct, here-and-now experience. Rather than just talking about the past, these approaches invite us to actively explore and experiment with new ways of being in the present moment.

In the context of healing from a toxic relationship, an experiential approach might involve:

Role-playing:

Enacting different roles or scenarios (like confronting the abuser or practicing self-assertion) to build new skills and confidence.

Empty chair work:

Engaging in an imaginal dialogue with the toxic person (or with different parts of the self) to express unspoken feelings, needs, and boundaries.

Guided imagery:

Using the power of imagination to rehearse new, more empowered responses to challenging situations.

By engaging in these experiential explorations, we can start to break out of old, limiting patterns and to embody new possibilities for ourselves. We can get a felt sense of what it’s like to stand in our truth, to honor our needs, and to relate to ourselves and others with respect and clarity.

The Existential Perspective: Finding Meaning in the Pain

Finally, existential therapy offers a compelling lens for finding meaning and purpose in the aftermath of a toxic relationship. Existential approaches emphasize that suffering is an inherent part of the human condition, and that we all must grapple with fundamental concerns like death, isolation, freedom, and meaninglessness (Yalom, 1980).

From this perspective, the pain of a toxic relationship can be seen as a kind of existential crisis – a shattering of our assumptive world that forces us to confront deep questions about who we are and what we value. While undoubtedly difficult, this crisis can also be an opportunity for profound growth and transformation.

Some key existential themes that may arise in the healing process include (Yalom, 1980):

Responsibility:

Recognizing that we are fundamentally free beings, responsible for our own choices and actions, even in the face of outside influences or constraints.

Authenticity:

Learning to live in accordance with our own values and truths, rather than conforming to external expectations or pressures.

Meaning-making:

Finding or creating a sense of purpose and significance in our lives, even in the midst of pain and uncertainty.

By grappling with these ultimate concerns, we can start to reclaim a sense of agency, integrity, and direction in our lives. We can learn to use our suffering as a catalyst for greater self-awareness, compassion, and commitment to living authentically.

Bibliography:

Johnson, R.A. (1993). Owning your own shadow: Understanding the dark side of the psyche. Harper San Francisco.

Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment. W.W. Norton & Company.

Schwartz, R.C. (1995). Internal family systems therapy. Guilford Press.

Van der Kolk, B. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Yalom, I.D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Zweig, C., & Abrams, J. (Eds.). (1991). Meeting the shadow: The hidden power of the dark side of human nature. J.P. Tarcher.

Tags: healing from narcissistic abuse, recovering from toxic relationships, reclaiming authenticity, shadow work and healing, parts work therapy, somatic trauma release, experiential therapy techniques, existential perspectives on suffering, post-traumatic growth, self-abandonment recovery, rebuilding self-trust, honoring your truth, embodied healing practices, soul-aligned living

0 Comments