How does Therapy Treat Fibromyalgia?

Fibromyalgia is a complex, chronic condition that affects millions of people worldwide, primarily women. It is characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, sleep disturbances, cognitive difficulties, and a range of other symptoms that can significantly impact quality of life (Clauw, 2014). The experience of living with fibromyalgia often feels like what Carl Jung (1967) called “the tension of opposites” – a condition that is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere, felt deeply yet often invisible to others.

The Neuroscience of Pain

Recent advances in neuroscience have revolutionized our understanding of chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia. The work of Antonio Damasio (2018) and others has highlighted the crucial role of the subcortical brain in processing and regulating pain signals. Fibromyalgia is thought to involve a sensitization of the central nervous system, leading to amplified pain perception and abnormal pain processing (Sluka & Clauw, 2016).

This altered pain processing exemplifies what philosopher Henri Bergson (1913) called “duration” – the lived experience of time as shaped by subjective states like pain and sensation, rather than objective clock time. For individuals with fibromyalgia, time itself can feel distorted, with pain and fatigue exerting a profound influence on the perception of minutes, hours, and days (Hellström et al., 2020).

Psychological Dimensions of Chronic Pain

The psychological impact of living with fibromyalgia cannot be overstated. As Jungian analyst James Hillman (1974) described, chronic illness often involves a profound process of “soul-making” – a transformation of the psyche through the crucible of suffering. This process frequently involves confronting what Jung (1959) termed “the shadow” – the difficult, painful aspects of the self that are often repressed or denied.

For many with fibromyalgia, this shadow work involves grappling with feelings of grief, anger, frustration, and despair as they navigate the losses and limitations imposed by chronic pain (Triñanes et al., 2014). Learning to face and integrate these challenging emotions is a crucial part of the healing journey (Alcaraz-Rojas, 2018).

The Role of Trauma and Memory

Trauma-informed perspectives are increasingly recognized as essential for understanding and treating fibromyalgia (Buskila et al., 2019). Many individuals with fibromyalgia have a history of physical, emotional, or sexual trauma, and the condition itself can be experienced as a form of ongoing traumatization due to the persistent nature of symptoms (Yavne et al., 2020).

The work of Pierre Janet (1925) on traumatic memory is particularly relevant here. Janet described how trauma can become encoded in the body as physical sensations and symptoms that carry unresolved emotional and psychological significance. For those with fibromyalgia, pain itself can serve as a form of embodied traumatic memory, perpetuating a cycle of distress and hyperarousal (Buskila et al., 2019).

Therapeutic Approaches

Given the complex, multifaceted nature of fibromyalgia, effective treatment often requires a multidisciplinary approach that addresses both physical and psychological aspects of the condition (Sarzi-Puttini et al., 2020). Somatic Experiencing, developed by Peter Levine (1997), is one approach that has shown promise in helping individuals with fibromyalgia develop greater body awareness and improve their capacity for self-regulation (Nijs et al., 2021).

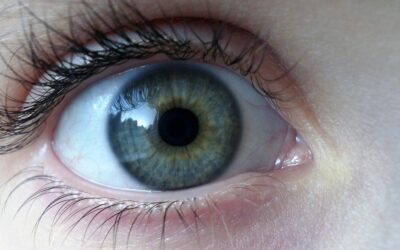

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is another valuable tool for addressing the trauma components that often underlie fibromyalgia symptoms (van der Kolk, 2014). By facilitating the processing and integration of traumatic memories, EMDR can help reduce pain perception and improve overall functioning (Lee & Kim, 2018).

Newer approaches like Brainspotting, developed by David Grand (2013), offer innovative ways of working with the neurophysiology of pain and emotion. By accessing eye positions associated with specific mental and emotional experiences, Brainspotting can help facilitate the release of stored trauma and promote healing on a deep, subcortical level (Grand, 2013).

Neurofeedback training has also emerged as a promising intervention for fibromyalgia, helping individuals develop better self-regulation of brain activity associated with pain processing and emotional distress (Goldway et al., 2019). By learning to modulate these brain patterns, individuals can gain a greater sense of control over their symptoms and improve overall well-being (Wu et al., 2020).

The Mind-Body Connection

Ultimately, understanding and treating fibromyalgia requires a holistic approach that honors the profound interconnections between mind and body. As psychotherapist Thomas Moore (2015) suggests, this involves a deep “care of the soul” – attending to both the physical symptoms and their psychological meanings with compassion and curiosity.

This perspective aligns with what Arnold Mindell (1985) termed “process-oriented psychology” – an approach that views symptoms not as problems to be eliminated, but as meaningful communications from the body that deserve to be heard and explored. By learning to listen to the wisdom of their bodies, individuals with fibromyalgia can develop a more collaborative, empowered relationship with their own healing process.

Cultural and Social Dimensions

The experience of fibromyalgia is deeply embedded within cultural and social contexts that shape how the condition is understood, diagnosed, and treated. As philosopher Michel Foucault (1973) analyzed, the complex relationships between illness, society, and power profoundly influence the ways in which certain conditions are legitimized or marginalized.

For those with fibromyalgia, navigating these social dynamics often involves what sociologist Erving Goffman (1963) called “stigma management” – the ongoing challenge of living with an invisible yet debilitating condition in a society that often privileges visible illness over more ambiguous, contested diagnoses. This stigma can compound the already significant burden of fibromyalgia, leading to feelings of isolation, invalidation, and self-doubt (Armentor, 2017).

Integration and Healing

Despite the many challenges of living with fibromyalgia, the journey towards healing and wholeness is possible. As mythologist Joseph Campbell (1949) described in his model of “the hero’s journey,” the path of transformation often involves a descent into the depths of suffering before a return to the world with newfound wisdom and strength.

For those with fibromyalgia, this journey often involves what Jungian analyst Marion Woodman (1998) termed “conscious femininity” – a process of reclaiming the body’s innate wisdom and developing a more nurturing, compassionate relationship with the self. By learning to honor the needs and rhythms of the body, individuals can cultivate a greater sense of agency and empowerment in the face of chronic illness.

Looking Forward

As our understanding of fibromyalgia continues to evolve, so too does our appreciation for the complexity and diversity of the human experience. Modern approaches to healing increasingly recognize what psychiatrist Stanislav Grof (2019) called “holotropic healing” – the importance of addressing all dimensions of the self, from the physical to the spiritual, in the pursuit of wholeness and well-being.

By embracing a truly integrative, person-centered approach to fibromyalgia care, we can begin to create a world in which all individuals, regardless of their health status or diagnosis, are empowered to live with dignity, purpose, and joy. May the journey towards healing continue to unfold, one brave step at a time.

To treat fibromyalgia or chronic pain conditions in Alabama, please contact Pamela Hayes at [email protected].

References

Alcaraz-Rojas, A. (2018). The lived experience of fibromyalgia: A phenomenological study. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 31(2), 139-159.

Armentor, J. L. (2017). Living with a contested, stigmatized illness: Experiences of managing relationships among women with fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 462-473.

Bergson, H. (1913). Time and free will: An essay on the immediate data of consciousness. George Allen & Unwin.

Buskila, D., Sarzi-Puttini, P., & Ablin, J. N. (2019). The genetics of fibromyalgia syndrome. Pharmacogenomics, 8(1), 67-74.

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. Pantheon Press.

Clauw, D. J. (2014). Fibromyalgia: A clinical review. JAMA, 311(15), 1547-1555.

Damasio, A. (2018). The strange order of things: Life, feeling, and the making of cultures. Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1973). The birth of the clinic: An archaeology of medical perception. Tavistock Publications.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall.

Goldway, N., Ablin, J., Lubin, O., Zamir, Y., Keynan, J. N., Or-Borichev, A., … & Hendler, T. (2019). Volitional limbic neuromodulation exerts a beneficial clinical effect on Fibromyalgia. NeuroImage, 186, 758-770.

Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: The revolutionary new therapy for rapid and effective change. Sounds True.

Grof, S. (2019). The way of the psychonaut: Encyclopedia for inner journeys. Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.

Hellström, C., Helin, U., & Sandström, S. (2020). “Like a wave that comes and goes”: A qualitative study about experiencing fibromyalgia over time. Musculoskeletal Care, 18(3), 326-334.

Hillman, J. (1974). Re-visioning psychology. Harper & Row.

Janet, P. (1925). Psychological healing: A historical and clinical study. George Allen & Unwin.

Jung, C. G. (1959). Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the self. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1967). Memories, dreams, reflections. Pantheon Books.

Lee, D. J., & Kim, J. H. (2018). The effect of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) on fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 111, 72-78.

Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the tiger: Healing trauma. North Atlantic Books.

Mindell, A. (1985). Working with the dreaming body. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Moore, T. (2015). Care of the soul: A guide for cultivating depth and sacredness in everyday life. Harper Perennial.

Nijs, J., De Kooning, M., & Ickmans, K. (2021). Somatic experiencing for patients with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(4), 804.

Sarzi-Puttini, P., Giorgi, V., Marotto, D., & Atzeni, F. (2020). Fibromyalgia: An update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 16(11), 645-660.

Sluka, K. A., & Clauw, D. J. (2016). Neurobiology of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. Neuroscience, 338, 114-129.

Triñanes, Y., González-Villar, A. J., Carrillo-de-la-Peña, M. T., & Romero-Yuste, S. (2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pain, 15(4), S17.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Woodman, M. (1998). Conscious femininity: Interviews with Marion Woodman. Inner City Books.

Wu, Y. L., Chang, L. Y., Lee, H. C., Fang, S. C., & Tsai, P. S. (2020). Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia: A meta-analysis of case-control studies. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 135, 110109.

Yavne, Y., Amital, D., Watad, A., Tiosano, S., & Amital, H. (2020). A systematic review of precipitating physical and psychological traumatic events in the development of fibromyalgia. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 50(2), 241-248.

Title: Understanding Pure OCD: Beyond the Visible Compulsions

0 Comments