Foucault’s Ideas for Understanding Power, Discourse and the Self

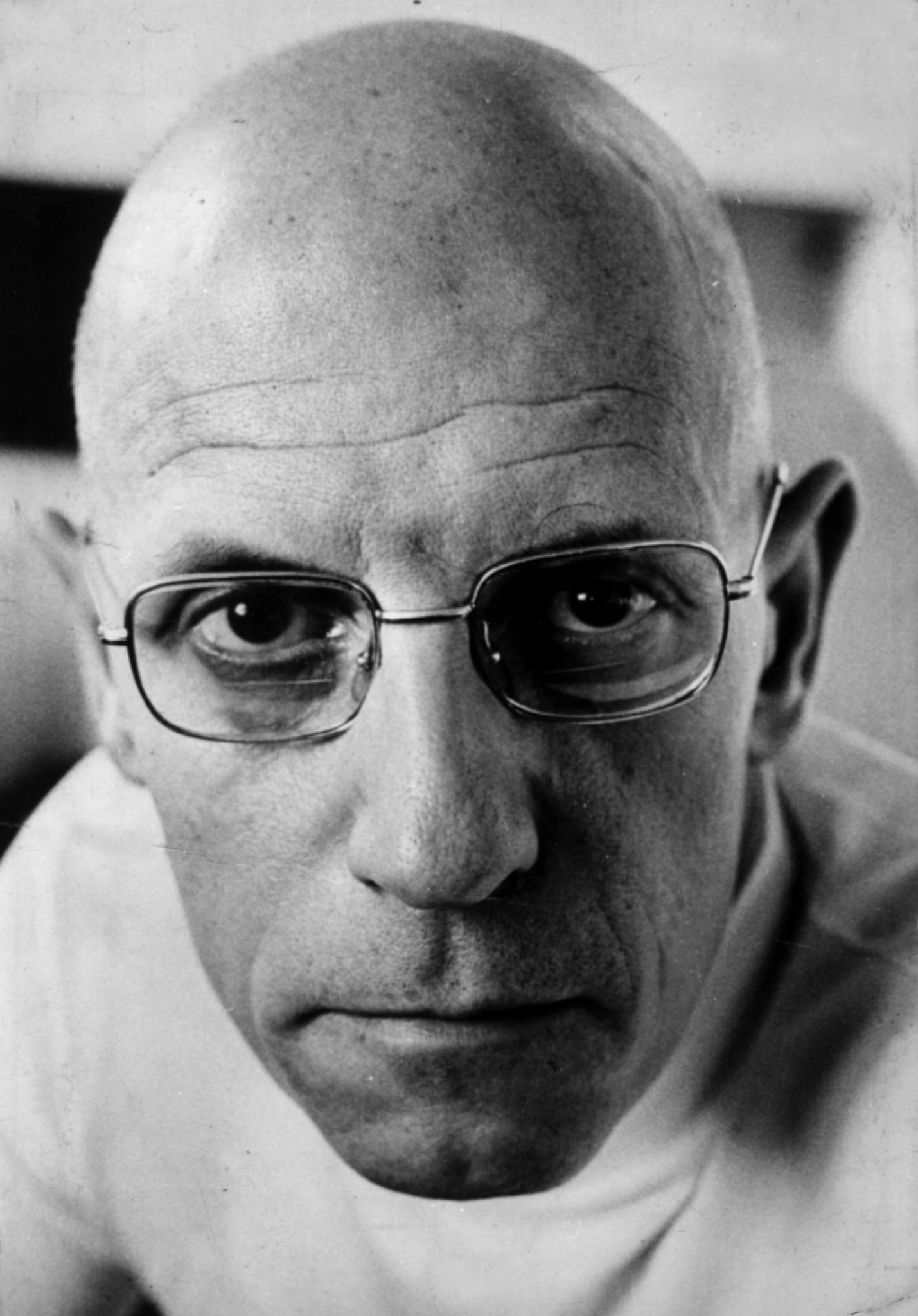

Who was Michel Foucault

Who was Michel Foucault

Who was Michel Foucault? Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was one of the most influential philosophers and social theorists of the 20th century. His groundbreaking ideas on power, knowledge, discourse, and the human subject have had a profound impact across disciplines like criminology, psychiatry, literary theory, and the history of sexuality.

Foucault’s Early Life and Career Born in Poitiers, France in 1926, Foucault studied philosophy and psychology at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris. After working as a cultural diplomat and teaching in Sweden, Poland, and Germany, he returned to France in the 1960s. He held positions at the University of Clermont-Ferrand and later the prestigious Collège de France.

His Early Works: Madness, Hospitals, and Disciplinary Power Foucault’s early works like Madness and Civilization (1961) and The Birth of the Clinic (1963) examined how modern institutions like asylums and hospitals emerged and shaped new forms of power and knowledge over the human subject.

In the 1970s, he shifted focus to analyzing disciplinary power and prisons in his famous 1975 work Discipline and Punish.

Key Points:

- Foucault (1926-1984) was an influential French philosopher and social theorist

- He examined how power, knowledge, and discourse shape human subjects and societies

- Key concepts include power/knowledge, discourse, biopower, governmentality, and technologies of the self

- Power produces knowledge and knowledge produces power in modern societies

- Discourses shape what is considered true or valid in different historical periods

- The human subject is not fixed, but constituted by various practices and discourses

- Foucault critiqued traditional views of power as top-down, seeing it as dispersed throughout society

- He explored how institutions like prisons, hospitals and schools exert disciplinary power

- Biopower refers to power over life itself and populations

- Governmentality describes the complex web of practices that govern individuals

- Foucault examined “technologies of the self” – ways individuals shape their own subjectivity

- His work has implications for understanding trauma, therapy, and social change

- He diverged from Freud and Jung by emphasizing the historical contingency of the self

- Some have misinterpreted his ideas to support neoliberal policies, overlooking his social justice aims

- Foucault’s analyses remain relevant for critiquing power and imagining new possibilities

Foucault’s Philosophy

Power/Knowledge

One of Foucault’s most influential concepts was “power/knowledge” – the idea that power produces knowledge, and knowledge produces power. Modern power operates by generating knowledge about individuals and populations to enable more effective control and normalization.

Discourse and Truth

Foucault was deeply interested in how language and discourse shape our understanding of truth and reality. He explored how each historical period is characterized by distinct “epistemes” or knowledge systems that determine what can be considered true.

Biopower and Governmentality

Later, Foucault developed the concepts of “biopower” (power over life and populations) and “governmentality” (the complex web of practices and institutions that govern individuals).

The Subject and Technologies of the Self

Foucault saw the human subject not as a fixed essence, but as constituted by various practices and discourses. He explored “technologies of the self” – ways individuals shape their own thoughts and behaviors.

Parrhesia and Courage of Truth

In his final lectures, Foucault examined the ancient Greek concept of parrhesia – the courage to speak truth to power. He saw this as a model for engaged intellectuals.

Trauma, Discourse and Subjectivity

While not directly addressing trauma, Foucault’s ideas have important implications for how we understand traumatic experiences. His work suggests trauma is shaped by social, cultural and historical contexts – the language used to describe it, the institutions responding to it, and how healing is constructed.

Trauma reflects the operation of power through discourse and representation, determining which forms of violence are recognized as traumatic and which are ignored or minimized.

Psychotherapy and Foucault

Foucault’s critique of the fixed, essential self challenges traditional therapy models aiming to uncover some innate true self. Instead, therapy should help develop new, empowering ways of relating to oneself beyond dominant discourses.

His work highlights the need to examine power dynamics within therapy itself, the cultural values shaping practice, and broader social forces contributing to experiences of trauma.

Potential existential therapeutic approaches inspired by Foucault include:

-

Examining how experiences are shaped by social narratives:

- Encouraging clients to question societal messages about what constitutes an “ideal” self, body, or life experience

- Analyzing how social structures and power dynamics shape one’s self-perception and desires

- Exploring how gender norms and expectations shape an individual’s sense of self-worth

Creating a more collaborative client-therapist relationship:

- Establishing an open dialogue about societal narratives that shape the client’s sense of self

- Empowering the client to question societal pressures and norms

- Involving the client in developing a treatment plan aligned with their values

Incorporating self-care practices to explore new subjectivities:

- Using mindfulness and self-compassion exercises to confront socialized stigmas

- Encouraging self-exploration of non-normative identities and desires

- Challenging expectations around gender norms, body image, and self-worth

Advocating for social changes to address oppressive systems:

- Active listening about how societal structures perpetuate injustices and self-stigma

- Promoting policies and initiatives that foster self-acceptance and inclusivity

- Challenging societal norms and stereotypes that contribute to self-stigma

In terms of the therapeutic process, this Foucaultian approach surfaces socialized narratives about the self, questions societal pressures, and encourages self-acceptance and growth. It aims to develop a healthier, more inclusive self-conception by rejecting rigid societal scripts.

Foucault, Freud and Jung on the Self While differing from Freud and Jung’s more universal models of selfhood, Foucault engages with questions of how individuals understand themselves.

For Freud, the self contained conflicting id, ego and superego components. Jung saw the self as the goal of integrating unconscious aspects of personality.

Foucault diverged by emphasizing the historical and cultural contingency of the self, constituted through discourses and practices rather than predetermined structures.

However, all three thinkers shared an interest in the role of language, power relations, and representation in shaping human experience and subjectivity.

Misunderstandings and Critiques Some neoliberal and conservative thinkers have tried to use Foucault’s critique of state power and emphasis on individual freedom to justify free-market policies and limited government.

However, such readings overlook Foucault’s subversive project aimed at social justice and transforming oppressive power relations, including his critique of how neoliberalism reduces individuals to human capital.

His skepticism of truth claims reflects a concern with how universal narratives can perpetuate domination, not a nihilistic rejection of all values.

Foucault’s innovative analyses transformed understandings of power, knowledge and subjectivity. While his complex ideas have sometimes faced misunderstandings, they remain vital resources for interrogating truth regimes and imagining new futures.

In an era of increasing surveillance and control, Foucault’s call for a “critical ontology of ourselves” – questioning the conditions that have made us who we are in order to remake ourselves anew – feels urgently needed.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Citations:

Foucault, M. (1961). Madness and Civilization. Random House.

Foucault, M. (1963). The Birth of the Clinic. Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1966). The Order of Things. Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1969). The Archaeology of Knowledge. Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and Punish. Random House.

Foucault, M. (1976). The History of Sexuality, Volume 1. Random House.

Further Reading:

Gutting, G. (Ed.). (2005). The Cambridge Companion to Foucault. Cambridge University Press.

Mills, S. (2003). Michel Foucault. Routledge.

Taylor, D. (Ed.). (2011). Michel Foucault: Key Concepts. Routledge.

Visker, R. (1995). Michel Foucault: Genealogy as Critique. Verso Books.

0 Comments