What Can the Origins of Religion Teach Us?

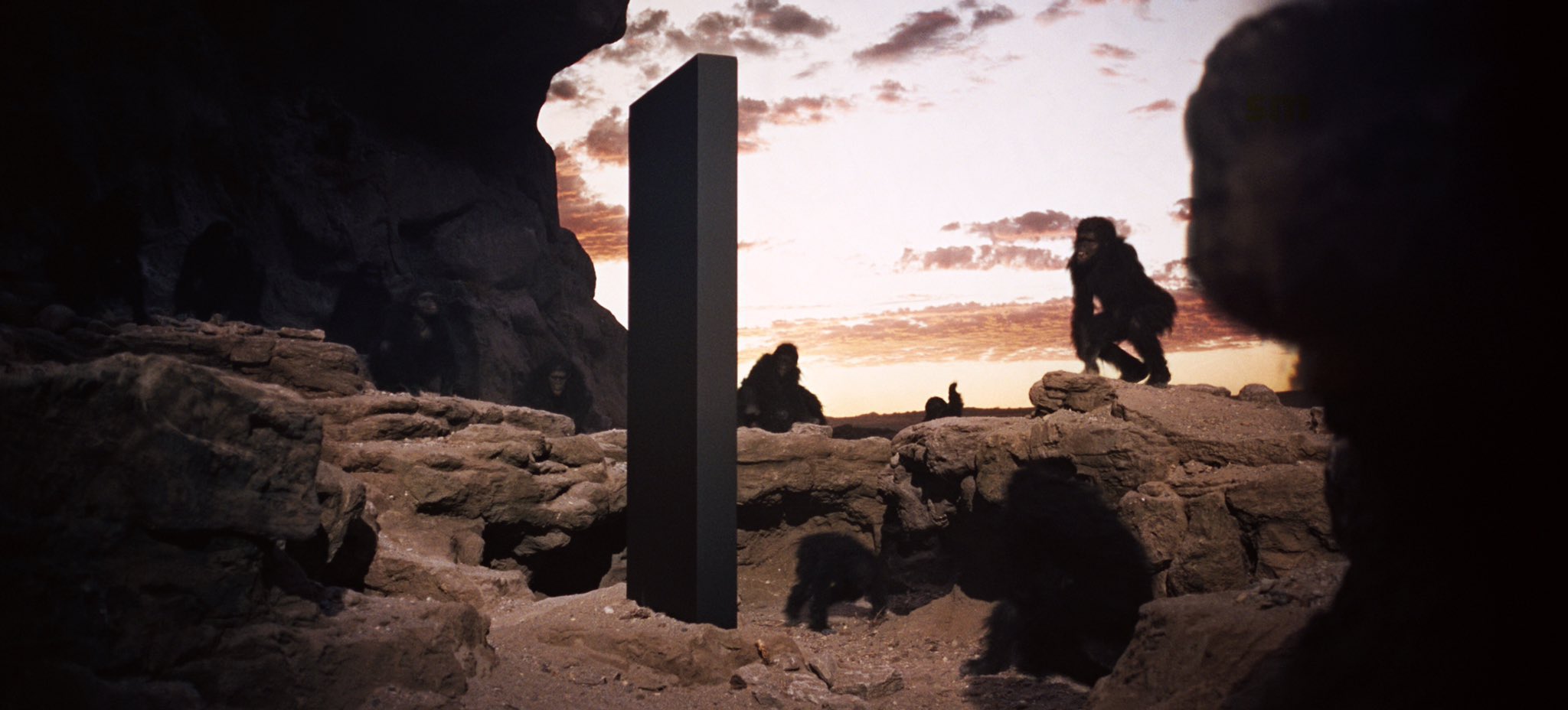

The origins and evolution of human religious like thought have long fascinated scholars, but they may also hold the keys to therapy and religion. . By examining the archaeological record, mythological narratives, and the insights of depth psychology, anthropology, evolutionary biology, and philosophy, we can begin to piece together a clearer picture of how prehistoric religions and pagan belief systems emerged and shaped the course of human culture.

The specialized and fragmented nature of modern psychology has led to an abstracted and decontextualized view of the self, one that is disconnected from the embodied, embedded, and enactive dimensions of human experience. By drawing upon the insights of anthropology, philosophy, and the study of ancient religious traditions, we can begin to re-imagine psychology as a more holistic and integrative discipline, one that recognizes the deep intertwining of mind, body, culture, and environment in shaping human experience and well-being.

In this re-imagined psychology, psychotherapists would function more like artists, shamans, or ritual healers, drawing upon the transformative power of symbol, metaphor, and embodied practice to facilitate healing and growth. By engaging with the mythic and archetypal dimensions of the psyche, and by fostering a deeper connection to the living world and the community of all beings, this new approach to psychology could help individuals and societies to navigate the challenges and mysteries of existence with greater wisdom, resilience, and creativity.

Alan Shore and the Neurobiology of Attachment

Alan Shore’s perspective on the sacred is rooted in the embodied, affective experiences of early childhood, particularly the preverbal emotional attunement between infants and their primary caregivers. For Shore, the foundation of our capacity to experience the sacred, to engage in symbolic thought, to empathize with others, and to develop self-awareness arises from the affective resonance and co-regulation that occurs between infants and their caregivers in the earliest stages of life.

This affective resonance creates a sense of being part of something larger than oneself, a feeling of deep connection and communion with another being. It is this primal experience of oneness and attunement that Shore sees as the basis for our later experiences of awe, wonder, and transcendence – the very qualities that define the sacred.

In Shore’s view, the self is not a pre-existing entity that emerges fully formed, but rather is shaped and molded through the intersubjective matrix of early affective experiences. The self arises out of the dynamic interplay of affective co-regulation between infant and caregiver, a process that lays the groundwork for the development of neural pathways involved in emotional regulation, stress response, and social bonding.

Ritual, in this context, can be understood as a way of rekindling and revisiting those primal experiences of affective attunement and communion. Through the use of symbolic gestures, vocalizations, and rhythmic movements, rituals create a shared affective state among participants, one that mimics the early experiences of co-regulation between infant and caregiver.

By engaging in rituals, whether they are religious ceremonies, communal celebrations, or even the simple rituals of daily life, we tap into those deep-seated memories of affective resonance and attunement, and experience a sense of connection and belonging that goes beyond our individual selves.

Integrating this understanding of the sacred into the practice of psychotherapy has profound implications. It suggests that the focus of therapy should not be solely on cognitive or behavioral interventions, but rather on the affective and non-verbal dimensions of communication and interaction.

By creating a sense of safety, trust, and “affective holding” within the therapeutic relationship, therapists can help clients to revisit and heal early experiences of trauma or disrupted attachment, and to restore a sense of secure attachment and emotional regulation.

This approach to therapy emphasizes the importance of the therapist’s own affective attunement and sensitivity, as well as their ability to create a space of emotional resonance and co-regulation with their clients. It also suggests that the use of non-verbal, embodied interventions such as music, art, or movement therapy may be particularly effective in accessing and working with the preverbal, affective dimensions of experience.

What sets Shore’s perspective apart from other thinkers is his grounding of spirituality and the sacred in the concrete, embodied realities of developmental neuroscience and attachment theory. Rather than seeing spirituality as a later cultural add-on or a product of abstract beliefs or concepts, Shore locates the origins of the sacred in the physical, visceral experiences of early bonding and attunement.

This implies that spirituality is not something separate from or added onto the self, but rather is inherent to the very formation and development of the self. The capacity for numinous experience, for awe and wonder, is woven into the fabric of our being from the earliest moments of life, shaped by the affective exchanges and co-regulatory processes that occur between infants and their caregivers.

From this perspective, prehistoric religion and spirituality would have emerged naturally and spontaneously from those embodied, affective experiences of social bonding and attunement. Rather than being a product of abstract thought or symbolic representation, the earliest forms of religion would have been rooted in the physical, sensory experiences of communal life – the shared rhythms of dance and song, the collective effervescence of ritual and celebration, the powerful experiences of oneness and interconnection that arise from affective resonance and co-regulation.

For contemporary psychotherapy, Shore’s perspective offers a powerful reminder of the importance of attending to the embodied, affective dimensions of human experience. It suggests that the path to healing and wholeness may not lie solely in the realm of cognitive insight or behavioral change, but rather in the nurturing of deep, affective connections and the cultivation of experiences of awe, wonder, and transcendence.

By creating a therapeutic space that allows for the safe exploration of primal affective states, and by using interventions that tap into the embodied, non-verbal dimensions of experience, therapists can help clients to reconnect with those early experiences of attunement and co-regulation, and to find a renewed sense of connection to themselves, to others, and to the sacred dimensions of life.

Ultimately, Shore’s perspective challenges us to see spirituality not as a separate domain of human experience, but as a fundamental aspect of our very being, rooted in the embodied, affective experiences that shape us from the earliest moments of life. By recognizing the deep interconnections between neurobiology, attachment, and the sacred, we can develop a more integrated, holistic approach to psychotherapy, one that honors the full complexity and richness of the human experience.

Louise Barrett and the Evolution of Social Cognition

Louise Barrett’s perspective on the origins of symbolic and religious thought is grounded in the evolution of social cognition – the ability to understand and navigate complex social relationships and hierarchies. For Barrett, the capacity for symbolic thought and the creation of shared meaning through language, art, and ritual emerged as a byproduct of the social cognitive abilities that allowed early hominins to coordinate group activities, share information, and imagine hypothetical scenarios.

In this view, the self is not an isolated, autonomous entity, but rather is fundamentally social and intersubjective, shaped by the web of relationships and interactions in which it is embedded. The very concept of selfhood, of an individual identity distinct from others, is a product of the evolution of social cognition, which allowed early humans to recognize themselves and others as separate beings with unique thoughts, feelings, and motivations.

The purpose of ritual, in Barrett’s perspective, is to bind groups together and attune individuals to each other’s minds and motives. By engaging in shared, symbolic activities such as dance, song, and storytelling, individuals create a sense of cohesion and commonality, reinforcing social bonds and facilitating cooperation and coordination.

Ritual also serves as a way of transmitting cultural knowledge and values across generations, creating a shared framework of meaning that allows individuals to make sense of their experiences and navigate the challenges of social life.

What sets Barrett’s perspective apart from other thinkers is her emphasis on the cognitive and evolutionary dimensions of religious thought and behavior. Rather than focusing solely on the affective or experiential aspects of spirituality, Barrett sees religion as emerging from the same cognitive capacities that underlie other forms of social cognition, such as language, theory of mind, and meta-representation.

This materialist, evolutionary grounding distinguishes Barrett’s approach from more abstract or metaphysical conceptions of religion, and highlights the ways in which religious thought and behavior are deeply intertwined with the practical, social functions of human cognition.

From this perspective, prehistoric rituals and religious practices would have been highly social and communicative in nature, serving to build and maintain social bonds, facilitate cooperation and coordination, and create shared imaginative worlds that allowed individuals to make sense of their experiences and navigate the challenges of group living.

These early forms of religion would have been less focused on abstract beliefs or doctrines, and more on the embodied, performative aspects of ritual and social interaction – the shared rhythms of dance and song, the collective storytelling and mythmaking, the public displays of commitment and loyalty to the group.

For contemporary psychotherapy, Barrett’s perspective offers a valuable lens through which to understand the social and interpersonal dimensions of selfhood and identity. By recognizing the ways in which our sense of self is shaped by our social relationships and interactions, therapists can help clients to develop a more nuanced and contextual understanding of their own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

This may involve exploring the social and cultural narratives that shape clients’ self-perceptions and worldviews, and helping them to identify and challenge limiting or maladaptive patterns of social cognition. It may also involve working with clients to build new social skills and strategies for navigating complex interpersonal dynamics, and to cultivate a greater sense of empathy, perspective-taking, and social attunement.

At a broader level, Barrett’s emphasis on the social functions of religion and ritual suggests that psychotherapy itself can be understood as a form of meaning-making and social bonding, one that helps individuals to create new narratives and frameworks for understanding their experiences and connecting with others.

By attending to the social and communicative dimensions of the therapeutic relationship, and by creating a safe and supportive space for the exploration of shared meaning and experience, therapists can help clients to develop a greater sense of belonging, purpose, and connection to the larger human community.

Ultimately, Barrett’s perspective challenges us to see the self not as an isolated, autonomous entity, but as a fundamentally social being, one whose very existence is predicated on the complex web of relationships and interactions that make up the fabric of human life. By recognizing the deep evolutionary roots of social cognition and symbolic thought, we can develop a more nuanced and integrated understanding of the ways in which religion, ritual, and meaning-making shape the human experience, and inform the practice of psychotherapy in the contemporary world.

Victor Turner and the Transformative Power of Ritual

Victor Turner’s concept of liminality is central to understanding his perspective on the nature of the sacred and the transformative power of ritual. For Turner, the liminal state is a critical component of ritual processes, one that allows individuals to step outside of their ordinary social roles and identities and enter into a fluid, ambiguous space of transition and possibility.

In the liminal phase of ritual, participants are stripped of their usual status and privileges, and are subject to a range of physical and psychological ordeals that break down their sense of self and identity. This process of “unmaking” is often accompanied by experiences of disorientation, vulnerability, and even terror, as individuals confront the dissolution of their familiar world and the emergence of new, unknown possibilities.

It is in this space of liminality, Turner argues, that individuals are most open to experiences of the sacred, as the boundaries between self and other, between the mundane and the transcendent, begin to dissolve. The sacred, in this view, is not a separate realm of experience, but is intimately bound up with the liminal state itself – the experience of being betwixt and between, of standing at the threshold of transformation and change.

The purpose of ritual, then, is to create a container for this transformative process, to provide a safe and structured space in which individuals can confront the challenges of the liminal state and emerge transformed and renewed. By guiding participants through the stages of separation, liminality, and reintegration, ritual facilitates a process of psychic and social transformation that allows individuals to shed old identities and ways of being, and to take on new roles and responsibilities within the community.

At a deeper level, Turner’s perspective suggests that the self is not a fixed or static entity, but is fluid and malleable, capable of undergoing profound transformations in the context of ritual and other liminal experiences. The self, in this view, is not so much a thing as a process – a constantly unfolding and evolving narrative that is shaped by the individual’s interactions with the social and symbolic worlds around them.

What sets Turner’s perspective apart from other thinkers is his emphasis on the transformative and creative power of the liminal state. While other perspectives may focus on the stabilizing or integrative functions of ritual, Turner sees ritual as a way of creating openings for change and transformation, both at the individual and collective levels.

This focus on the liminal makes ritual a more dynamic and unpredictable process, one that is less about reinforcing existing social structures and meanings, and more about creating spaces for the emergence of new forms of identity and social organization.

From this perspective, prehistoric rituals and religious practices may have been more transgressive and boundary-breaking than is often assumed, involving experiences of ecstatic states, altered consciousness, and the overturning of social norms and taboos. These early forms of religion would have been less focused on the maintenance of social order and stability, and more on the creation of transformative experiences that allowed individuals and communities to adapt to changing circumstances and forge new identities and ways of being.

For contemporary psychotherapy, Turner’s perspective offers a powerful framework for understanding the transformative potential of liminal experiences and states of consciousness. By recognizing the ways in which the self is shaped and transformed by encounters with the unknown and the unfamiliar, therapists can help clients to navigate the challenges of personal and social change, and to find meaning and purpose in the midst of uncertainty and flux.

This may involve creating therapeutic spaces that allow for the safe exploration of liminal states and experiences, such as through the use of expressive arts therapies, psychodrama, or other experiential approaches. It may also involve working with clients to develop new narratives and frameworks for understanding their experiences of change and transformation, and to integrate these experiences into a more flexible and adaptive sense of self.

At a broader level, Turner’s emphasis on the transformative power of ritual suggests that psychotherapy itself can be understood as a kind of liminal space – a container for the process of personal and social transformation that allows individuals to confront the challenges of growth and change in a safe and supportive environment.

By attending to the liminal dimensions of the therapeutic process, and by creating spaces for the emergence of new forms of identity and meaning, therapists can help clients to navigate the complexities of the human experience and to find a greater sense of wholeness, purpose, and connection in their lives.

Ultimately, Turner’s perspective challenges us to embrace the transformative potential of liminal experiences, and to see the self not as a fixed or static entity, but as a dynamic and evolving process that is shaped by our encounters with the unknown and the unfamiliar. By recognizing the sacred dimensions of these liminal spaces, and by creating containers for their exploration and integration, we can develop a more holistic and transformative approach to psychotherapy, one that honors the fluid and ever-changing nature of the self and the world around us.

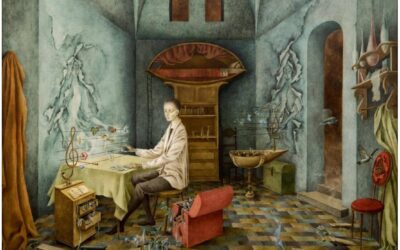

Lionel Corbett and the Religious Function of the Psyche

Lionel Corbett’s perspective on the religious function of the psyche is grounded in the idea that the experience of the sacred or the numinous is a fundamental aspect of human psychology, one that arises from the deeper, archetypal layers of the unconscious. For Corbett, the numinous is not a separate realm of experience, but is intimately bound up with the core of the psyche itself, the transpersonal ordering center that he calls the Self.

In this view, the Self is not merely a psychological construct or a product of individual experience, but is a transcendent, organizing principle that seeks meaning, purpose, and wholeness. It is the source of our deepest values and aspirations, and is experienced as a sacred or divine presence that guides and directs our lives.

Religion, in Corbett’s perspective, is the way in which the ego navigates its relationship to this numinous core of the psyche. It is the framework of beliefs, practices, and rituals that allow individuals to connect with the sacred dimensions of their own being, and to find meaning and purpose in their lives.

However, for Corbett, the religious function of the psyche is not limited to any one particular set of beliefs or practices. Rather, it is a universal human capacity, one that can be expressed in a wide variety of cultural and historical contexts. Whether through traditional religious practices, nature-based spirituality, artistic creativity, or the numinous experiences of everyday life, individuals have the potential to connect with the deeper, sacred dimensions of their own psyche.

Ritual, in this context, serves as a container for the experience of the numinous, a way of creating a sacred space in which individuals can approach and honor the divine within themselves and the world around them. Through the use of symbolic actions, gestures, and invocations, ritual creates a bridge between the ego and the Self, allowing individuals to access the transformative power of the numinous and to integrate it into their daily lives.

What sets Corbett’s perspective apart from other thinkers is his grounding of the religious function of the psyche in the archetypal depths of the unconscious, and his emphasis on the numinous as a universal human capacity. While other perspectives may focus on the cultural or social dimensions of religion, Corbett sees the experience of the sacred as a fundamental aspect of human nature, one that arises from the deeper layers of the psyche and is not dependent on any particular set of beliefs or practices.

From this perspective, prehistoric spirituality would have been a direct engagement with the numinous dimensions of the psyche, an unmediated encounter with the divine that was not necessarily filtered through the lens of culture or language. These early forms of religion would have been deeply connected to the natural world and the cycles of life and death, and would have provided a way for individuals to connect with the deeper, archetypal dimensions of their own being.

For contemporary psychotherapy, Corbett’s perspective offers a powerful framework for understanding the spiritual dimensions of the human experience, and for integrating them into the practice of psychotherapy. By recognizing the ways in which the numinous arises in the lives of clients, whether through dreams, synchronicities, or other forms of spiritual experience, therapists can help individuals to connect with the deeper sources of meaning and purpose that reside within their own psyche.

This may involve the use of techniques such as active imagination, dream analysis, or contemplative practices, as well as the exploration of clients’ spiritual or religious beliefs and practices. It may also involve a willingness on the part of the therapist to engage with their own spiritual or numinous experiences, and to bring a sense of openness and reverence to the therapeutic process.

At a broader level, Corbett’s emphasis on the universality of the religious function suggests that psychotherapy itself can be understood as a form of spiritual practice, a way of facilitating the process of individuation and self-realization that is at the heart of the human journey. By creating a space in which individuals can explore the deeper dimensions of their own psyche, and connect with the numinous aspects of their own being, psychotherapy can serve as a powerful catalyst for personal and collective transformation.

Ultimately, Corbett’s perspective challenges us to recognize the centrality of the spiritual dimension in human experience, and to approach it with a sense of openness, curiosity, and reverence. By honoring the numinous aspects of the psyche, and creating spaces in which they can be explored and integrated, we can develop a more holistic and transformative approach to psychotherapy, one that recognizes the sacred depths of the human experience and seeks to facilitate the process of individuation and self-realization.

Anthony Stevens and the Archetypal Roots of Religious Experience

Anthony Stevens‘ perspective on the evolutionary origins of religious experience is grounded in the idea that humans have an innate predisposition towards spirituality, one that is rooted in the deep evolutionary history of our species. Drawing on the work of Carl Jung and other scholars of comparative religion, Stevens argues that the capacity for numinous experience is a fundamental aspect of human nature, one that has been shaped by the same evolutionary forces that have given rise to other universal human traits and behaviors.

For Stevens, the archetypes that Jung described are not merely symbolic or metaphorical constructs, but are biologically-based patterns of perception and behavior that have evolved over millions of years to promote survival and reproduction. Just as other animals have innate tendencies towards mating, territoriality, and social bonding, humans have evolved a “religious instinct” or predisposition to experience the numinous, to seek meaning and purpose, and to form deep emotional bonds with caregivers, kin, and social groups.

In this view, the experience of the sacred is not a separate realm of human experience, but is intimately bound up with the innate, archetypal structures of the psyche. Whether through the experience of awe and wonder in the face of nature’s beauty and power, the sense of deep connection and belonging that arises in the context of social bonding and communal ritual, or the transformative experiences of self-transcendence and unity that characterize mystical states, the capacity for numinous experience is a fundamental aspect of what it means to be human.

The purpose of religious belief and practice, in this context, is to provide a framework for the expression and cultivation of these innate spiritual capacities. Through the use of ritual, symbolism, and other forms of cultural expression, religious traditions create a shared language and set of practices that allow individuals to connect with the deeper, archetypal dimensions of their own psyche, and to find meaning and purpose in their lives.

However, for Stevens, the specific forms that religious belief and practice take are less important than the underlying archetypal structures that give rise to them. While the beliefs and practices of different cultures and traditions may vary widely, the capacity for numinous experience itself is a universal human trait, one that is grounded in the deep evolutionary history of our species.

What sets Stevens’ perspective apart from other thinkers is his emphasis on the biological and evolutionary roots of religious experience, and his integration of these insights with the archetypal psychology of Jung. By grounding spirituality in the concrete realities of human evolution and biology, Stevens provides a powerful framework for understanding the deep, instinctual roots of religious behavior, and for exploring the ways in which these capacities can be cultivated and expressed in a variety of cultural and historical contexts.

From this perspective, prehistoric spirituality would have been a direct expression of these innate, archetypal capacities, a way of connecting with the deeper dimensions of the psyche and finding meaning and purpose in the face of the challenges and uncertainties of early human life. These early forms of religion would have been deeply connected to the natural world and the cycles of life and death, and would have provided a way for individuals and communities to bond together and create shared systems of meaning and value.

For contemporary psychotherapy, Stevens’ perspective offers a powerful framework for understanding the spiritual dimensions of human experience, and for integrating them into the practice of psychotherapy. By recognizing the ways in which spiritual capacities and experiences are rooted in the deep, evolutionary history of our species, therapists can help individuals to connect with the archetypal dimensions of their own psyche, and to find meaning and purpose in their lives.

This may involve the use of techniques such as dreamwork, active imagination, or ritual, as well as the exploration of clients’ spiritual or religious beliefs and practices. It may also involve a willingness on the part of the therapist to engage with their own archetypal experiences and capacities, and to bring a sense of openness and curiosity to the spiritual dimensions of the therapeutic process.

At a broader level, Stevens’ emphasis on the universality of spiritual capacities suggests that psychotherapy itself can be understood as a way of facilitating the process of individuation and self-realization that is at the heart of the human journey. By creating a space in which individuals can explore the deeper dimensions of their own psyche, and connect with the numinous aspects of their own being, psychotherapy can serve as a powerful catalyst for personal and collective transformation.

Ultimately, Stevens’ perspective challenges us to recognize the centrality of spirituality in human experience, and to approach it with a sense of openness, curiosity, and respect for its deep evolutionary roots. By honoring the archetypal dimensions of the psyche, and creating spaces in which they can be explored and integrated, we can develop a more holistic and transformative approach to psychotherapy, one that recognizes the sacred depths of the human experience and seeks to facilitate the process of individuation and self-realization.

David Abram and the Ecology of Wonder

David Abram’s perspective on the nature of the sacred and the role of the senses in human spirituality is grounded in the idea that the experience of the numinous is not a separate realm of human experience, but is intimately bound up with our embodied, sensorial engagement with the living world around us. For Abram, the sacred is not a transcendent or otherworldly reality, but is immanent within the sensuous, animate Earth itself, and is directly apprehended through our bodily participation in the world.

In this view, the experience of wonder and enchantment that arises in the face of nature’s beauty and mystery is not a mere subjective projection or cultural construct, but is a direct, immediate encounter with the sentience and agency of the more-than-human world. The wind, the trees, the mountains, and the rivers are not merely inert matter or resources for human use, but are living, communicative presences that speak to us in the language of sensory experience.

For Abram, this animistic way of perceiving the world is not a primitive or irrational mode of consciousness, but is a sophisticated and nuanced attunement to the subtle signs and gestures of the living Earth. By learning to listen to the voices of the wind, the trees, and the animals, we can begin to access a deeper wisdom and intelligence that is inherent in the natural world itself, and to recognize our own participation in the larger community of life.

The purpose of spiritual practice, in this context, is to cultivate and deepen our sensorial engagement with the living world, and to re-awaken our capacity for wonder and enchantment in the face of nature’s mystery and beauty. Through practices such as mindfulness, contemplation, and nature-based ritual, we can learn to attune ourselves to the subtle rhythms and energies of the Earth, and to recognize our own intimate connection to the larger web of life.

However, for Abram, this ecological and animistic perspective is not simply a matter of individual spiritual growth or personal fulfillment, but is a crucial task for the survival and flourishing of the entire planet. In a world that is increasingly dominated by a mechanistic and disenchanted worldview, the recovery of our capacity for wonder and enchantment is essential for the healing of the Earth and the renewal of our relationship with the living world.

What sets Abram’s perspective apart from other thinkers is his emphasis on the primacy of sensory experience in human spirituality, and his grounding of the sacred in the embodied, ecological reality of the living Earth. While other perspectives may focus on the cognitive or intellectual dimensions of religious belief and practice, Abram sees the experience of the numinous as a fundamentally bodily and sensorial phenomenon, one that arises from our direct, felt participation in the world around us.

From this perspective, prehistoric spirituality would have been a deeply sensorial and place-based phenomenon, rooted in the direct, embodied encounter with the living Earth and its many voices and presences. These early forms of religion would have been characterized by a deep attunement to the natural world, and by a sense of kinship and reciprocity with the other-than-human beings that share our planet.

For contemporary psychotherapy, Abram’s perspective offers a powerful framework for understanding the ecological and embodied dimensions of human experience, and for integrating them into the practice of psychotherapy. By recognizing the ways in which our mental and emotional well-being is intimately connected to the health and vitality of the living world around us, therapists can help individuals to develop a more holistic and integrated sense of self and world.

This may involve the use of techniques such as eco-therapy, wilderness therapy, or nature-based ritual, as well as the cultivation of sensory awareness and embodied mindfulness practices that help individuals to attune themselves to the subtle rhythms and energies of the Earth. It may also involve a willingness on the part of the therapist to engage with their own sensorial and ecological experiences, and to bring a sense of wonder and reverence to the therapeutic process.

At a broader level, Abram’s emphasis on the primacy of sensory experience and the animistic dimensions of human consciousness suggests that psychotherapy itself can be understood as a way of facilitating the process of re-enchantment and reconnection with the living world. By creating a space in which individuals can explore the ecological and embodied dimensions of their own experience, and connect with the numinous aspects of the natural world, psychotherapy can serve as a powerful catalyst for personal and collective transformation.

Ultimately, Abram’s perspective challenges us to recognize the sacredness of the sensuous Earth, and to approach the natural world with a sense of wonder, reverence, and care. By cultivating our capacity for sensory awareness and embodied participation in the world around us, we can begin to heal the deep wounds of disconnection and alienation that characterize the modern

Michael Meade and the Mythic Imagination

Michael Meade’s perspective on the role of myth and the mythic imagination in human experience is rooted in the idea that myths are not merely ancient stories or cultural artifacts, but are living, dynamic expressions of the deepest truths of the human psyche. For Meade, myths are the “big dreams” of the collective unconscious, the archetypal narratives that give shape and meaning to our individual and collective experiences.

In this view, the figures and themes of myth are not simply literary devices or historical curiosities, but are powerful, numinous presences that speak directly to the deepest layers of the psyche. The gods and goddesses, heroes and tricksters of the world’s mythologies are the personified aspects of the self, the archetypal energies that animate our inner world and guide us on the journey of individuation and self-realization.

The sacred, in Meade’s perspective, is not a separate realm of experience, but is intimately bound up with the mythic imagination itself. It is through our engagement with the living symbols and narratives of myth that we are able to access the numinous dimensions of our own psyche, and to connect with the deeper sources of meaning and purpose that guide our lives.

The purpose of ritual, in this context, is to create a container for the exploration and enactment of mythic themes and narratives, to provide a sacred space in which individuals can engage with the archetypal dimensions of their own psyche and connect with the larger stories and patterns that shape their lives.

Through the use of storytelling, poetry, music, and other forms of symbolic expression, ritual allows individuals to enter into the imaginal realm of myth and to experience the transformative power of the archetypal energies that reside there.

For Meade, the self is not a fixed or static entity, but is a dynamic, unfolding process that is shaped by the individual’s engagement with the mythic dimensions of their own psyche. The task of individuation, the lifelong process of becoming one’s fullest and most authentic self, is intimately bound up with the exploration and integration of the archetypal themes and patterns that emerge in the course of one’s life journey.

What sets Meade’s perspective apart from other thinkers is his emphasis on the transformative power of the mythic imagination, and his focus on the role of myth and ritual in facilitating the process of individuation and self-realization. While other perspectives may emphasize the social or cognitive dimensions of religious experience, Meade sees myth as a fundamental aspect of the human psyche, one that is essential for the development of a deep and authentic sense of self.

From this perspective, prehistoric myths and rituals would have served as “cultural therapies,” providing individuals and communities with a shared framework of meaning and purpose, and facilitating the process of personal and collective transformation. These early forms of religion would have been deeply connected to the natural world and the cycles of life and death, and would have provided a way for individuals to connect with the archetypal dimensions of their own psyche and to find their place within the larger web of life.

For contemporary psychotherapy, Meade’s perspective offers a powerful framework for understanding the transformative potential of myth and the mythic imagination. By recognizing the ways in which our individual struggles and challenges are connected to larger archetypal patterns and themes, therapists can help clients to find meaning and purpose in their own life journeys, and to connect with the deeper sources of wisdom and resilience that reside within their own psyche.

This may involve working with dreams, stories, and other forms of symbolic expression, as well as exploring the mythic and archetypal dimensions of the client’s own life narrative. It may also involve the use of ritual and ceremonial practices, such as the creation of personal altars or the enactment of symbolic journeys, as a way of facilitating the process of transformation and healing.

At a broader level, Meade’s emphasis on the transformative power of myth suggests that psychotherapy itself can be understood as a form of modern-day mythology, a way of helping individuals to navigate the challenges and mysteries of the human experience and to find their own unique path towards wholeness and self-realization.

By becoming “mythically literate,” therapists can develop a deeper understanding of the archetypal patterns and themes that shape the human psyche, and can use this knowledge to guide their clients through the labyrinthine journey of self-discovery and transformation.

This approach to psychotherapy requires a willingness on the part of the therapist to engage with the mythic dimensions of their own psyche, and to bring a sense of imagination, creativity, and symbolic thinking to the therapeutic process. It also requires a deep respect for the power of story and the transformative potential of the mythic imagination, and a recognition of the ways in which our individual stories are woven into the larger tapestry of human experience.

Ultimately, Meade’s perspective challenges us to recognize the vital importance of myth and the mythic imagination in human life, and to approach the task of psychotherapy with a sense of wonder, curiosity, and reverence for the deep mysteries of the psyche. By honoring the mythic dimensions of our own experience, and by creating spaces in which these dimensions can be explored and integrated, we can begin to tap into the transformative power of the mythic imagination, and to find our own unique path towards wholeness, meaning, and purpose in life.

The Path to a Better Psychotherapy

The insights and perspectives of these thinkers offer a rich and multifaceted framework for understanding the origins and functions of prehistoric religion, the enduring significance of pagan spirituality, and the implications of these traditions for the practice of psychotherapy and the cultivation of psychological well-being in the contemporary world.

By drawing upon the insights of neuroscience, evolutionary psychology, anthropology, philosophy, and ecology, these thinkers provide a compelling case for the centrality of spirituality and the experience of the sacred in human life, and for the need to re-integrate these dimensions into our understanding of the self and the world.

Moreover, by exploring the ways in which religious beliefs and practices are shaped by the complex interplay of biological, cultural, and environmental factors, these thinkers challenge the notion of religion as a purely individual or subjective phenomenon, and suggest that spirituality is a fundamental aspect of human nature that is rooted in our evolutionary history and our embodied engagement with the living world.

For the practice of psychotherapy, these insights offer a powerful framework for re-imagining the therapeutic process as a sacred and transformative encounter, one that honors the numinous dimensions of human experience and that seeks to facilitate a deeper connection to the self, the community, and the larger web of life.

By drawing upon the wisdom and practices of ancient traditions, such as shamanism, ritual, and nature-based spirituality, therapists can help individuals to access the healing and transformative power of the psyche, and to develop a more holistic and integrated sense of self and world. At the same time, by recognizing the ways in which personal growth and healing are intimately connected to the health and vitality of the larger ecosystem, therapists can contribute to the project of cultural and ecological transformation, and help to create a more sustainable and life-affirming world.

Ultimately, the integration of these perspectives into the field of psychology offers a pathway toward a more soulful and transformative approach to healing and growth, one that honors the sacred depths of the psyche and the interconnectedness of all life. By embracing the wisdom of the ancestors and the insights of contemporary science, we can begin to create a new vision of mental health and well-being that is grounded in the timeless truths of the human spirit and the living Earth.

In this vision, the self is not a isolated, autonomous entity, but is a dynamic, relational process that emerges from the complex interplay of biology, culture, and environment. The psyche is not a blank slate or a mechanical system, but is a living, creative force that is imbued with archetypal patterns and numinous energies. And the sacred is not a separate realm of existence, but is the very ground of being, the mysterious and awe-inspiring presence that animates all things.

By re-integrating these dimensions into our understanding of the self and the world, we can begin to heal the fragmentation and alienation that characterize so much of modern life, and to cultivate a deeper sense of meaning, purpose, and belonging. We can learn to listen to the voices of the ancestors and the land, to honor the cycles and seasons of the Earth, and to celebrate the beauty and mystery of existence.

And in doing so, we can begin to create a world that is more just, compassionate, and sustainable, a world that honors the dignity and worth of all beings, and that recognizes the intrinsic value and sacredness of life itself. This is the great work of our time, the challenge and the opportunity that lies before us, and it is a work that requires the participation and contribution of us all.

May we have the courage, the wisdom, and the love to embrace this work, and to create a future that is worthy of the dreams and aspirations of all those who have come before us, and all those who will come after. May we remember that we are not alone in this journey, but are part of a vast and ancient community of life, a community that includes the ancestors, the spirits, the land, and all the beings with whom we share this precious planet. And may we walk forward together, in beauty, in wonder, and in peace.

As we continue to explore the implications of these thinkers’ ideas for the field of psychology and the practice of psychotherapy, it becomes clear that their insights offer a radical challenge to the dominant paradigms of mental health and well-being in the modern world.

For too long, psychology has been dominated by a reductionistic and mechanistic view of the self, one that sees the mind as a kind of computer and the brain as a kind of machine. This view has led to a narrow focus on symptoms and pathology, and a neglect of the deeper dimensions of human experience, such as meaning, purpose, and spirituality.

In this view, the goal of psychotherapy is not simply to alleviate symptoms or to promote adaptation to social norms, but to facilitate a deeper encounter with the numinous dimensions of the psyche, and to help individuals to cultivate a sense of wholeness, authenticity, and connection to the larger community of life. This may involve the use of a wide range of practices and techniques, from depth psychology and eco-therapy to shamanic healing and ritual, that allow individuals to access the transformative power of the unconscious and the sacred.

At the same time, this view of psychotherapy requires a fundamental shift in the role of the therapist, from that of an expert or authority figure to that of a guide or facilitator who helps individuals to navigate the mysteries of the psyche and the challenges of the human condition. This shift requires a deep humility and respect for the wisdom and agency of the individual, as well as a willingness to engage with the spiritual and mythic dimensions of experience that are often neglected or pathologized in mainstream psychology.

Moreover, this view of psychotherapy requires a recognition of the ways in which personal healing and transformation are intimately connected to the larger project of cultural and ecological healing. By helping individuals to develop a deeper sense of connection to the living world and to the larger community of life, therapists can contribute to the creation of a more sustainable and life-affirming culture, one that honors the intrinsic value and sacredness of all beings.

The Path to a Better World

This is not an easy task, and it requires a willingness to challenge the dominant assumptions and values of the modern world, including the myth of progress, the cult of individualism, and the exploitation of nature. It requires a rediscovery of the ancient wisdom and practices that have sustained human communities for millennia, and a re-integration of these traditions into the contemporary context.

But it is a task that is essential for the survival and flourishing of our species and the planet as a whole. As we face the unprecedented challenges of climate change, social inequality, and the loss of biodiversity, we need a new vision of mental health and well-being that is grounded in the recognition of our deep interconnectedness with each other and with the living Earth.

The thinkers we have explored in this analysis offer a pathway toward this new vision, one that honors the sacred depths of the psyche and the living world, and that seeks to create a more just, compassionate, and sustainable future for all beings. By embracing their insights and integrating them into the practice of psychotherapy and the larger project of cultural transformation, we can begin to heal the wounds of the past and to create a world that is more in alignment with the deepest truths of the human spirit and the living Earth.

Bibliography:

Abram, D. (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Pantheon Books.

Abram, D. (2010). Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books.

Barrett, L. (2011). Beyond the Brain: How Body and Environment Shape Animal and Human Minds. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Corbett, L. (1996). The Religious Function of the Psyche. London: Routledge.

Corbett, L. (2007). Psyche and the Sacred: Spirituality Beyond Religion. New Orleans, LA: Spring Journal Books.

Eliade, M. (1957). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Freud, S. (1927). The Future of an Illusion. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Freud, S. (1930). Civilization and Its Discontents. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. New York: Harper & Row.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and His Symbols. New York: Doubleday.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Meade, M. (1993). Men and the Water of Life: Initiation and the Tempering of Men. New York: HarperCollins.

Meade, M. (2010). Fate and Destiny: The Two Agreements of the Soul. Seattle, WA: Greenfire Press.

Otto, R. (1923). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schore, A. N. (1994). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: The Neurobiology of Emotional Development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Schore, A. N. (2003). Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stevens, A. (1982). Archetypes: A Natural History of the Self. New York: Quill.

Stevens, A. (1993). The Two Million-Year-Old Self. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Turner, V. (1967). The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. O. (1992). The Diversity of Life. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Further Reading: Abram, D. (2011). Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Vintage Books.

Aizenstat, S. (1995). Dream Tending. New Orleans, LA: Spring Journal, Inc.

Bache, C. M. (2000). Dark Night, Early Dawn: Steps to a Deep Ecology of Mind. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Berry, T. (1988). The Dream of the Earth. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Berry, T. (1999). The Great Work: Our Way into the Future. New York: Bell Tower.

Brody, H. (1981). Maps and Dreams. New York: Pantheon Books.

Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York: Pantheon Books.

Chalquist, C. (2007). Terrapsychology: Reengaging the Soul of Place. New Orleans, LA: Spring Journal Books.

Davis, W. (2009). The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World. Toronto: House of Anansi Press.

Deloria, V. (1973). God is Red. New York: Grosset & Dunlap.

Devereux, P. (2000). The Sacred Place: The Ancient Origins of Holy and Mystical Sites. London: Cassell & Co.

Durkheim, E. (1915). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Eliade, M. (1958). Patterns in Comparative Religion. New York: Sheed & Ward.

Eliade, M. (1969). The Quest: History and Meaning in Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Frazer, J. G. (1922). The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. New York: Macmillan.

Grof, S. (1988). The Adventure of Self-Discovery. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Halifax, J. (1979). Shamanic Voices: A Survey of Visionary Narratives. New York: E. P. Dutton.

Harner, M. (1980). The Way of the Shaman. New York: Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1983). Healing Fiction. Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Press.

Hillman, J. (1996). The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. New York: Random House.

Ingerman, S. (1991). Soul Retrieval: Mending the Fragmented Self. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco.

Jung, C. G. (1933). Modern Man in Search of a Soul. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Pantheon Books.

Keen, S. (1983). The Passionate Life: Stages of Loving. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

Kellert, S. R., & Wilson, E. O. (Eds.). (1993). The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Laszlo, E. (1972). Introduction to Systems Philosophy: Toward a New Paradigm of Contemporary Thought. New York: Harper & Row.

Leopold, A. (1949). A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There. New York: Oxford University Press.

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Metzner, R. (1999). Green Psychology: Transforming Our Relationship to the Earth. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the Soul: A Guide for Cultivating Depth and Sacredness in Everyday Life. New York: HarperCollins.

Narby, J. (1998). The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam.

Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Plotkin, B. (2003). Soulcraft: Crossing into the Mysteries of Nature and Psyche. Novato, CA: New World Library.

Plotkin, B. (2008). Nature and the Human Soul: Cultivating Wholeness and Community in a Fragmented World. Novato, CA: New World Library.

Roszak, T. (1992). The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Roszak, T., Gomes, M. E., & Kanner, A. D. (Eds.). (1995). Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Sabini, M. (Ed.). (2002). The Earth Has a Soul: C.G. Jung on Nature, Technology & Modern Life. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Seed, J., Macy, J., Fleming, P., & Naess, A. (1988). Thinking Like a Mountain: Towards a Council of All Beings. Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers.

Shepard, P. (1982). Nature and Madness. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Snyder, G. (1990). The Practice of the Wild. San Francisco, CA: North Point Press.

Spretnak, C. (1991). States of Grace: The Recovery of Meaning in the Postmodern Age. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco.

Tarnas, R. (1991). The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas that Have Shaped Our World View. New York: Harmony Books.

Tarnas, R. (2006). Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. New York: Viking.

Tedlock, B. (2005). The Woman in the Shaman’s Body: Reclaiming the Feminine in Religion and Medicine. New York: Bantam Books.

Teilhard de Chardin, P. (1959). The Phenomenon of Man. New York: Harper & Row.

Underhill, E. (1911). Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness. New York: E. P. Dutton.

Watkins, M. (1986). Invisible Guests: The Development of Imaginal Dialogues. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

Watts, A. (1966). The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are. New York: Pantheon Books.

Wilber, K. (1995). Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (1996). A Brief History of Everything. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wordsworth, W., & Coleridge, S. T. (1798). Lyrical Ballads. London: J. & A. Arch.

Further Reading List:

Abram, D. (2011). Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York: Vintage Books.

- An exploration of the interconnectedness of all life and the importance of rekindling our sensorial engagement with the natural world.

Aizenstat, S. (2009). Dream Tending: Awakening to the Healing Power of Dreams. New Orleans, LA: Spring Journal Books.

- A guide to working with dreams as a source of insight, healing, and transformation.

Bache, C. M. (2000). Dark Night, Early Dawn: Steps to a Deep Ecology of Mind. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- An examination of the transformative potential of non-ordinary states of consciousness and their implications for our understanding of the mind-body relationship and the nature of reality.

Barks, C. (2010). Rumi: Soul Fury: Rumi and Shams Tabriz on Friendship. New York: HarperOne.

- A collection of poems and teachings from the 13th-century Sufi mystic Rumi, exploring themes of love, spiritual awakening, and the nature of the self.

Berman, M. (1981). The Reenchantment of the World. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- A critique of the disenchanted worldview of modern science and a call for a renewed sense of wonder and mystery in our relationship to the cosmos.

Bernstein, J. S. (2005). Living in the Borderland: The Evolution of Consciousness and the Challenge of Healing Trauma. New York: Routledge.

- An exploration of the relationship between trauma, dissociation, and the evolution of human consciousness, drawing on insights from depth psychology, neuroscience, and indigenous wisdom traditions.

Bordo, S. (1987). The Flight to Objectivity: Essays on Cartesianism and Culture. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- A feminist critique of the Cartesian dualism between mind and body and its implications for our understanding of knowledge, subjectivity, and culture.

Brach, T. (2003). Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life with the Heart of a Buddha. New York: Bantam.

- A guide to cultivating self-compassion, mindfulness, and emotional healing, drawing on insights from Buddhist psychology and Western psychotherapy.

Buber, M. (1958). I and Thou. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- A philosophical and spiritual exploration of the nature of relationship and the distinction between the “I-It” and “I-Thou” modes of being.

Campbell, J. (1988). The Power of Myth. New York: Doubleday.

- A series of interviews with the renowned mythologist Joseph Campbell, exploring the role of myth and ritual in human culture and the search for meaning and purpose in life.

Capra, F. (1975). The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels Between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism. Berkeley, CA: Shambhala.

- An examination of the similarities between the worldviews of modern physics and Eastern spiritual traditions, such as Taoism and Buddhism.

Chödrön, P. (2001). The Places That Scare You: A Guide to Fearlessness in Difficult Times. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

- A guide to cultivating courage, compassion, and resilience in the face of life’s challenges, drawing on insights from Buddhist teachings and practices.

Corbin, H. (1969). Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- An exploration of the visionary and imaginal dimensions of Islamic mysticism, focusing on the work of the 12th-century Sufi philosopher Ibn ‘Arabi.

Damasio, A. (2000). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace.

- A neuroscientific investigation of the role of emotion and bodily sensation in the emergence of consciousness and the sense of self.

Davidson, R. J., & Begley, S. (2012). The Emotional Life of Your Brain: How Its Unique Patterns Affect the Way You Think, Feel, and Live–and How You Can Change Them. New York: Hudson Street Press.

- An exploration of the neuroscience of emotion and its implications for mental health, well-being, and personal transformation.

Davis, W. (2009). The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World. Toronto: House of Anansi Press.

- An anthropological exploration of the diversity of human cultures and the importance of preserving indigenous knowledge and ways of being in the face of globalization and environmental destruction.

Deloria, V. (1994). God is Red: A Native View of Religion. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

- A critique of Western religion and a defense of Native American spirituality, arguing for the importance of a land-based, community-centered approach to the sacred.

Devall, B., & Sessions, G. (1985). Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered. Salt Lake City, UT: Peregrine Smith Books.

- A seminal text in the deep ecology movement, advocating for a shift in human consciousness and values toward a more ecocentric and sustainable way of being in the world.

Foster, S., & Little, M. (1989). The Book of the Vision Quest: Personal Transformation in the Wilderness. New York: Prentice Hall Press.

- A guide to the practice of vision questing and wilderness rites of passage as a means of personal growth, self-discovery, and spiritual awakening.

Gendlin, E. T. (1982). Focusing. New York: Bantam Books.

- A guide to the practice of focusing, a somatic approach to psychological healing and self-awareness that emphasizes the wisdom of the body and the felt sense of experience.

Gimbutas, M. (1989). The Language of the Goddess. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

- An exploration of the prehistoric origins of goddess worship and the symbolic language of ancient European cultures, based on archaeological evidence and mythological analysis.

Goodman, F. D. (1990). Where the Spirits Ride the Wind: Trance Journeys and Other Ecstatic Experiences. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- An anthropological study of the cross-cultural phenomenon of trance and ecstatic experience, drawing on fieldwork with shamanic cultures around the world.

Glendinning, C. (1994). My Name is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

- A critique of the addictive and destructive patterns of Western culture and a call for a more authentic, embodied, and Earth-honoring way of life.

Griffin, S. (1995). The Eros of Everyday Life: Essays on Ecology, Gender and Society. New York: Doubleday.

- A collection of essays exploring the intersections of ecology, feminism, and spirituality, and the importance of reconnecting with the erotic dimensions of life.

Halifax, J. (1991). The Fruitful Darkness: Reconnecting with the Body of the Earth. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco.

- An exploration of the transformative power of darkness, both literal and metaphorical, and its role in spiritual growth, creativity, and ecological awareness.

Harner, M. (1990). The Way of the Shaman. New York: HarperOne.

- A classic introduction to shamanic practices and worldviews, based on the author’s fieldwork with indigenous cultures in the Americas.

Hillman, J. (1997). The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. New York: Warner Books.

- An exploration of the idea of the “acorn theory” of human development, which holds that each person has a unique calling or destiny that is encoded in their soul from birth.

Hogan, L. (1995). Dwellings: A Spiritual History of the Living World. New York: W.W. Norton.

- A poetic and lyrical exploration of the spiritual dimensions of the natural world, drawing on Native American traditions and personal experiences of the land.

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

- A collection of essays exploring the intersection of indigenous knowledge, plant ecology, and the search for a more sustainable and reciprocal relationship with the Earth.

Laszlo, E. (2004). Science and the Akashic Field: An Integral Theory of Everything. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions.

- An exploration of the idea of the “Akashic field,” a unified field of cosmic memory and intelligence that underlies the fabric of reality.

Macy, J. (1991). World as Lover, World as Self. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press.

- A collection of essays and practices exploring the Buddhist concept of “dependent co-arising” and its implications for ecological activism and personal transformation.

Metzner, R. (1999). Green Psychology: Transforming Our Relationship to the Earth. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

- An examination of the psychological and spiritual dimensions of the ecological crisis, and a call for a new “green psychology” that reconnects humans with the living Earth.

Mindell, A. (2002). The Dreambody in Relationships. Portland, OR: Lao Tse Press.

- An exploration of the ways in which our unconscious “dreambodies” shape our relationships and interactions with others, and how to work with these energies for personal and interpersonal healing.

Plotkin, B. (2003). Soulcraft: Crossing into the Mysteries of Nature and Psyche. Novato, CA: New World Library.

- A guide to the practice of “soulcraft,” a nature-based approach to psychological and spiritual growth that draws on wilderness rites of passage, depth psychology, and ecopsychology.

Roszak, T. (2001). The Voice of the Earth: An Exploration of Ecopsychology. Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes Press.

- A seminal text in the field of ecopsychology, exploring the psychological dimensions of the ecological crisis and the need for a new “ecological ego” that recognizes the interdependence of self and planet.

Sams, J., & Carson, D. (1994). Medicine Cards: The Discovery of Power Through the Ways of Animals. Santa Fe, NM: Bear & Company.

- A guide to working with animal archetypes and totems as a means of personal growth and spiritual insight, based on Native American traditions.

Shepard, P. (1998). Coming Home to the Pleistocene. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- An exploration of the evolutionary origins of human culture and the ways in which modern society has become disconnected from the rhythms and patterns of the natural world.

Smith, H. (1991). The World’s Religions: Our Great Wisdom Traditions. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco.

- A classic comparative study of the world’s major religious traditions, exploring their core teachings, practices, and historical development.

Swimme, B., & Berry, T. (1994). The Universe Story: From the Primordial Flaring Forth to the Ecozoic Era–A Celebration of the Unfolding of the Cosmos. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco.

- A cosmological and evolutionary account of the history of the universe, from the Big Bang to the emergence of human consciousness and the challenges of the ecological crisis.

Tarnas, R. (2006). Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. New York: Viking.

- An exploration of the correspondences between planetary cycles and the archetypal patterns of human history and psychology, based on insights from depth psychology and archetypal astrology.

Vaughan-Lee, L. (2000). Love is a Fire: The Sufi’s Mystical Journey Home. Inverness, CA: Golden Sufi Center.

- A poetic and mystical exploration of the Sufi path of love and devotion, drawing on the teachings of Rumi, Ibn ‘Arabi, and other Sufi masters.

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

- An integrative framework for understanding the evolution of human consciousness and the development of the self, drawing on insights from Eastern and Western psychology, spirituality, and philosophy.AnthropologyNeolithic ArchitectureVictor TurnerLouise BarettAllan ShoreMichael MeadeLionel CorbettAnthony Stevens

0 Comments