What is BPD and what are the Millon subtypes:

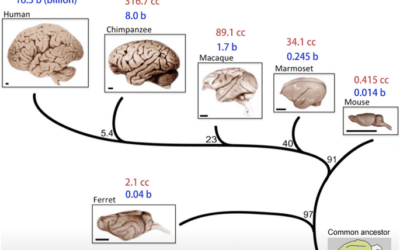

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a complex and challenging mental health condition that affects how individuals perceive themselves, relate to others, and manage their emotions. It’s characterized by a pattern of instability in self-image, interpersonal relationships, and emotions, often leading to impulsive behaviors, intense mood swings, and a deep fear of abandonment. People with BPD frequently struggle with regulating their emotions, which can lead to emotional outbursts, self-harm, and a pervasive sense of emptiness. The disorder often emerges in adolescence or early adulthood and can have profound impacts on various aspects of a person’s life, including their relationships, work, and overall well-being. It is almost always linked to complex trauma in childhood but newer research indicates it can also be caused by structural deformities in the brain.

Individuals with BPD often experience intense emotional pain, difficulty forming stable relationships, and a sense of emptiness that can be overwhelming. The unpredictable mood swings and impulsive behaviors can disrupt daily life and hinder personal and professional growth. Treatment for BPD is notoriously complex due to the multifaceted nature of the disorder. The intense emotional dysregulation and deep-seated fears of abandonment make establishing a therapeutic alliance challenging. Moreover, the fluctuating nature of BPD symptoms can complicate treatment planning, as progress may be accompanied by setbacks. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) has shown promise in treating BPD, but it requires significant commitment and effort from both patients and clinicians. The delicate balance between providing support and maintaining boundaries, coupled with the chronic nature of the disorder, makes treating BPD a demanding task for mental health professionals.

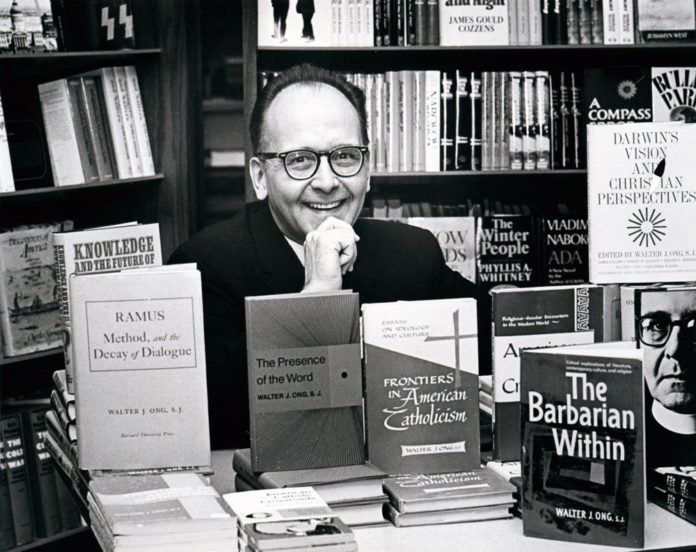

Understanding the Subtypes of Borderline Personality Disorder Proposed by Theodore Millon: A Missed Opportunity

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a complex mental health condition characterized by unstable emotions, self-image, and interpersonal relationships. Over the years, researchers and clinicians have explored various ways to categorize and understand BPD in more detail. One such attempt was made by Theodore Millon, a prominent psychologist known for his work on personality disorders. Millon proposed subtypes of BPD that aimed to provide a more nuanced understanding of the disorder. While these subtypes offered potential benefits, they were not widely adopted for various reasons. In this article, we’ll explore Millon’s proposed subtypes of BPD, their potential usefulness, the reasons for their lack of adoption, and the impact of removing Cluster B from the DSM-5.

The Subtypes of BPD Proposed by Theodore Millon

Theodore Millon suggested four subtypes of BPD that aimed to capture the diverse presentations of the disorder:

Discouraged Borderline:

This subtype is characterized by individuals who feel overwhelmed by their emotions and tend to experience intense depression and feelings of emptiness. They often struggle with self-worth and may engage in self-destructive behaviors as a way to cope. Individuals within the Discouraged Borderline subtype of BPD often grapple with overwhelming emotions, frequently experiencing deep episodes of depression and a pervasive sense of emptiness. This subtype is characterized by a profound struggle with self-worth and a tendency to internalize negative feelings. These individuals may engage in self-destructive behaviors as a means of coping with their emotional turmoil. Their interpersonal relationships can be marked by intense mood swings and a yearning for connection, while simultaneously fearing rejection and abandonment.

Impulsive Borderline:

Individuals within this subtype exhibit impulsive and unpredictable behaviors, often driven by their intense emotional experiences. They might struggle with substance abuse, engage in risky behaviors, and have difficulties with impulse control. The Impulsive Borderline subtype is characterized by impulsive and unpredictable behaviors that are driven by intense emotional experiences. Individuals in this category may have difficulties controlling their impulses, often leading to engaging in risky behaviors such as substance abuse, reckless driving, or impulsive spending. Their emotions can be quick to escalate, contributing to volatile relationships and difficulty in maintaining stability. This subtype reflects a struggle to manage the strong emotions that fuel their impulsive actions.

Petulant Borderline:

This subtype involves individuals who are irritable, impatient, and demanding. They may display frequent outbursts of anger and resentment, which can strain their interpersonal relationships. Individuals within the Petulant Borderline subtype tend to exhibit a distinctive irritability, impatience, and a pronounced sense of entitlement. Their emotional volatility is manifested through frequent and intense displays of anger and resentment. These individuals may struggle with forming and maintaining healthy relationships due to their tendency to challenge or provoke others. The petulant subtype highlights a consistent need for attention and validation, often resulting in interpersonal conflicts and emotional turmoil.

Self-Destructive Borderline:

Individuals in this subtype exhibit self-harming behaviors and may even engage in suicidal ideation or attempts. They struggle with intense self-loathing and may have a history of trauma. The Self-Destructive Borderline subtype is characterized by a particularly intense self-loathing and a history of self-harming behaviors. Individuals in this category often struggle with suicidal ideation or even engage in suicide attempts. Their emotional pain is turned inward, resulting in behaviors that harm themselves physically or emotionally. This subtype underscores the profound internal struggle these individuals face, often stemming from past trauma or difficult life experiences.

Potential Usefulness of the Subtypes

I always found the Millon’s subtypes helpful for conceptualizing the “flavor” of the emotions and avoidance patterns under different types of BPD. Patient’s seemed to like them to as the BPD diagnosis can be monolithic and the subtypes make the diagnosis more personal and easier to conceptualize and change. Millon’s proposed subtypes could have provided clinicians with a more personalized and tailored approach to diagnosing and treating BPD with better evidence based techniques being indicated for different subtypes of the disorder. . By recognizing distinct patterns within the disorder, mental health professionals might have been better equipped to provide targeted interventions, which could lead to improved outcomes for individuals struggling with BPD. Additionally, these subtypes could have contributed to a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving BPD, potentially aiding in the development of more effective treatment strategies.

Reasons for Lack of Adoption

Despite the potential benefits, Millon’s subtypes of BPD were not widely adopted within the clinical and research communities. One reason for this lack of adoption could be the complexity and subjectivity involved in classifying individuals into specific subtypes. BPD itself already presents a wide range of symptoms that can overlap and change over time, making it challenging to fit individuals neatly into predefined categories.

Moreover, the diagnostic criteria for BPD have evolved over time, and the field has shifted towards a dimensional approach that focuses on the severity of specific traits rather than rigid subtyping. This shift reflects a growing understanding that personality disorders exist on a spectrum and that individuals may exhibit varying combinations of traits.

Cluster B Removal from DSM-5 and DSM-5 TR: Impact and Downsides

In the context of personality disorders, Cluster B refers to a group that includes BPD, along with Antisocial Personality Disorder, Narcissistic Personality Disorder, and Histrionic Personality Disorder. I always found this cluster system helpful because it group disorders often caused by emotional neglect and abuse as the cause that were handled with different coping styles. These disorders often cooccur in families so the cluster system helped patients understand the similar pain that the family members were all reacting too even though their behavior was different.

The DSM-5, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, removed the concept of clusters for personality disorders. This change aimed to reflect the heterogeneous nature of these disorders and move towards a more trait-based diagnostic system. This reflects the move towards the fixation on symptoms and not their causes. As a social worker I find this approach counter intuitive because it removes the environment from the diagnostic system even more than before. While the removal of Cluster B was intended to increase accuracy and flexibility in diagnosing personality disorders, it also has downsides. related to one another, which could aid clinicians in forming a comprehensive treatment approach. Without the clustering system, clinicians might find it more challenging to identify overarching patterns and associations between different personality disorders.

Theodore Millon’s proposal of subtypes for BPD showcased an attempt to refine our understanding of this complex disorder. While the subtypes had potential benefits, the evolving nature of diagnostic approaches and the emphasis on trait-based assessment contributed to their lack of adoption. The removal of Cluster B from the DSM-5 reflects a broader shift in how personality disorders are conceptualized, though it also presents challenges in recognizing patterns among related disorders. Removing the Millon borderline subtypes and the cluster system further distances the conceptualization of BPD diagnosis from the trauma that causes it. This makes it harder for providers to identify and treat trauma and its unique expression in BPD clinically.

Bibliography:

Millon, T., & Davis, R. D. (1996). Disorders of personality: DSM-IV and beyond. John Wiley & Sons.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

References:

Gunderson, J. G. (2009). Borderline personality disorder: A clinical guide. American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (2010). Mentalization-based treatment for borderline personality disorder. World Psychiatry, 9(1), 11-15.

Kraus, G., & Reynolds, D. J. (2001). The “A-B-C’s” of the cluster B’s: Identifying, understanding, and treating cluster B personality disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(3), 345-373.

Arntz, A., & van Genderen, H. (2009). Schema therapy for borderline personality disorder. John Wiley & Sons.

Leichsenring, F., Leibing, E., Kruse, J., New, A. S., & Leweke, F. (2011). Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet, 377(9759), 74-84.

Further Reading:

Zanarini, M. C. (Ed.). (2008). Borderline personality disorder. CRC Press.

Kernberg, O. F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. Jason Aronson.

Fonagy, P., & Bateman, A. (2006). Progress in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(1), 1-3.

Choi-Kain, L. W., & Gunderson, J. G. (2019). Borderline personality disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(8), 757-766.

Lana, F., & Fernández-San Martín, M. I. (2013). To what extent are specific psychotherapies for borderline personality disorders efficacious? A systematic review of published randomised controlled trials. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 41(4), 242-252.

Oldham, J. M. (2006). Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(1), 20-26.

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. Guilford Press.

Influential Psychologists

0 Comments