Who was Milton Erikson?

Early Life and Education

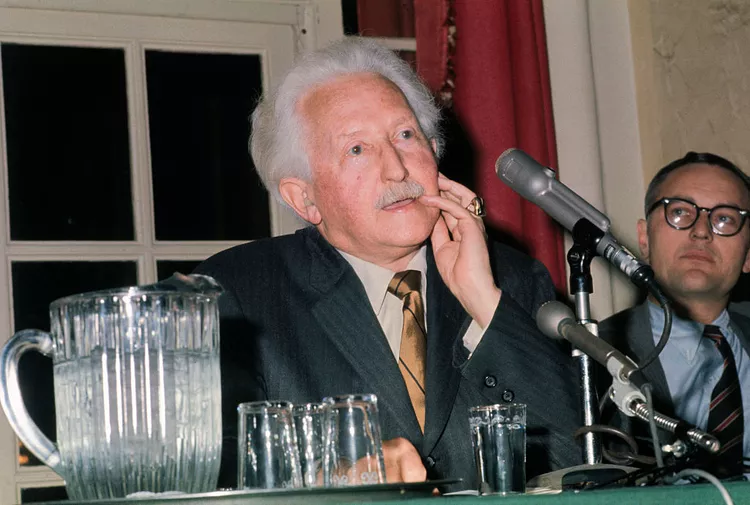

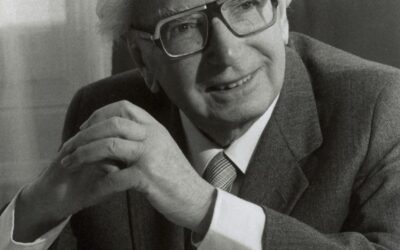

Erik Erikson was born on June 15, 1902, in Frankfurt, Germany to Karla Abrahamsen, a young Jewish woman. The identity of Erikson’s biological father was unknown, as Karla had become pregnant before her marriage. When Erikson was three, his mother married Dr. Theodor Homburger, a Jewish pediatrician, who raised Erikson as his own son. The family kept the circumstances of Erikson’s birth a secret, which contributed to Erikson’s later interest in identity development.

Erikson often felt like an outsider in his early life, being teased for looking Nordic while attending a Jewish school and later for being Jewish at his grammar school. These experiences of not quite fitting in shaped Erikson’s questions about identity formation.

After high school, Erikson wandered through Europe as an artist, pursuing his interest in identity through painting and sketching. This period of exploring different roles would later inform Erikson’s concept of the “psychosocial moratorium.”

Introduction to Psychoanalysis and Move to Vienna

In 1927, Erikson began teaching art at a Vienna school run by Dorothy Burlingham, a friend of Anna Freud. This led to Erikson’s introduction to psychoanalysis and the Freud family. Intrigued, Erikson trained at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute under Anna Freud, becoming a specialized child psychoanalyst. During this time, he also met Joan Serson, a Canadian dance instructor, who became his wife and lifelong collaborator.

Immigration to the United States and Work in Boston

As Nazism rose in 1933, Erikson and his wife left Vienna for the United States. They settled in Boston, where Erikson was the first child psychoanalyst. He taught at Harvard Medical School and had a clinical practice at Massachusetts General Hospital. Here, Erikson began developing his own theories beyond traditional Freudianism, emphasizing social and cultural factors in development.

The Creation of Erikson’s Psychosocial Development Theory

Erikson’s key contribution to psychology was his psychosocial theory of development. Diverging from Freud’s emphasis on psychosexual stages, Erikson proposed that development spanned the entire lifespan, shaped by social relationships and cultural influences. His theory outlined eight stages, each focused on a particular crisis or challenge:

Trust vs. Mistrust (Infancy, 0-18 months):

In this stage, infants learn whether they can trust the world around them, primarily through their caregivers. Consistent, reliable care leads to trust, while inconsistent or neglectful care can lead to mistrust.

Autonomy vs. Shame & Doubt (Toddlerhood, 18 months-3 years):

Toddlers begin to assert their independence. Supportive parents who allow safe exploration foster autonomy, while overprotective or highly critical parents may instill shame and doubt.

Initiative vs. Guilt (Preschool, 3-5 years):

Children start to initiate activities and assert themselves more. Encouragement supports initiative, while excessive criticism can lead to guilt.

Industry vs. Inferiority (Early School Age, 5-12 years):

Children develop a sense of competence through learning new skills. Success breeds industry, while failure or negative comparisons can lead to feelings of inferiority.

Identity vs. Role Confusion (Adolescence, 12-18 years):

Teens explore their identity and roles in society. Successfully navigating this stage leads to a strong sense of self, while difficulty can result in role confusion.

Intimacy vs. Isolation (Early Adulthood, 18-40 years):

Young adults focus on forming intimate relationships. Success leads to strong relationships, while failure can result in feelings of isolation.

Generativity vs. Stagnation (Middle Adulthood, 40-65 years):

Adults strive to create or nurture things that will outlast them, often through parenting or career. Success leads to feelings of usefulness and accomplishment, while failure can result in stagnation.

Ego Integrity vs. Despair (Late Adulthood, 65+ years):

Older adults reflect on their lives. Those who feel proud of their accomplishments achieve ego integrity, while those who have regrets may experience despair.

Developmental Stages

Each stage builds upon the previous ones, and the way an individual resolves each crisis affects their ability to deal with future stages. It’s important to note that while Erikson presented these stages as occurring at specific age ranges, the process is fluid and can vary among individuals and cultures.

Erikson proposed that successfully resolving each stage’s crisis led to acquiring specific psychological strengths and virtues necessary for the next stage. His lifespan perspective and emphasis on psychosocial factors revolutionized developmental psychology beyond Freud’s biologically based model.

Major Concepts: Identity, Generativity, and the Life Cycle

Erikson’s work centered on several key concepts. He popularized the term “identity crisis” for the challenges of forming a stable sense of self in adolescence and early adulthood. The idea of an identity formed through exploring different roles fit the rapidly changing post-war society and resonated in popular culture.

Erikson also coined the term “generativity” to represent the midlife challenge of being productive and supporting future generations. He connected individual development to the development of society and culture through this link between generations.

Erikson’s holistic “life cycle” perspective portrayed development as a lifelong process with different tasks and opportunities at each stage. This contrasted with Freud’s focus on childhood, offering a more optimistic vision of continuing possibilities for positive change throughout life.

Research on Culture and Identity

To explore how culture shapes development, Erikson conducted field work and observational studies of Native American groups like the Yurok and Sioux in the 1930s and 1940s. He analyzed how child-rearing practices and social structures influenced children’s experiences resolving conflicts like trust, autonomy, and initiative at different developmental stages.

Erikson’s emphasis on the interaction of culture and identity helped establish the cross-cultural study of human development. He showed how development is influenced by historical context and cultural values, not just biology. Erikson’s concepts of the impact of social expectations and values on identity are now central to developmental and cultural psychology.

Contributions to Psychobiography and Psychohistory

Erikson pioneered the use of psychological theory to interpret historical figures’ lives, creating the field of psychohistory. His psychobiographical studies of Martin Luther and Mahatma Gandhi analyzed how their life histories and socio-cultural contexts shaped their identities and leadership of social movements.

By examining Luther’s identity crisis and conflicts with paternal authority in Young Man Luther (1958), Erikson explored the psychological roots of his religious transformation. Gandhi’s Truth (1969), winner of the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award, portrayed Gandhi’s commitments to nonviolence and Indian nationalism as expressions of his resolution of identity challenges. These works established psychobiography as an influential approach to understanding both individual development and social history.

Practical Applications in Therapy, Education, and Social Policy

Erikson’s work provided major insights for psychological treatment, educational practices, and social programs. His emphasis on how unresolved psychosocial crises impact later development gave therapists a framework for understanding problems in the context of the individual’s current life stage and challenges.

Erikson’s portrayal of adolescence as a time of identity exploration led educational philosophers to advocate for schools to provide opportunities for trying out different social roles, values, and career paths. His concept of the “psychosocial moratorium” supported the idea of a period of exploration before taking on full adult responsibilities.

In the 1950s-60s, Erikson consulted on White House conferences on children and youth. His reports influenced the creation of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the 1965 youth service program VISTA. His emphasis on community and generativity as social responsibility informed the Great Society programs of that era.

Critiques and Limitations of Erikson’s Theories

While profoundly influential, Erikson’s theories have drawn some criticism. Feminists observed that Erikson’s stages seeming to better fit male development, with the intimacy stage not matching women’s overlapping experiences of intimacy and identity. His model was critiqued as reflecting largely Western, middle-class values.

Some empirical researchers argued that Erikson’s theory was difficult to test rigorously. They questioned whether the crises always occurred in the same order or manifested in the same ways across all cultures. Erikson acknowledged these limitations, granting the need to expand the theory beyond his own social context.

Erikson’s Personal Journey and Later Work

Erikson’s interest in identity was interwoven with his own life experiences. The son of an unknown Danish father and raised Jewish, Erikson spent much of his life as an immigrant navigating between different cultures. He never legally changed his name, signifying his own identity explorations.

Together with his wife and collaborator Joan, Erikson increasingly focused in his later work on how people sustain identity and find meaning in old age. Joan Erikson expanded her husband’s original theory to include a ninth stage after his death, describing the challenges of dystonic vs. syntonic tendencies in the 80s and 90s.

The Erikson Legacy Institute, founded by Erikson’s family, continues to extend Erikson’s work for healthy human development and social engagement. It sponsors research, educational programs, and multimedia projects that apply Erikson’s ideas to contemporary challenges of living in an ever-more globalized and diverse world.

Erikson’s Enduring Impact on Psychology and Society

Erik Erikson’s ideas about identity, psychosocial development, and the influence of culture and history on individual growth transformed the field of psychology. His perspectives remain central to developmental, personality, and social psychology.

Terms Erikson coined like “identity crisis” and “generativity” have entered the mainstream vocabulary we use to speak about self-development and social responsibility. His emphasis on identity formation in cultural context has provided key insights for education, psychotherapy, and social policy.

As the 21st century continues to bring rapid social change and questions of individual and social identity, Erikson’s investigations of these topics remain deeply relevant. The current widespread interest in links between individual development and larger historical change underscore the ongoing significance of Erikson’s approach. Erikson’s concepts offer an important foundation for understanding the interconnections of self and society in an increasingly complex world.

Timeline of Erikson’s Life

1902: Born Erik Salomonsen in Frankfurt, Germany, to Danish mother Karla Abrahamsen.

1908: His mother marries Dr. Theodor Homburger, and Erik takes his stepfather’s surname.

1920s: Wanders through Europe as an artist, struggling to find his identity.

1927: Begins teaching art and other subjects at a school in Vienna founded by Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund Freud.

1928-1933: Trains in psychoanalysis at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute.

1930: Marries Joan Serson, a Canadian dance instructor.

1933: Moves to Denmark to escape the rise of Nazism, then emigrates to the United States.

1936: Begins teaching at Harvard Medical School and practicing child psychoanalysis.

1939: Becomes a naturalized U.S. citizen and changes his name to Erik Erikson.

1950: Publishes “Childhood and Society,” introducing his theory of psychosocial development.

1950-1960: Teaches at the University of California, Berkeley, but resigns in protest over loyalty oath requirements.

1960-1970: Returns to Harvard as a professor.

1969: Wins Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award for “Gandhi’s Truth.”

1970-1974: Continues research and writing at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford.

1987-1994: Continues writing and lecturing in his later years.

1994: Dies on May 12 in Harwich, Massachusetts, at age 91.

Bibliography

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469-480.

Berzoff, J., Flanagan, L. M., & Hertz, P. (2016). Inside out and outside in: Psychodynamic clinical theory and psychopathology in contemporary multicultural contexts. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Boeree, C. G. (2006). Erik Erikson. Personality Theories. Retrieved from http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/erikson.html

Côté, J. E., & Levine, C. G. (2002). Identity formation, agency, and culture: A social psychological synthesis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crain, W. (2015). Theories of development: Concepts and applications. New York: Routledge.

Douvan, E. (1997). Erik Erikson: Critical times, critical theory. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 28(1), 15-21.

Elkind, D. (1970). Erik Erikson’s eight ages of man. New York Times Magazine, April 5, 1970.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and Society. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1958). Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1964). Insight and Responsibility. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1969). Gandhi’s Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1975). Life History and the Historical Moment. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1982). The Life Cycle Completed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H., & Erikson, J. M. (1997). The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, K. T. (2004). Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Friedman, L. J. (1999). Identity’s Architect: A Biography of Erik H. Erikson. New York: Scribner.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goldstein, E. G. (2001). Object relations theory and self psychology in social work practice. New York: Free Press.

Hoare, C. H. (2002). Erikson on Development in Adulthood: New Insights from the Unpublished Papers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kroger, J. (2004). Identity in adolescence: The balance between self and other. New York: Routledge.

Levinson, D. J. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Ballantine Books.

Logan, R. D. (1986). A reconceptualization of Erikson’s theory: The repetition of existential and instrumental themes. Human Development, 29(3), 125-136.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551-558.

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. Handbook of adolescent psychology, 9(11), 159-187.

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100-122.

Miller, P. H. (2011). Theories of developmental psychology. New York: Worth Publishers.

Muuss, R. E. (1996). Theories of adolescence. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Newman, B. M., & Newman, P. R. (2017). Development through life: A psychosocial approach. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Noam, G. G. (1999). The psychology of belonging: Reformulating adolescent development. Annals of the American Society for Adolescent Psychiatry, 24, 49-68.

Roazen, P. (1976). Erik H. Erikson: The Power and Limits of a Vision. New York: Free Press.

Schaie, K. W., & Willis, S. L. (2015). Handbook of the psychology of aging. London: Academic Press.

Schwartz, S. J. (2001). The evolution of Eriksonian and neo-Eriksonian identity theory and research: A review and integration. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 1(1), 7-58.

Seligman, S., & Shanok, R. S. (1995). Erikson, our contemporary: His anticipation of an intersubjective perspective. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 5(3), 379-405.

Sheehy, G. (1976). Passages: Predictable crises of adult life. New York: E. P. Dutton.

Slater, C. L. (2003). Generativity versus stagnation: An elaboration of Erikson’s adult stage of human development. Journal of Adult Development, 10(1), 53-65.

Sokol, J. T. (2009). Identity development throughout the lifetime: An examination of Eriksonian theory. Graduate Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1(2), 14.

Stevens, R. (2008). Erik Erikson: Explorer of identity and the life cycle. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Vaillant, G. E. (2002). Aging well: Surprising guideposts to a happier life from the landmark study of adult development. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Wallerstein, R. S., & Goldberger, L. (Eds.). (1998). Ideas and Identities: The Life and Work of Erik Erikson. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

Waterman, A. S. (1982). Identity development from adolescence to adulthood: An extension of theory and a review of research. Developmental Psychology, 18(3), 341-358.

Whitbourne, S. K., & Whitbourne, S. B. (2010). Adult development and aging: Biopsychosocial perspectives. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Wrightsman, L. S. (1994). Adult personality development: Theories and concepts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Yufit, R. I. (1969). Variations and groupings in the development of ego identity. Dissertation Abstracts International, 29(9-B), 3500.

Zimmermann, P., & Iwanski, A. (2014). Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(2), 182-194.

Influential Psychologists

0 Comments