Who Was Milton Erickson?

1. The Groundbreaking Legacy of Milton H. Erickson in Psychotherapy

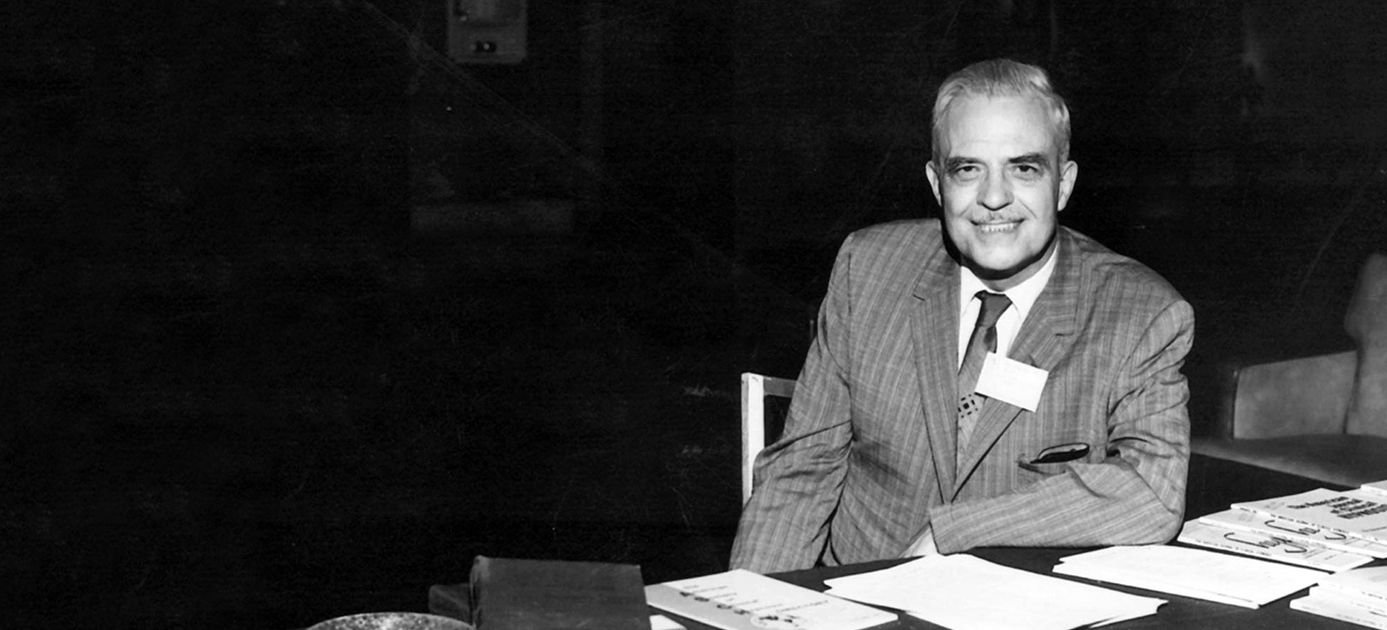

Milton H. Erickson (1901-1980) was one of the most innovative and influential psychotherapists of the 20th century. Best known for his groundbreaking work in hypnosis and strategic psychotherapy, Erickson developed a highly creative, intuitive and individualized approach that departed radically from the dominant psychoanalytic and behavioral models of his time. His unique style of hypnosis, characterized by indirect suggestion, metaphor, and storytelling, came to be known as “Ericksonian hypnosis” and laid the foundation for much of contemporary clinical hypnosis and brief therapy.

Erickson’s contributions extend far beyond the field of hypnosis, however. His deep understanding of unconscious processes, his appreciation for the resourcefulness and uniqueness of each individual, and his ability to utilize any aspect of human experience for therapeutic purposes, have had a profound impact on the theory and practice of psychotherapy as a whole. His influence can be seen in the work of strategic therapists like Jay Haley and Cloe Madanes, the brief solution-focused therapies of Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg, and the neo-Ericksonian approaches of Stephen Gilligan and Jeffrey Zeig, among many others.

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive overview of Erickson’s life and work, tracing the development of his ideas and techniques within the context of his personal history and the intellectual currents of his time. Special attention will be given to Erickson’s unique conceptualization of the unconscious mind, his strategic utilization of symptoms and resistance, and his artistic use of language and communication. The paper will also explore the legacy of Ericksonian approaches in contemporary psychotherapy and the challenges of transmitting Erickson’s highly intuitive and improvisational style to new generations of therapists.

2. Milton Erickson’s Life Journey: From Adversity to Innovation

2.1. Overcoming Challenges: Erickson’s Early Life and Education

Milton Hyland Erickson was born on December 5, 1901 in Aurum, Nevada, a small mining town in the high desert. The second of nine children, Erickson grew up in a tight-knit Mormon family that valued hard work, self-reliance, and practical education. From an early age, Erickson displayed an intense curiosity about the natural world and a keen ability to observe and experiment. He spent much of his childhood exploring the desert landscape, collecting specimens, and conducting his own informal experiments on plants, animals, and minerals.

Erickson’s early life was marked by a series of physical and developmental challenges that would profoundly shape his personal and professional identity. Born color blind and tone deaf, Erickson struggled with dyslexia and other learning difficulties throughout his school years. At age 17, he contracted polio and was left paralyzed and near death. Defying medical predictions, Erickson taught himself to walk again through sheer force of will and careful observation of his baby sister’s movements. The experience of overcoming polio left Erickson with a deep appreciation for the power of the human mind and a lifelong fascination with altered states of consciousness.

After graduating from high school, Erickson enrolled at the University of Wisconsin to study psychology and medicine. He earned his bachelor’s degree in psychology in 1923 and his medical degree in 1928. During his undergraduate years, Erickson began to experiment with hypnosis, conducting informal trance sessions with friends and classmates. He was particularly influenced by the work of Clark Hull, a leading hypnosis researcher who emphasized the role of suggestion and conditioning in trance phenomena.

2.2. Pioneering Ericksonian Hypnosis: Early Career Breakthroughs

After completing his medical training, Erickson opened a private practice in Eloise, Michigan, where he began to develop his unique approach to hypnosis and psychotherapy. Unlike most hypnotists of his time, who relied on authoritarian techniques and direct suggestion, Erickson experimented with more permissive and indirect methods that sought to activate the patient’s own unconscious resources.

Erickson’s approach was heavily influenced by his personal experiences of overcoming physical and psychological adversity. He believed that the unconscious mind was a vast reservoir of learning, creativity and problem-solving capacity that could be harnessed for therapeutic change. Rather than imposing his own agenda or interpretations on patients, Erickson sought to create a climate of acceptance and exploration in which the patient’s own inner wisdom could emerge.

One of Erickson’s key innovations was the use of indirect suggestion and metaphor to bypass conscious resistance and communicate with the unconscious mind. Instead of giving direct commands or instructions, Erickson would often tell stories, jokes or anecdotes that contained embedded suggestions and analogies relevant to the patient’s problem. He might talk about a cactus blooming in the desert to suggest resilience and growth, or describe a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis to evoke images of transformation and change.

Erickson was also a master of utilizing whatever presented itself in the therapy session, from the patient’s body language and verbal expressions to chance events and interruptions. He believed that every aspect of the patient’s experience could be used strategically to promote therapeutic goals. For example, if a patient expressed doubt or resistance, Erickson might paradoxically encourage and even exaggerate the resistance, using it to create a “double bind” that propelled the patient towards change.

Many of Erickson’s early case studies illustrate his creative and unorthodox approach. In one famous case, a woman consulted Erickson for help with chronic insomnia. Instead of directly suggesting sleep, Erickson instructed the woman to stay awake and search her house for “something red and something green” that would capture her interest and imagination. The paradoxical task not only distracted the woman from her sleep difficulties but also activated her curiosity and sense of adventure, leading to a natural trance state and a good night’s sleep.

In another case, Erickson was consulted by a severely alcoholic man who had failed numerous previous treatments. Rather than confronting the man’s drinking directly, Erickson instructed him to sit in front of a large cactus in his yard and “hallucinate vividly” about his drunken binges, going into as much detail as possible. The task not only interrupted the man’s actual drinking but also brought the negative consequences of his addiction into sharp focus, mobilizing his own desire for change.

2.3. Shaping Modern Psychotherapy: Erickson’s Later Career and Global Influence

As Erickson’s reputation grew, he began to attract a wide range of students, colleagues and patients from around the world. In 1948, he moved his practice to Phoenix, Arizona, where he continued to refine his approach and train new generations of therapists. He held informal workshops and seminars at his home, demonstrating his techniques and discussing his cases with a select group of students and collaborators.

Among Erickson’s most influential students were Jay Haley and Ernest Rossi, who went on to publish numerous books and articles disseminating Erickson’s ideas. Haley, in particular, played a key role in bringing Erickson’s work to a wider audience, writing the first major book on Ericksonian hypnosis, “Uncommon Therapy”, in 1973. Haley also incorporated many of Erickson’s ideas into his own strategic approach to family therapy, which emphasized the use of directives, paradox, and reframing to disrupt problematic patterns and promote change.

In his later years, Erickson continued to innovate and experiment, developing new techniques like the “handshake induction” and the “confusion technique” to rapidly induce trance states. He also began to explore the use of hypnosis for pain control, working with cancer patients and other chronic pain sufferers to help them manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life. Despite his own declining health, Erickson remained active and engaged until his death in 1980, leaving behind a vast legacy of teaching, writing, and clinical wisdom.

3. Core Principles of Ericksonian Therapy: Unlocking the Power of the Unconscious Mind

3.1. Harnessing the Unconscious: Erickson’s Unique Perspective

At the heart of Erickson’s approach was a profound respect for the power and creativity of the unconscious mind. Unlike Freud, who saw the unconscious as a repository of primitive drives and repressed conflicts, Erickson viewed it as a positive resource that could be harnessed for growth and change. He believed that the unconscious mind was constantly processing and integrating information from the environment, forming new associations and patterns that could be used to solve problems and overcome obstacles.

For Erickson, the role of the therapist was not to interpret or analyze the unconscious but to create conditions that would allow it to express itself and do its own healing work. He often compared the unconscious to a “self-organizing system” that had its own inherent wisdom and direction. By providing a permissive and supportive environment, the therapist could facilitate the natural unfolding of this inner wisdom, rather than imposing their own agenda or expectations.

Erickson’s view of the unconscious mind was deeply influenced by his studies of hypnosis and altered states of consciousness. He observed that in trance states, people often had access to memories, abilities and experiences that were not available to their ordinary waking consciousness. He saw hypnosis as a way of bypassing the critical, analytical functions of the conscious mind and communicating directly with the unconscious, where profound changes could occur spontaneously and effortlessly.

3.2. The Art of Utilization: Transforming Obstacles into Opportunities

One of Erickson’s most distinctive contributions was his theory of utilization, which held that any aspect of the patient’s experience could be used strategically to promote therapeutic change. Rather than trying to eliminate or counteract symptoms or resistance, Erickson sought to incorporate them into the therapy process, using them as levers for transformation.

For example, if a patient presented with a stubborn symptom like a phobia or compulsion, Erickson might paradoxically prescribe the symptom, instructing the patient to intentionally engage in the feared behavior or thought. By exaggerating and even caricaturing the symptom, Erickson could help the patient gain a new perspective on it, often leading to spontaneous resolution or transformation.

Similarly, if a patient expressed doubt, ambivalence or resistance to change, Erickson would often join with and even amplify the resistance, using it to create a “double bind” that propelled the patient in a new direction. He might say something like, “I know you’re not sure if you’re ready to change, and that’s okay. In fact, I’d like you to take all the time you need to really explore your doubts and hesitations, and only change when you feel absolutely certain that it’s the right thing to do.” By validating the patient’s resistance and making it a precondition for change, Erickson could often bypass it and mobilize the patient’s own motivation and resources.

3.3. Indirect Suggestion and Metaphor: Communicating with the Unconscious

Perhaps the most well-known aspect of Ericksonian hypnosis is the use of indirect suggestion and metaphor to communicate with the unconscious mind. Rather than giving direct commands or instructions, Erickson would often embed his therapeutic messages in stories, anecdotes, or analogies that engaged the patient’s imagination and invited unconscious processing.

For example, instead of telling a patient to relax or let go of anxiety, Erickson might tell a story about a person walking through a forest and discovering a peaceful clearing where they could rest and recharge. The story would be sprinkled with sensory details and hypnotic language patterns designed to evoke a state of deep relaxation and inner calm.

Erickson believed that metaphors and stories were particularly effective because they could bypass the conscious mind’s critical analysis and speak directly to the unconscious. By engaging the patient’s imagination and evoking rich sensory experiences, metaphors could create a kind of “waking dream” state in which new possibilities and perspectives could emerge.

Erickson’s use of metaphor was also highly strategic and tailored to each individual patient. He would often use the patient’s own words, interests and life experiences as raw material for his therapeutic stories, creating a sense of personal relevance and resonance. He might talk about a patient’s favorite hobby or sport, drawing parallels between the skills and attitudes required for success in that area and the resources needed for overcoming a particular problem.

3.4. Rapid Trance Induction: The Confusion Technique and Handshake Method

In his later years, Erickson developed a number of innovative techniques for rapidly inducing trance states and bypassing conscious resistance. Two of the most well-known are the “confusion technique” and the “handshake induction.”

The confusion technique involves overloading the patient’s conscious mind with a barrage of complex, contradictory or irrelevant information, creating a state of mental confusion and disorientation. As the conscious mind tries to make sense of the confusing input, it becomes temporarily suspended, allowing the unconscious to become more receptive to suggestion.

The handshake induction is a technique for inducing trance through a seemingly ordinary social gesture. As the therapist and patient shake hands, the therapist will subtly interrupt the expected pattern of the handshake, perhaps by holding on a bit too long or changing the pressure of their grip. This unexpected disruption can create a momentary state of confusion and dissociation, which the therapist can then use to guide the patient into a deeper trance state.

Both of these techniques reflect Erickson’s fascination with the use of surprise, confusion and destabilization to create therapeutic change. He believed that by disrupting the patient’s habitual patterns and expectations, the therapist could create a kind of “liminal space” in which new possibilities could emerge.

4. The Enduring Impact of Milton Erickson on Modern Psychotherapy

4.1. Challenges in Replicating Erickson’s Intuitive Approach

Despite his enormous influence on modern psychotherapy, Erickson’s highly intuitive and improvisational approach has proven difficult to codify and replicate. Many of his techniques were based on his own extraordinary ability to observe and utilize the subtlest cues and responses from his patients, a skill that was honed over decades of intensive clinical practice.

Erickson himself acknowledged the difficulty of teaching his approach to others, often saying that the best way to learn hypnosis was to “do it and do it and do it.” He emphasized the importance of developing one’s own intuition and flexibility, rather than simply following a set of techniques or scripts.

As a result, many of Erickson’s students and followers have struggled to capture the essence of his approach in a way that can be easily taught or transmitted. While there are now numerous books, workshops and training programs in Ericksonian hypnosis, few have been able to replicate the remarkable results that Erickson himself was able to achieve.

Some have argued that Erickson’s approach was so deeply rooted in his own unique personality and life experiences that it may not be possible or even desirable to try to duplicate it. Others have suggested that the very intuitiveness and spontaneity that made Erickson’s work so powerful may also make it resistant to systematic study and replication.

4.2. Strategic and Systemic Therapies: Erickson’s Influence on Brief Solutions

Despite these challenges, Erickson’s ideas have had a profound impact on the development of strategic and systemic approaches to psychotherapy. His emphasis on using the patient’s own resources and experiences, his strategic use of directives and paradoxical interventions, and his appreciation for the role of context and relationship in change processes, have all become core principles of these approaches.

In particular, Erickson’s work has been a major influence on the development of brief solution-focused therapies, such as those pioneered by Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg. These approaches share Erickson’s emphasis on utilizing the patient’s strengths and resources, setting clear and achievable goals, and using the therapy process itself as a catalyst for change.

Erickson’s ideas have also been influential in the development of narrative and postmodern approaches to therapy, which emphasize the role of language and storytelling in shaping individual and social realities. Like Erickson, these approaches view problems and solutions as socially constructed and seek to create new meanings and possibilities through the use of metaphor, reframing, and collaborative dialogue.

4.3. The Neo-Ericksonian Movement: Expanding Erickson’s Vision

In recent years, a new generation of therapists and researchers have sought to build on Erickson’s legacy and expand the boundaries of Ericksonian hypnosis. Sometimes referred to as the “neo-Ericksonian” tradition, this movement includes figures like Stephen Gilligan, Jeffrey Zeig, and Ernest Rossi, who have sought to integrate Erickson’s ideas with contemporary developments in neuroscience, phenomenology, and mind-body medicine.

One of the key themes of the neo-Ericksonian tradition is the importance of the therapist’s own state of consciousness and presence in the therapy process. Drawing on Erickson’s own emphasis on the “self-hypnotic” nature of therapeutic trance, these approaches view the therapist’s own state of focus, attunement and creativity as crucial factors in inducing change.

Another important development in the neo-Ericksonian tradition has been the exploration of the social and relational dimensions of hypnosis and therapy. While Erickson himself tended to focus on individual change processes, contemporary Ericksonian therapists have become increasingly interested in the ways that trance states and therapeutic interventions are shaped by the larger social and cultural context.

Finally, the neo-Ericksonian tradition has been marked by a renewed emphasis on the spiritual and transpersonal dimensions of hypnosis and healing. Drawing on Erickson’s own deep respect for the wisdom and creativity of the unconscious mind, these approaches view trance states as potential gateways to a wider realm of consciousness and meaning.

5. Conclusion: Milton Erickson’s Transformative Vision for Mental Health and Healing

Milton Erickson’s life and work continue to inspire and challenge therapists and researchers around the world. His unique approach to hypnosis and psychotherapy, characterized by indirection, utilization, and a deep respect for the individual’s own resources and creativity, has had a profound impact on the development of strategic, systemic, and brief therapies. At the same time, Erickson’s highly intuitive and improvisational style has proven difficult to codify and replicate, leading to ongoing debates about the nature and limits of his approach.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of Erickson’s work is his vision of the unconscious mind as a positive and generative force, possessing a wisdom and creativity that far exceeds our conscious understanding. For Erickson, the goal of therapy was not to impose external solutions or interpretations, but to create a space of safety and possibility in which the individual’s own inner resources could be accessed and utilized.

This vision continues to inspire new generations of therapists and researchers, who are exploring the frontiers of hypnosis, neuroscience, and mind-body medicine. While the specific techniques and strategies may vary, the core principles of Ericksonian therapy – respect for the individual, utilization of resources, and trust in the healing power of the unconscious – remain as vital and relevant as ever.

As we face the challenges and complexities of the 21st century, Erickson’s legacy reminds us of the importance of creativity, flexibility, and a deep appreciation for the mysteries of the human mind. By embracing these qualities in our own lives and work, we may discover new possibilities for healing and transformation, both for ourselves and for the world around us.

6. References

Bandler, R., & Grinder, J. (1975). Patterns of the Hypnotic Techniques of Milton H. Erickson, M.D. Cupertino, CA: Meta Publications.

Erickson, M. H. (1980). The Collected Papers of Milton H. Erickson on Hypnosis (4 vols.). New York: Irvington.

Erickson, M. H., & Rossi, E. L. (1979). Hypnotherapy: An Exploratory Casebook. New York: Irvington.

Erickson, M. H., & Rossi, E. L. (1981). Experiencing Hypnosis: Therapeutic Approaches to Altered States. New York: Irvington.

Gilligan, S. G. (1987). Therapeutic Trances: The Cooperation Principle in Ericksonian Hypnotherapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Haley, J. (1973). Uncommon Therapy: The Psychiatric Techniques of Milton H. Erickson, M.D. New York: Norton.

Rosen, S. (Ed.). (1982). My Voice Will Go With You: The Teaching Tales of Milton H. Erickson. New York: Norton.

Rossi, E. L. (Ed.). (1980). The Collected Papers of Milton H. Erickson on Hypnosis (4 vols.). New York: Irvington.

Zeig, J. K. (Ed.). (1982). Ericksonian Approaches to Hypnosis and Psychotherapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Zeig, J. K., & Geary, B. B. (Eds.). (2000). The Handbook of Ericksonian Psychotherapy. Phoenix, AZ: The Milton H. Erickson Foundation Press.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Influential Psychologists

0 Comments