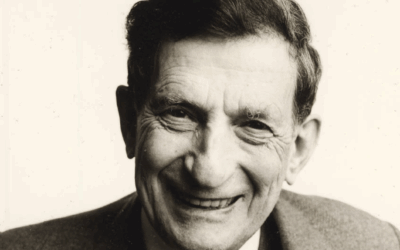

The Biologist of the Unconscious

For much of the 20th century, depth psychology and evolutionary biology were enemies. Biology viewed the mind as a machine for survival, while psychology viewed it as a realm of meaning and symbol. Anthony Stevens (1933–2021) was the man who ended the war.

A psychiatrist and Jungian analyst, Stevens argued that archetypes are not mystical concepts floating in the ether; they are biological imperatives wired into our DNA. He called them “phylogenetic neuropsychic centers.” Just as we are born with the physical potential to grow legs and lungs, we are born with the psychological potential to become a Mother, a Hero, or a Wise Old Man. His work grounds the spiritual insights of Carl Jung in the hard science of ethology and neuroscience.

Biography & Timeline: Anthony Stevens

Born in Plymouth, England, Stevens studied psychology at Reading University and medicine at Oxford. This dual training—in the subjective mind and the objective body—defined his career. He trained as an analyst with the Independent Group of Analytical Psychologists (IGAP) in London.

Stevens was deeply influenced by John Bowlby (attachment theory) and Niko Tinbergen (ethology). He realized that Jung’s “archetypes” were identical to what biologists called “innate releasing mechanisms.” This insight led to his groundbreaking book, Archetype: A Natural History of the Self (1982), which remains the standard text on evolutionary Jungian psychology.

Key Milestones in the Life of Anthony Stevens

| Year | Event / Publication |

| 1933 | Born in Plymouth, England. |

| 1960s | Trains in medicine at Oxford; begins psychiatric practice. |

| 1982 | Publishes Archetype: A Natural History of the Self. |

| 1993 | Publishes The Two Million-Year-Old Self. |

| 1995 | Publishes Private Myths: Dreams and Dreaming. |

| 2021 | Dies, leaving a legacy of scientific rigor in depth psychology. |

Major Concepts: The Archetype as Biological Necessity

The Two Million-Year-Old Self

Stevens argued that modern neurosis stems from a mismatch between our ancient biology and our modern environment. We have a “Two Million-Year-Old Self” that expects to live in a small tribe, surrounded by nature, with clear rites of passage. When modern life fails to provide these conditions, the archetypes (the built-in programs for living) misfire, causing depression and anxiety.

Archetypes as “Innate Releasing Mechanisms”

Drawing on ethology, Stevens explained archetypes as biological programs that lie dormant until triggered by the environment.

Example: A baby is born with the potential to bond (the Mother Archetype). When the baby sees a face and feels warmth, this archetype is “released,” and the bonding behavior begins. If the environment fails to trigger the archetype, the potential withers, leading to pathology.

The Archetypal Stages of Life

Stevens mapped the life cycle not just as a social progression, but as a biological unfolding of specific archetypes:

- Infancy: The Mother/Child dyad (Attachment).

- Youth: The Hero/Warrior (Exploration and Status).

- Maturity: The Father/Mother (Provision and Care).

- Old Age: The Wise Elder (Reflection and Meaning).

Trauma occurs when a person gets “stuck” in a stage because the transition ritual was missing or the archetype was overwhelmed.

The Conceptualization of Trauma: Frustrated Archetypal Intent

For Stevens, trauma is Frustrated Archetypal Intent. The psyche wants to develop. It has a blueprint for wholeness (Individuation). Trauma blocks this blueprint.

The “Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness” (EEA)

Stevens used Bowlby’s concept of the EEA to explain modern suffering. Our brains evolved for the EEA (the Pleistocene savannah). In the EEA, trauma was usually physical and acute (a lion attack). In the modern world, trauma is chronic and social (loneliness, meaningless work). Our archetypal defenses—like the fight-flight response—are constantly triggered but never resolved, leading to PTSD and chronic stress.

Legacy: The Scientific Jungian

Anthony Stevens saved Jungian psychology from becoming a purely mystical cult. He gave it scientific legs to stand on. Today, his work is foundational for fields like Neuropsychoanalysis and Evolutionary Psychology.

For the therapist, Stevens offers a powerful reframing: the client’s symptoms are not mistakes; they are ancient biological programs trying to function in a world that no longer makes sense.

Bibliography

- Stevens, A. (1982). Archetype: A Natural History of the Self. Routledge.

- Stevens, A. (1993). The Two Million-Year-Old Self. Texas A&M University Press.

- Stevens, A. (1995). Private Myths: Dreams and Dreaming. Harvard University Press.

- Stevens, A., & Price, J. (1996). Evolutionary Psychiatry: A New Beginning. Routledge.

0 Comments