Confronting the Shadow of Mental Health Challenges

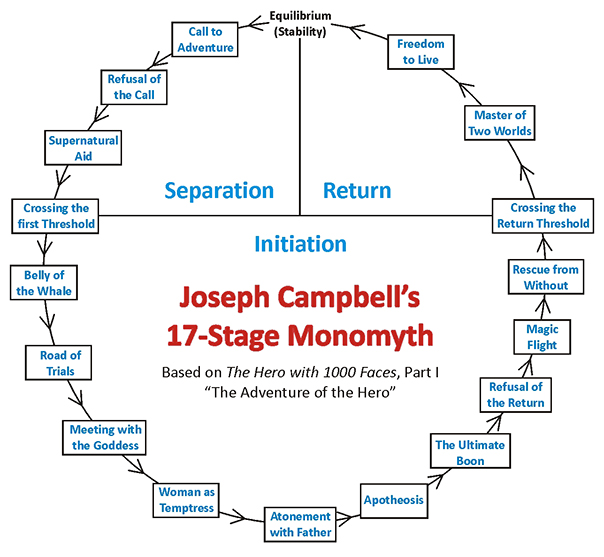

The hero’s journey is a powerful narrative structure that has shaped storytelling across cultures and throughout history. First articulated by mythologist Joseph Campbell, the hero’s journey follows a protagonist’s transformative quest to overcome challenges and emerge victorious. This archetypal story arc has profoundly influenced literature, film, and even the practice of psychotherapy, providing a framework for understanding personal growth and the confrontation with our inner demons.

Main Points and Key Ideas:

- The hero’s journey is a powerful narrative structure that has shaped storytelling across cultures and throughout history.

- Carl Jung saw the hero’s journey as a metaphor for the process of individuation and integrating the conscious and unconscious selves.

- A key stage in the hero’s journey is confronting the shadow – the dark, repressed aspects of the psyche.

- The “villain as mirror” motif appears in many mythological and literary examples, reflecting disowned parts of the self.

- Mental health challenges like ADHD, PTSD, and addiction can be viewed through the lens of the hero’s journey and shadow work.

- The path to healing often involves integrating and transforming the “villainous” aspects of the self rather than eliminating them.

- The hero’s journey aligns with cognitive science principles like acceptance, schemas, and self-efficacy.

- Many therapeutic modalities have incorporated themes from the hero’s journey, including narrative therapy and Jungian analysis.

- The hero’s journey has had a significant impact on screenwriting and film structure.

- Campbell distinguished between “left-hand path” myths of individual quests and “right-hand path” myths emphasizing social norms.

- Religious figures like Moses, Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad can be viewed through the lens of the hero’s journey.

- Social and political activists like Gandhi, King, and Mandela embodied aspects of the hero’s journey in their work.

- The 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous reflect the stages of the hero’s journey applied to addiction recovery.

- Bill Wilson, AA’s founder, was influenced by Carl Jung’s ideas about the spiritual dimensions of addiction.

- The hero’s journey provides a framework for understanding personal and social transformation across many contexts.

The History of the Hero’s Journey in Jungian Thought

The concept of the hero’s journey is deeply rooted in the work of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung. Jung believed that myths and fairy tales contained universal symbols and themes that reflect the collective unconscious – the shared ancestral memories and experiences of humankind. He saw the hero’s journey as a metaphor for the process of individuation, in which an individual integrates their conscious and unconscious selves to achieve wholeness and self-realization.

A key stage in the hero’s journey is the confrontation with the shadow – the dark, repressed aspects of the psyche that we deny or project onto others. Jung believed that facing and integrating the shadow was essential for psychological growth and maturity. In myths and stories, this often takes the form of the hero battling a villain or monster that embodies their deepest fears and weaknesses. By overcoming this adversary, the hero discovers hidden strengths and achieves a new level of self-awareness.

Healing with the Heroes Journey

This theme appears across many mythological and literary examples. In the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, the wild man Enkidu begins as Gilgamesh’s rival but becomes his greatest friend and alter-ego. In the Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna must overcome his attachments and aversions to see his enemies as extensions of the Divine. And in the Harry Potter series, Harry’s nemesis Voldemort is gradually revealed to be intimately linked to Harry himself, a dark reflection of his own hidden powers and unresolved trauma.

Psychologically, we can see this “villain as mirror” motif play out in many common mental health challenges:

In ADHD, the restless, impulsive energy that sabotages focus and follow-through can, when channeled constructively, become a source of creativity, spontaneity, and entrepreneurial spirit. The hero’s task is to befriend and harness this misunderstood energy rather than fighting it.

In PTSD, the disturbing flashbacks, nightmares, and hypervigilance are not just symptoms to eradicate, but messages from a wounded part of the psyche that needs attention, compassion, and integration. The traumatized “villain” needs to be heard, validated, and brought into the light of self-understanding.

And in psychological trauma more broadly, the coping mechanisms and defensive postures that once protected the vulnerable self can calcify into self-limiting patterns that perpetuate suffering. Healing involves recognizing these “villainous” behaviors as misguided attempts to maintain safety, and reparenting these fragmented parts of the self with wisdom and love.

In each case, the path to wholeness is not to eliminate the villain, but to transform the villain through integration. As Jung said, “I’d rather be whole than good.” The hero’s journey invites us to expand our self-concept to include those aspects we fear, judge, or reject in ourselves. It’s a movement from dualistic opposition to the paradoxical union of light and shadow, hero and adversary.

Like the compassionate Buddha extending a hand to the demon Mara, or Christ breaking bread with Judas, we discover that the villain is not an enemy to be defeated but a lost part of ourselves to be reclaimed and redeemed. This is the sacred marriage at the heart of the hero’s journey – the alchemical union of opposites in the crucible of self-awareness and radical self-acceptance.

Seen in this light, the hero’s journey becomes a wellspring of hope and healing for those wrestling with their inner demons. It reminds us that our darkest, most painful material can become the prima materia for the magnum opus – the great work of fashioning our most authentic, vibrant and liberated self. What a profound act of imagination and mercy, to befriend our inner villains until they become, at last, our most intimate allies.

The Hero’s Journey in Mythology

Mythological tales across cultures feature heroes who embark on perilous quests and confront fearsome foes. In Greek myth, Odysseus undergoes an epic journey home after the Trojan War, facing dangers like the Cyclops and the Sirens. In doing so, he must also battle his inner weaknesses of pride and infidelity.

The ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh follows a king who seeks immortality after the death of his beloved friend Enkidu. Gilgamesh’s quest leads him to confront his fear of death and the limits of his power. By accepting his mortality, he is able to let go of his hubris and find meaning in life.

These mythic tales illustrate universal human struggles and the transformative power of facing one’s shadow. They provide enduring inspiration and wisdom for navigating life’s challenges.

The Shadow of Mental Health: ADHD, PTSD and Addiction

In a psychotherapeutic context, the hero’s journey provides a powerful lens for understanding mental health challenges like ADHD, PTSD, and addiction. These conditions can be seen as the shadow – the disowned parts of the self that create inner conflict and suffering.

For someone with ADHD, the shadow may manifest as a sense of inadequacy or shame about their struggles with focus and organization. They may feel like they are constantly battling a villain of distraction and impulsivity. However, by reframing their journey, they can come to see their ADHD as a source of unique strengths – like creativity, spontaneity, and the ability to make intuitive connections that others miss. They are heroes trying to manage the many demands and stimuli of a neurotypical world, not immature or stupid.

Similarly, someone with PTSD must confront the shadow of their trauma – the painful memories, emotions and beliefs that haunt them. Like a mythological hero descending into the underworld, they must navigate the dark labyrinth of their psyche to find healing and renewal. With the support of a skilled therapist (a “wise old man or woman” archetype), they can reprocess traumatic experiences, challenge distorted beliefs, and emerge with a new sense of strength and wholeness.

For those struggling with addiction, the shadow takes the form of the compulsive drive to seek relief in substances or behaviors, despite destructive consequences. Recovery is a hero’s journey of facing the underlying pain, insecurities and existential fears that fuel addiction. By excavating the shadow, they can reclaim disowned aspects of themselves and build a new identity founded on self-awareness and self-compassion.

Cognitive Science First Principles: Acceptance, Schemas, and Self-Efficacy

The hero’s journey model aligns with several key principles from cognitive science and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

One core tenet is the importance of accepting external realities that cannot be changed, while focusing on adjusting one’s inner world. Rather than obsessing about limitations or injustices in the outer world, the hero must confront and transform their own perceptions, beliefs and responses. This principle is central to acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which encourages psychological flexibility – the ability to fully experience the present moment, while engaging in committed action toward one’s values.

The hero’s journey also reflects the cognitive science concept of schemas – the mental frameworks or “maps” we use to organize information and make sense of the world. Our schemas are shaped by our experiences, and they influence how we perceive, interpret and remember events. Maladaptive schemas, often developed in response to adverse childhood experiences, can contribute to mental health problems by generating distorted or overly negative perceptions.

In the hero’s journey, the “Ordinary World” often represents the hero’s existing schemas – the assumptions and beliefs that have guided them thus far. The journey challenges these schemas, forcing the hero to expand their understanding and adopt new ways of seeing themselves and the world. Cognitive therapies likewise help patients become aware of their schemas and develop more adaptive and flexible ways of thinking.

Another key principle is self-efficacy – the belief in one’s ability to face challenges and achieve goals. Bandura’s social cognitive theory posits that self-efficacy is a key determinant of motivation, affect and behavior. When we believe we can succeed, we are more likely to persevere in the face of obstacles and bounce back from failures.

The hero’s journey is fundamentally a story of developing self-efficacy. At the beginning, the hero often doubts their abilities and feels inadequate to the task. But through facing trials, learning from mentors, and discovering inner resources, they grow in confidence and competence. Each victory, however small, increases the hero’s sense of self-efficacy, preparing them for greater challenges ahead.

Therapeutic approaches like cognitive-behavioral therapy and narrative therapy aim to boost self-efficacy by helping patients recognize and build on their strengths, reframe past successes, and develop coping skills for managing distress.

Expressive and creative arts therapies provide opportunities for mastery experiences that enhance self-efficacy in a safe and supportive context.

Neuroscience research suggests that the hero’s journey narrative may have powerful effects on the brain. Studies have found that reading or watching stories activates neural networks involved in empathy, emotion, and social cognition. Compelling narratives engage the brain’s reward system, reinforcing the lessons conveyed. The hero’s journey, with its timeless themes of struggle and triumph, may be especially effective at promoting beneficial neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to form new connections in response to learning and experience.

Therapeutic Modalities and the Hero’s Journey

Many therapeutic modalities have incorporated the language and themes of the hero’s journey. Narrative therapy helps clients “re-author” their life stories, casting themselves as the heroes rather than the victims of their circumstances. Jungian analysis focuses on shadow work and symbolic exploration of the unconscious through dream analysis and creative expression.

In acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), clients are encouraged to embrace difficult thoughts and feelings as part of being human, while committing to living according to their values – embarking on a hero’s journey of living with integrity and purpose despite hardship. Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy evokes the “inner journey” of mythology, with the client as the hero exploring the depths of their consciousness to find healing and self-discovery.

The Hero’s Journey in Screenwriting

The hero’s journey has had an enormous impact on contemporary screenwriting. Many of the most successful and beloved films of all time consciously follow this narrative structure, from Star Wars to The Matrix to The Lion King. Screenwriters often use Campbell’s stages of the monomyth as a template for plot and character development.

In a typical “hero’s journey” film, the protagonist starts out in the Ordinary World of their everyday life, before receiving a Call to Adventure that thrusts them into a Special World of excitement and danger. They may initially Refuse the Call out of fear or insecurity, before meeting a Mentor who gives them the wisdom and tools they need. Crossing the First Threshold, they enter the Special World, where they face Tests, make Allies and confront Enemies.

The Approach to the Inmost Cave represents the hero’s preparation for their greatest challenge, which they then face in the Supreme Ordeal – an all-or-nothing battle or crisis that pushes them to the brink of death or failure. Emerging victorious, they Seize the Sword – a reward or elixir that fulfills the quest. But the journey is not over – they must still make the Road Back to the Ordinary World, often with vengeful forces in pursuit.

The climactic Resurrection is a final test of all the hero has learned, before they can finally Return with the Elixir – the boon or treasure that heals and transforms the Ordinary World. This final stage represents the reintegration of the two worlds, as the hero shares their hard-won wisdom for the betterment of all.

Real World Applications for Mythological Frameworks

In therapy as in mythology, we are all heroes with a thousand faces, each on our own journey of healing and self-discovery. By sharing our stories and supporting each other along the way, we can harness the timeless power of the monomyth and find the inspiration we need to thrive. The hero’s journey gives us hope that no matter how dark the shadow, there is always a path to the light.Understanding its key elements and variations can help us to better navigate our own paths of growth and to appreciate the perennial wisdom embedded in stories.

Context and Applications of Campbell’s Ideas:

Campbell’s concepts have found wide application in fields such as literature, film, psychology, and personal development. Hollywood screenwriters, for example, have used the hero’s journey as a template for crafting memorable characters and plot structures, from Star Wars to The Matrix. In the realm of personal growth, the journey provides a roadmap for navigating life transitions, career changes, and spiritual awakenings.

Psychologists and therapists have also found Campbell’s ideas useful in helping clients reframe their challenges as opportunities for growth and self-discovery. By viewing one’s life through the lens of the journey, individuals can find greater meaning and purpose in their struggles, while also developing the resilience needed to overcome them.

Advertising and sales professionals have also leveraged the power of archetypes and the journey structure to create compelling brand narratives and customer experiences. By positioning a product or service as a “magic elixir” that can transform the customer’s world, marketers tap into deep-seated desires for growth, empowerment and belonging.

Left-Hand vs. Right-Hand Path Myths:

Campbell distinguished between two types of hero’s journeys: the “left-hand path” of the individual quest for self-discovery, and the “right-hand path” of adherence to social norms and roles. Left-hand path myths, such as the Buddha’s journey to enlightenment or Dante’s descent into the underworld, affirm the value of breaking with convention to pursue a higher truth. They reinforce the idea that growth requires leaving the familiar behind and confronting the unknown.

In contrast, right-hand path myths, such as the medieval Grail legends or Confucian parables, emphasize the importance of fulfilling one’s social duties and upholding the status quo. They caution against the dangers of hubris and the pursuit of individual glory at the expense of the collective good.

In the context of therapy, right-hand path myths can be seen as analogous to the deflections and rationalizations that patients use to resist change. Just as these stories justify staying within the bounds of the familiar, clients may cling to limiting beliefs or behavioral patterns out of fear of the unknown. They may tell themselves that they are “not ready” to change, that they need to “be realistic” or that they have no choice but to accept their lot in life.

Therapists can use the hero’s journey framework to challenge these resistances and to reframe the client’s struggles as a necessary part of the growth process. By pointing out the parallels between the client’s situation and left-hand path myths, the therapist can help to normalize feelings of fear and uncertainty while also instilling a sense of purpose and direction.

Mythological Examples:

Left-Hand Path:

- Prometheus stealing fire from the gods to give to humanity

- The Buddha renouncing his princely status to seek enlightenment

- Arjuna’s existential crisis on the battlefield in the Bhagavad Gita

- Jesus challenging religious authorities and social hierarchies

Right-Hand Path:

- Arjuna being convinced to fulfill his duty as a warrior

- Aeneas following his destiny to found Rome, despite his love for Dido

- Chinese folk heroes like Hua Mulan who exemplify filial piety and loyalty

- Percival’s initial failure in the Grail quest due to not asking the right questions

In each of these examples, the hero faces a choice between following their individual path or conforming to societal expectations. The left-hand path heroes choose the former, embracing the challenges of growth and self-actualization, while the right-hand path heroes choose the latter, prioritizing duty, stability and the greater good.

Ultimately, both types of journeys have value and can lead to meaningful outcomes. The key is to recognize when one is being called to embark on a left-hand path journey of individuation, and to find the courage to answer that call. At the same time, the right-hand path reminds us that we are part of a larger web of relationships and responsibilities, and that our actions have consequences beyond ourselves.

By deeply engaging with these mythic patterns and their psychological implications, we can gain a richer understanding of the human condition and the myriad ways in which we make meaning of our lives. The hero’s journey, in all its variations, remains a powerful tool for self-discovery and transformation, as relevant today as it was in the ancient world.

The Hero’s Journey in Religious History

In the history of religion, the hero’s journey can be seen as a template for the lives of key figures such as:

- Moses

- Buddha

- Jesus

- Muhammad

These spiritual leaders all underwent journeys of exile, trial, and transformation before returning to their communities with a new vision of the divine. Their stories of spiritual heroism have inspired countless generations of believers and have shaped the mythology and practices of major faith traditions, including:

- Judaism

- Buddhism

- Christianity

- Islam

Moreover, the stages of the hero’s journey – such as the call to adventure, the road of trials, and the return with the elixir – can be mapped onto the development of religious movements themselves, providing a powerful framework for understanding the challenges and opportunities of spiritual transformation.

The Hero’s Journey in Social and Political Change

In the realm of social and political change, the hero’s journey can be seen in the stories of iconic activists, revolutionaries, and reformers, such as:

- Mahatma Gandhi

- Martin Luther King Jr.

- Nelson Mandela

These legendary figures all underwent personal journeys of sacrifice and struggle before emerging as leaders of their respective movements, such as:

- The Indian independence movement

- The civil rights movement

- The anti-apartheid movement

The stages of the hero’s journey can also be applied to the trajectory of social movements themselves, from the initial call to adventure to the final return with the elixir of transformative change. By studying these movements through the lens of the monomyth, we can better understand the psychological and mythic dimensions of social change and the role that individual heroism plays in collective liberation.

Key Takeaways

The hero’s journey is a valuable tool for making sense of the challenges and opportunities of personal and social transformation.

By recognizing the archetypal patterns that shape our lives and our world, we can tap into the wisdom of myth and the power of the human spirit in our efforts to create positive change.

While the hero’s journey is not a one-size-fits-all template, it remains a powerful framework for understanding the universal human experiences of struggle, growth, and transformation.

The Heroes Journey in AA Alcoholics Anonymous

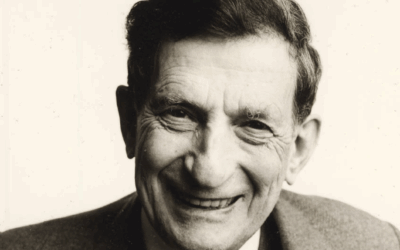

Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), had a profound experience that shaped the development of the program and its emphasis on the hero’s journey narrative. In 1931, Wilson was hospitalized for his alcoholism and was under the care of Dr. William Duncan Silkworth. Despite his best efforts, Wilson was unable to overcome his addiction through medical treatment alone.

During this time, Wilson had a spiritual awakening that he described as a “hot flash” of white light, accompanied by a feeling of ecstasy and a sense of divine presence. This experience convinced Wilson that alcoholism was not just a physical or psychological problem, but a spiritual one as well.

Bill Wilson and Carl Jung

Seeking to understand the nature of his experience, Wilson wrote to Carl Jung, the famous Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst whose work had been a major influence on Joseph Campbell’s conception of the hero’s journey. Wilson had heard that Jung had treated a wealthy American businessman, Rowland Hazard, for alcoholism, and he was curious about Jung’s approach.

Jung wrote back to Wilson, explaining that he had indeed treated Hazard, but that the treatment had ultimately been unsuccessful. Jung believed that Hazard’s alcoholism was a symptom of a deeper spiritual crisis, and that the only solution was a profound spiritual transformation.

In his letter to Wilson, Jung wrote:

“His craving for alcohol was the equivalent, on a low level, of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in medieval language: the union with God.”

Jung went on to say that this spiritual thirst could not be satisfied by human means alone, but required a surrender to a higher power:

“I am strongly convinced that the evil principle prevailing in this world leads the unrecognized spiritual need into perdition if it is not counteracted either by a real religious insight or by the protective wall of human community. An ordinary man, not protected by an action from above and isolated in society, cannot resist the power of evil, which is called very aptly the Devil. But the use of such words arouses so many mistakes that one can only keep aloof from them as much as possible.”

For Wilson, Jung’s words resonated deeply with his own experience and confirmed his belief that alcoholism was a spiritual disease that required a spiritual solution. Wilson went on to develop the 12 steps of AA, which emphasize the need for surrender to a higher power and the importance of spiritual transformation in the recovery process.

The 12 steps, with their emphasis on self-reflection, confession, amends, and service to others, can be seen as a modern version of the hero’s journey, guiding the individual through the challenges of addiction and into a new life of meaning and purpose.

Jung’s influence on AA is often overlooked, but it was significant. His ideas about the spiritual dimensions of addiction and the need for a transformative experience of surrender and renewal shaped Wilson’s understanding of alcoholism and informed the development of the 12-step program.

Moreover, Jung’s archetypal psychology, with its emphasis on universal patterns of human experience and the power of myth and symbol, provided a theoretical foundation for the hero’s journey narrative that is implicit in the AA program.

While Wilson did not use the language of the hero’s journey explicitly, the parallels between the 12 steps and the stages of the monomyth are clear. By offering a roadmap for spiritual transformation and a supportive community of fellow travelers, AA taps into the same archetypal power that has inspired hero tales throughout history.

In this sense, Wilson can be seen as a modern hero of sorts, one who answered the call to adventure and returned with the elixir of recovery and spiritual awakening. By sharing his own journey and creating a program that has helped millions of others to find their own path to healing, Wilson embodied the timeless role of the hero as a bringer of wisdom and a catalyst for change.

As Jung recognized, the journey of recovery is ultimately a spiritual one, requiring a surrender of the ego and an openness to a power greater than oneself. By integrating this understanding into the AA program, Wilson created a powerful tool for transformation that continues to inspire and guide countless individuals on their own heroic journeys.

The Hero’s Journey in AA

1. The Ordinary World:

The alcoholic is trapped in a world of addiction, denial, and despair. This is the “ordinary world” of the hero’s journey, where the individual is living a life that is out of alignment with their true potential.

2. The Call to Adventure:

The alcoholic experiences a moment of clarity or “hitting bottom,” which serves as a wake-up call and a summons to embark on a journey of recovery. This is the “call to adventure” in the hero’s journey.

3. Refusal of the Call:

Many alcoholics initially resist the call to change, denying the severity of their problem or believing that they can control their drinking on their own. This is the “refusal of the call” in the hero’s journey.

4. Meeting the Mentor:

The alcoholic seeks help from AA or another support group, where they encounter a sponsor or mentor who has already walked the path of recovery. This is the “meeting the mentor” stage in the hero’s journey.

5. Crossing the Threshold:

The alcoholic makes the decision to fully commit to the program of recovery, surrendering their ego and admitting their powerlessness over alcohol. This is the “crossing the threshold” stage in the hero’s journey.

6. Tests, Allies, and Enemies:

The alcoholic faces a series of challenges and temptations as they work the 12 steps and navigate the early stages of sobriety. They must confront their own inner demons (the “enemies”) while also building a support network of fellow recovering alcoholics (the “allies”). This is the “tests, allies, and enemies” stage in the hero’s journey.

7. The Ordeal:

The alcoholic undergoes a profound inner transformation as they work through the 12 steps, confronting their past wrongs, making amends, and surrendering to a higher power. This is the “ordeal” stage in the hero’s journey, where the hero faces their greatest fear and emerges transformed.

8. The Reward:

As a result of working the program, the alcoholic experiences a spiritual awakening and a newfound sense of serenity, courage, and wisdom. This is the “reward” stage in the hero’s journey.

9. The Road Back:

The alcoholic continues to practice the principles of AA in all their affairs, carrying the message of recovery to other alcoholics and serving as a mentor to newcomers. This is the “road back” stage in the hero’s journey, where the hero returns to the ordinary world with the elixir of hard-won wisdom.

10. The Resurrection:

The alcoholic experiences a “daily reprieve” from addiction, contingent on the maintenance of their spiritual condition. Each day brings new challenges and opportunities for growth, requiring the alcoholic to continually recommit to the journey of recovery. This is the “resurrection” stage in the hero’s journey, where the hero faces a final test of their transformation.

11. The Return with the Elixir:

By living the principles of AA and carrying the message of recovery to others, the alcoholic becomes a source of hope and healing for their community. They have returned with the “elixir” of sobriety and spiritual awakening, which they can now share with others who are still struggling.

The Power of Myth in Recovery

By tapping into the archetypal power of the hero’s journey, AA offers a compelling narrative framework for understanding and overcoming addiction. The 12 steps provide a roadmap for the journey of transformation, while the fellowship of AA offers a supportive community of fellow travelers.

Moreover, by emphasizing the role of a “higher power” in the recovery process, AA connects the individual journey of the alcoholic to a larger spiritual narrative of redemption and grace. This mythic dimension of the program has been a key factor in its success and enduring appeal.

Of course, AA is not the only path to recovery, and not everyone will resonate with its particular spiritual language or approach. However, the underlying structure of the hero’s journey – the call to adventure, the road of trials, the ultimate boon of transformation – is a universal one that can be adapted to many different contexts and belief systems.

Ultimately, the power of the hero’s journey lies in its ability to provide a sense of meaning and purpose to the challenges of life, and to offer hope in the face of even the darkest of struggles. By recognizing the ways in which our own stories are shaped by these timeless archetypes, we can find the courage and the inspiration to embark on our own journeys of growth and transformation.

As Bill Wilson and the other founders of AA recognized, the path of recovery is not an easy one, but it is a heroic one. By embracing the call to adventure and committing ourselves to the journey of self-discovery and service to others, we can tap into a deep well of strength and resilience, and find our way back to wholeness and healing.

Bibliography:

1. Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York: Pantheon Books.

2. Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

3. Alcoholics Anonymous. (2001). Alcoholics Anonymous, 4th Edition. New York: A.A. World Services, Inc.

4. Wilson, B. (1988). The Language of the Heart: Bill W’s Grapevine Writings. New York: The AA Grapevine, Inc.

5. Vogler, C. (2007). The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Further Reading:

1. Edinger, E. F. (1992). Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Boston: Shambhala.

2. Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. New York: Harper & Row.

3. May, R. (1991). The Cry for Myth. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

4. Pearson, C. S. (1991). Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World. New York: HarperOne.

5. Armstrong, K. (2005). A Short History of Myth. Edinburgh: Canongate.

6. Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

7. Campbell, J. (1988). The Power of Myth. New York: Doubleday.

8. Booker, C. (2004). The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. London: Continuum.

9. Cousineau, P. (1990). The Hero’s Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work. New York: Harper & Row.

10. Gilligan, S. (2002). The Courage to Love: Principles and Practices of Self-Relations Psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

11. Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. New York: Hyperion.

12. Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

13. McAdams, D. P. (1993). The Stories We Live By: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self. New York: Guilford Press.

14. Murdock, M. (1990). The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness. Boston: Shambhala.

15. O’Connor, P. (2018). The Hero’s Journey Demystified: A Practical Guide to Life Transformation. Seattle: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

16. Rohr, R. (2011). Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

17. Siegel, D. J. (2010). Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation. New York: Bantam.

18. Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.

19. Whitfield, C. L. (1987). Healing the Child Within: Discovery and Recovery for Adult Children of Dysfunctional Families. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications.

20. Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

21. Zoja, L. (1989). Drugs, Addiction and Initiation: The Modern Search for Ritual. Boston: Sigo Press.

22. Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press.

23. Grof, S. (1985). Beyond the Brain: Birth, Death, and Transcendence in Psychotherapy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

24. Hollis, J. (1993). The Middle Passage: From Misery to Meaning in Midlife. Toronto: Inner City Books.

25. Johnson, R. A. (1991). Owning Your Own Shadow: Understanding the Dark Side of the Psyche. New York: HarperOne.

0 Comments