part 1: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-villain-with…nd-screenwriting/

part 2: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/using-jungian-ps…d-fiction-part-2/

part 3: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/applying-jungian…onality-theories/

Read More on Jung here:

How do you Write a Villain?

In the realm of storytelling, villains serve as the embodiment of the hero’s greatest challenges and fears. They are the immovable force that the protagonist must overcome to complete their journey and emerge transformed. However, the concept of the villain is not limited to the pages of a script or the silver screen; it is a powerful metaphor for the psychological shadow that we all must confront within ourselves.

Key Points and Main Ideas:

- Villains in storytelling serve as embodiments of the hero’s greatest challenges and fears, representing the psychological shadow that must be confronted for personal growth.

- Stories become meaningful when they symbolize larger human experiences and reflect universal themes, as explained through Jungian archetypes and Campbell’s monomyth.

- The hero’s journey involves confronting and integrating one’s shadow aspects, which is key to personal transformation and growth.

- There are different approaches to storytelling: “plotters” who plan meticulously using archetypal structures, and “pantsers” who write more spontaneously. A balance between these approaches can be effective.

- The collective shadow represents the repressed or denied aspects of a group’s psyche, which can manifest in societal issues and conflicts.

- Existential anxiety arises from confronting our cosmic insignificance and the apparent meaninglessness of existence, which can be particularly challenging for trauma survivors.

- Existential therapy aims to help individuals find meaning and purpose despite life’s inherent uncertainties and limitations.

- The villain in a story often represents a point of stunted growth in the hero’s journey, embodying fears and temptations that must be overcome.

- Understanding the psychological underpinnings of character archetypes can help writers create more complex and resonant stories.

- Examples from various works of fiction illustrate how these concepts can be applied in storytelling across different media and genres.

What is a Story?:

If I told you that I moved a bookcase that would not be a story. That is merely information.

What if instead I told you: I went into my attic. I saw an old book case I had been meaning to move, but I did not think I would be able to move it by myself. Feeling brave I decided to try, and after great effort drug it away from the wall. The bookcase had been covering a small window and all of a sudden the attic flooded with light. Wiping my eyes I went and peered through it to see my daughter playing in the backyard from high above her. Suddenly I became overwhelmed with gratitude that this was my own life I saw through the window.

It isn’t emotion that makes a story a story but it certainly helps. A story becomes a story when a series of events become a symbol. Symbolic language that points to a larger meaning makes a story relevant information instead of merely useful information. Mere data is converted into a narrative when it is given the ability to reflect the human experience of the audience. Put simply we make stories by being able to see ourselves or some part of our own experience in an event. This is when history becomes a lesson, my ancestors become my identity, or my beliefs become my purpose.

Our stories are a reflection of us and we are a reflection of our stories. Religion, mythology, storytelling is the attempt to make life symbolic. It is an attempt to make life itself into more than its nuts and bolts and infuse details with humanity. This is part of the reason that Jung saw understanding mythology as key to understanding humanity. Jung saw that myth was not just a list of beliefs that got ancient people through the day, but an attempt to make sense of something that is inside all of us. A son becomes his father by trying to avoid all roads that would lead him there. Parents are threatened by their own insignificance when they see the accomplishments of their children. A couple chooses death over a life without one another. All mythology is aspects of human experience that will continue as long as we continue.

Jungian Archetypes in English Literature and Fiction Writing:

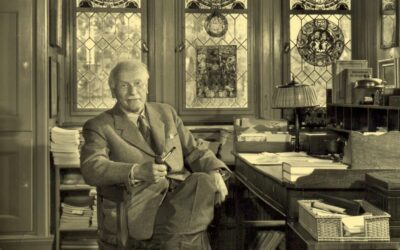

Jungian archetypes are repetitive constructions of human experience. We put them in our stories because they are parts of ourselves. Jung saw dreams as symbols. He saw religions as a symbol and myth as a symbol. Many of Jung’s ideas were expanded on in other fields after his death; however, his ideas have been largely repurposed or disowned by their heritors. Joseph Campbell, a literature professor and comparative religion writer, brought many of Jung’s ideas into the field of anthropology and narrative analysis in the late fifties. Campbell created the concept of the monomyth, the idea that there was a central structure that ran through all myths.

Campbell arrived at this diagram by analyzing common threads that ran throughout all cultures and religions. In this way he continued Jung’s work of finding the central monism beneath human expression. Campbell identified “right hand path” myths that reinforce a local culture’s rules and customs. “Left hand path myths” often opposed or overcame local customs in favor of a heroic journey that Campbell dubbed the monomyth, or the hero’s journey.

Left hand path myths and the journey of the hero were universal across all cultures and similar in many myths and legends in cultures throughout history. Campbell saw the Hero’s journey as a metaphor for the successful life journey of a brave person into the unconscious mind towards eventual self discovery and growth. Campbell saw the events contained in mythological narratives not as external events, but as symbols for an internal process of self acceptance. Through this lens mythology becomes about the defeat and integration of one’s shadow. The quest to discover and integrate the shadow is the engine that drives the monomyth.

The distinction between left-hand and right-hand path myths can be connected to concepts found in Eastern philosophies, such as dharma and moksha. In Hinduism, dharma refers to the moral and ethical principles that govern an individual’s behavior and actions within society. Right-hand path myths, which reinforce cultural norms and customs, can be seen as analogous to the concept of dharma, as they encourage adherence to established social and moral codes.

On the other hand, moksha, in Hinduism and other Indian religions, represents the ultimate goal of spiritual liberation and release from the cycle of birth and death. This concept aligns with the left-hand path myths, which often involve a hero’s journey that transcends or opposes societal norms in pursuit of self-discovery and personal growth. The hero’s journey can be seen as a symbolic representation of an individual’s quest for moksha, as it involves overcoming obstacles, facing one’s inner demons (the shadow), and ultimately achieving a higher state of consciousness or enlightenment.

In Buddhism, the concepts of samsara (the cycle of rebirth) and nirvana (the state of liberation from suffering and attachment) also correspond to the right-hand and left-hand path myths, respectively. Right-hand path myths, which reinforce cultural norms, can be seen as perpetuating the cycle of samsara, while left-hand path myths, which involve a heroic journey of self-discovery, can be interpreted as a path towards nirvana.

“There is the right hand path that keeps you fixed in the proper path of your world. You live a dignified and, in a rich society, a richly developed life. On the other hand, you may flip out. [Students laugh] You have a feeling of incongruity: ‘This doesn’t go with me.’ And you move out. Out into a world of danger. This is known as the left hand path: you follow the way of your own bliss. And you are in a realm in which there are no rules, and since your bliss is not mine, you don’t know where you are going. Here you live a life of danger, creativity, perhaps not a respected life, but certainly an interesting one.” This is “hero’s journey, the night sea journey, the hero’s quest, in which the individual is going to bring forth in his life something that was never beheld before, namely the fulfillment in time and space of his own potentialities.”

-Joseph Campbell

These parallels between Campbell’s left-hand and right-hand path myths and Eastern philosophical concepts demonstrate the universal nature of the human quest for meaning, self-discovery, and liberation. By recognizing the symbolic significance of these mythological structures, we can gain a deeper understanding of our own psychological and spiritual journeys, as well as the collective human experience.

Download our worksheet on archetypes here: Jungian-Types-Worksheet For screenwriting and Fiction-

Understanding Archetypes in Storytelling: Plotters vs. Pantsers

In the world of storytelling, writers often fall into two categories: plotters and pantsers. Plotters are those who meticulously plan their stories, outlining the plot, characters, and themes before writing. They often rely heavily on archetypal structures and patterns to guide their narrative. On the other hand, pantsers, short for “writing by the seat of their pants,” prefer a more spontaneous approach, allowing the story to unfold organically as they write.

Plotters and Archetypes:

Plotters tend to incorporate archetypal elements more deliberately in their writing. They consciously use characters, settings, and plot points that align with universal patterns found in mythology and storytelling. For example, they may deliberately create a hero who embodies the archetypal qualities of bravery, selflessness, and determination, or a mentor figure who guides the hero on their journey. By utilizing these archetypes, plotters can create stories that resonate deeply with readers, as they tap into the collective unconscious and evoke familiar emotional responses.

The advantages of this approach include a clear structure, coherent themes, and a sense of purpose in the narrative. Archetypal stories often feel satisfying and meaningful, as they explore fundamental human experiences and challenges. However, the downside of relying too heavily on archetypes is that the story may feel predictable or formulaic, lacking the element of surprise and originality that can captivate readers.

Pantsers and Spontaneity:

Pantsers, on the other hand, embrace the unknown and allow their stories to develop organically. They may start with a basic premise or a few key characters but allow the plot to emerge through the writing process. This approach can lead to more unexpected twists, unique character developments, and a sense of discovery for both the writer and the reader.

The advantage of the pantser approach is that it can result in fresh, innovative stories that break away from conventional patterns. The characters and their actions may feel more authentic and less constrained by archetypal expectations. This spontaneity can also infuse the writing with a sense of excitement and unpredictability, keeping readers engaged and curious.

However, the downside of pantsing is that the story may lack structure or coherence, especially if the writer struggles to tie together the various plot threads. Without a clear archetypal foundation, the narrative may feel aimless or unsatisfying, failing to deliver the emotional resonance and universal themes that readers crave.

What’s Better, Plotting or Pantsing?:

Ultimately, the most effective approach to storytelling may be a combination of both plotting and pantsing. By understanding and selectively employing archetypes, writers can create stories that tap into the power of universal human experiences while still allowing for spontaneity and originality. Archetypes can serve as a foundation, providing a framework for the story, while the pantser approach allows for unexpected detours and unique flourishes.

When creating characters, drawing inspiration from archetypal psychology and the concept of the hero’s journey can help writers strike a balance between crafting realistic, timeless stories and avoiding the pitfalls of formulaic, predictable plotting. By understanding the archetypal forces that shape human experience, writers can create characters that feel authentic and relatable while still being driven by powerful, universal themes.

As James Hillman, a pioneer of archetypal psychology, often quoted from W.H. Auden, “We are lived by powers we pretend to understand.” This idea suggests that our lives are shaped by deep, unconscious patterns and forces that we may not fully comprehend. By tapping into these archetypal energies when developing characters, writers can create stories that resonate on a profound, psychological level.

By focusing on the archetypal journey rather than adhering to a strict plot structure, writers can create stories that feel organic and character-driven. This approach allows for a more nuanced exploration of the characters’ inner worlds, as they navigate the challenges and transformations that arise from their unique psychological makeup.

When writers understand the archetypal forces at play within their characters, they can develop plots that feel both surprising and inevitable. Rather than relying on tropes or contrived plot points, the story emerges naturally from the characters’ psychological journeys. This approach helps writers avoid the predictability and formulaic nature that can sometimes arise from overly structured plotting.

At the same time, by grounding characters in archetypal themes and motivations, writers can create stories that feel timeless and universal. Even as the specific details of the plot may be unique, the underlying psychological forces that drive the characters will resonate with readers on a deep, unconscious level.

Incorporating insights from archetypal psychology into character development allows writers to strike a balance between planning and spontaneity. By understanding the archetypal forces at work within their characters, writers can create a loose framework that guides the story while still allowing for organic, surprising developments. This approach helps writers avoid the extremes of either rigidly adhering to a predetermined plot or getting lost in a sea of unplanned details.

In summary, by drawing on the insights of archetypal psychology and the hero’s journey, writers can create characters that feel both realistic and timeless. By focusing on the psychological forces that drive character motivation, rather than relying on tropes or formulaic plotting, writers can craft stories that are both surprising and inevitable, resonating with readers on a deep, unconscious level.

Jungian Psychology for Writing Man vs Man and Man vs Self:

The Hero’s Journey and the Shadow

Joseph Campbell’s seminal work, “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” introduced the idea of the hero’s journey—a universal narrative pattern found in myths, legends, and stories across cultures. In this journey, the hero ventures forth from the ordinary world into a realm of supernatural wonder, facing trials, allies, and enemies, before ultimately triumphing and returning home changed.

Central to this journey is the hero’s encounter with their shadow—the dark, repressed aspects of their psyche that they must confront and integrate to achieve wholeness. Psychologist Carl Jung described the shadow as the unconscious part of the personality that the conscious ego rejects or ignores. It is the “villain” within, representing our deepest fears, insecurities, and unacknowledged desires.

The Hero’s Journey (Joseph Campbell):

1. The Ordinary World

– This is the hero’s everyday life before the adventure begins.

2. The Call to Adventure

– The hero is presented with a problem, challenge, or adventure that they must undertake.

3. Refusal of the Call

– The hero initially hesitates or refuses the call to adventure, often due to fear or insecurity.

4. Meeting with the Mentor

– The hero encounters a wise guide or mentor who provides advice, training, or a gift to help them on their journey.

5. Crossing the First Threshold

– The hero fully commits to the adventure and enters the special world, leaving the ordinary world behind.

6. Tests, Allies, and Enemies

– The hero faces various challenges and obstacles, makes friends and allies, and confronts enemies.

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave

– The hero nears the center of the special world and the object of their quest.

8. The Ordeal

– The hero faces their greatest fear or confronts their deepest flaw in a life-or-death crisis.

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword)

– The hero survives the ordeal and obtains the object of their quest or achieves their goal.

10. The Road Back

– The hero begins their journey back to the ordinary world, often pursued by remaining forces of the special world.

11. Resurrection

– The hero faces a final test or challenge, using all they have learned to overcome it and emerge transformed.

12. Return with the Elixir

– The hero returns to the ordinary world with the “elixir,” which can be literal (an object) or metaphorical (knowledge, wisdom, or personal growth) and uses it to benefit their world.

Dan Harmon’s Story Circle:

1. A character is in a zone of comfort

– This is the protagonist’s everyday life, where they feel safe and familiar.

2. But they want something

– The character has a desire or goal that they want to achieve, which will drive their actions.

3. They enter an unfamiliar situation

– The character leaves their comfort zone and ventures into unknown territory in pursuit of their goal.

4. Adapt to it

– The character must learn to navigate the new situation and overcome challenges.

5. Get what they wanted

– The character achieves their goal or gains what they were seeking.

6. Pay a heavy price for it

– The character’s success comes at a cost, often requiring them to sacrifice something important or face consequences.

7. Return to their familiar situation

– The character goes back to their original world, but they are not the same as when they left.

8. Having changed

– The character has grown, learned, or transformed as a result of their journey and the price they paid.

Becoming the Hero

Ultimately, the choice between villain and hero lies within each of us. By embracing the difficult work of self-discovery and shadow integration, we can transform our lives and the lives of those around us. We can break free from the cycle of pain and become the heroes of our own stories, inspiring others to do the same.

In a world that often feels divided and polarized, the call to heroism has never been more urgent. By confronting our own shadows and striving for personal growth, we can collectively create a society of empathy, understanding, and compassion. The journey may be challenging, but the rewards—for ourselves, our loved ones, and the world—are immeasurable.

Jungian Psychology for Writing Man vs Society Stories:

What is the Collective Shadow?

The collective shadow is a concept that extends Jung’s idea of the personal shadow to the level of groups and societies. It represents the dark, disowned, or repressed aspects of a collective psyche, the parts that are deemed unacceptable or inconsistent with the group’s conscious values and self-image. These shadow elements are not inherently negative or evil, but rather represent the parts of the group’s psyche that are denied expression or acknowledgment.

The collective shadow can manifest in various forms, such as scapegoating, projection, denial, or enabling dysfunctional patterns. It is the tendency of groups to project their own unacknowledged flaws, fears, or desires onto others, often in the form of prejudice, discrimination, or hostility towards outgroups. It is the denial of collective responsibility for systemic problems or injustices, the rationalizing of unethical behavior in the name of a higher cause or group loyalty.

At its core, the collective shadow represents the unintegrated aspects of a group’s psyche, the parts that are split off and repressed because they threaten the group’s sense of identity or cohesion. These shadow elements can fester beneath the surface, influencing group dynamics in subtle but powerful ways, until they are brought into conscious awareness and integrated.

The Collective Shadow in Religious Communities:

One of the most striking examples of the collective shadow at play can be found within religious communities. Throughout history, there have been numerous instances of spiritual leaders and organizations engaging in abusive, exploitative, or hypocritical behaviors, despite their professed values of compassion, integrity, and transcendence.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a wave of scandals emerged involving prominent spiritual teachers and communities, particularly within the New Age and Eastern-inspired movements. These leaders, who often preached the importance of ego-transcendence and spiritual enlightenment, were revealed to be engaging in abusive, manipulative, or addictive behaviors behind closed doors.

This dichotomy between the conscious values of the community and the unconscious shadow of its leaders often led to a collective denial or enabling of the problematic behavior. Followers, deeply invested in the idealized image of their teachers and communities, would often turn a blind eye to the red flags or actively defend and rationalize the abusive actions.

This dynamic illustrates the power of the collective shadow to shape group behavior and perception. The unacknowledged desires, fears, and impulses of the community, such as the need for belonging, the fear of uncertainty, or the desire for spiritual validation, can lead to a collective collusion in maintaining a façade of perfection and denying the shadow elements that threaten it.

Integrating the Shadow in Therapy:

While practices such as meditation, mindfulness, and spiritual inquiry can offer valuable tools for self-reflection and personal growth, they alone are often insufficient for fully integrating the shadow aspects of the psyche. These practices can provide glimpses into the depths of one’s being and help cultivate greater self-awareness, but they do not automatically lead to the confrontation and integration of the disowned parts of the self.

Therapists can help clients recognize the patterns and defenses that keep their shadow hidden, and gently challenge them to bring these aspects into conscious awareness. They can assist clients in reframing their self-image, letting go of limiting beliefs and identities, and developing a more integrated and authentic sense of self.

Through the process of shadow work, clients can learn to accept and embrace the full spectrum of their being, including the parts that have been denied or rejected. They can develop greater self-compassion, understanding that their shadow elements are not inherently bad or shameful, but rather represent unmet needs, wounds, or adaptations to past experiences.

As clients integrate their shadow aspects, they can experience a greater sense of wholeness, vitality, and authenticity. They can make more conscious and empowered choices, rather than being driven by unconscious impulses or reactive patterns. They can also develop greater empathy and understanding for others, recognizing that everyone grapples with their own shadow elements.

The Dangers of Ignoring the Collective Shadow:

When groups or communities collectively ignore or deny their shadow aspects, it can lead to a range of destructive dynamics and even atrocities. History is rife with examples of societies engaging in scapegoating, persecution, and violence towards outgroups, often as a way of projecting their own unacknowledged fears, insecurities, or aggression.

The collective shadow can manifest in the form of systemic oppression, discrimination, or marginalization of certain groups based on factors such as race, gender, sexual orientation, or religious affiliation. It can lead to the rationalization of unethical behavior in the name of group loyalty, ideology, or a perceived greater good.

When the collective shadow is not acknowledged and addressed, it can fester and grow, leading to a toxic and dysfunctional group culture. It can perpetuate cycles of abuse, neglect, or exploitation, as the unresolved wounds and traumas of the group are passed down through generations.

As therapists, it is crucial that we are attuned to these dynamics and help clients navigate the complexities of group influence. We must be willing to confront and challenge the collective shadow, both within our clients and within the larger systems and institutions in which we operate.

This requires a deep level of self-awareness and a willingness to examine our own shadow elements as therapists. We must be vigilant about our own biases, blind spots, and countertransference reactions, and actively work to integrate our own disowned aspects.

By modeling this kind of shadow work ourselves, we can create a space of greater authenticity, compassion, and integrity in our therapeutic relationships. We can help our clients develop the tools and resilience needed to navigate the challenges of group dynamics and to find their own path towards wholeness and self-actualization.

Harnessing the Collective Shadow in Fiction Writing:

For authors crafting fictional worlds, understanding the dynamics of the collective shadow can be an invaluable tool for creating rich, nuanced, and psychologically realistic societies and characters. By exploring the shadow elements of fictional groups and cultures, writers can add depth and complexity to their worldbuilding and storytelling.

When creating a fictional society or community, authors can ask themselves what that group is afraid of, what it denies or represses about itself, and what it projects onto others. They can explore how these shadow elements manifest in the group’s beliefs, customs, and social structures, and how they shape the dynamics of power, conflict, and change within that society.

For example, a fictional culture that places a high value on honor and loyalty might have a collective shadow of repressed shame, fear of vulnerability, or unacknowledged aggression. This shadow could manifest in rigid social hierarchies, harsh punishment for perceived disloyalty, or a tendency to scapegoat and attack outsiders.

By weaving these shadow elements into the fabric of their fictional worlds, authors can create settings that feel authentic, complex, and emotionally resonant. They can explore how these dynamics shape the lives and choices of individual characters, and how they contribute to the larger themes and conflicts of the story.

The collective shadow can also inform character development, as individuals within a fictional world are inevitably shaped by the social pressures, norms, and unconscious patterns of their environment. A character who grows up within a society that represses certain emotions or traits might struggle with their own shadow elements, leading to internal conflicts and opportunities for growth and transformation.

By understanding the interplay between individual and collective shadows, authors can create characters who are not just products of their environment, but also agents of change and self-discovery. They can explore how characters navigate the challenges of group dynamics, how they confront and integrate their own shadow aspects, and how they ultimately find their own path towards authenticity and purpose.

Jungian Psychology in Writing Man vs. Nature

In the vast expanse of the universe, human existence appears infinitesimally small, a mere flicker in the grand cosmic dance of space and time. This realization of our cosmic insignificance can evoke a profound sense of existential anxiety, as we grapple with the apparent meaninglessness and indifference of the natural world. For individuals who have experienced trauma, this confrontation with the shadow of nature can be particularly overwhelming, as it may echo the feelings of helplessness, vulnerability, and insignificance that often accompany traumatic experiences. Existential therapy offers a framework for navigating this complex terrain, helping individuals find meaning, purpose, and resilience in the face of our inherent limitations and the challenges posed by trauma.

The Shadow of Nature:

The shadow of nature refers to the vast, impersonal, and often overwhelming realities of the material world that we, as humans, cannot fully comprehend, control, or overcome. It encompasses the unfathomable vastness of the universe, with its countless galaxies, stars, and planets stretching out into infinity. It includes the fundamental forces of physics that govern the behavior of matter and energy, from the subatomic realm to the cosmic scale. The shadow of nature also encompasses the intricate web of biological processes that give rise to life, from the molecular dance of DNA to the complex ecosystems that sustain our planet.

Moreover, the shadow of nature confronts us with the ultimate inevitability of death, the great equalizer that underlies all existence. It reminds us of our mortality, the finite nature of our individual lives, and the impermanence of all things. This awareness can be deeply unsettling, challenging our sense of significance, purpose, and control in the face of an indifferent universe.

For individuals who have experienced trauma, the shadow of nature can take on additional layers of meaning and intensity. Traumatic experiences often involve a profound sense of helplessness, vulnerability, and loss of control, as individuals are confronted with overwhelming events that shatter their assumptions about the world and their place within it. The vastness and indifference of the universe can echo these feelings, reinforcing the sense of insignificance and powerlessness that often accompanies trauma.

Trauma and the Fear of Space:

Trauma patients often struggle with a heightened sensitivity to space and the environment around them. This fear of space can manifest in various ways, such as agoraphobia (fear of open or crowded spaces), claustrophobia (fear of enclosed spaces), or a general sense of unease and hypervigilance in unfamiliar or uncontrolled environments. These spatial anxieties often stem from the traumatic experience itself, where the individual’s sense of safety, control, and boundaries were violated or shattered.

In the aftermath of trauma, the world can feel like a dangerous and unpredictable place, where threats lurk around every corner and safety is never guaranteed. This heightened perception of danger can lead to a constant state of alertness and arousal, as the individual scans their environment for potential threats and attempts to maintain a sense of control over their surroundings.

The fear of space in trauma patients can also be linked to a disturbance in their sense of self and identity. Traumatic experiences can disrupt an individual’s fundamental assumptions about themselves, their relationships, and their place in the world. This can lead to a fragmentation of the self, where the individual feels disconnected from their body, emotions, and sense of agency. In this context, the vastness and impersonality of space can feel threatening, as it mirrors the sense of disconnection and loss of control that often accompanies trauma.

Moreover, the fear of space in trauma patients can be compounded by the existential anxieties evoked by the shadow of nature. The realization of our cosmic insignificance and the indifference of the universe can feel particularly overwhelming for individuals whose sense of safety and meaning has already been shattered by trauma. The vastness of space can serve as a reminder of the individual’s vulnerability and the ultimate lack of control they have over their existence.

Existential Anxiety and the Human Condition:

Existential anxiety is a fundamental aspect of the human condition, arising from the realization that we are alone in an indifferent universe, lacking inherent meaning or purpose. This anxiety is not a pathological state, but rather a natural response to the existential realities of our existence. It is the price we pay for our self-awareness, our ability to reflect on our own mortality and the apparent absurdity of life.

For individuals who have experienced trauma, existential anxiety can be particularly acute, as the traumatic experience itself often shatters the individual’s assumptions about the world and their place within it. Trauma can disrupt the narratives and beliefs that individuals use to make sense of their lives, leaving them feeling lost, disconnected, and without a clear sense of purpose or direction.

In the face of this existential void, individuals may struggle to find meaning and value in their experiences, questioning the significance of their suffering and the purpose of their existence. They may feel a sense of despair or hopelessness, as if their lives have been irreparably damaged by the traumatic event and there is no way forward.

Existential therapy aims to help individuals confront this anxiety head-on, recognizing it as an inherent part of the human condition rather than a pathological state to be eliminated. By acknowledging and accepting the reality of our existential situation, individuals can begin to find authentic ways of living and creating meaning, even in the face of trauma and suffering.

Accepting Our Cosmic Insignificance:

One of the key tasks of existential therapy is to help clients accept their own cosmic insignificance and the ultimate lack of control they have over the universe. This involves a radical shift in perspective, from a narrow focus on the individual self to a broader recognition of our place within the vast web of existence.

Accepting our cosmic insignificance means letting go of the illusion of control, recognizing that we are not the masters of our fate or the captains of our souls. It means acknowledging the limits of human power and knowledge, and the ultimate mystery and uncertainty that underlies all existence.

For trauma patients, this acceptance can be particularly challenging, as the traumatic experience itself often involves a profound loss of control and a shattering of the individual’s sense of agency. Trauma can leave individuals feeling powerless and at the mercy of external forces, struggling to regain a sense of mastery over their lives.

However, by accepting our cosmic insignificance, we can paradoxically find a sense of freedom and liberation. When we let go of the burden of trying to control the uncontrollable, we can focus our energy on what is within our power to change. We can recognize that our value and worth as human beings is not contingent on our ability to master the universe, but rather on our capacity for compassion, connection, and creativity.

Moreover, accepting our cosmic insignificance can help us cultivate a sense of humility and perspective, recognizing that our individual struggles and triumphs are part of a much larger tapestry of existence. By situating our lives within this broader context, we can find a sense of belonging and connection, even in the face of trauma and suffering.

Finding Meaning in the Absurd:

Existential therapy encourages individuals to create their own meaning and purpose in life, despite the apparent absurdity and meaninglessness of existence. This involves a shift from a passive stance of waiting for meaning to be given to us, to an active stance of constructing meaning through our choices and actions.

For trauma patients, finding meaning in the aftermath of a traumatic experience can be a particularly daunting task. Trauma often shatters the individual’s assumptions about the world and their place within it, leaving them feeling lost and disconnected from their previous sources of meaning and value.

However, by actively engaging in the process of meaning-making, individuals can begin to rebuild their sense of purpose and direction in life. This involves identifying and pursuing authentic values, engaging in activities and relationships that are personally meaningful, and taking responsibility for one’s choices and actions.

Existential therapy emphasizes the importance of living authentically, in accordance with one’s deepest values and aspirations. This means being true to oneself, even in the face of external pressures or expectations. It means embracing the freedom and responsibility that comes with being the author of one’s own life story.

For trauma patients, living authentically may involve confronting painful memories and emotions, and integrating the traumatic experience into their larger life narrative. It may involve finding new sources of meaning and purpose, or rediscovering old ones that were lost in the aftermath of the trauma.

By actively constructing a sense of meaning and purpose, individuals can transcend the shadow of nature and the existential anxieties that come with it. They can find a sense of fulfillment and value in their lives, even in the face of the apparent absurdity and indifference of the universe.

Cultivating Resilience and Courage:

Confronting the shadow of nature and the existential anxieties that come with it requires immense resilience and courage. For trauma patients, who have already faced overwhelming challenges and struggles, cultivating these qualities can be particularly important in the healing process.

Existential therapy aims to foster resilience and courage by helping clients develop a strong sense of self, rooted in their deepest values and aspirations. This involves cultivating a sense of inner strength and resources, and learning to trust in one’s own capacity for growth and transformation.

One key aspect of building resilience is developing a sense of coherence and continuity in one’s life story. Trauma can often disrupt the individual’s sense of self and identity, leaving them feeling fragmented and disconnected from their past and future. By helping clients construct a coherent narrative that integrates the traumatic experience into their larger life story, existential therapy can foster a sense of continuity and meaning, even in the face of adversity.

Another important aspect of cultivating resilience is learning to embrace uncertainty and change. The shadow of nature reminds us that the world is ultimately unpredictable and uncontrollable, and that change is an inherent part of existence. By learning to adapt to new circumstances and challenges, and to find meaning and purpose in the face of uncertainty, individuals can develop a greater sense of flexibility and resilience.

Courage, in the existential sense, involves facing one’s fears and anxieties with openness and honesty, rather than avoiding or denying them. For trauma patients, this may involve confronting painful memories and emotions, and learning to tolerate distress and discomfort in the service of growth and healing.

Existential therapy emphasizes the importance of authenticity and self-awareness in the cultivation of courage. By learning to recognize and acknowledge one’s own thoughts, feelings, and desires, individuals can develop a greater sense of self-acceptance and self-compassion. This, in turn, can provide a foundation for facing the challenges and uncertainties of life with greater equanimity and purpose.

Man vs. The Blank Page:

Exploring the application of Jungian psychology, particularly the concept of the shadow, in creating rich and nuanced conflicts in fiction across four key dimensions: man vs. man, man vs. self, man vs. society, and man vs. nature can help writers craft more psychologically complex and resonant stories that illuminate the depths of the human experience.

In man vs. man stories, the shadow often takes the form of projection, where the protagonist’s unacknowledged fears, desires, or weaknesses are embodied by the antagonist. By confronting and ultimately integrating these shadow elements, the protagonist can achieve greater self-awareness and personal growth. This dynamic can be used to create compelling character arcs and interpersonal conflicts.

Man vs. self stories, on the other hand, involve a more direct confrontation with the shadow, as the protagonist grapples with their own inner demons, repressed traumas, or moral dilemmas. Here, the shadow represents the parts of the self that the protagonist has denied or suppressed, and the story arc often involves a journey of self-discovery and integration. Techniques for externalizing these internal conflicts and creating a satisfying character transformation can be explored.

In man vs. society stories, the shadow takes on a collective dimension, representing the unacknowledged or repressed aspects of the social or cultural psyche. The protagonist, often an outsider or rebel, confronts and challenges these shadow elements, which may manifest as systemic injustices, oppressive norms, or societal hypocrisies. This conflict can be used to critique and illuminate the shadow side of social institutions and ideologies.

Finally, in man vs. nature stories, the shadow assumes a more primal and elemental form, representing the vast, impersonal forces of the universe that dwarf human existence. Here, the protagonist must confront their own insignificance and vulnerability in the face of nature’s indifference, and find meaning and purpose in a world that seems absurd or hostile. This conflict can be used to evoke existential themes and showcase the resilience of the human spirit.

Examples from literature, film, and television illustrate how the shadow archetype has been effectively employed in different genres and modes of storytelling. Practical insights and techniques for writers seeking to incorporate Jungian concepts into their own work, such as methods for developing shadow characters, creating symbolic representations of the shadow, and structuring narratives around the process of shadow integration, can be provided.

Ultimately, by understanding and harnessing the power of the shadow, writers can create stories that not only entertain but also illuminate the complexities of the human psyche and the fundamental conflicts that define our existence. By tapping into the rich reservoir of archetypal symbolism and psychological insight offered by Jungian theory, writers can craft stories that resonate on a deep, unconscious level and leave a lasting impact on their readers or audiences.

Writing The Villain:

The terms “protagonist” and “antagonist” have their roots in ancient Greek drama and storytelling. By examining the etymology and meaning of these words through the lens of philology, we can gain a deeper understanding of their significance in narrative structures.

Protagonist:

The word “protagonist” comes from the Greek words “prōtos,” meaning “first,” and “agōnistēs,” meaning “actor” or “competitor.” In ancient Greek drama, the protagonist was the main character or the leading actor in a play. This character was often the central figure around whom the story revolved and whose actions and decisions drove the plot forward.

Over time, the term “protagonist” has come to refer to the main character of a story, typically the one with whom the audience is meant to identify or sympathize. The protagonist is usually the character who undergoes the most significant change or growth throughout the narrative, often as a result of facing challenges and overcoming obstacles.

Antagonist:

The term “antagonist” is derived from the Greek words “anti,” meaning “against,” and “agōnistēs,” meaning “actor” or “competitor.” In ancient Greek drama, the antagonist was the character who opposed the protagonist, often serving as a rival or an obstacle to the main character’s goals.

In modern storytelling, the antagonist is often the character who creates conflict for the protagonist, serving as the primary source of opposition or tension in the narrative. The antagonist’s actions and motivations are typically at odds with those of the protagonist, creating a dynamic that propels the story forward.

It is important to note that while the terms “protagonist” and “antagonist” are often associated with “good” and “evil” respectively, this is not always the case. A protagonist can be flawed or morally ambiguous, while an antagonist may have understandable or even sympathetic motivations. The key defining factor is their role in the narrative structure and their relationship to one another and the change process.

A Representation of Stunted Growth in the Hero’s Journey

In the context of storytelling, the villain is often more than just an antagonist who opposes the hero’s goals. The villain represents a crucial point in the hero’s development, a stage where growth and change have stalled, and the hero must confront and overcome this obstacle to continue their journey. This concept is deeply rooted in the works of Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and Dan Harmon, who have explored the psychological and mythological underpinnings of storytelling.

According to Jung’s theory of the shadow, every individual has a dark aspect of their personality that they often suppress or ignore. The process of integrating the shadow is essential for personal growth and development. In stories, the villain often represents the hero’s unintegrated shadow, the parts of themselves they fear or reject. By confronting and defeating the villain, the hero symbolically integrates their shadow and achieves a higher level of self-awareness and growth.

This concept is further reflected in Campbell’s monomyth and Harmon’s story circle, which outline the archetypal stages of the hero’s journey. At a crucial point in the journey, the hero must face a temptation or challenge that threatens to derail their progress. This is often represented by the villain, who embodies the fears, doubts, and weaknesses that the hero must overcome to continue their growth.

In many stories, the villain’s origin is linked to the hero’s parents or mentors, who may have faced similar temptations and failed to overcome them. This is often revealed through flashbacks or plot twists, showing how the hero’s predecessors were unable to surpass this critical point in their own development. Jung referred to this as “the unlived life of the parent,” suggesting that children often unconsciously seek to fulfill the unrealized dreams and potential of their parents.

The villain’s role as a representation of stunted growth is what makes them truly frightening to the hero. They serve as a cautionary tale, a reminder of what the hero could become if they fail to confront their fears and integrate their shadow. The villain’s power lies not just in their physical or magical abilities, but in their psychological hold over the hero, as they embody the hero’s deepest insecurities and doubts.

By understanding the villain as a symbol of arrested development, writers can create more compelling and psychologically complex characters. The villain’s backstory and motivations should be tied to the hero’s own struggles and fears, creating a sense of connection and conflict that goes beyond simple good vs. evil dynamics. As the hero confronts and defeats the villain, they are not just saving the world or rescuing a loved one, but also overcoming their own inner demons and achieving a new level of personal growth.

The villain in storytelling represents a critical stage in the hero’s development, a point where growth and change have stalled, and the hero must confront their fears and integrate their shadow to continue their journey. By understanding the psychological and mythological underpinnings of this archetype, writers can create more compelling and meaningful stories that resonate with readers on a deep, emotional level.

part 1: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/the-villain-with…nd-screenwriting/

part 2: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/using-jungian-ps…d-fiction-part-2/

part 3: https://gettherapybirmingham.com/applying-jungian…onality-theories/

Did you enjoy the article? Check out the podcast:

Bibliography:

- Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Pantheon Books.

- Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

- Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

- Harmon, D. (2009). Story Structure 101: Super Basic Shit. Channel 101 Wiki.

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Further Reading:

- von Franz, M. L. (1974). Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales. Spring Publications.

- May, R. (1983). The Discovery of Being: Writings in Existential Psychology. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Vogler, C. (2007). The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. Michael Wiese Productions.

- Pearson, C. S. (1991). Awakening the Heroes Within: Twelve Archetypes to Help Us Find Ourselves and Transform Our World. HarperOne.

- Estés, C. P. (1992). Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. Ballantine Books.

- McAdams, D. P. (1993). The Stories We Live By: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self. Guilford Press.

- Hollis, J. (2005). Finding Meaning in the Second Half of Life: How to Finally, Really Grow Up. Gotham Books.

- Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press.

- Booker, C. (2004). The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories. Continuum.

- Johnson, R. A. (1991). Owning Your Own Shadow: Understanding the Dark Side of the Psyche. HarperOne.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

0 Comments