Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4

Read More on Jung here:

Part 1: What was Jung’s Method to Discover Reality?

Jung’s Empirical Phenomenology: Uniting Subjective Spirituality and Objective Science

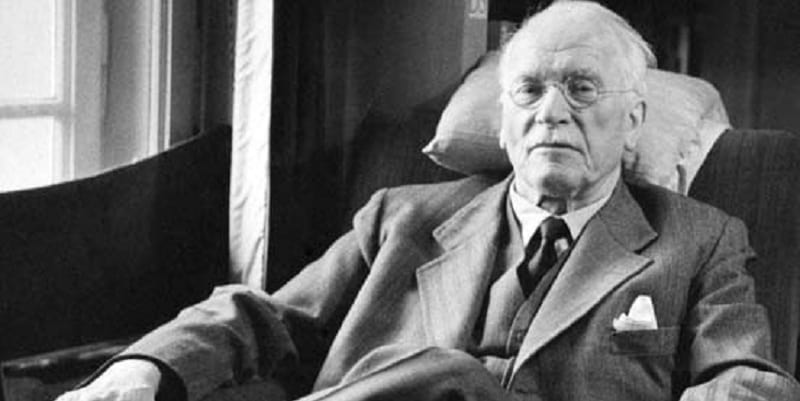

At the heart of Carl Jung’s approach to psychology was a unique synthesis of empiricism and phenomenology, which sought to bridge the seemingly disparate realms of subjective spirituality and objective science. This approach shares similarities with Edmund Husserl’s phenomenological method and William James’ empirical approach to consciousness.

Jung was deeply committed to the scientific method and grounded his theories in meticulous observation and data collection. At the same time, he recognized the profound importance of subjective experience and meaning in shaping the psyche, an idea that resonates with Henri Bergson’s philosophy of intuition and spiritual life.

Jung’s empirical approach is evident in his early work at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital, where he carefully documented and analyzed the symptoms, dreams, and fantasies of his patients. He was not content to simply impose preconceived theories onto the data, but instead allowed the phenomena to speak for themselves. This descriptive, bottom-up method laid the foundation for Jung’s later concepts, such as the archetypes and the collective unconscious, which emerged inductively from years of clinical observation.

However, Jung was not a reductionist who sought to explain away the richness of psychic life in terms of material causes. He recognized that the psyche has its own reality and autonomy that cannot be fully captured by quantitative methods alone. This perspective aligns with Ernst Cassirer’s philosophy of symbolic forms.

This is where Jung’s phenomenological sensibility comes into play. Phenomenology is a philosophical approach that emphasizes the primacy of subjective experience and seeks to understand phenomena as they appear to consciousness, without imposing external frameworks or assumptions. Jung’s approach here was influenced by Martin Heidegger’s work on Being.

For Jung, the psyche was not just an epiphenomenon of brain chemistry or a collection of behavioral responses, but a living, dynamic reality with its own internal logic and structure. He sought to explore this inner world on its own terms, using methods like dream analysis, active imagination, and amplification to uncover the hidden meanings and patterns within the psyche.

Jung’s phenomenological approach allowed him to take seriously the spiritual dimensions of human experience, without reducing them to mere delusions or wishful thinking. He recognized that for many individuals, experiences of the numinous, the transcendent, and the sacred were just as real and impactful as any external event. By honoring the reality of these experiences and seeking to understand their symbolic and archetypal significance, Jung developed a psychology that could encompass both the scientific and the spiritual.

At the same time, Jung was careful not to let his empirical standards slip in the face of spiritual or paranormal phenomena. He insisted on subjecting all claims to rigorous scrutiny and avoided making metaphysical or supernatural assertions. For Jung, the collective unconscious and the archetypes were not literal, ontological entities but empirically derived concepts for mapping the structures of the psyche. This approach shares similarities with William of Ockham’s philosophical nominalism.

This balance of empiricism and phenomenology allowed Jung to develop a truly integrative approach to psychology, one that honored both the objective and subjective dimensions of reality. He recognized that humans are not just passive recipients of external stimuli, but active agents who shape their experience through the creative power of the psyche.

Jung’s holistic vision has important implications for both psychology and spirituality in the modern world. It challenges the reductionist materialism that often dominates contemporary science, while also grounding spirituality in the concrete realities of human experience. By recognizing the empirical reality of psychic phenomena and the symbolic richness of the inner world, Jung points the way towards a more nuanced, multidimensional understanding of the human condition.

For contemporary therapists and researchers, Jung’s approach invites us to cultivate a dual perspective – one that is rigorously empirical and critically discerning, while also remaining open to the depths and mysteries of subjective experience. By honoring both the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of psychic life, we can develop a more comprehensive and humane psychology that truly reflects the fullness of the human spirit.

Ultimately, Jung’s greatest legacy may be his unwavering commitment to the reality of the psyche in all its complexity, beauty, and terror. By daring to venture into the uncharted territories of the soul with the tools of science and the wisdom of the ages, Jung pioneered a new way of understanding ourselves and our world – one that continues to inspire and challenge us to this day.

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- Jung’s approach was initially empirical and descriptive, focused on observing and cataloging psychological phenomena. This methodology was influenced by anthropologists like Jacob Burckhardt and Heinrich Zimmer.

- Jung introduced concepts like archetypes, the collective unconscious, and psychological types as tools for understanding the psyche, not as literal or metaphysical entities. These ideas have been further developed by contemporary analysts like James Hillman and Marie-Louise von Franz.

- The individuation process, a key concept in Jungian psychology, involves integrating various aspects of the personality to achieve wholeness. This concept shares similarities with Martin Buber’s ideas on authentic existence.

- Jung emphasized the importance of the therapeutic relationship and a phenomenological approach to understanding the client’s experience, an idea that resonates with Martin Buber’s I-Thou philosophy of dialogue.

- There’s a tendency to misinterpret Jung’s ideas literally or supernaturally, which goes against his empirical approach.

- Jung’s legacy is contested, with some dismissing his work as unscientific and others using it to support metaphysical beliefs.

- Jungian psychology has implications for contemporary spirituality, ecology, and social transformation, as explored by analysts like Thomas Moore and Marion Woodman.

- The future of Jungian psychology involves adapting to modern challenges while preserving its core insights.

- Post-Jungian thinkers like James Hillman have expanded on Jung’s ideas, emphasizing concepts like “soul-making” over ego development.

- Jungian concepts can be applied to understand and address current societal and environmental issues, as demonstrated by the work of analysts like Jean Shinoda Bolen and Clarissa Pinkola Estés.

Phenomenology and Empiricism

The Pitfalls of Literalism: Why Jung is Often Misunderstood

One of the most persistent challenges facing Jungian psychology is the tendency for people to misinterpret Jung’s ideas in a literal or supernatural sense. Despite his repeated emphasis on the symbolic and metaphorical nature of his concepts, many individuals are drawn to Jungian theory as a kind of esoteric roadmap, promising access to hidden realms of knowledge and power.

This tendency is perhaps most evident in the way some people approach the notion of the collective unconscious and its archetypes. Rather than seeing these as patterns of psychic experience that manifest in diverse cultural forms, they are taken as literal entities or forces that can be directly accessed and manipulated. The result is a kind of pseudo-Jungian mythology, populated by magicians, goddesses, and spirit guides, rather than a mature psychological framework.

There are several reasons why this kind of literalism is so seductive. First and foremost, it appeals to the human desire for certainty and control in an uncertain world. By offering a set of fixed categories and rules for navigating the psyche, literal Jungianism provides a comforting sense of order and meaning, even if it ultimately oversimplifies the complexity of the inner life.

Moreover, the idea that one can tap into hidden reserves of power and knowledge is deeply alluring, especially in a culture that often feels fragmented, shallow, and disenchanted. The promise of direct access to the numinous, whether through dreams, visions, or synchronicities, can be a powerful draw for those seeking a more authentic and meaningful existence.

However, this literal approach to Jungian ideas is ultimately a distortion of Jung’s own views. As we have seen, Jung was deeply skeptical of metaphysical claims and insisted on grounding his psychology in empirical observation and individual experience. He saw his concepts as tools for exploring the psyche, not as dogmatic truths or supernatural entities.

Furthermore, the attempt to use Jungian ideas as a means of escaping or transcending material reality is fundamentally misguided. For Jung, the goal of individuation is not to reject the world in favor of some imaginary realm, but to integrate the conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche, creating a more whole and authentic self. This process necessarily involves engaging with the challenges and limitations of embodied existence, rather than seeking to overcome them through magical thinking.

Indeed, Jung was acutely aware of the dangers of inflation and grandiosity that can arise when individuals identify too closely with archetypal forces or spiritual ideals. He warned against the temptation to see oneself as a guru or savior, emphasizing the need for humility, self-reflection, and grounding in the mundane realities of everyday life.

Ultimately, the literalistic approach to Jungian psychology is a form of spiritual bypassing, using metaphysical ideas to avoid the hard work of genuine self-examination and growth. By projecting one’s own unconscious contents onto external entities or forces, one can maintain a sense of innocence and specialness, while avoiding the painful but necessary process of confronting one’s own shadow.

Jung the Empiricist: Observing the Psyche

First and foremost, it’s essential to understand that Jung was a dedicated empiricist, not a philosopher or mystic as sometimes mischaracterized. He firmly believed in starting with facts and observations, stating, “Facts first and theories later is the keynote of Jung’s work. He is an empiricist first and last.” Rather than proposing a fixed, reductive theory like Freud’s emphasis on sexuality, Jung focused on meticulously observing and describing the vast range of psychological phenomena he encountered in his clinical work.

Jung’s approach was descriptive and comparative, aiming to catalog the patterns and structures of the psyche. He introduced concepts like the archetypes, the collective unconscious, the individuation process, and the psychological types. However, these were not meant as abstract philosophical ideas but as maps to describe the terrain of the mind based on extensive empirical observation.

The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

Two of Jung’s most well-known concepts are the archetypes and the collective unconscious. Archetypes are universal patterns or motifs that emerge spontaneously in the psyche, often embodied in symbolic images like the Wise Old Man, the Great Mother, the Hero, and the Trickster. Jung proposed that these archetypes are innate, inherited predispositions that shape our behavior and experiences. They are not fixed, literal images but fluid, dynamic entities that manifest in endlessly creative ways.

The archetypes arise from what Jung called the collective unconscious – a universal, impersonal layer of the psyche that is shared by all humans. In contrast to Freud’s personal unconscious shaped by individual experiences, the collective unconscious contains the psychological heritage of our species. It is the source of the archetypes as well as instincts, inherited capacities, and evolutionary wisdom that guide our development.

As a therapist, understanding the archetypes and the collective unconscious provides a powerful lens for recognizing the deeper patterns and meanings in your clients’ experiences, dreams, fantasies, and behaviors. By helping clients tap into these universal wellsprings of insight and energy, you can guide them towards greater wholeness and self-realization.

Jung Nominalist

An important point to grasp about Jung’s approach is that he was what he called a “learned nominalist.” This means that while he gave names to the patterns and structures he observed in the psyche, like the shadow, anima/animus, and Self, he acknowledged that these concepts don’t explain the essential nature of these phenomena in any absolute, metaphysical sense. The labels are useful maps for navigating the psyche, but we must be careful not to confuse the map for the territory itself.

Jung was highly skeptical of metaphysical claims and firmly believed that psychology should remain within the bounds of empirical observation. He used his concepts as pragmatic tools for understanding and working with the psyche, but always emphasized the irreducible mystery and complexity of psychological life. As therapists, we must be cautious not to reify Jung’s concepts into fixed, literal entities but to apply them flexibly as orienting frameworks.

The Reality of the Psyche

A central tenet of Jungian psychology is the idea of psychic reality. For Jung, all of our experiences, whether of the external world or the internal world of thoughts, fantasies, and dreams, are mediated through psychic images in the mind. These psychic images have a reality and power of their own, irrespective of their correspondence to external facts.

This insight has important implications for therapy. It suggests that the way a client imagines and interprets their experience is psychologically real and meaningful, even if not objectively “true.” By focusing on the psychological plane, we can work with the living reality of the client’s psyche and help them find creative ways to transform their relationship to their inner world.

The Individuation Process

A key goal of Jungian therapy is to support the individuation process – the lifelong journey towards wholeness and self-realization. Individuation involves differentiating oneself from collective norms, acknowledging and integrating the various conscious and unconscious aspects of one’s personality, and discovering one’s unique purpose and path in life.

As therapists, we can facilitate individuation by helping clients explore the neglected or repressed parts of their psyche, like the shadow (the unconscious, inferior, or rejected aspects of the personality), the anima/animus (the unconscious feminine/masculine qualities), and the Self (the central, integrating archetype of wholeness). By courageously facing these inner figures and learning to dialogue with them, clients can achieve a more balanced, harmonious, and authentic sense of self.

Psychological Types

Another valuable Jungian framework for therapists is the theory of psychological types. Based on empirical observation, Jung proposed that people tend to have innate preferences for certain attitudes (introversion or extraversion) and functions (thinking, feeling, sensation, intuition). By understanding a client’s psychological type, we can tailor our therapeutic approach to their natural style of processing information and making decisions.

However, Jung also emphasized that type preferences are not fixed, static categories but dynamic potentials that can and should be developed over time. The goal is not to box clients into limiting labels but to help them harness their strengths while also cultivating their less developed functions. Ultimately, individuation involves transcending and integrating the opposites within the personality.

The Importance of the Therapeutic Relationship

Jung placed great emphasis on the therapeutic relationship as a key catalyst for psychological healing and growth. He saw therapy not as a sterile, one-way treatment but as a dialectical, collaborative process in which both therapist and client are transformed. The therapist must be willing to be psychologically impacted by the client and to form a genuine, empathetic connection.

At the same time, Jung believed the therapist must maintain appropriate boundaries and not impose their own unconscious material onto the client. The therapist’s role is to be a supportive witness and guide as the client’s psyche unfolds according to its own inner logic and timetable. By providing a safe, nonjudgmental space for exploration, therapists can help clients reconnect with their own inner wisdom and capacity for growth.

Jung’s Phenomenological Method

To truly grasp Jung’s approach, it’s crucial to understand his phenomenological method. Phenomenology is a philosophical movement that emphasizes the direct investigation of subjective experience, suspending preconceived theories and judgments. Jung applied this method to the study of the psyche, focusing on the way psychological phenomena appear to consciousness.

For Jung, the psyche is not a static, objective entity but a dynamic, unfolding process that can only be understood through careful observation and description of its manifestations. He sought to explore the structures and patterns of the psyche as they emerge in dreams, fantasies, symbols, and symptoms, without reducing them to predetermined categories or explanations.

This phenomenological approach allows therapists to stay close to the client’s lived experience and to appreciate the unique, idiosyncratic ways in which their psyche expresses itself. By bracketing theoretical assumptions and attending to the phenomena themselves, we can develop a more nuanced, contextual understanding of each individual’s psychological world.

The Battle Over Jung’s Legacy

Despite Jung’s clear emphasis on empiricism and his rejection of metaphysical claims, his legacy remains contested by various factions seeking to claim him for their own agendas. On one side are those who see Jung as a charlatan or mystic, dismissing his work as unscientific and speculative. On the other are those who embrace Jung as a way to bypass scientific rigor and retreat into spiritualism or esotericism.

The truth is that Jung’s epistemological lens is often sanitized or misrepresented by both his critics and his admirers. Modern psychology, especially in America, has tended to strip Jung’s ideas of their nuance and depth, reducing them to simplistic formulas or self-help platitudes. Meanwhile, some in the New Age or alternative spirituality movements have appropriated Jung’s concepts as a way to lend credibility to their own metaphysical beliefs, ignoring his insistence on empirical observation.

The result is that Jung’s true legacy is often preserved by a relatively small group of scholars and practitioners who have taken the time to grapple with the complexity and subtlety of his thought. These individuals recognize that Jung was neither a mystic nor a materialist, but a pioneering researcher who sought to map the contours of the psyche using rigorous empirical methods.

As therapists, it’s essential that we approach Jung’s ideas with a critical, discerning eye, neither accepting them blindly nor dismissing them out of hand. We must be willing to engage with the full depth and range of Jung’s work, while also subjecting his concepts to ongoing testing and refinement in the crucible of clinical practice.

Jungian Psychology and Contemporary Spirituality

In “Jung and the New Age”, David Tacey points out that Hillman, the founder of archetypal psychology and a prominent post-Jungian thinker, emphasized the importance of “soul-making” over ego development. For James Hillman, the goal of individuation was not to strengthen the ego, but to cultivate a deeper relationship with the archetypal dimensions of the psyche. This involved a kind of “letting go” of the narrow, controlling ego and opening up to the mythic and imaginal realms. Tacey suggests that Hillman’s perspective offers a valuable counterpoint to more ego-centric forms of spirituality and self-help.

Tacey also draws upon Immanuel Kant’s idea of the sublime, which involves an experience of awe and terror in the face of something vast and overpowering, such as the immensity of nature. For Kant, the sublime served to shatter the ego’s sense of centrality and control, revealing the limits of human reason and power. Tacey argues that this kind of ego-disrupting encounter with the numinous is an essential part of the spiritual journey, one that is often neglected in New Age emphasis on positive thinking and self-affirmation.

Finally, Tacey discusses H. D. Thoreau’s experiments in simple living and immersion in nature, as described in works like “Walden”. For Thoreau, the goal was to strip away the artificial layers of social conditioning and material distraction in order to discover a more authentic and essential self. This involved a kind of “losing” of the socially constructed ego in order to find a deeper connection with the natural world and one’s own inner depths. Tacey suggests that Thoreau’s example points to the importance of solitude, simplicity, and nature as key elements in the process of spiritual transformation.

Throughout these discussions, Tacey emphasizes the value of “losing the self” in the sense of letting go of the narrow, ego-driven self in order to connect with something larger and more profound. He argues that this is a crucial aspect of the spiritual journey that is often overlooked or misunderstood in contemporary New Age thought, which tends to focus on self-improvement and personal empowerment. By engaging with the ideas of thinkers like Hillman, Kant, and Thoreau, Tacey suggests that we can deepen our understanding of what it means to truly “find ourselves” by first losing our attachment to the limited ego.

As we move into the 21st century, Jungian ideas are increasingly relevant for understanding and addressing the spiritual needs of our time. Jung himself prophesied the emergence of a “third era” in which the split between science and religion, reason and mysticism, would be healed in a new way. This “post-secular” spirituality would draw upon the insights of depth psychology to foster a mature, grounded approach to the sacred.

One area where Jungian thought has significant implications is ecology. Jung’s emphasis on the interconnectedness of all life and the importance of reconnecting with the natural world resonates strongly with the environmental challenges we face today. By cultivating a sense of the sacredness of nature, as well as integrating our own wild, instinctual sides, we can develop a more sustainable and holistic way of being on the planet.

Jungian psychology also has much to offer in terms of social and political transformation. Concepts like the shadow and the collective unconscious shed light on the deep-rooted patterns of oppression, violence, and intolerance that plague our world. A Jungian approach calls for a fearless reckoning with the darker aspects of our psyche and society, rather than projecting them onto others or trying to suppress them. By bringing the unconscious into conscious awareness, we can work towards greater wholeness and justice.

In terms of personal spirituality, Jungian ideas provide a rich framework for inner growth and discovery. The New Age movement, while sometimes prone to superficiality and narcissism, reflects a genuine yearning for direct experience of the numinous that traditional religious institutions often fail to satisfy. By drawing upon Jungian practices like dream work, active imagination, and shadow integration, individuals can cultivate a more authentic and transformative spiritual path.

As therapists, we have a crucial role to play in facilitating this post-secular spiritual awakening. By helping clients to explore their own depths and connect with the archetypal dimensions of their psyche, we can support them in developing a more mature and integrated approach to the sacred. At the same time, we must remain critical and discerning, avoiding the pitfalls of literalism and subjectivism that can sometimes beset Jungian circles.

The Future of Jungian Psychology

Looking forward, the future of Jungian psychology itself is both promising and challenging. On the one hand, Jung’s core insights – the reality of the psyche, the importance of symbol and myth, the centrality of the individuation process – remain as vital and relevant as ever. As our world becomes increasingly complex and fragmented, the need for a psychology of wholeness and meaning is more urgent than ever.

On the other hand, Jungian thought must continue to evolve and adapt to the needs and challenges of our time. This means grappling honestly with the limitations and blind spots in Jung’s work, such as his lack of engagement with issues of gender, race, and power. It means being open to new developments in fields like neuroscience, trauma studies, and social justice, while still preserving the essential wisdom of the Jungian tradition.

Ultimately, the future of Jungian psychology will depend on the creativity and commitment of those who practice it. As therapists, scholars, and seekers, we are called to engage with Jung’s ideas in a spirit of critical reflection and imaginative renewal. By staying true to the empirical, phenomenological, and transformative heart of Jung’s work, while also being willing to question and expand upon it, we can help to build a psychology for the 21st century and beyond.

You Just Read Part 1

Bibliography:

Jung, C.G. (No date provided). Various works referenced but not specifically cited.

Tacey, D. (No date provided). “Jung and the New Age”.

Hillman, J. (No date provided). Works on archetypal psychology referenced but not specifically cited.

Kant, I. (No date provided). Works on the concept of the sublime referenced but not specifically cited.

Thoreau, H.D. (No date provided). “Walden” and other works on simple living referenced.

0 Comments