Who was Henri Bergson?

“The pure present is an ungraspable advance of the past devouring the future. In truth, all sensation is already memory.”

― Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory

Henri Bergson (1859-1941) was a seminal French philosopher who revolutionized our understanding of time, consciousness, and evolution. His innovative ideas challenged the dominant mechanistic paradigm of his era and paved the way for the emergence of process philosophy, phenomenology, and vitalism. Bergson’s thought continues to inspire and provoke across a wide range of fields, from metaphysics and psychology to art and spirituality.

Life and Career

Bergson was born into a prominent Jewish family in Paris in 1859. After studying at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure, he obtained his doctorate in philosophy in 1889 with the thesis Time and Free Will. This groundbreaking work laid the foundations for his lifelong explorations of temporality, subjectivity, and creativity.

Bergson went on to teach at various institutions, including the Collège de France, where he held a chair from 1900 to 1914. His lectures attracted huge audiences and made him a philosophical celebrity, with admirers ranging from William James and Alfred North Whitehead to Nikos Kazantzakis and Gertrude Stein. In 1914, Bergson was elected to the Académie Française, solidifying his stature as one of the preeminent thinkers of his generation.

Bergson’s intellectual triumphs were matched by personal hardships, including chronic pain and insomnia. Despite these challenges, he maintained a rigorous work ethic and a deep commitment to public engagement. During World War I, he undertook diplomatic missions to the United States, helping to secure American support for the Allied cause. In 1927, Bergson was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, in recognition of his profound and vitalizing ideas.

The rise of Nazism and antisemitism in the 1930s cast a dark shadow over Bergson’s final years. While he had converted to Catholicism in his youth, he insisted on being identified as a Jew after the Vichy regime’s anti-Jewish laws were enacted. Weakened by illness and dispirited by the global crisis, Bergson died in occupied Paris in January 1941.

Key Ideas and Theories

Duration and the Critique of Spatialized Time

Bergson’s most celebrated and enduring contribution to philosophy is his reconceptualization of time as duration (durée). In works such as Time and Free Will (1889) and Creative Evolution (1907), he argued that the scientific, spatialized conception of time as a homogeneous medium misrepresents the true nature of temporal experience.

For Bergson, lived time is not a sequence of discrete, quantifiable instants, but a dynamic, heterogeneous flow in which past, present, and future interpenetrate. Duration is the continuous, qualitative unfolding of consciousness, irreducible to the static snapshots of clock time. By privileging space over time, Bergson argued, science and common sense obscure the reality of change, novelty, and creativity.

Bergson’s critique of spatialized time had far-reaching implications. It challenged the deterministic worldview of classical physics, opening up new ways of thinking about causality, evolution, and the nature of the universe. It also resonated with modernist artists and writers, who sought to capture the flux and fluidity of subjective experience in their work.

Intuition and the Limits of Intellect

Closely related to Bergson’s concept of duration is his distinction between intuition and intellect. For Bergson, the intellect is a pragmatic faculty evolved to manipulate matter and navigate the challenges of survival. While powerful in its domain, the intellect is ill-suited to grasping the dynamic, interpenetrating flow of consciousness.

Intuition, by contrast, is a direct, sympathetic coincidence with the inner nature of things. By plunging into the stream of duration, intuition apprehends the continuity and indivisibility of lived experience. Where the intellect spatializes and quantifies, intuition grasps the qualitative and the ineffable.

In works such as An Introduction to Metaphysics (1903), Bergson argued that intuition is the key to philosophical knowledge. By transcending the limits of the intellect and embracing the fluidity of duration, we can gain insight into the nature of consciousness, freedom, and the élan vital that animates the universe.

Bergson’s valorization of intuition had a profound impact on 20th-century thought. It inspired phenomenologists such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Emmanuel Levinas to explore the pre-reflective dimensions of experience. It also resonated with artists and mystics who sought to access deeper levels of reality through non-rational means.

Creative Evolution and the Élan Vital

Bergson’s magnum opus, Creative Evolution (1907), offered a radical reinterpretation of the history of life. Rejecting both mechanism and finalism, Bergson proposed that evolution is a creative, open-ended process driven by an internal impulse he called the élan vital.

The élan vital is not a transcendent force or intelligent designer, but an immanent, indivisible current of life that flows through all living beings. It is the source of the novelty, unpredictability, and inventiveness that characterize the unfolding of life on Earth.

For Bergson, evolution is not a gradual, continuous process of adaptation, but a series of leaps and bounds marked by the emergence of new forms and capacities. Consciousness itself is the crowning achievement of the élan vital, a creative response to the challenges of matter that opens up new horizons of freedom and possibility.

Bergson’s vitalist conception of evolution had a significant impact on philosophy, biology, and the arts. It challenged the reductionism and determinism of neo-Darwinian theories, emphasizing the role of contingency, creativity, and inner directedness in the history of life. It also inspired a generation of modernist artists and writers, from Henri Matisse to D.H. Lawrence, who saw in the élan vital a source of spiritual and aesthetic renewal.

Applications to Trauma and Psychotherapy

While Bergson did not directly address the issues of trauma and psychotherapy, his ideas have important implications for our understanding of psychological suffering and healing. By emphasizing the fluid, dynamic nature of consciousness and the primacy of intuition over intellect, Bergson offers a framework for conceptualizing and treating trauma that goes beyond traditional, medicalized approaches.

Trauma as a Disruption of Duration

From a Bergsonian perspective, trauma can be understood as a disruption of the continuous flow of duration. Traumatic events shatter the coherence and continuity of lived experience, fragments consciousness into disconnected moments. The past becomes an unbearable weight, intruding on the present in the form of flashbacks, nightmares, and dissociative states.

In this light, the goal of trauma therapy is not simply to process and integrate traumatic memories, but to restore the fluid, dynamic flow of duration. This involves helping the traumatized individual reconnect with the vital, creative impulse of life – the élan vital – that has been blocked or distorted by the traumatic rupture.

Intuition and the Limits of Talk Therapy

Bergson’s emphasis on intuition as a mode of knowing suggests that purely intellectual or language-based approaches to trauma may be limited. While talk therapy can be valuable in providing a safe space for self-expression and reflection, it may not be sufficient to access the deeper, pre-reflective layers of traumatic experience.

Somatic and experiential therapies, such as Somatic Experiencing, EMDR, or art therapy, may be more effective in tapping into the intuitive, embodied dimensions of trauma. By working with sensation, movement, and imagery, these approaches can help to release the frozen energy of the traumatic response and restore the natural flow of duration.

The Élan Vital and Post-Traumatic Growth

Bergson’s concept of the élan vital offers a hopeful vision of the human capacity for resilience and transformation in the face of trauma. Just as the élan vital propels the creative evolution of life, it can also fuel the process of post-traumatic growth and renewal.

By connecting with the vital, creative impulse within themselves, trauma survivors can transcend the limitations imposed by their wounds and actualize new possibilities for healing and flourishing. This may involve developing new capacities for empathy, compassion, and meaning-making, or discovering untapped sources of strength and creativity.

From a Bergsonian standpoint, post-traumatic growth is not a return to a pre-traumatic state of functioning, but a qualitative leap forward into a new mode of being. It is a manifestation of the open-ended, unpredictable nature of the élan vital, which can transform even the most devastating experiences into opportunities for growth and renewal.

Henri Bergson’s philosophy of time, intuition, and creative evolution offers a rich and provocative framework for understanding the nature of consciousness, suffering, and healing. By challenging the mechanistic, deterministic worldview of his era, Bergson opened up new ways of thinking about the fluidity, creativity, and resilience of the human spirit.

For those working with trauma, Bergson’s ideas invite us to look beyond the surface of symptoms and behaviors to the deeper, pre-reflective dimensions of experience. They remind us of the importance of intuition, embodiment, and creativity in the healing process, and of the transformative potential of the élan vital that animates all life.

As we grapple with the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, Bergson’s thought remains a vital resource for anyone seeking to understand and alleviate the suffering of the human condition. By embracing the dynamic, open-ended nature of consciousness and tapping into the wellsprings of creativity and resilience within ourselves, we can navigate even the darkest passages of life with grace, courage, and hope.

Comparison with Jungian Intuition of the MBTI and Beebe Model

Bergson’s concept of intuition bears interesting similarities and differences to the notion of intuition in Carl Jung’s psychological type theory, which forms the basis of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and John Beebe’s model of psychological types. While Bergson and Jung were contemporaries and shared certain philosophical influences, they developed their ideas in different contexts and for different purposes.

Intuition in Jungian Type Theory

In Jung’s theory of psychological types, intuition is one of the four basic functions of consciousness, along with sensation, thinking, and feeling. Jung defined intuition as a kind of perception that goes beyond the immediate sensory data to apprehend the deeper patterns, possibilities, and meanings inherent in a situation.

For Jung, intuition is a non-rational, unconscious process that is more concerned with the future than the present. It is the function that allows us to grasp the big picture, to see the forest rather than the trees, and to anticipate new trends and opportunities. Intuitive types are often imaginative, innovative, and oriented towards novelty and change.

In the MBTI, which operationalizes Jung’s theory, intuition is contrasted with sensing as a way of gathering information. Intuitive types (N) are more interested in the abstract, theoretical, and imagined, while sensing types (S) are more grounded in the concrete, practical, and tangible details of experience.

Beebe’s model expands on Jung’s theory by proposing eight function-attitude archetypes that structure the psyche. In this model, intuition can take on different roles and expressions depending on its place in the individual’s type structure. For example, the “Eternal Child” archetype is associated with playful, spontaneous, and imaginative forms of intuition, while the “Trickster” archetype is linked to disruptive, subversive, and iconoclastic intuitions.

Comparison with Bergsonian Intuition

While there are some superficial similarities between Jungian and Bergsonian intuition, there are also significant differences in their philosophical underpinnings and implications.

Like Jung, Bergson sees intuition as a non-rational, non-discursive mode of apprehension that goes beyond the immediate data of perception. Both thinkers emphasize the role of intuition in grasping the deeper patterns and possibilities inherent in reality, and in transcending the limitations of sensory experience and logical analysis.

However, Bergson’s concept of intuition is rooted in his ontology of duration and creative evolution, while Jung’s theory is primarily psychological and typological in nature. For Bergson, intuition is not just a way of perceiving or gathering information, but a direct coincidence with the flow of reality itself. It is the means by which we can apprehend the continuous, indivisible, and heterogeneous nature of duration, as opposed to the spatialized, homogeneous time of the intellect.

Moreover, Bergsonian intuition is not opposed to sensation in the same way that Jungian intuition is. For Bergson, both intuition and intellect are rooted in perception, but they represent different ways of extending and interpreting the immediate data of consciousness. Intuition apprehends the dynamic, interpenetrating flux of duration, while the intellect breaks it down into distinct, immobile elements.

Another key difference is that Bergsonian intuition is more closely tied to the concept of the élan vital and the creative impulse of life. For Bergson, intuition is not just a cognitive function, but a vital, embodied participation in the unfolding of reality. It is the means by which we can tap into the creative energy that animates the universe and direct it towards new forms of expression and actualization.

Finally, while both Bergson and Jung see intuition as a source of innovation and change, they have different views on its relationship to the unconscious. For Jung, intuition is primarily an unconscious process that operates independently of the ego and can be integrated through individuation. For Bergson, intuition is a supra-conscious faculty that transcends the opposition between the conscious and the unconscious, the individual and the universal.

Implications for Trauma and Psychotherapy

Despite these differences, both Jungian and Bergsonian concepts of intuition have important implications for the understanding and treatment of trauma.

From a Jungian perspective, cultivating intuition can be a valuable resource for trauma survivors, helping them to see beyond their immediate suffering and to envision new possibilities for healing and growth. Intuitive insights can provide a sense of meaning and purpose in the face of adversity, and can guide individuals towards the people, places, and experiences that will support their recovery.

However, the Jungian model also suggests that trauma can distort or repress intuitive functioning, leading to a one-sided reliance on sensation and thinking. Restoring balance and integration among the four functions may be an important goal of trauma therapy from this perspective.

The Bergsonian view, on the other hand, suggests that trauma disrupts the fluid, dynamic flow of duration and vitality that is the essence of intuition. Reconnecting with the élan vital through embodied, creative, and intuitive practices may be crucial for overcoming the stasis and fragmentation of traumatic experience.

Moreover, the Bergsonian emphasis on the non-discursive, non-representational nature of intuition may have important implications for the role of language and narrative in trauma therapy. While telling one’s story can be a valuable part of the healing process, it may not be sufficient to fully access and transform the deeper layers of traumatic memory that are encoded in sensation, emotion, and bodily experience.

Somatic and arts-based therapies that engage intuition directly, without relying exclusively on verbal processing, may be particularly effective from this perspective. By tapping into the creative, vital energy of the élan vital, these approaches can help trauma survivors to reconnect with their own inner resources and to actualize new possibilities for growth and flourishing.

Integrating Bergson’s Insights into Psychotherapy:

Cultivating Intuition:

Encourage clients to develop their intuitive capacities through practices such as mindfulness, somatic awareness, and creative expression. Help them learn to trust their inner wisdom and navigate the complexities of their experience with greater ease and fluidity.

Embracing Duration:

Support clients in reconnecting with the fluid, dynamic nature of their lived experience, beyond the limitations of static, conceptual categories. Use experiential and narrative approaches to help them integrate past, present, and future into a cohesive, meaningful whole.

Accessing the Élan Vital:

Help clients tap into the creative, generative impulse within their psyche through practices such as art therapy, dream work, and embodied exploration. Nurture their capacity for resilience, growth, and transformation in the face of life’s challenges.

Co-Creating Meaning:

Engage with clients as active, collaborative partners in the therapeutic process, rather than as passive recipients of expertise or intervention. Foster a space of openness, curiosity, and emergent possibility in which new insights, experiences, and directions can unfold.

Contextualizing Suffering:

Recognize the ways in which individual suffering is intimately bound up with larger social, cultural, and historical contexts. Work with clients to identify and challenge the dehumanizing and objectifying forces that contribute to their distress, and support them in reclaiming their inherent dignity and worth.

Fostering Interconnectedness:

Help clients recognize their fundamental interconnectedness with all of life, and the ways in which their personal journey of healing and growth is woven into the larger tapestry of our shared existence. Encourage them to cultivate compassion, empathy, and a sense of purpose in contributing to the greater good.

By integrating these principles and practices into their work, therapists can offer their clients a more holistic, dynamic, and transformative approach to healing and growth, one that honors the creative, generative potential of the human spirit and the living, ever-evolving nature of reality. In doing so, they can contribute to the ongoing evolution of consciousness and the flourishing of life in all its diverse expressions.

Bergson’s Legacy and Relevance for the 21st Century:

Henri Bergson’s philosophy, though developed in the early 20th century, remains deeply relevant and compelling for our contemporary world. His ideas offer a powerful counterpoint to the dominant paradigms of materialist reductionism, mechanistic determinism, and the objectification of human experience that continue to shape much of modern thought and culture.

In an age of accelerating technological change, environmental crisis, and social upheaval, Bergson’s emphasis on the primacy of lived experience, the creative power of consciousness, and the interconnectedness of all life provides a much-needed corrective to the fragmenting and dehumanizing tendencies of our times. His vision of a world animated by the élan vital, the ever-evolving impulse towards novelty, growth, and transformation, offers a source of hope and inspiration in the face of the existential challenges we confront as a species.

For psychotherapy and the mental health field, Bergson’s ideas point towards a more holistic, integrative, and transformative approach to healing and growth. By recognizing the fluid, dynamic nature of consciousness, the generative potential of the psyche, and the inseparability of individual and collective well-being, therapists can offer their clients a more empowering and meaningful path to wholeness and flourishing.

At the same time, Bergson’s philosophy challenges us to rethink the very nature and purpose of therapeutic work in the 21st century. Rather than a narrowly focused, problem-solving endeavor, therapy becomes a space of creative inquiry and exploration, a collaborative process of unfolding new possibilities for individual and collective transformation. It becomes a way of participating in the larger story of the universe, of aligning ourselves with the evolutionary impulse towards greater complexity, consciousness, and compassion.

As we navigate the uncharted territories of our rapidly shifting world, Bergson’s wisdom offers a compass and a guide, reminding us of the enduring power and potential of the human spirit to adapt, innovate, and thrive in the face of uncertainty and change. By embracing his vision of a dynamic, interconnected, and ever-evolving reality, we can cultivate the resilience, creativity, and sense of purpose needed to meet the challenges of our times with grace, courage, and wisdom.

In the end, Bergson’s legacy is an invitation to reconnect with the living, pulsing heart of existence, to plunge into the stream of duration and discover the inexhaustible richness and beauty of life in all its forms. It is a call to awaken to our true nature as creative, conscious, and interconnected beings, and to take up the sacred work of healing and transforming ourselves and our world. As we step into the unknown future that lies ahead, may we do so with open hearts and minds, guided by the eternal wisdom of the élan vital and the unending dance of becoming.

Key Published Works by Henri Bergson

Time and Free Will (1889) –

Bergson’s doctoral thesis, in which he first develops his concept of duration and critiques the spatialization of time in science and philosophy.

Matter and Memory (1896) –

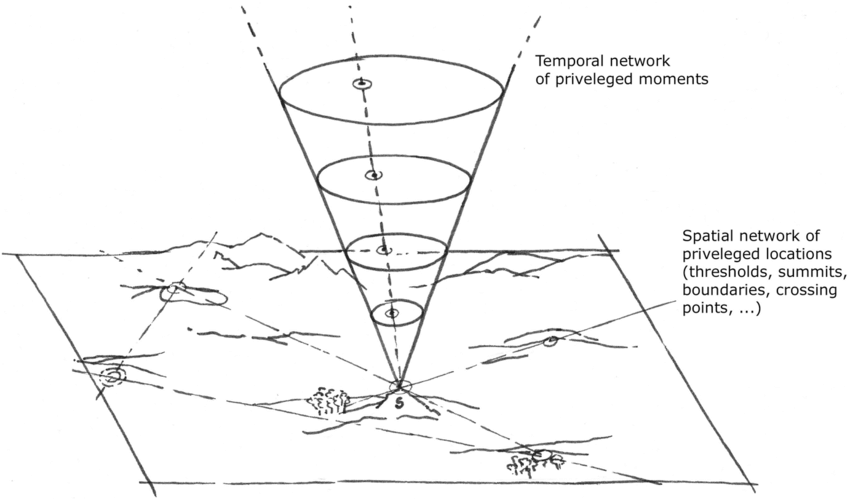

An exploration of the relationship between mind and body, perception and memory, that introduces Bergson’s famous image of the memory cone.

Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (1900) – A short but influential work that analyzes the social and psychological functions of laughter and humor.

An Introduction to Metaphysics (1903) –

A concise and accessible exposition of Bergson’s method of intuition and its application to philosophical problems.

Creative Evolution (1907) –

Bergson’s magnum opus, which offers a sweeping reinterpretation of the history of life in terms of the élan vital and creative evolution.

Mind-Energy (1919) –

A collection of essays that apply Bergson’s ideas to a range of topics, from psychology and education to religion and ethics.

The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (1932) – Bergson’s final major work, which distinguishes between the closed and open forms of morality and religion and proposes a mystical, dynamic conception of the divine.

The Creative Mind (1934) –

An anthology of essays and lectures that showcase the development and application of Bergson’s thought across his career.

Henri Bergson’s Life Timeline

1859 – Born on October 18th in Paris, France, to a Jewish family of Polish and English descent.

1868 – Enters the Lycée Fontanes (now known as Lycée Condorcet) in Paris, where he excels in his studies.

1878 – Graduates from the Lycée Fontanes with honors and a prize in mathematics.

1878 – Enters the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris to study philosophy.

1881 – Graduates from the École Normale Supérieure.

1883 – Begins teaching philosophy at the Lycée Blaise-Pascal in Clermont-Ferrand.

1889 – Completes his doctoral thesis, “Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness.”

1891 – Marries Louise Neuberger, a cousin of Marcel Proust.

1896 – Publishes “Matter and Memory,” a work that explores the relationship between mind and body.

1900 – Appointed as a professor at the Collège de France in Paris.

1900 – Publishes “Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic.”

1903 – Publishes “An Introduction to Metaphysics,” outlining his philosophical method of intuition.

1907 – Publishes “Creative Evolution,” his most famous work, which introduces the concept of the élan vital and the theory of creative evolution.

1914 – Elected to the Académie Française, becoming one of the forty “immortals.”

1914-1918 – Serves as a diplomat during World War I, visiting the United States to promote the French cause.

1919 – Publishes “Mind-Energy,” a collection of essays on various topics.

1922 – Retires from his position at the Collège de France.

1927 – Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “in recognition of his rich and vitalizing ideas and the brilliant skill with which they have been presented.”

1932 – Publishes “The Two Sources of Morality and Religion,” exploring the social and mystical dimensions of human experience.

1933 – Renounces all public activities as a protest against anti-Semitic regulations imposed by Nazi Germany.

1934 – Publishes “The Creative Mind: An Introduction to Metaphysics,” a collection of essays and lectures.

1939 – Death of his wife, Louise.

1939-1940 – The onset of World War II and the occupation of France by Nazi Germany.

1941 – Passes away on January 3rd at the age of 81 in occupied Paris.

1941 – Friends and admirers arrange for Bergson’s philosophical works to be smuggled out of Nazi-occupied France to be published in the United States.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Philosophy

Citations

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Drury, M. O’C. (1973). The Danger of Words and Writings on Wittgenstein. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Grayling, A. C. (1996). Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bibliography

- Drury, M. O’C. (1973). The Danger of Words and Writings on Wittgenstein. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Grayling, A. C. (1996). Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hacker, P. M. S. (1986). Insight and Illusion: Themes in the Philosophy of Wittgenstein. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Heaton, J. M. (2010). The Talking Cure: Wittgenstein’s Therapeutic Method for Psychotherapy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Monk, R. (1990). Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Sluga, H. D. (2011). Wittgenstein. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1961). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here.

0 Comments