Who is Peter Sloterdijk?

Who is Peter Sloterdijk?

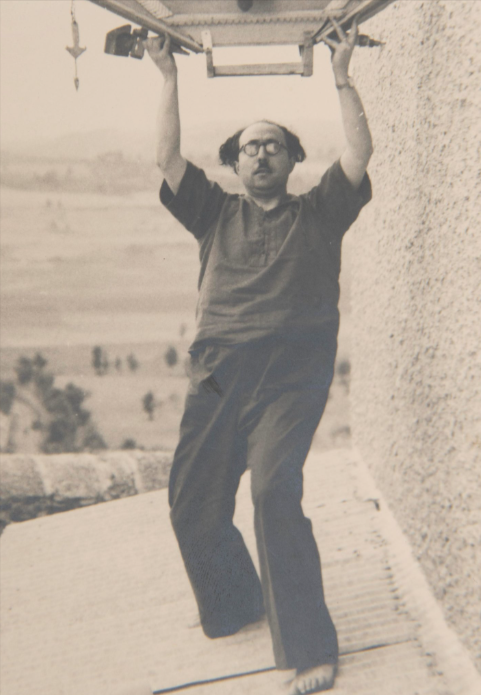

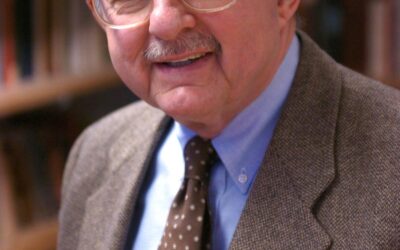

Peter Sloterdijk (born 1947) is a prominent German philosopher, cultural theorist, and public intellectual known for his innovative and provocative ideas on a wide range of topics, from globalization and religion to art and technology. His work, which encompasses numerous books, essays, and media appearances, has had a significant impact on contemporary philosophical discourse, particularly in Europe. Sloterdijk’s thought is characterized by its interdisciplinary scope, its engagement with the history of ideas, and its critical examination of the present moment.

Key Points:

- Peter Sloterdijk is a prominent German philosopher and cultural theorist born in 1947.

- He is known for his innovative and provocative ideas on globalization, religion, art, and technology.

- Sloterdijk’s work is characterized by its interdisciplinary scope and engagement with the history of ideas.

- He developed the concept of anthropotechnics, which refers to techniques humans use to shape and transform themselves.

- The “Spheres” trilogy is one of his most significant works, exploring human civilization as a process of building and inhabiting spaces of meaning.

- Sloterdijk introduced the concepts of immunology and co-immunity in relation to human societies.

- He is a critic of globalization, viewing it as a disruptive and destabilizing force.

- Sloterdijk’s work often challenges established norms and conventions, provoking public debate.

- His ideas have implications for therapeutic practices, viewing them as forms of anthropotechnic intervention.

- Sloterdijk’s work has similarities with themes in cyberpunk science fiction.

Life and Career

Born in Karlsruhe, Germany in 1947, Sloterdijk studied philosophy, German studies, and history at the University of Munich and the University of Hamburg. He received his PhD in 1976 with a dissertation on the concept of autobiographical writing in Nietzsche. After working as a freelance writer and television host, Sloterdijk became a professor of philosophy and media theory at the University of Art and Design Karlsruhe in 1992. In 2001, he was appointed rector of the University of Art and Design Karlsruhe, a position he held until 2015.

Sloterdijk’s early works, such as Critique of Cynical Reason (1983) and Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche’s Materialism (1986), established his reputation as a bold and original thinker, willing to challenge established intellectual traditions and cultural norms. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Sloterdijk’s work took a more explicitly political turn, with books like Spheres trilogy (1998-2004), in which he developed a grand philosophical-historical narrative of human civilization as a process of building and inhabiting various “spheres” or spaces of meaning and protection.

Throughout his career, Sloterdijk has been a frequent presence in public debates in Germany and beyond, often stirring controversy with his unconventional views and provocative statements. Despite the sometimes polarizing nature of his interventions, Sloterdijk’s work has been widely translated and discussed internationally, cementing his status as one of the most influential and thought-provoking philosophers of our time.

Key Ideas

Anthropotechnics:

Central to Sloterdijk’s thought is the concept of anthropotechnics, which he develops in works like You Must Change Your Life (2009). Anthropotechnics refers to the various techniques and practices through which human beings shape and transform themselves, both individually and collectively. For Sloterdijk, the history of human civilization can be understood as a series of anthropotechnic revolutions, from the ascetic practices of ancient philosophers and religious mystics to the self-optimization strategies of contemporary biohackers and transhumanists. Sloterdijk argues that in the face of the existential challenges posed by globalization and technological change, the question of how to consciously shape and improve ourselves has become more urgent than ever.

Spheres and Spaces:

Another key theme in Sloterdijk’s work is the importance of spatial metaphors and concepts for understanding human existence. In his monumental Spheres trilogy, Sloterdijk offers a sweeping history of human civilization as a process of building and inhabiting various “spheres” or spaces of meaning, from the intimate microspheres of the womb and the family to the macrospheres of nations, empires, and global networks. For Sloterdijk, human beings are fundamentally “sphere-building” creatures, who construct and dwell within various symbolic and material spaces that shape their sense of self and their relations to others.

Immunology and Co-Immunity:

Closely related to his concept of spheres, Sloterdijk’s notion of immunology refers to the various strategies and mechanisms through which human beings protect and defend themselves against external threats and dangers. Drawing on biological and medical metaphors, Sloterdijk argues that human societies can be understood as complex “immune systems,” which seek to create and maintain spaces of safety, meaning, and belonging in the face of an often hostile and uncertain world. In recent years, Sloterdijk has developed this idea further with the concept of “co-immunity,” which emphasizes the importance of shared spaces and collective practices for building resilience and solidarity in the face of global crises.

Globalization and “Monstrous Births”:

Throughout his work, Sloterdijk has been a trenchant critic of the processes and effects of globalization, which he sees as a fundamentally disruptive and destabilizing force. In books like In the World Interior of Capital (2005), he argues that globalization has created a new kind of “monstrous” space, in which traditional distinctions between inside and outside, self and other, have broken down. For Sloterdijk, the challenge of the present moment is to find new ways of creating and inhabiting meaningful spaces in the face of these “monstrous births,” whether through the revitalization of local communities and traditions or the invention of new forms of global solidarity and cooperation.

Critique and Provocation:

Finally, a defining feature of Sloterdijk’s intellectual style is his willingness to challenge and provoke established norms and conventions, both in his writing and in his public interventions. Whether critiquing the cynicism of contemporary media culture, defending the importance of elitism and excellence in education, or calling for a new kind of “anthropotechnic” politics, Sloterdijk has consistently sought to shake up and stimulate public debate, even at the risk of controversy and misunderstanding. In this sense, his work can be seen as a kind of philosophical “therapy,” which aims to diagnose and treat the pathologies of the present moment through critical reflection and creative experimentation.

Anthropotechnics and Therapeutic Practices

Sloterdijk’s concept of anthropotechnics offers a rich and suggestive framework for thinking about the role of therapeutic practices in shaping human subjectivity and experience. If anthropotechnics refers to the various techniques and practices through which human beings shape and transform themselves, then therapy can be understood as a particularly powerful and intensive form of anthropotechnic intervention, one that aims to effect deep and lasting changes in the way individuals relate to themselves and the world around them.

From this perspective, therapeutic practices like VR therapy, brainspotting, and ETT (Emotional Transformation Therapy) can be seen as contemporary examples of anthropotechnic innovation, which seek to harness the power of technology and scientific knowledge to facilitate personal growth and transformation. VR therapy, for example, uses immersive virtual reality environments to help individuals confront and overcome phobias, anxiety disorders, and other mental health challenges. By creating carefully controlled and customized virtual spaces, VR therapy allows individuals to safely and gradually expose themselves to feared stimuli, while learning new coping strategies and ways of relating to their emotions.

Similarly, brainspotting and ETT are therapeutic techniques that aim to access and transform deep-seated emotional and physiological patterns through targeted interventions in the body and the brain. Brainspotting uses eye positions and other somatic cues to locate and process unresolved trauma and stress, while ETT combines light hue, light direction, and flicker rates, and sound to facilitate emotional healing and integration. Like VR therapy, these techniques can be understood as forms of anthropotechnic practice, which use specialized knowledge and technology to shape and reshape human experience at a fundamental level.

At the same time, Sloterdijk’s work also highlights the potential risks and limitations of anthropotechnic interventions, including therapeutic ones. His critique of the “monstrous” spaces of globalization, for example, suggests that the very technologies and practices that are meant to enhance human well-being and flourishing can also have unintended and destructive consequences, by eroding traditional forms of meaning and belonging and creating new forms of dislocation and alienation. In the context of therapy, this might mean being attentive to the ways in which even well-intentioned interventions can sometimes reinforce problematic norms and expectations, or create new forms of dependency and disempowerment.

Moreover, Sloterdijk’s emphasis on the importance of shared spaces and collective practices for building resilience and solidarity suggests that individual therapeutic interventions alone may not be sufficient for addressing the deeper social and structural causes of mental health challenges. From this perspective, truly transformative anthropotechnic practices would need to go beyond the individual level to create new forms of community and co-immunity, which can support and sustain personal growth and well-being in the face of wider social and cultural pressures.

In this sense, engaging with Sloterdijk’s work can help to situate therapeutic practices like VR therapy, brainspotting, and ETT within a broader philosophical and political context, one that recognizes both their transformative potential and their limitations. By understanding therapy as a form of anthropotechnic intervention, we can begin to ask deeper questions about the ways in which these practices shape and reshape human subjectivity, and about the kinds of spaces and relationships they create and sustain. At the same time, Sloterdijk’s work challenges us to think beyond the individual level, and to consider how therapeutic practices can be integrated into wider projects of social and cultural transformation, ones that aim to create more resilient, equitable, and flourishing forms of human existence.

Anthropotechnics as a Form of Therapy

By understanding therapy as a form of anthropotechnic intervention, we can begin to appreciate its transformative potential in shaping human subjectivity and experience. Therapy, from this perspective, is not merely a means of alleviating symptoms or resolving conflicts but a powerful tool for reshaping the very fabric of the self. Through various techniques and practices, such as dialogue, reflection, exposure, and embodiment, therapy aims to help individuals develop new ways of relating to their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and to cultivate more flexible and adaptive patterns of being in the world. In this sense, therapy can be seen as a kind of “technology of the self,” a set of practices and procedures through which individuals can work on themselves, challenge limiting beliefs and habits, and expand their capacities for growth and flourishing. At the same time, understanding therapy as an anthropotechnic intervention also highlights its embeddedness within broader social, cultural, and political contexts, and the need to consider how therapeutic practices both reflect and shape the values, norms, and power relations of the wider world. Ultimately, the anthropotechnic perspective invites us to approach therapy with a spirit of curiosity and experimentation, as a space for exploring and transforming the endless possibilities of human becoming.

The Intuition and Predictions

Peter Sloterdijk’s work is not only philosophically rich but also culturally prescient, as he has anticipated and analyzed many of the key trends and challenges of our time. In particular, his ideas about globalization, technology, and the transformation of human existence bear a striking resemblance to the themes and motifs of the cyberpunk genre in science fiction.

Cyberpunk, which emerged in the 1980s with works like William Gibson’s Neuromancer, is characterized by its dystopian vision of a future world dominated by corporate power, technological alienation, and the blurring of boundaries between the human and the machine. In many ways, the cyberpunk imagination can be seen as a cultural expression of the very processes and tendencies that Sloterdijk analyzes in his work, from the erosion of traditional forms of identity and belonging to the rise of new forms of technological mediation and control.

For example, Sloterdijk’s concept of “monstrous births,” which he uses to describe the disruptive and destabilizing effects of globalization, finds a powerful echo in the cyberpunk trope of the “megacity,” the vast and chaotic urban sprawl that serves as the backdrop for many cyberpunk stories. In both cases, what is being described is a world in which traditional forms of social and spatial organization have broken down, giving rise to new and often threatening forms of complexity and interconnectedness.

Similarly, Sloterdijk’s notion of anthropotechnics, which refers to the various techniques and practices through which human beings shape and transform themselves, resonates strongly with the cyberpunk fascination with bodily modification and enhancement. From genetic engineering and cybernetic implants to virtual reality and drug-induced states of consciousness, cyberpunk is full of characters who use technology to alter and augment their physical and mental capacities, often in pursuit of power, pleasure, or escape from the constraints of ordinary reality.

At the same time, Sloterdijk’s work also points to the potential dangers and limitations of such anthropotechnic interventions, which can just as easily be used for purposes of control and domination as for liberation and empowerment. This ambivalence is also a key theme in cyberpunk, which often portrays technology as a double-edged sword, capable of both expanding and constricting human freedom and agency.

Trauma and Implicit Memory

One area where Sloterdijk’s concept of anthropotechnics could have particularly important implications is in the treatment of trauma and the transformation of implicit memory. Trauma, which can be understood as an overwhelming experience that exceeds an individual’s capacity to cope and integrate, often leaves deep and lasting imprints on the mind and body, shaping a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in ways that can be difficult to understand or control.

Much of the impact of trauma is mediated through implicit memory, which refers to the nonconscious, automatic, and affective processes that underlie our habitual ways of perceiving, thinking, and acting. Unlike explicit memory, which involves the conscious recollection of specific events and experiences, implicit memory operates largely outside of awareness, shaping our responses to the world in subtle but powerful ways.

From an anthropotechnic perspective, the challenge of treating trauma and transforming implicit memory can be understood as a challenge of reshaping the deep patterns and habits of the mind and body, which have been shaped by past experiences of overwhelming stress and distress. This might involve the use of various techniques and practices, such as body-oriented therapies, mindfulness and meditation, or exposure-based interventions, which aim to help individuals develop new ways of relating to their thoughts, feelings, and sensations.

At the same time, Sloterdijk’s work also suggests that truly transformative anthropotechnic interventions would need to go beyond the individual level to address the wider social and cultural contexts that shape and sustain traumatic experiences. This might involve efforts to create more supportive and inclusive communities, to challenge and change the power structures and ideologies that perpetuate violence and oppression, and to foster new forms of collective resilience and healing.

In this sense, the anthropotechnic approach to trauma and implicit memory would not only aim to help individuals cope with the aftermath of overwhelming experiences but also to create the conditions for a more just and equitable society, one that is less prone to generating traumatic experiences in the first place. This is a vision that is also present in some strands of cyberpunk fiction, which imagine alternative forms of social and technological organization that are more responsive to human needs and desires.

Timeline of Peter Sloterdijk’s Life

1947: Born on June 26 in Karlsruhe, Germany. 1968-1974: Studies philosophy, German studies, and history at the University of Munich. 1975: Completes his PhD at the University of Hamburg with a dissertation on autobiographical writing in Nietzsche. 1980s: Works as a freelance writer and television host, publishing his first major works, including “Critique of Cynical Reason” (1983) and “Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche’s Materialism” (1986). 1992: Becomes Professor of Philosophy and Media Theory at the University of Art and Design Karlsruhe. 2001: Appointed as Rector of the University of Art and Design Karlsruhe, a position he holds until 2015. 2002: Receives the Ernst Robert Curtius Prize for Essay Writing. 2005: Awarded the Sigmund Freud Prize for Scientific Prose. 2008: Receives the Lessing Prize for Criticism. 2012: Becomes a member of the Academy of Arts, Berlin. 2016: Retires from his position as Professor at the University of Art and Design Karlsruhe.

Philosophy

Peter Sloterdijk’s Major Publications

1983: “Critique of Cynical Reason” (Kritik der zynischen Vernunft) 1986: “Thinker on Stage: Nietzsche’s Materialism” (Der Denker auf der Bühne. Nietzsches Materialismus) 1988: “Critique of Aesthetic Reason” (Kritik der ästhetischen Urteilskraft) 1998-2004: “Spheres” trilogy (Sphären-Trilogie)

- 1998: “Bubbles” (Blasen)

- 1999: “Globes” (Globen)

- 2004: “Foam” (Schäume) 2001: “On the Improvement of the Good News: Nietzsche’s Fifth ‘Gospel'” (Über die Verbesserung der guten Nachricht: Nietzsches fünftes ‘Evangelium’) 2005: “In the World Interior of Capital: For a Philosophical Theory of Globalization” (Im Weltinnenraum des Kapitals: Für eine philosophische Theorie der Globalisierung) 2006: “Rage and Time: A Psychopolitical Investigation” (Zorn und Zeit. Politisch-psychologischer Versuch) 2009: “You Must Change Your Life: On Anthropotechnics” (Du mußt dein Leben ändern. Über Anthropotechnik) 2010: “Philosophical Temperaments: From Plato to Foucault” (Philosophische Temperamente. Von Platon bis Foucault) 2011: “Stress and Freedom” (Streß und Freiheit) 2013: “In the Shadow of Mount Sinai: A Footnote on the Origins and Changing Forms of Total Membership” (Im Schatten des Sinai: Fußnote über Ursprünge und Wandlungen totaler Mitgliedschaft) 2014: “After God” (Nach Gott) 2016: “Not Saved: Essays after Heidegger” (Nicht gerettet: Versuche nach Heidegger) 2018: “What Happened in the 20th Century? Towards a Critique of Extremist Reason” (Was geschah im 20. Jahrhundert? Unterwegs zu einer Kritik der extremistischen Vernunft) 2020: “Den Himmel zum Sprechen bringen: Elemente der Theopoesie” (Bringing the Sky to Speech: Elements of Theopoetics

Bibliography:

- Sloterdijk, P. (1983). Critique of Cynical Reason. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Sloterdijk, P. (1998-2004). Spheres trilogy. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

- Sloterdijk, P. (2005). In the World Interior of Capital: For a Philosophical Theory of Globalization. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Sloterdijk, P. (2009). You Must Change Your Life: On Anthropotechnics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Elden, S., & Mendieta, E. (Eds.). (2009). The Sloterdijk Reader. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

0 Comments