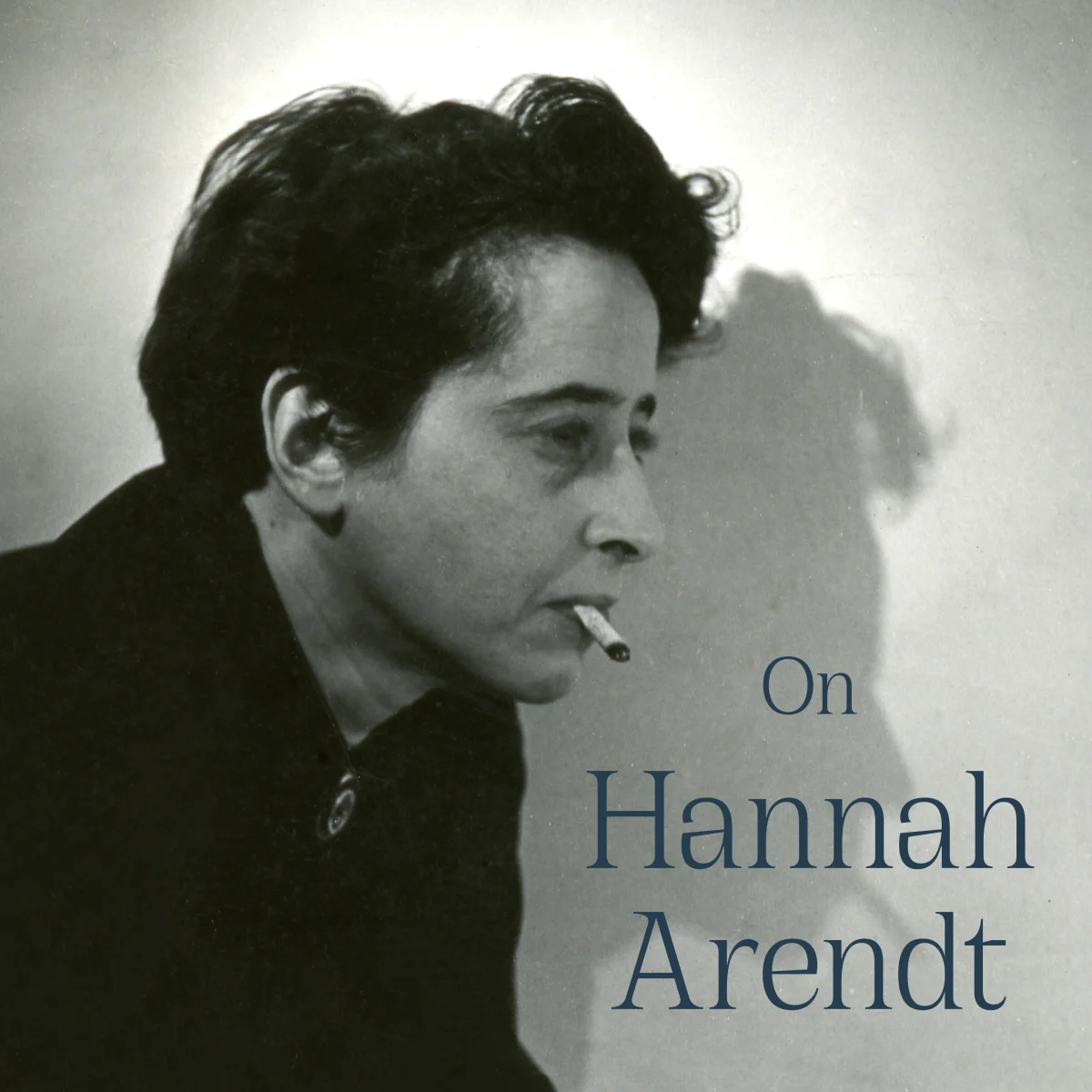

Who was Hannah Arendt:

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was a political philosopher and theorist whose influential work examined the human condition, the nature of political action, and the origins of totalitarianism. Her ideas have had a profound impact across disciplines, including psychology, politics, and design.

At the core of Arendt’s philosophy is her concept of the “vita activa” – the active life composed of three fundamental human activities: labor, work, and action. For Arendt, action is the most essential and political of these activities, as it allows humans to manifest their unique individuality and create new realities through interaction with others. In her seminal work The Human Condition, Arendt explores the distinction between the private and public realms, arguing that the erosion of the public sphere in modern society has led to the “rise of the social” – a domain that blurs the lines between private and public and stifles genuine political action. This concept has important implications for psychology, as it suggests that the privatization of human experience can inhibit individuals from fully realizing their potential as political beings. Arendt’s theories on totalitarianism, developed in her book The Origins of Totalitarianism, have also had a significant impact on political thought. Her analysis of the conditions that gave rise to totalitarian regimes in the 20th century, such as the breakdown of traditional political structures and the manipulation of mass society, offers insights into the nature of power, authority, and the challenges facing democratic societies. In the realm of design, Arendt’s emphasis on the public sphere and the role of human action in shaping the material world has influenced thinkers and practitioners who seek to create spaces and artifacts that foster civic engagement and political participation. Her concept of “world-building” – the human capacity to create and inhabit shared spaces – has been particularly influential in the fields of urban planning, architecture, and interaction design.

Why is Hannah Arendt Relevant?

Hannah Arendt’s philosophical work has had a profound impact on various fields, from political theory and philosophy to design and the humanities. Her distinction between labor, work, and action in the vita activa highlights the different ways in which humans engage with the world, with labor focusing on biological necessities, work on the creation of durable objects, and action on the political realm of speech and deed. This framework has been applied to fields such as sociology, economics, and urban planning to better understand human activities and their societal implications. Arendt’s analysis of the public/private distinction and the rise of the social realm has shed light on the blurring boundaries between personal and political life, influencing discussions in fields like media studies, gender studies, and public policy.

Hannah Arendt’s philosophical work has had a profound impact on various fields, from political theory and philosophy to design and the humanities. Her distinction between labor, work, and action in the vita activa highlights the different ways in which humans engage with the world, with labor focusing on biological necessities, work on the creation of durable objects, and action on the political realm of speech and deed. This framework has been applied to fields such as sociology, economics, and urban planning to better understand human activities and their societal implications. Arendt’s analysis of the public/private distinction and the rise of the social realm has shed light on the blurring boundaries between personal and political life, influencing discussions in fields like media studies, gender studies, and public policy.

Arendt’s groundbreaking work on totalitarianism has provided insights into the mechanisms of oppressive regimes and the conditions that enable their rise, informing research in political science, history, and international relations. Her concept of the “banality of evil,” which emerged from her coverage of the Eichmann trial, has challenged traditional notions of moral responsibility and has been applied to the study of mass atrocities, organizational behavior, and psychology. Arendt’s emphasis on natality and the human capacity for new beginnings has inspired work in fields such as education, social entrepreneurship, and activism, highlighting the transformative potential of human action.

Her insights into storytelling and the narrativity of human experience have influenced the fields of literature, history, and anthropology, underscoring the importance of narrative in shaping individual and collective identities. Finally, Arendt’s concept of “world-building” has found resonance in the fields of architecture, urban design, and material culture studies, emphasizing the role of human-made objects and spaces in creating a shared world. Overall, Arendt’s interdisciplinary approach and wide-ranging ideas continue to inspire scholars and practitioners across various fields, offering a rich framework for understanding the complexities of the human condition and the world we inhabit.

What were Hannah Arendt’s Major Theories?

1. The vita activa and the distinction between labor, work, and action:

Hannah Arendt’s concept of the vita activa is a fundamental aspect of her philosophical thought, which she develops in her book “The Human Condition.” The vita activa encompasses three distinct human activities: labor, work, and action. Labor refers to the biological processes and necessities that are essential for the maintenance of human life. This includes activities such as eating, drinking, sleeping, and reproducing. Labor is characterized by its cyclical nature and its focus on the fulfillment of basic needs. It is the realm of the animal laborans, the human being as a creature of nature. Work, in contrast, involves the creation of durable objects and artifacts that constitute the human-made world. This includes the production of tools, buildings, artworks, and other objects that have a degree of permanence and stability. Work is the domain of homo faber, the human being as a maker and fabricator.

It is through work that humans create a world that is distinct from the natural environment and that provides a context for human existence. Action, the highest form of the vita activa, is the political activity of speech and deed. It occurs between individuals in the public realm and has the potential to initiate new beginnings. Action is the realm of plurality, where humans interact with one another as unique individuals. It is through action that humans reveal their distinctiveness and create a web of human relationships. Action is inherently unpredictable and irreversible, as it sets in motion processes that cannot be fully controlled or undone. Arendt’s distinction between labor, work, and action provides a framework for understanding the different ways in which humans engage with the world. It highlights the importance of creating a durable, human-made world through work, while also emphasizing the significance of political action and the public realm. At the same time, Arendt recognizes the necessity of labor for the maintenance of life, even as she argues that it should not be the sole focus of human existence. The vita activa thus offers a rich and nuanced perspective on the human condition and the various activities that shape our lives.

2. The public/private distinction and the rise of the social realm:

Arendt’s distinction between the public and private realms is another key aspect of her political thought. For Arendt, the public realm is the space of appearance, where individuals come together to engage in political speech and action. It is the domain of freedom, where humans can reveal their unique identities and create a shared world. The public realm is characterized by plurality, equality, and the potential for new beginnings. In contrast, the private realm is the sphere of the household, which is concerned with the necessities of life. It is the domain of the family, where individuals are bound together by their common needs and desires. The private realm is characterized by inequality, as it is based on the hierarchical relations between masters and slaves, men and women. Arendt argues that the rise of the social realm in the modern age has blurred the boundaries between the public and private spheres. The social realm is a hybrid space that combines elements of both the public and private realms. It is concerned with the collective management of the necessities of life, such as economic production and consumption. The social realm is characterized by conformity, bureaucracy, and the prioritization of economic concerns over political action.

For Arendt, the rise of the social realm poses a threat to both the public and private spheres. It leads to the erosion of the public realm, as political action is replaced by the administration of social and economic processes. At the same time, it undermines the privacy and intimacy of the household, as the private realm becomes increasingly subject to public scrutiny and control. Arendt’s analysis of the public/private distinction and the rise of the social realm has important implications for contemporary political and social life. It highlights the need to preserve and strengthen the public realm as a space for political action and freedom, while also recognizing the importance of privacy and the household. It calls into question the increasing dominance of economic and social concerns over political life, and the erosion of the boundaries between the public and private spheres. Arendt’s insights thus provide a valuable framework for critiquing and reimagining the political and social structures of the modern world.

3. The origins and nature of totalitarianism:

In her seminal work “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” Hannah Arendt provides a comprehensive analysis of the rise of totalitarian regimes in the 20th century. She examines the historical, social, and political factors that contributed to the emergence of Nazism in Germany and Stalinism in the Soviet Union, and identifies the key characteristics of totalitarian rule. Arendt argues that totalitarianism is a novel form of government that seeks to dominate all aspects of human life and to eliminate human plurality and spontaneity. Totalitarian regimes are characterized by their use of ideology, terror, and the destruction of the public realm. They rely on the creation of a fictitious world, in which reality is replaced by a fabricated narrative that justifies the regime’s actions and policies. One of the key elements of totalitarianism is the use of ideology as a means of mobilizing the masses and justifying the regime’s rule. Totalitarian ideologies, such as Nazism and Stalinism, claim to have discovered the laws of history or nature, and to be able to create a perfect society through the application of these laws. They demand total loyalty and obedience from their followers, and seek to eliminate all forms of dissent or opposition.

Another essential feature of totalitarianism is the use of terror as a means of control and domination. Totalitarian regimes create a climate of fear and suspicion, in which individuals are constantly monitored and punished for any deviation from the official ideology. The concentration camp system, which was a central feature of both Nazism and Stalinism, serves as a paradigmatic example of the use of terror to destroy human individuality and create a society of atomized, isolated individuals. Arendt also emphasizes the role of the destruction of the public realm in the rise of totalitarianism. Totalitarian regimes seek to eliminate all forms of spontaneous human interaction and association, and to replace them with state-controlled organizations and movements. They destroy the institutions and spaces that allow for political action and the creation of a shared world, such as political parties, trade unions, and independent media. Arendt’s analysis of totalitarianism has had a profound impact on political theory and practice. It has provided a framework for understanding the dangers of ideological fanaticism, the importance of preserving human plurality and spontaneity, and the need to protect the public realm from the encroachment of totalitarian tendencies. Her insights continue to be relevant in the contemporary world, as we grapple with the challenges posed by authoritarianism, populism, and the erosion of democratic norms and institutions.

4. The concept of the “banality of evil” and its implications for human moral responsibility:

Hannah Arendt’s concept of the “banality of evil” emerged from her coverage of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi bureaucrat who played a central role in the implementation of the Holocaust. Eichmann was captured by Israeli agents in Argentina in 1960 and brought to Jerusalem to stand trial for his crimes. Arendt, who attended the trial as a correspondent for The New Yorker, was struck by Eichmann’s apparent ordinariness and lack of malevolent intent. In her book “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,” Arendt argues that Eichmann was not a sadistic monster or a fanatical anti-Semite, but rather a mediocre bureaucrat who unthinkingly followed orders and adhered to the norms of his organization. Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil challenges traditional notions of moral responsibility and the nature of evil itself. It suggests that evil can arise not only from malicious intent or sadistic cruelty, but also from thoughtlessness, conformity, and the failure to reflect on one’s actions. Eichmann, in Arendt’s view, was not a demon or a monster, but rather a “terrifyingly normal” individual who failed to think critically about the consequences of his actions and the moral implications of his choices. The banality of evil has important implications for our understanding of moral responsibility and the prevention of atrocities. It suggests that ordinary people, under certain conditions, can participate in acts of great evil without necessarily being motivated by hatred or sadism. It highlights the dangers of conformity, obedience to authority, and the abdication of personal responsibility in the face of bureaucratic and organizational pressures.

At the same time, the banality of evil does not absolve individuals of moral responsibility for their actions. Arendt emphasizes that Eichmann, despite his apparent ordinariness, made choices and bore responsibility for the consequences of his actions. She argues that the failure to think critically and to exercise moral judgment is itself a form of moral failure, and that individuals have a responsibility to resist the pressures of conformity and to act in accordance with their conscience. The concept of the banality of evil has had a significant impact on discussions of moral responsibility, the psychology of perpetrators, and the prevention of atrocities. It has been applied to a wide range of contexts, from corporate malfeasance and political corruption to war crimes and genocide. It has also been the subject of much debate and criticism, with some arguing that it downplays the role of ideology and individual agency in the commission of atrocities. Despite these debates, the banality of evil remains an important and provocative concept that challenges us to think deeply about the nature of moral responsibility and the conditions that enable ordinary people to participate in acts of great evil. It reminds us of the importance of critical thinking, personal responsibility, and the cultivation of moral courage in the face of bureaucratic and organizational pressures. As such, it continues to be a valuable resource for those seeking to understand and prevent the atrocities that have marked human history.

5. The role of natality and the capacity for new beginnings in political action:

Hannah Arendt’s concept of natality is a central theme in her political thought, and refers to the human capacity to initiate new beginnings and to act in unexpected ways. For Arendt, natality is the fundamental condition of human existence, and is the source of our ability to create new possibilities and to shape the world through our actions. Arendt argues that each human birth represents a new beginning, a potential for novelty and unpredictability that is inherent in the human condition. Every new human being who comes into the world has the capacity to act in ways that are not predetermined by their social or historical circumstances, and to initiate new processes and events that can change the course of history. This capacity for new beginnings is particularly important in the realm of political action, which Arendt sees as the highest form of human activity. Political action, for Arendt, is the activity of engaging in public discourse and debate, of forming opinions and making decisions that affect the common world. It is through political action that humans can create a shared reality and a sense of meaning and purpose in their lives. Natality is essential for political action because it allows for the possibility of change and transformation. If humans were entirely determined by their social and historical circumstances, there would be no room for genuine political action or the creation of new possibilities. But because each new human being has the capacity to act in unexpected ways and to initiate new beginnings, there is always the potential for political change and renewal.

Arendt’s concept of natality has important implications for our understanding of political agency and the role of individuals in shaping the world. It suggests that even in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles and entrenched power structures, individuals have the capacity to act in ways that can make a difference and create new possibilities for the future. At the same time, Arendt recognizes that the capacity for new beginnings is not unlimited, and that political action is always constrained by the conditions of the world in which it takes place. She emphasizes the importance of creating and preserving a stable and durable world, a common reality that can provide a context for human action and interaction. Arendt’s insights into the role of natality and the capacity for new beginnings in political action continue to be relevant in the contemporary world. They remind us of the importance of individual agency and the potential for political change, even in the face of seemingly intractable problems and entrenched power structures. They also highlight the need to create and preserve a common world, a shared reality that can provide a context for human action and interaction, and to resist the forces that seek to undermine or destroy it.

6. The importance of storytelling and the narrativity of human experience:

Hannah Arendt’s emphasis on the importance of storytelling and the narrativity of human experience is a key theme in her philosophical and political thought. For Arendt, storytelling is not merely a form of entertainment or a way of passing down cultural traditions, but is an essential aspect of the human condition that shapes our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Arendt argues that human beings are fundamentally storytelling creatures, and that our sense of identity and meaning is inextricably tied to the stories we tell about ourselves and our place in the world. These stories can take many forms, from personal narratives and family histories to cultural myths and political ideologies. One of the key functions of storytelling, according to Arendt, is to create a sense of continuity and coherence in the face of the flux and contingency of human experience. By weaving together the disparate events and experiences of our lives into a narrative structure, we are able to create a sense of meaning and purpose that can guide our actions and shape our sense of self.

Storytelling is also essential for creating a shared world and a sense of common reality. By telling stories about our experiences and the events that shape our lives, we are able to communicate with others and to create a shared understanding of the world. This is particularly important in the realm of politics, where the ability to tell compelling stories and to shape public narratives is essential for building coalitions and mobilizing support for political action. Arendt’s emphasis on the narrativity of human experience has important implications for our understanding of history and the role of individuals in shaping the course of events. She argues that history is not a simple chronicle of events or a deterministic process, but is shaped by the stories that individuals and communities tell about themselves and their place in the world. This means that individuals have the power to shape the course of history through the stories they tell and the actions they take. By creating new narratives and challenging dominant ideologies, individuals can create new possibilities for the future and shape the world in ways that reflect their values and aspirations.

At the same time, Arendt recognizes that storytelling can also be used to justify oppression and violence, and to create false narratives that obscure the reality of human suffering. She emphasizes the importance of critical thinking and the need to interrogate the stories we tell about ourselves and the world, in order to uncover the hidden assumptions and power structures that shape our understanding of reality. Arendt’s insights into the importance of storytelling and the narrativity of human experience continue to be relevant in the contemporary world. They remind us of the power of stories to shape our sense of identity and meaning, and to create a shared world and a sense of common reality. They also highlight the need for critical thinking and the importance of interrogating the stories we tell, in order to uncover the hidden assumptions and power structures that shape our understanding of the world.

7. The concept of “world-building” and its relevance to design and the material world:

Hannah Arendt’s concept of “world-building” is a central theme in her philosophical and political thought, and refers to the human capacity to create and sustain a durable, shared world through the production of artifacts, institutions, and spaces. For Arendt, world-building is not merely a matter of creating physical objects or structures, but is an essential aspect of the human condition that shapes our sense of reality and our ability to live together in a common world. Arendt argues that the world is not a natural given, but is a human artifact that is created through the collective efforts of individuals and communities. This world-building activity takes many forms, from the creation of tools and technologies to the construction of buildings and cities, and from the establishment of laws and institutions to the production of works of art and culture.

One of the key functions of world-building, according to Arendt, is to create a stable and durable context for human existence and interaction. By creating a world of objects and structures that endure over time, we are able to establish a sense of permanence and continuity in the face of the flux and contingency of human experience. This world provides a common reality that we can share with others, and a context for our actions and interactions. Arendt’s concept of world-building has important implications for the fields of design, architecture, and urban planning, as it highlights the role of human-made objects and environments in shaping our lived experiences and collective life. It suggests that designers and planners have a responsibility not merely to create functional or aesthetically pleasing objects and spaces, but to contribute to the creation of a shared world that can sustain human existence and interaction over time.

This means that designers and planners must consider not only the immediate needs and desires of individuals and communities, but also the long-term implications of their work for the creation and preservation of a common world. They must strive to create objects and environments that are not merely functional or efficient, but that also have a sense of permanence and durability, and that can contribute to the establishment of a shared reality and a sense of place. At the same time, Arendt’s concept of world-building also highlights the importance of public space and the public realm for the creation and maintenance of a common world. She argues that the public realm is essential for the creation of a shared reality and a sense of common purpose, and that the erosion of public space and the public sphere in modern society threatens the very foundations of our common world.

This means that designers and planners must also consider the role of public space and the public realm in their work, and strive to create environments that foster social interaction, civic engagement, and the creation of a shared sense of community. They must resist the temptation to privatize public space or to create environments that are merely functional or efficient, but that do not contribute to the creation of a shared world and a sense of place.

Hannah Arendt’s Influence on Art:

Arendt’s philosophical ideas have had a profound impact on our understanding of the nature of artistic work and the relationship between the artist, the artwork, and the audience. While she did not directly address the realm of art and aesthetics, her insights into plurality, the public realm, and the human condition resonate deeply with the notion of the artist as a unique voice expressing their distinctive perspective and experience.

Arendt’s celebration of natality, the capacity to initiate new beginnings and introduce novelty into the world, aligns with the artist’s ability to create something original and unprecedented through their work. Furthermore, her conception of action as the highest human endeavor, through which individuals reveal their unique identities, resonates with the understanding of artistic creation as a form of action – where the artist inserts themselves into the human web of relationships and leaves their indelible mark on the world.

Arendt’s emphasis on the public realm as a space for discourse and collective action has significant implications for the role of the audience in the artistic experience. The artwork becomes a catalyst for dialogue, interpretation, and the exchange of diverse perspectives, fostering a sense of shared humanity and common understanding.

Moreover, Arendt’s notion of “worldliness” – the idea that humans are conditioned beings who construct and inhabit a shared world – highlights the capacity of art to shape and reflect the human experience. Artistic works can be understood as expressions of the human condition, inviting the audience to engage with and contemplate the complexities of our existence.

Arendt’s influence on the nature of artistic work and the artist-audience relationship lies in her recognition of the profound significance of human plurality, the importance of the public realm, and the capacity of human beings to create enduring works that transcend individual existence. Her ideas challenge us to understand art not merely as a form of self-expression or aesthetic appreciation but as a vital component of the human condition, contributing to the preservation of collective memory, fostering dialogue and understanding, and affirming the uniqueness and potential of each individual voice.

Hannah Arendt’s Influence on Architecture, New Urbanism and Design:

Arendt’s thought has had significant implications in various fields, including psychoanalysis, psychotherapy, architecture, and design. Her philosophical ideas and concepts have prompted reflections and discussions within these domains, challenging traditional notions and encouraging a more holistic approach to human experiences and social dynamics.

In psychoanalysis and psychotherapy, Arendt’s emphasis on the importance of human plurality, action, and the need for individuals to engage in meaningful self-expression and self-realization has resonated with perspectives that aim to foster personal growth, self-acceptance, and the ability to embrace new beginnings.

Moreover, her notion of “the space of appearance” – the public realm where individuals can reveal themselves through speech and action – has been explored in relation to the therapeutic encounter, where individuals have the opportunity to narrate their stories and engage in self-disclosure.

In architecture and design, Arendt’s conception of the “public realm” as a space for human interaction, discourse, and collective action has influenced architects and urban planners in their approach to designing spaces that foster community, engagement, and a sense of shared experience. Her emphasis on the durability and permanence of the human-made world has resonated with designers and architects who strive to create enduring structures that contribute to a sense of continuity and collective memory.

Furthermore, Arendt’s notion of “worldliness” – the idea that humans are conditioned beings who construct and inhabit a shared world – has been interpreted as a call for architecture and design to consider the human experience and to create spaces that facilitate human interactions, activities, and the formation of meaningful connections.

Architects and designers have drawn inspiration from Arendt’s ideas to create spaces that encourage active participation, promote dialogue, and foster a sense of belonging and community. Her concepts have challenged traditional notions of architecture as merely functional or aesthetic, and have encouraged a more holistic approach that considers the lived experiences and social dynamics of the people who inhabit and engage with the built environment.

Arendt’s influence extends beyond the realms of philosophy and political theory, as her insights continue to resonate and inspire interdisciplinary discussions and approaches across various fields. Her emphasis on the human condition, plurality, and the preservation of spaces for genuine human interaction and self-expression has prompted architects, designers, psychologists, and others to reconsider the ways in which their respective disciplines shape and reflect the lived experiences of individuals and communities.

Hannah Arendt’s Theories Applied to Trauma and Psychotherapy

Hannah Arendt, a prominent political philosopher of the 20th century, made significant contributions to our understanding of the human condition, totalitarianism, and the nature of evil. While her work primarily focused on political theory, her insights have far-reaching implications that extend beyond the realm of politics. In this blog post, we will delve into how Arendt’s ideas can be applied to the field of psychology, particularly in understanding trauma and its treatment through various psychotherapy approaches, such as Jungianism and Gestalt therapy.

Banality of Evil:

Arendt’s concept of the “banality of evil” is particularly relevant when considering the nature of trauma. In her groundbreaking work, “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,” Arendt covered the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi bureaucrat responsible for the deportation of millions of Jews to concentration camps during World War II. Through her observations, Arendt concluded that Eichmann was not a malevolent monster but rather an ordinary person who unthinkingly followed orders and failed to reflect on the moral consequences of his actions. This insight challenges the traditional notion that evil is perpetrated solely by inherently malicious individuals and suggests that trauma can arise from the thoughtless actions of ordinary people who fail to consider the impact of their behavior on others.

Recognizing the “banality of evil” in the context of trauma can help destigmatize survivors by highlighting that their experiences may not always be the result of intentional cruelty but rather the consequence of a broader systemic failure to prevent or address harmful actions. This understanding emphasizes the importance of addressing not only individual perpetrators but also the societal and institutional factors that enable traumatic experiences to occur.

Furthermore, Arendt’s ideas on storytelling and the narrativity of human experience are particularly relevant to the process of trauma recovery. In her work “The Human Condition,” Arendt emphasizes the importance of storytelling as a means of creating meaning and shared understanding. She argues that by sharing our stories, we can make sense of our experiences, find purpose, and connect with others who may have undergone similar struggles. This idea is especially pertinent in the context of trauma, where individuals often struggle to process and integrate their experiences into a coherent narrative.

Personal and Societal Storys

Psychotherapy, particularly approaches that emphasize the importance of narrative, such as narrative therapy, can play a crucial role in helping trauma survivors to reconstruct their stories in a way that promotes healing and growth. By providing a safe and supportive space for individuals to explore and reframe their experiences, therapists can help survivors to develop a more empowering and resilient sense of self. This process can involve challenging dominant societal narratives that may contribute to feelings of shame or self-blame, and instead focusing on the individual’s strengths, resilience, and capacity for healing.

Arendt’s ideas also have important implications for understanding trauma through the lens of depth psychology, particularly Jungian psychology. Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, emphasized the importance of the collective unconscious – a shared, universal repository of archetypes and symbols that shape human experience. Arendt’s concept of “world-building” – the idea that humans create shared meaning and a sense of reality through the construction of artifacts, institutions, and spaces – can be seen as analogous to Jung’s collective unconscious. Both concepts highlight the ways in which our individual experiences are shaped by larger, often unconscious, structures and patterns.

Trauma:

In the context of trauma, Jungian therapy may focus on exploring how an individual’s traumatic experiences are related to broader archetypal themes and patterns. By recognizing the ways in which their personal experiences are connected to universal human struggles, individuals may find a greater sense of meaning and purpose in their healing journey. Additionally, Arendt’s emphasis on natality – the human capacity for new beginnings – resonates with Jung’s concept of individuation, the process of becoming one’s authentic self. By embracing their potential for growth and transformation, individuals can transcend their traumatic experiences and create new, more fulfilling narratives for their lives.

Gestalt therapy, an experiential approach that emphasizes the importance of present-moment awareness and the holistic nature of human experience, can also benefit from incorporating Arendt’s ideas. Her distinction between labor, work, and action in the vita activa (active life) provides a useful framework for understanding the different dimensions of human experience. Labor refers to the biological processes necessary for survival, work involves the creation of durable objects and structures, and action encompasses the realm of human interaction and the capacity for new beginnings. By exploring how individuals engage with the world through these three spheres of activity, Gestalt therapists can help clients identify patterns and obstacles that may be contributing to their traumatic experiences.

Moreover, Arendt’s analysis of the blurring boundaries between the public and private realms, and the rise of the social sphere, can inform Gestalt therapy’s focus on the individual’s relationship to their environment. She argues that the modern era has seen a collapse of the traditional boundaries between the public and private spheres, leading to a loss of both individual privacy and genuine public discourse. In the context of trauma, this blurring of boundaries can contribute to a sense of vulnerability and a lack of control over one’s experiences. By examining how these societal shifts may be impacting clients’ lives, Gestalt therapists can help them develop new strategies for navigating their social worlds and asserting their autonomy.

In conclusion, Hannah Arendt’s philosophical insights offer valuable perspectives for understanding trauma and informing psychotherapeutic approaches. Her concept of the “banality of evil” challenges us to recognize the complex systemic factors that contribute to traumatic experiences, while her emphasis on storytelling and narrative highlights the importance of helping survivors to construct meaning and find connection through the sharing of their stories. Arendt’s ideas also resonate with key concepts in Jungian psychology, such as the collective unconscious and the process of individuation, and can inform Gestalt therapy’s focus on the holistic nature of human experience and the individual’s relationship to their environment. By drawing on these rich philosophical perspectives, psychotherapists can develop more nuanced and effective approaches to treating trauma and promoting healing and growth.

Hannah Arendt’s Life and Work

Timeline of Hannah Arendt’s Life

Hannah Arendt’s Publications:

“The Origins of Totalitarianism” 1951:

“The Origins of Totalitarianism” by Hannah Arendt is a profound and seminal work that examines the roots and emergence of totalitarian regimes in the 20th century. Published in 1951, this monumental study analyzes the historical and philosophical underpinnings of Nazism and Stalinism, two of the most oppressive and destructive political systems in modern history.

In this work, Arendt argues that totalitarianism is a novel and unprecedented form of government that emerged from the crisis of modernity. She traces its origins to a combination of factors, including the rise of anti-Semitism, imperialism, and the breakdown of traditional nation-states.

One of Arendt’s central arguments is that totalitarianism is not merely an extreme form of dictatorship or tyranny but a fundamentally new and unprecedented phenomenon. She argues that totalitarian regimes seek to control every aspect of human life, not just the political sphere, and to create a society based on an all-encompassing ideology that eliminates individuality and pluralism.

Arendt’s analysis delves into the historical roots of anti-Semitism and how it served as a crucial precursor to the rise of Nazism. She examines the role of imperialism and the emergence of the “superfluous” masses, those who were disconnected from traditional social and economic structures, and how these factors contributed to the appeal of totalitarian ideologies.

Furthermore, Arendt explores the concept of “loneliness as the basic experience of totalitarian terror.” She argues that totalitarian regimes systematically destroy human spontaneity, individuality, and the capacity for free thought and action, reducing individuals to mere cogs in a vast, dehumanizing machine.

One of the most significant contributions of “The Origins of Totalitarianism” is Arendt’s analysis of the nature of evil in the modern age. She challenges the traditional understanding of evil as stemming from human wickedness or moral depravity. Instead, she posits that the evil of totalitarianism arises from a combination of bureaucratic indifference, obedience to authority, and the normalization of violence and cruelty.

Arendt’s work has had a profound impact on political theory, philosophy, and our understanding of the modern world. Her insights into the nature of totalitarianism, the fragility of human freedom, and the importance of individual responsibility and critical thinking continue to resonate today, serving as a warning against the dangers of unchecked power, ideological conformity, and the erosion of democratic institutions.

“The Origins of Totalitarianism” remains a seminal work that has shaped our comprehension of the darkest chapters of the 20th century and continues to inspire scholars, intellectuals, and citizens alike to confront the enduring challenges of preserving human dignity, freedom, and the sanctity of individual life in the face of oppressive and dehumanizing forces.

The Human Condition 1958:

Hannah Arendt’s “The Human Condition” offers a profound exploration of the fundamental aspects that define the human experience and the complexities inherent to our existence. At its core, Arendt delves into the “vita activa” – the three essential human activities of labor, work, and action – and elevates action, the capacity for speech and deeds, as the quintessential human endeavor.

Through action, individuals assert their unique identities and affirm their existence within the shared world. This resonates with Arendt’s emphasis on plurality, the recognition of human diversity and the exchange of differing perspectives as vital for preserving freedom and fostering genuine interaction. The public realm emerges as the space where action and discourse can unfold, underscoring its pivotal role in nurturing human agency and self-expression.

Arendt’s critique of modernity’s prioritization of instrumental rationality and the diminishment of the public sphere serves as a cautionary tale, warning of the potential dehumanization that can arise when human beings are reduced to mere cogs in an impersonal system. This foreshadows her later explorations of the “banality of evil” and the dangers of thoughtless conformity.

Furthermore, “The Human Condition” introduces the concept of natality, the capacity to initiate new beginnings and introduce novelty into the world. This aligns with Arendt’s later emphasis on spontaneity and the need for individuals to embrace their potential for authentic self-realization and self-expression, ideas that would resonate in psychoanalytic and psychotherapeutic circles.

Throughout the work, Arendt challenges us to confront the inherent contradictions of our existence while celebrating the inherent dignity and potential of human beings to shape their collective destinies through responsible engagement with the world. This sets the stage for her subsequent works, which delve deeper into the complexities of political action, violence, and the preservation of democratic institutions.

“Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil” 1963:

In her controversial yet thought-provoking account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,” Arendt challenges conventional notions of evil and individual responsibility. Her concept of “the banality of evil” posits that the atrocities committed by individuals like Eichmann were not necessarily driven by deep-seated hatred or malice but by a disturbing lack of critical thinking, blind obedience to authority, and bureaucratic indifference to the consequences of their actions.

Arendt’s portrayal of Eichmann as an ordinary, seemingly unremarkable individual who was simply “doing his job” resonated as an unsettling reality – that evil can manifest through the thoughtless conformity and bureaucratic mentality that characterized the Nazi regime and other modern systems of oppression. This insight echoes her earlier critique in “The Human Condition” of the modern age’s emphasis on instrumental rationality and the erosion of spaces for genuine human agency and self-reflection.

Moreover, Arendt’s examination of the role of language and its manipulation in obscuring the true nature of oppressive actions highlights the importance of critical thinking and moral courage in resisting the forces of dehumanization. This aligns with her advocacy for preserving the public realm as a space for discourse and collective action, where individuals can assert their unique identities and challenge injustice.

The controversy surrounding “Eichmann in Jerusalem” underscores the profound discomfort Arendt’s ideas evoked, as they confronted deeply held assumptions about the nature of evil and the limits of individual responsibility. Yet, her intention was not to excuse or justify Eichmann’s actions but rather to confront the disturbing reality that evil can manifest through seemingly ordinary individuals operating within bureaucratic systems – a warning against the dangers of uncritical obedience and the erosion of human agency.

“On Revolution” 1963:

In “On Revolution,” Arendt offers a nuanced analysis of the concept of revolution, drawing insights from the American and French Revolutions. At the heart of her exploration is the distinction between “liberation” and “freedom,” where true freedom can only be achieved through the establishment of a new political order that enshrines participatory democracy and preserves public spaces for political action.

Arendt’s critique of the conflation of political and social questions resonates with her earlier emphasis on the importance of preserving the integrity of the public realm and the spaces for genuine political discourse. She warns against the erosion of these spaces by the encroachment of private interests and the prioritization of narrow economic concerns – a theme that would continue to resonate in her later work, “Crises of the Republic.”

Throughout “On Revolution,” Arendt emphasizes the importance of public spaces and the practice of political action as essential components of a truly free society. This echoes her earlier celebration of action in “The Human Condition” as the means through which individuals affirm their existence and shape their collective destinies. Her insights into the complexities of political change and the delicate balance between the pursuit of liberty and the preservation of a vibrant public realm continue to resonate in contemporary political discourse.

“On Violence” 1970:

In “On Violence,” Arendt offers a penetrating analysis of the nature and role of violence in the modern world, challenging conventional assumptions about the relationship between violence and power. Her distinction between violence as inherently instrumental and power as rooted in collective support and legitimacy aligns with her earlier emphasis on the importance of preserving the public realm and the spaces for genuine political action.

Arendt’s critique of the glorification and romanticization of violence within certain revolutionary and resistance movements echoes her earlier warnings about the dangers of unchecked and unrestrained forms of protest that can destabilize the foundations of the political order. Her advocacy for non-violent resistance and civil disobedience as true acts of courage resonates with her celebration of action as a means of affirming one’s unique identity and engaging in meaningful political discourse.

Throughout the work, Arendt emphasizes the importance of cultivating non-violent forms of resistance and creating robust institutions and processes for addressing grievances and resolving conflicts. This aligns with her earlier calls for preserving the integrity of the public realm and fostering spaces for genuine political action and discourse, where individuals can exercise their agency and collective power through legitimate means.

“Crises of the Republic” 1972:

In “Crises of the Republic,” Arendt offers a penetrating analysis of the political and social upheavals that gripped the United States in the 1960s, examining events such as the civil rights movement, anti-war protests, and the rise of counterculture movements through the lens of her unique philosophical perspective.

Arendt’s concern for the preservation of the public realm and the health of democratic institutions echoes her earlier writings on the importance of preserving spaces for genuine political action and discourse. Her critique of the tendency to conflate the social and political spheres resonates with her earlier warnings against the erosion of the public realm by the encroachment of private interests and the prioritization of narrow economic concerns.

Throughout the work, Arendt emphasizes the importance of fostering robust political discourse and safeguarding the principles of republican governance in the face of societal upheavals and challenges. This aligns with her earlier calls for preserving the integrity of the public realm and the spaces for collective action, where individuals can assert their unique identities and engage in meaningful political discourse.

“The Life of the Mind” 1978 (Published Posthumously):

In “The Life of the Mind,” Arendt’s ambitious exploration of the fundamental human faculties of thinking, willing, and judging, she continues her pursuit of understanding the nature of human existence and the capacity for moral and ethical action.

Arendt’s analysis of thinking as an internal dialogue with oneself resonates with her earlier emphasis on the importance of self-reflection and the ability to question assumptions – a bulwark against the forces of totalitarianism, conformity, and the erosion of human dignity. Her critique of the modern age’s emphasis on instrumental rationality and the prioritization of means over ends echoes her earlier warnings about the potential dehumanization that can arise when human beings are reduced to mere cogs in an impersonal system.

Arendt’s exploration of the faculty of willing and the nature of human agency builds upon her earlier work in “The Human Condition,” where she examined the relationship between thinking and acting, and the role of the will in translating thought into deed. This aligns with her celebration of action as the means through which individuals affirm their existence and shape their collective destinies.

Moreover, Arendt’s unfinished exploration of the faculty of judging, and its importance in navigating moral and ethical dilemmas, resonates with her earlier emphasis on the preservation of the public realm as a space for discourse and the exchange of diverse perspectives – a means of fostering a sense of shared humanity and common understanding.

Throughout her body of work, Arendt’s unwavering commitment to intellectual rigor and her belief in the power of thinking as a bulwark against the forces of totalitarianism, conformity, and the erosion of human dignity shine through. Her insights continue to inspire and challenge scholars, philosophers, and anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the human condition and our collective capacity for moral and ethical reasoning.

Time Line of Arendt’s Life

Early Life and Education

1906: Born on October 14th in Hanover, Germany.

1924: Begins studying at the University of Marburg under Martin Heidegger, with whom she has a brief romantic relationship.

1925-1926: Studies at the University of Freiburg under Edmund Husserl.

1926-1929: Completes her doctoral dissertation under Karl Jaspers at the University of Heidelberg on the concept of love in Saint Augustine’s thought.

Escape from Germany and Academic Career

1933: Flees Nazi Germany first to Czechoslovakia, then Geneva, and finally Paris after the rise of Hitler due to her Jewish heritage and political activism.

1941: Emigrates to the United States with her husband, Heinrich Blücher, after being detained in an internment camp in France as an enemy alien.

1944-1946: Works for the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction.

1951: Becomes a U.S. citizen.

Major Published Works

1951: Publishes “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” analyzing the roots and nature of totalitarian regimes.

1958: Publishes “The Human Condition,” exploring the nature of human activities and the vita activa.

1961: Attends the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem and later publishes articles in “The New Yorker,” which are expanded into “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil” in 1963, introducing the controversial concept of the “banality of evil.”

1963: “On Revolution,” examining the differences between the American and French revolutions.

1968: Becomes the first female lecturer at Princeton University.

1970: Publishes “On Violence,” discussing the nature of power and violence.

1972: “Crises of the Republic,” a collection of essays on American politics, civil disobedience, and the Pentagon Papers.

Later Life and Death

1975: Hannah Arendt dies on December 4th in New York City.

Posthumous Publications

1978: “The Life of the Mind,” her unfinished work on the faculties of thinking, willing, and judging, is published posthumously.

Arendt’s legacy continues to influence political thought, philosophy, and the study of totalitarianism, authority, and democracy. Her work is characterized by a deep concern for the conditions of human existence and the political community.

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/

Bibliography:

Arendt, H. (1951). The Origins of Totalitarianism. Harcourt, Brace. Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition. The University of Chicago Press. Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. The Viking Press. Arendt, H. (1963). On Revolution. The Viking Press. Arendt, H. (1970). On Violence. Harcourt, Brace & World. Arendt, H. (1972). Crises of the Republic. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Arendt, H. (1978). The Life of the Mind. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Further Reading:

Benhabib, S. (2003). The Reluctant Modernism of Hannah Arendt. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Canovan, M. (1992). Hannah Arendt: A Reinterpretation of Her Political Thought. Cambridge University Press. Deutscher, P. (2007). Judgment after Arendt. Ashgate. Kateb, G. (1984). Hannah Arendt: Politics, Conscience, Evil. Rowman & Allanheld. Kohn, J. (2002). Hannah Arendt: Thinking, Judging, Freedom. Allen & Unwin. Villa, D. (1996). Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political. Princeton University Press. Young-Bruehl, E. (1982). Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World. Yale University Press.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Philosophy

0 Comments