Who was Walter Benjamin

Who was Walter Benjamin

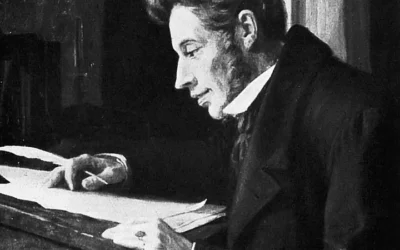

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) was a highly influential German-Jewish philosopher, cultural critic, and essayist whose groundbreaking ideas left a profound impact on 20th century thought and continue to shape intellectual discourse today. Associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory, Benjamin was a pioneering thinker who explored a wide range of subjects including art, literature, history, politics, and technology. His incisive analyses of modernity, mass culture, and aesthetics offered penetrating insights into the social upheavals and transformations of his era.

Life and Career

Benjamin was born into an affluent assimilated Jewish family in Berlin in 1892. He studied philosophy at the University of Freiburg and later at the University of Berlin, where he came under the influence of thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. In 1919, he completed his doctoral dissertation on the concept of art criticism in German Romanticism.

During the 1920s, Benjamin became loosely associated with the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, also known as the Frankfurt School. While never an official member, he maintained close intellectual ties with prominent figures such as Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Gershom Scholem. The Frankfurt School aimed to develop a critical theory of society integrating Marxist analysis with insights from philosophy, sociology, psychoanalysis and other fields. Benjamin’s work, while distinct in style and approach, aligned with the School’s mission of diagnosing and challenging the ideological structures of capitalist modernity.

The rise of Nazism in the 1930s forced Benjamin into exile, first to Ibiza and Nice, and then to Paris. His years in Paris were marked by financial hardship and a precarious existence as a refugee, but also great intellectual ferment. It was here that Benjamin produced much of his mature work, including seminal essays such as “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936) and the unfinished magnum opus The Arcades Project.

Tragically, Benjamin’s life was cut short in 1940 while attempting to flee Nazi persecution. After being denied entry into Spain, he took his own life, fearing capture by the Gestapo and deportation to a concentration camp. Much of his work was unpublished during his lifetime, only reaching a wide audience posthumously thanks to the efforts of admirers like Adorno and Hannah Arendt.

Key Ideas

The Decline of Aura:

In his famous 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin argued that the proliferation of mass reproduction technologies like photography and film had shattered the unique “aura” traditionally associated with art objects. While this loss of authenticity was in some ways democratizing, making art more accessible to the masses, it also opened new possibilities for political manipulation by totalitarian regimes. Benjamin thus highlighted how technology was reshaping human perception and imagination in the modern age, with both liberating and threatening implications.

The Dialectical Image:

Central to Benjamin’s historical method was his concept of the “dialectical image”—a way of illuminating the present by revisiting fragments of the forgotten past. For Benjamin, history was not a triumphal march of progress, but a landscape of ruins and lost possibilities that needed to be “brushed against the grain.” By juxtaposing seeming unrelated images, the critic could reveal hidden connections and jolt the collective consciousness into recognizing the unfulfilled utopian dreams haunting the present. Benjamin’s unfinished Arcades Project epitomized this approach, using the 19th century Parisian shopping arcades as a prism for investigating the myths and antinomies of industrial capitalism.

The Allegorical and the Auratic:

Throughout his literary essays, Benjamin explored the tension between the symbolic and critical power of language. Drawing on the mystical idea of a “pure language” of names, he championed modes of writing that could rupture the reified surfaces of commodity society and gesture towards transcendent meaning. In contrast to the instrumental rationality and positivism dominating both capitalist and orthodox Marxist thought, Benjamin sought to recover the “secret index” by which the past charged the present with messianic import. Allegory, montage, quotation—for Benjamin, these were vital tools for preserving the fleeting traces of an oppressed past and igniting the political imagination.

The Flâneur and Mass Culture:

Many of Benjamin’s city writings centered on the figure of the flâneur—the idle stroller and detached observer of urban life. In texts like One-Way Street and his Baudelaire studies, Benjamin portrayed the flâneur as an ambivalent symbol of modernity, at once attuned to the phantasmagoria of commodity culture and a potential agent of resistance to its anaesthetizing effects. Through the flâneur’s gaze, Benjamin sought to decipher the mythic fantasies and collective wishes inscribed in the ephemera of popular culture, from street signs to world exhibitions. In excavating the utopian residues within the capitalist “dream-worlds” of the 19th century, Benjamin aimed to nourish oppositional impulses in the present.

Messianic Time and Revolutionary Praxis: Benjamin’s understanding of temporality and revolutionary politics found its most concentrated expression in his final work, “On the Concept of History” or “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940). Written on the eve of his death, the fragmentary theses mounted a blistering critique of the ideology of progress shared by bourgeois historicism and vulgar Marxism. Against notions of gradual evolution or automatic deliverance, Benjamin counterposed a “weak messianic power” oriented towards cataclysmic rupture. For a humanity on the brink of catastrophe, genuine historical knowledge meant seizing hold of endangered moments to “blast open the continuum of history.” Revolution thus entailed not a teleological end-goal, but a disruption of the false eternal present to redeem the crushed hopes of the downtrodden.

Legacy and Influence

Though he remained a marginal figure during his lifetime, Benjamin’s thought has posthumously attained immense stature, inspiring thinkers across a spectrum of disciplines from philosophy and political theory to art history, film studies, and literary criticism. His essays on Baudelaire and 19th century Paris became touchstones for scholars interrogating the origins and experience of urban modernity. Figures as diverse as Hannah Arendt, Bertolt Brecht, Georges Bataille, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Giorgio Agamben have acknowledged their debts to Benjamin’s innovative ideas and methods.

In the 1960s, Benjamin was enthusiastically taken up by the student movements in Germany, France, and elsewhere as a kind of patron saint of the revolutionary imagination. His writings on the philosophy of history galvanized New Left thinkers searching for alternatives to the reformist dogmas of the Old Left and the authoritarian repression of Soviet-style communism. The publication of The Arcades Project in the 1980s spurred a surge of academic interest in Benjamin, cementing his reputation as one of the 20th century’s most formidable and original intellects.

Today, Benjamin’s star shines brighter than ever, as new generations grapple with many of the same crises and conundrums he confronted—the tensions between capitalism and democracy, technology and freedom, culture and barbarism. In an era saturated with digital images and “content,” Benjamin’s writings on art, media, and perception have acquired fresh relevance and urgency. Likewise, his fragmentary, montage-like style of writing, once seen as bewildering, now appears strikingly contemporary—a forerunner of “quote-thinking,” hypertext, and remix culture.

Perhaps most importantly, Benjamin’s lifelong struggle to redeem the suffering of history’s forgotten and dispossessed continues to nourish the utopian imagination. For all those who refuse to accept the current state of emergency as inevitable—from anti-capitalist activists to decolonial artists—Benjamin endures as an indispensable thinker and exemplary witness. In shattering the mythic spell of the victors, his work prepares us to recognize the flashing up of unrealized possibilities in our own endangered present. As Benjamin wrote in his final, desperate hours, “In every era the attempt must be made anew to wrest tradition away from a conformism that is about to overpower it.” It is this undiminished faith in the transformative potential of remembrance that remains Benjamin’s greatest legacy and challenge to us today.

Trauma, Fragmentation, and the Dialectical Image

“Memory is not an instrument for surveying the past but its theater. It is the medium of past experience, just as the earth is the medium in which dead cities lie buried. He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging.”

―

One of the key aspects of Benjamin’s thought that holds relevance for psychotherapy is his notion of the dialectical image and his understanding of history as a series of fragmentary, often traumatic, moments. For individuals who have experienced trauma, the past can often feel like a series of disconnected, painful fragments that resist integration into a coherent narrative. Benjamin’s concept of the dialectical image suggests that it is precisely by bringing together these seemingly disparate fragments that we can begin to illuminate the hidden truths and potentialities of the present moment. In the context of therapy, this idea can inform approaches that seek to help individuals make sense of their traumatic experiences and to find meaning and possibility in the midst of fragmentation and pain. By encouraging individuals to engage critically and creatively with the fragments of their past, therapists can help them to develop new understandings of their experiences and to identify potential sources of resilience and healing. Another important aspect of Benjamin’s thought that holds relevance for psychotherapy is his emphasis on the political and collective dimensions of human experience. For Benjamin, the suffering and trauma of individuals cannot be understood in isolation from the broader social, economic, and political forces that shape their lives. This insight challenges therapeutic approaches that focus solely on individual pathology and instead highlights the need to address the structural and systemic factors that contribute to psychological distress.

In the treatment of trauma, this perspective suggests the importance of not only addressing individual symptoms and experiences but also working to transform the social and political conditions that perpetuate violence, oppression, and inequality. Therapists who are informed by Benjamin’s ideas may seek to help individuals not only heal from their own traumatic experiences but also to develop a critical consciousness and a sense of agency in the face of collective struggles. Benjamin’s insights into the transformative potential of art and storytelling offer valuable resources for therapeutic work with trauma survivors. For Benjamin, art held the power to disrupt dominant narratives, to give voice to marginalized experiences, and to create spaces for collective healing and resistance. In the context of therapy, this suggests the importance of incorporating creative and expressive practices into the therapeutic process, such as writing, visual art, or performance. By encouraging individuals to engage in creative storytelling and artistic expression, therapists can help them to make meaning of their experiences, to assert their agency and voice, and to connect with others who share similar struggles. Moreover, by bringing traumatic experiences into the realm of cultural production and public discourse, such practices can contribute to broader processes of social and political transformation.

While Walter Benjamin’s ideas were not developed with psychotherapy or trauma treatment in mind, they nevertheless offer valuable frameworks for understanding the complex interplay between individual suffering and collective struggles. By engaging critically and creatively with Benjamin’s concepts, therapists can develop new approaches to trauma work that address not only individual healing but also the transformation of the social and political conditions that perpetuate violence and oppression. At the same time, Benjamin’s emphasis on the fragmentary and contradictory nature of human experience, as well as his faith in the transformative potential of art and storytelling, offer hope and possibility in the face of even the most profound experiences of trauma and loss. By helping individuals to make meaning of their experiences, to find agency and resilience in the midst of suffering, and to connect with others in the struggle for a more just and equitable world, therapists can play a vital role in realizing the emancipatory potential that lies within even the darkest moments of human history.

“To be happy is to be able to become aware of oneself without fright.”

―

Walter Benjamin’s thought represents a unique and powerful contribution to 20th-century philosophy and cultural criticism. While deeply engaged with the intellectual currents of his time, particularly Marxism and the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, Benjamin’s work transcended the boundaries of any single discipline or ideological framework. His critique of progress, his exploration of the transformative potential of art and technology, and his innovative approach to historical and cultural analysis continue to resonate with contemporary audiences and to offer valuable insights into the challenges and possibilities of the modern world. In a time of rapid social, technological, and political change, Benjamin’s ideas take on renewed relevance and urgency. His warnings about the dangers of mass reproduction and political manipulation, as well as his hopeful vision of the democratizing potential of new technologies, provide essential frameworks for navigating the complexities of our digital age. At the same time, his emphasis on the revolutionary potential of the present moment and his resistance to the illusion of inevitable progress offer a powerful challenge to dominant ideologies and a call to action for those seeking to build a more just and equitable society. As we continue to grapple with the legacy of modernity and the challenges of the contemporary world, Walter Benjamin’s thought remains an essential resource and source of inspiration. By engaging critically and creatively with his ideas, we can develop new ways of seeing and understanding the world around us, and work towards realizing the emancipatory potential that lies within even the most fragmented and contradictory aspects of modern life. In this sense, Benjamin’s work represents not only a profound contribution to the history of ideas, but also a vital resource for imagining and creating alternative futures.

Walter Benjamin’s Life and Work

Timeline of Walter Benjamin’s Life

Walter Benjamin’s Publications:

“The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936):

In this seminal essay, Benjamin explores the impact of mass reproduction on the nature and perception of art. He argues that the advent of film and photography has fundamentally altered the “aura” of the artwork, demystifying its uniqueness and authenticity. Benjamin sees this shift as a potentially democratizing force, enabling the masses to access and engage with art in unprecedented ways. However, he also warns of the potential for mass reproduction to be harnessed by authoritarian regimes for the purposes of propaganda and control. Benjamin’s insights into the relationship between art, technology, and politics continue to resonate in our digital age, inviting us to reflect on the transformative power and potential dangers of new media.

“Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940):

In this fragmentary and enigmatic text, Benjamin offers a radical critique of traditional historiography and the notion of progress. He rejects the idea of history as a linear, continuous narrative leading inevitably towards a better future, instead emphasizing the discontinuities, ruptures, and moments of revolutionary potential that punctuate the historical process. Benjamin’s central image is that of the “angel of history,” propelled into the future by the storm of progress while facing the wreckage of the past. He calls for a new understanding of history that recognizes the suffering of the oppressed and the unrealized possibilities of the vanquished. Benjamin’s “Theses” have become a touchstone for critical theory and alternative conceptions of historical time, inspiring thinkers and activists seeking to imagine a more just and redemptive future.

“The Arcades Project” (1927-1940, published posthumously):

This monumental, unfinished work showcases Benjamin’s distinctive approach to cultural history and criticism. Conceived as a study of the Parisian arcades of the 19th century, the project evolved into a sprawling, labyrinthine exploration of modernity, consumerism, and urban experience. Through a vast collection of quotations, reflections, and fragmentary analyses, Benjamin seeks to construct a “dialectical image” of the arcades as a microcosm of the contradictions and fantasies of modern capitalism. He explores themes such as the commodification of desire, the dream-like quality of the city, and the revolutionary potential hidden within the detritus of mass culture. Although incomplete, “The Arcades Project” stands as a testament to Benjamin’s innovative method and his enduring fascination with the secret affinities and correspondences that structure the modern world.

Timeline of Benjamin’s Life:

Early Life and Education

1892: Born into a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin.

1912: Enters the University of Freiburg to study philosophy, later moving to the University of Berlin.

1919: Completes his doctoral dissertation on the concept of art criticism in German Romanticism.

Intellectual Development and Exile

1920s: Becomes associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory and develops friendships with key figures such as Theodor Adorno and Gershom Scholem.

1933: Flees Nazi Germany for Paris, where he remains in exile for the rest of his life.

1935-1939: Works on “The Arcades Project” while struggling with financial hardship and precarious living conditions.

Final Years and Tragic Death

1940: Attempts to escape Nazi-occupied France by crossing the Spanish border, but is detained by Spanish authorities.

1940: Takes his own life on September 26th, fearing deportation back to Nazi Germany.

Posthumous Recognition and Legacy

1955: “Illuminations,” a collection of Benjamin’s essays translated by Hannah Arendt, introduces his work to an English-speaking audience.

1960s-Present: Growing recognition of Benjamin’s significance as a cultural theorist, philosopher, and literary critic, with his works translated into numerous languages and inspiring scholars across disciplines.

Walter Benjamin’s life and work bear witness to the tumultuous history of the early 20th century and the ongoing struggle to comprehend the complexities of modernity. His innovative approach to cultural criticism, his philosophical acuity, and his commitment to the redemptive potential of historical remembrance make him a vital and enduring presence in contemporary thought.

“At a certain moment, the pain is lessened by projecting it into the universe, but the universe is impaired; the pain is more intense when it comes home again, but something in me does not suffer and remains in contact with a universe which is not impaired.

– Simone Weil”

— Simone Weil (Gravity and Grace)

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/

Bibliography:

Benjamin, W. (2008). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Penguin Books. Benjamin, W. (2019). Illuminations. Penguin Classics. Benjamin, W. (1999). The Arcades Project. Harvard University Press. Benjamin, W. (2019). On the Concept of History. Verso. Benjamin, W. (2019). One-Way Street. Verso. Benjamin, W. (2019). Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings. Schocken.

Further Reading:

Arendt, H. (1968). Walter Benjamin: 1892-1940. Harcourt, Brace & World. Bischof, R. (2017). Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Bloomsbury. Buck-Morss, S. (1989). The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. MIT Press. Caygill, H. (1998). Walter Benjamin: The Colour of Experience. Routledge. Cohen, M. (1993). Profane Illumination: Walter Benjamin and the Paris of Surrealist Revolution. University of California Press. Eiland, H., & Jennings, M. W. (2014). Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life. Harvard University Press. Hanssen, B. (2000). Walter Benjamin’s Other History: Of Stones, Animals, Human Beings, and Angels. University of California Press. Hillach, A. (1981). The Aesthetics of Politics: Walter Benjamin’s “Theories of German Fascism”. New German Critique, (17), 99-119. Hullot-Kentor, R. (2006). Things Beyond Resemblance: Collected Essays on Theodor W. Adorno. Columbia University Press. Jennings, M. W. (1987). Dialectical Images: Walter Benjamin’s Theory of Literary Criticism. Cornell University Press. Leslie, E. (2000). Walter Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism. Pluto Press. McCole, J. (1993). Walter Benjamin and the Antinomies of Tradition. Cornell University Press. Wolin, R. (2006). Walter Benjamin: An Aesthetic of Redemption. University of California Press.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Philosophy

0 Comments