Who are Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker?

In their seminal 2010 essay “Notes on Metamodernism”, cultural theorists Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker outlined an emerging cultural paradigm they dubbed “metamodernism”. Oscillating between the opposing poles of modernist sincerity and postmodern irony, the metamodern sensibility attempts to transcend the aporia of the postmodern era without regressing to the naivete of the modern. This article will explore the implications of Vermeulen and van den Akker’s metamodern theory for the fields of depth psychology and psychotherapy, with a particular focus on the treatment of trauma in the contemporary era. We will examine how metamodernism’s unique understanding of the relationship between subjectivity, spirituality and society resonates with key concepts from Jungian and post-Jungian thought, while also challenging some of the assumptions of classical approaches to trauma therapy. Ultimately, we will argue that a metamodern perspective offers a timely and necessary framework for re-envisioning the therapeutic encounter in the face of the epistemic, existential and ethical uncertainties of the present moment.

The Metamodern Turn

Modernism, Postmodernism and Beyond

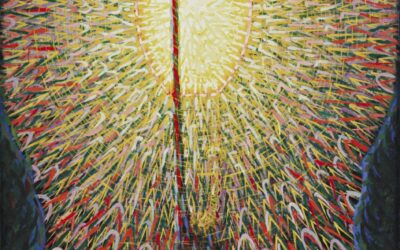

To understand the significance of metamodernism, it is necessary to situate it within the broader context of 20th century cultural history. Modernism, which reached its apex in the early-to-mid 20th century, was characterized by a utopian faith in progress, rationality and universal truths. Rooted in the values of the Enlightenment, modernists sought to transcend the limitations of tradition and construct a new social order based on reason, science and individual liberty. In the realm of art and aesthetics, this manifested as a drive towards purity, abstraction and formal experimentation.

Postmodernism, which emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, represented a radical critique of these modernist assumptions. Postmodernists rejected the idea of objective truth, emphasizing instead the ways in which knowledge is always socially constructed and historically contingent. They deconstructed the grand narratives of modernity, exposing their hidden ideological agendas and inherent contradictions. In the arts, this took the form of pastiche, irony and a blurring of high and low cultural boundaries.

Vermeulen and van den Akker argue that both of these paradigms have reached a point of exhaustion. The utopian energies of modernism have dissipated in the face of historical catastrophes and failed revolutions, while the critical project of postmodernism has devolved into a cynical relativism that offers little in the way of constructive vision. What is needed, they suggest, is a new cultural logic that synthesizes the insights of both while moving beyond their limitations. This is the promise of metamodernism.

Metamodern Oscillation and the “Structure of Feeling”

At the heart of Vermeulen and van den Akker’s theory is the concept of “oscillation“. Metamodernism, they argue, is characterized by a constant shifting between seemingly incompatible polarities: sincerity and irony, hope and melancholy, naivete and knowingness, construction and deconstruction. Rather than attempting to resolve these tensions through dialectical synthesis, the metamodern sensibility allows them to coexist in a state of productive ambivalence.

This oscillatory dynamic reflects what Vermeulen and van den Akker, borrowing a term from Raymond Williams, call a new “structure of feeling” – an emergent pattern of lived experience that is not yet fully articulated but can be discerned in various cultural artifacts and practices. Metamodern works of art and literature, for instance, often exhibit a strange mix of earnestness and self-reflexivity, combining a yearning for meaning and depth with an acute awareness of the problems of representation.

Implications for Depth Psychology

The Jungian Roots of Metamodernism

While Vermeulen and van den Akker do not explicitly engage with depth psychological concepts, their theory has striking resonances with key ideas from the Jungian tradition. Jung’s notion of the “transcendent function”, for instance, bears a remarkable similarity to metamodern oscillation. For Jung, psychological growth occurs through the creative tension between conscious and unconscious forces, a dynamic that cannot be resolved but must be continually negotiated. This is the essence of the individuation process – the lifelong project of integrating the various aspects of the psyche into a more complete and authentic selfhood.

Similarly, Jung’s understanding of the role of spirituality in psychological development prefigures the metamodern attempt to recover a sense of depth and meaning in a postmodern context. Jung saw the religious impulse as an innate human drive, a natural expression of the psyche’s striving for wholeness. Yet he also recognized that traditional religious forms were losing their hold in the modern era, necessitating the development of new modes of spirituality. This is precisely the challenge that metamodernism takes up – how to cultivate experiences of transcendence and enchantment in a world that has been thoroughly disenchanted by the critical acids of postmodernity.

The Politics of the Psyche

Vermeulen and van den Akker’s theory also has important implications for understanding the political dimensions of psychological life. They argue that metamodernism represents a new form of political engagement, one that eschews both the grand ideological projects of modernism and the ironic detachment of postmodernism. Metamodern politics is characterized by a pragmatic idealism, a commitment to making incremental progress within the constraints of a complex and uncertain reality.

From a depth psychological perspective, this suggests a new way of thinking about the relationship between the individual and the collective. Classical Jungian theory tended to prioritize the inner world of the psyche over the outer world of society, seeing political activism as a potential distraction from the real work of individuation. But a metamodern approach recognizes that the two are inextricably intertwined – that our personal struggles and transformations are always embedded in larger cultural and historical contexts.

This is particularly relevant for understanding the politics of trauma in the contemporary era. As theorists like Judith Herman have argued, trauma is not just an individual psychological phenomenon but a social and political one as well. The experience of trauma is shaped by the power dynamics of race, class, gender and other forms of structural oppression. And the healing of trauma requires not just individual therapy but collective action to challenge and transform these oppressive systems.

A metamodern approach to trauma therapy, then, would recognize the need to work on both the micro and macro levels – to address the immediate psychological needs of the individual while also engaging in broader efforts to create a more just and equitable society. It would seek to cultivate a sense of agency and empowerment in the face of overwhelming experiences of powerlessness, while also acknowledging the limits of individual control in a complex and interdependent world.

Implications for Trauma Therapy

Beyond the Postmodern Impasse

The field of trauma studies emerged in the late 20th century as a response to the failures of classical psychoanalytic theory to adequately account for the impact of overwhelming experiences on the psyche. Pioneers like Judith Herman, Bessel van der Kolk and Francine Shapiro developed new models of trauma that emphasized the centrality of the body, the importance of safety and the need for a phased approach to treatment.

Yet in many ways, these models still operated within a largely modernist framework. They sought to establish a scientific basis for trauma treatment, grounded in empirical research and standardized protocols. And they tended to focus on the individual psyche as the primary site of intervention, often at the expense of a more systemic understanding of trauma.

The postmodern turn in trauma studies, exemplified by thinkers like Cathy Caruth and Shoshana Felman, challenged these assumptions. Drawing on deconstructionist and psychoanalytic theory, they emphasized the ways in which trauma resists representation and narrativization. They argued that trauma is not just an individual pathology but a crisis of meaning that implicates the very foundations of language and subjectivity.

While these insights were crucial for deepening our understanding of trauma, they also tended to lead to a kind of therapeutic impasse. If trauma is inherently unspeakable and unrepresentable, then how can it be worked through in therapy? If the very notion of coherent selfhood is called into question by traumatic experience, then what is the goal of treatment?

Metamodernism offers a way out of this impasse by reframing the relationship between language and experience. Vermeulen and van den Akker argue that metamodernism represents a renewed faith in the power of storytelling and myth-making, not as a means of representing reality but of constructing new realities. They see the metamodern artist as a “mythopoetic bricoleur” who cobbles together fragments of meaning to create new narratives of identity and belonging.

Applied to the therapeutic context, this suggests a new approach to trauma treatment that emphasizes the co-creation of meaning between therapist and client. Rather than striving for a definitive account of what happened, the goal is to construct a narrative that allows the client to make sense of their experience and integrate it into a coherent sense of self. This is not a matter of imposing a pre-existing template but of engaging in a collaborative process of exploration and experimentation.

Embodiment, Enactment and the Posttraumatic Self

Another key aspect of metamodern trauma therapy is a focus on embodiment and enactment. As theorists like Bessel van der Kolk have long argued, trauma is not just a psychological phenomenon but a physiological one as well. It is encoded in the body’s nervous system, in patterns of tension and constriction that often persist long after the original event.

Metamodern therapy seeks to work with these bodily experiences rather than just talking about them. This might involve techniques like somatic experiencing, sensorimotor psychotherapy or body-oriented meditation practices. The goal is to help clients develop a new relationship with their bodies, one that is characterized by greater awareness, flexibility and self-regulation.

But embodiment is not just about individual physiology. It is also about the ways in which we enact our identities and relationships in the world. A metamodern approach recognizes that the self is not a static entity but an ongoing process of becoming that is shaped by our interactions with others and our environment.

This is particularly relevant for understanding the impact of trauma on identity. Traumatic experiences often shatter our assumptions about ourselves and the world, leaving us feeling fragmented and disconnected. The task of therapy, then, is not just to restore a pre-existing sense of self but to support the emergence of a new, posttraumatic identity.

This involves a process of experimentation and play, of trying on different roles and ways of being in the world. It means embracing the fluidity and multiplicity of the self, rather than striving for a fixed and unified identity. And it requires a willingness to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty, to dwell in the liminal space between who we have been and who we are becoming.

The Ecology of Trauma

Finally, a metamodern approach to trauma therapy recognizes that healing is not just an individual process but a collective one. Trauma is not just a psychological event but a social and cultural one as well. It is shaped by the larger systems and structures in which we live, from families and communities to institutions and ideologies.

This means that trauma treatment must address not just the individual psyche but the broader ecology of relationships and contexts in which it is embedded. It requires a systemic understanding of how trauma is produced and perpetuated, and a commitment to transforming the conditions that give rise to it.

This might involve working with families and communities to build resilience and support networks. It might mean advocating for policy changes and institutional reforms to address the root causes of trauma. And it might entail engaging in broader cultural and political struggles to create a more just and equitable society.

At the same time, a metamodern approach recognizes that these systemic interventions are not separate from the work of individual therapy but deeply interconnected with it. The healing of the individual psyche is always bound up with the healing of the larger social body. And the transformation of society requires the transformation of the individuals who compose it.

Implications of the meta modern for therapy

Metamodernism offers a powerful framework for re-envisioning the theory and practice of trauma therapy in the 21st century. By integrating the insights of depth psychology with a nuanced understanding of contemporary culture and politics, it points the way towards a more holistic and contextual approach to healing.

This approach recognizes the irreducible complexity of traumatic experience, the ways in which it implicates both individual and collective dimensions of life. It seeks to work with the embodied, enacted and relational aspects of the self, rather than just the cognitive and linguistic ones. And it situates the therapeutic encounter within a larger ecology of meaning and power.

Of course, as Vermeulen and van den Akker are quick to point out, metamodernism is not a panacea or a fully realized paradigm but an emergent sensibility, a tentative and provisional attempt to articulate a new way of being in the world. It is a work in progress, an invitation to ongoing dialogue and experimentation.

But for those of us engaged in the work of healing trauma, it offers a much-needed sense of hope and possibility. It reminds us that even in the face of overwhelming suffering and injustice, we have the capacity to create new meanings, new identities and new forms of life. And it calls us to embrace the paradox at the heart of the therapeutic encounter – that in the very act of facing our brokenness, we may discover a deeper wholeness.

References

Vermeulen, T., & van den Akker, R. (2010). Notes on metamodernism. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 2(1), 5677.

Jung, C. G. (1958). The transcendent function. Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 8. Princeton University Press.

Herman, J. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence – from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Caruth, C. (1996). Unclaimed experience: Trauma, narrative, and history. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Felman, S., & Laub, D. (1992). Testimony: Crises of witnessing in literature, psychoanalysis, and history. Routledge.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2009). Immunity to change: How to overcome it and unlock potential in yourself and your organization. Harvard Business Press.

Habermas, J. (1981). Modernity versus postmodernity. New German Critique, (22), 3-14.

Metamodernism and Post Secularism

0 Comments