-

Who was Wilfred Bion?

Wilfred Bion (1897-1979) was a highly influential British psychoanalyst known for his groundbreaking contributions to the understanding of thinking, groups, and psychosis. His dense, evocative theoretical works, often conveyed through poetic and paradoxical language, have had a profound impact on contemporary psychoanalytic theory and technique. Bion’s innovative ideas about the nature of thoughts, the intersubjective field of analysis, and the importance of dreaming for mental life continue to inspire clinicians, scholars, and artists across many disciplines.

-

Biographical Background

Wilfred Ruprecht Bion was born in 1897 in Mathura, India, where his father worked as a civil engineer. He had a difficult childhood marked by the early loss of his mother and a strained relationship with his emotionally distant father. At the age of eight, Bion was sent to boarding school in England, an experience he later described as a profound rupture.

After finishing school, Bion joined the Royal Tank Regiment and served in World War I. His harrowing experiences in the trenches, including being left for dead on the battlefield, left an indelible mark on his psyche and profoundly shaped his later thinking about groups, leadership, and the primitive anxieties that underlie social life.

Following the war, Bion studied history at Queen’s College, Oxford and then pursued medical training at University College London. It was during his time as a medical student that he began a training analysis with John Rickman, one of the pioneers of group analysis. This experience sparked Bion’s lifelong fascination with psychoanalysis.

In the 1930s, Bion worked as a psychiatrist at the Tavistock Clinic in London, where he began to develop his innovative ideas about groups. During World War II, he was a key figure in the Northfield Experiments, a pioneering effort to apply psychoanalytic principles to the treatment of soldiers suffering from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder.

After the war, Bion underwent further psychoanalytic training with Melanie Klein, whose ideas about primitive mental states and the early mother-infant relationship deeply influenced his thinking. He also had a brief analysis with Paula Heimann. Bion went on to become a leading figure in the British Psychoanalytical Society, known for his creative extensions of Kleinian theory.

Timeline of Bion’s Life

1897: Born in Mathura, India

1905: Sent to boarding school in England

1916: Serves in World War I; experiences severe trauma

1919: Begins studying history at Queen’s College, Oxford

1924: Starts medical training at University College London

1930s: Works at the Tavistock Clinic; begins developing ideas about groups

1940s: Serves as a psychiatrist in the British Army during World War II; participates in the Northfield Experiments

1950s: Undergoes psychoanalytic training with Melanie Klein and others; becomes a leading figure in the British Psychoanalytical Society

1960s: Publishes influential works such as “Experiences in Groups,” “Learning from Experience,” and “Elements of Psycho-Analysis”

1970s: Publishes the trilogy “A Memoir of the Future”; continues to develop his ideas about thinking, dreaming, and the analytic relationship

1979: Dies in Oxford, England

-

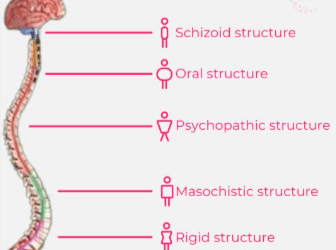

Theory of Thinking and “Alpha Function”

At the heart of Bion’s theoretical edifice is his unique conception of thinking and its origins. In his seminal work “Learning from Experience” (1962), Bion proposed that thoughts are not the product of a thinking apparatus, but rather precede the development of such an apparatus. For Bion, the infant is born into a world of raw sensory impressions and unprocessed emotional experiences, which he termed “beta elements.” These beta elements are felt to be things-in-themselves, indistinguishable from the infant’s own being.

To make sense of this chaotic experiential world, the infant needs the help of a maternal figure who can receive, contain, and transform these beta elements into meaningful mental contents, which Bion called “alpha elements.” This process of transformation is achieved through the mother’s “alpha function,” her capacity for reverie and meaning-making.

When the mother is able to bear the infant’s projective identifications and metabolize them through her alpha function, she returns them to the infant in a more manageable, thinkable form. The infant can then reinternalize these alpha elements and use them to build a thinking apparatus, a “contact-barrier” that can distinguish between conscious and unconscious, self and other, phantasy and reality.

However, if the mother is unable to provide adequate containment and alpha function, the infant is left overwhelmed by unprocessed beta elements. This state of “beta flooding” is characterized by a terror of annihilation and a desperate resort to primitive defenses such as splitting, projection, and denial. For Bion, this catastrophic failure of the contact-barrier is at the root of psychosis.

Bion’s theory of thinking thus places the intersubjective relationship between container and contained at the center of mental life. It highlights the vital importance of a receptive, transformative maternal presence for the development of a capacity for thought, symbolization, and emotional processing.

-

Bion’s Engagement with Dreams

Dreams played a central role in Bion’s understanding of the analytic process and the growth of the mind. Drawing on his concept of alpha function, Bion saw dreaming as essential for the processing of emotional experience and the expansion of our capacity for thinking.

In contrast to Freud’s emphasis on the disguised wish-fulfillments of dreams, Bion viewed dreams as a form of “unconscious waking thinking” that continues the work of alpha function during sleep. Through the dream-work-alpha, undigested beta elements are transformed into thinkable, memorable dream thoughts that can be used for learning and psychic growth.

Bion extended this model of dreaming to the analytic session itself, which he saw as a “waking dream” co-created by analyst and patient. In the intersubjective field of analysis, the patient’s unprocessed beta elements are projected into the analyst, who must use their own alpha function to “dream” the session on the patient’s behalf.

The analyst’s reverie – the freely-floating attentional state that Bion called “negative capability” – is crucial to this process. By remaining open to the patient’s projective identifications and resisting the temptation to understand too quickly, the analyst can receive and transform the patient’s unthinkable thoughts and help them develop a more robust contact barrier.

In psychotic states, however, this vital capacity for dreaming is attacked and dismantled. The patient is unable to think or dream, and is instead haunted by bizarre, concretized “thoughts without a thinker.” The analyst must then work to restore the patient’s alpha function and capacity for symbolic thinking, using their own reverie as a containing, detoxifying presence.

Bion’s understanding of dreaming as central to growth and his emphasis on the analytic relationship as a “waking dream” have had a profound impact on contemporary psychoanalytic technique. His ideas have expanded the field’s understanding of primitive mental states, the origins of thought, and the vital role of the analyst’s receptivity in the therapeutic process.

-

Bion and Science Fiction

Throughout his life, Bion was an avid reader of science fiction, a genre he saw as uniquely suited to exploring the farther reaches of psychic reality. He was particularly drawn to the works of Olaf Stapledon, a British philosopher and science fiction writer known for his visionary epics of cosmic evolution.

For Bion, science fiction provided a “medium of experience” that could capture the ineffable, unthinkable dimensions of the unconscious mind. He used science fictional tropes and narratives as a way of conveying psychoanalytic ideas that strained the limits of ordinary language and linear thought.

This fascination with science fiction found its most direct expression in Bion’s autobiographical work “The Long Week-End” (1982), which interwove his memories of serving in World War I with science fictional elements. In this enigmatic text, Bion used the metaphor of a journey to a distant planet to represent the psychic impact of his traumatic war experiences and the surreal, fragmented nature of traumatic memory.

Bion’s magnum opus, the three-volume “A Memoir of the Future” (1975-1979), pushed this science fictional mode to its limit. A dizzying, labyrinthine work, the Memoir blends psychoanalytic theory, mythology, and science fiction to create a dreamlike space in which Bion could explore the “imaginary twin” of his own unconscious mind.

In the Memoir, Bion used science fictional devices such as time travel, alternate universes, and alien encounters to represent psychotic levels of experience and the breakdown of the contact barrier. He populated this strange, hallucinatory landscape with characters drawn from his own life, the history of psychoanalysis, and mythology, creating a kind of “psychoanalytic science fiction” that sought to evoke the unthinkable origins of thought itself.

While the Memoir remains Bion’s most controversial and perplexing work, it testifies to his lifelong attempt to find a language adequate to the deep structures and transformations of the psyche. By interweaving psychoanalysis with mythical and science-fictional modes of thought, Bion forged visionary tools for apprehending the “unthought known” – the unconscious dimensions of experience that shape our inner world.

Bion’s “A Memoir of the Future” is a complex, multi-layered work that defies easy categorization. Part autobiography, part theoretical treatise, part science fiction novel, the trilogy represents Bion’s most sustained attempt to push the boundaries of psychoanalytic writing and thinking.

In the Memoir, Bion weaves together personal memories, clinical vignettes, mythological allusions, and speculative dialogues, creating a dreamlike narrative that explores the deepest reaches of the psyche. Central to the work is the idea of the “imaginary twin” – a figure representing the unborn potential of the self, the “future personality” that exists in embryonic form within the unconscious.

Through his engagement with this “imaginary twin,” Bion seeks to evoke the process of psychic transformation and growth. He suggests that it is only by confronting and integrating the unknown, unthought dimensions of the self that true psychic change can occur.

At the same time, the Memoir is also a profound meditation on the nature of time, memory, and identity. By interweaving past, present, and future, Bion challenges linear notions of temporal progression, suggesting instead a model of psychic temporality in which all times coexist and interpenetrate.

The science fictional elements of the Memoir – which include dystopian future societies, alien encounters, and cosmic cataclysms – can be understood as metaphors for psychic catastrophe and transformation. They represent Bion’s attempt to give form to the unthinkable, to the catastrophic anxieties that underlie psychotic states of mind.

In this sense, the Memoir can be read as an extended exploration of the breakdown and rebuilding of the self. It is a work that pushes the reader to the very limits of meaning and coherence, enacting the kind of psychic fragmentation and reintegration that it seeks to describe.

The Memoir’s impact on psychoanalytic thought has been profound, if sometimes difficult to pin down. It has inspired countless creative engagements, from clinical papers to artistic works, and has helped to open up new possibilities for psychoanalytic writing and theorizing.

Perhaps most significantly, the Memoir has contributed to a broader reconceptualization of the unconscious as a realm of infinite potential and creativity. By presenting the unconscious as the source of both our deepest terrors and our highest aspirations, Bion invites us to a more open, exploratory, and transformative engagement with the inner world.

At the same time, the Memoir’s highly abstract and unconventional style has sometimes proved challenging for readers seeking clear theoretical or clinical guidance. Its impact has perhaps been more in the realm of inspiring a certain sensibility or attitude – a greater tolerance for uncertainty, paradox, and the unknown in psychoanalytic thinking.

Ultimately, “A Memoir of the Future” stands as a testament to Bion’s unwavering commitment to the truth of psychic reality in all its complexity and mystery. It is a work that challenges us to think beyond the bounds of the familiar, to venture into the uncharted territories of the mind, and to embrace the transformative potential of the unconscious.

In this sense, the Memoir is not just a singular literary achievement, but a call to ongoing psychoanalytic exploration and discovery. It invites us to continue the work that Bion began – to keep pushing at the boundaries of the thinkable, and to remain ever-open to the unexpected emergences of the psyche.

-

Clinical Implications

Bion’s pioneering ideas have had far-reaching implications for psychoanalytic theory and practice. His model of container/contained and his emphasis on the analyst’s receptivity have deeply influenced contemporary understandings of the intersubjective field and the mutative action of the analytic relationship.

Bion’s concept of reverie as a form of “dreaming the session” has become central to many analysts’ clinical sensibility. By attending to their own free-floating internal states and using them as a “receptive organ” for the patient’s projected beta elements, analysts can offer a containing, transformative presence that fosters the growth of the patient’s mind.

This receptivity requires what Bion called “negative capability” – the capacity to tolerate uncertainty, confusion, and emotional turbulence without rushing to premature conclusions or interpretations. By cultivating this state of mind, analysts can help patients to bear the unbearable and to symbolize traumatic beta elements that have been excluded from the contact barrier.

Bion’s ideas have been particularly influential in the treatment of severe psychopathology, including psychosis and borderline states. His understanding of how primitive anxieties can lead to a catastrophic breakdown of the thinking apparatus has illuminated the internal world of psychotic patients and expanded the scope of psychoanalytic treatment.

At the same time, Bion’s dense, often obscure writing style and his unconventional use of literary and scientific sources have sometimes proved challenging for clinicians seeking to apply his ideas. Many analysts have grappled with how to translate Bion’s highly abstract, poetic concepts into the concrete realities of the consulting room.

Despite these challenges, Bion’s clinical legacy endures. His vision of the analytic relationship as a space for dreaming, his respect for the unknowable otherness of the patient, and his deep faith in the growth-promoting power of the unconscious continue to inspire and guide practitioners across the spectrum of psychoanalytic schools and traditions.

-

Legacy and Relevance

Since his death in 1979, Bion’s influence has only continued to grow. His ideas have been taken up and elaborated by generations of analysts, and have found fruitful applications far beyond the clinical domain.

In the field of organizational psychology, Bion’s groundbreaking work with groups has provided a foundation for understanding the irrational, unconscious dynamics that shape institutional life. His concepts of “basic assumptions” and “work group mentality” have become essential tools for consultants, coaches, and leaders seeking to navigate the emotional turbulence of group processes.

Bion’s ideas have also been productively integrated with findings from neuroscience, infant research, and attachment theory. His model of the container/contained relationship has been supported by studies of early mother-infant interactions and the development of affect regulation. Similarly, his understanding of dreaming as central to emotional processing and memory consolidation aligns with contemporary research on REM sleep and the cognitive functions of dreaming.

In the humanities, Bion’s unique fusion of psychoanalysis, literature, and philosophy has inspired a wide range of creative engagements. Scholars in fields ranging from classics to film studies have drawn on his ideas to illuminate the unconscious dimensions of cultural phenomena. And many writers and artists have found in Bion’s work a rich resource for exploring the paradoxes and mysteries of the creative process itself.

This enduring fascination with Bion’s ideas is a testament to their depth, originality, and generative power. By pushing psychoanalysis to its speculative limits, Bion opened up new vistas for the understanding of mental life and its vicissitudes. His lifelong effort to think the unthought and to dream the undreamt continues to enrich and challenge us, inviting us to venture into the uncharted territories of the mind.

Wilfred Bion was one of the most creative and enigmatic thinkers in the history of psychoanalysis. His revolutionary ideas about the nature of thoughts, the intersubjective origins of the mind, and the primacy of emotional experience have left an indelible mark on contemporary psychoanalytic theory and practice.

Through his engagement with dreams and science fiction, Bion sought to extend the reach of psychoanalytic understanding to the farthest horizons of psychic reality. He saw in these imaginative modes a way of capturing the ineffable, paradoxical nature of unconscious experience and the unthinkable origins of thought itself.

At the heart of Bion’s vision was a deep respect for the otherness of the patient and the mystery of the unconscious. He believed that the task of analysis was not to impose meaning on the patient’s experience, but to create a space in which the patient could discover their own truth. This required a radical openness and receptivity on the part of the analyst, a willingness to “dream” the session and to tolerate the uncertainty and confusion of the analytic encounter.

Bion’s ideas have had a profound impact on the way analysts think about their work and their role in the therapeutic process. His emphasis on reverie, negative capability, and the container/contained relationship has deepened our understanding of the intersubjective field and the mutative power of the analytic relationship.

At the same time, Bion’s work continues to challenge and perplex us. His dense, poetic writing style and his unconventional use of literary and scientific sources demand a sustained engagement and a willingness to grapple with complexity and ambiguity. But for those who take up this challenge, Bion’s ideas offer a rich and endlessly generative resource for exploring the depths of the human psyche.

As we navigate the challenges and uncertainties of our own time, Bion’s legacy continues to inspire and guide us. His unwavering commitment to the truth of emotional experience, his faith in the transformative power of the unconscious, and his visionary pursuit of the unthought known remain a beacon for all those who seek to illuminate the mysteries of the mind. In a world that often seems fragmented and adrift, Bion’s work invites us to dream, to think, and to hope.

-

Bion’s Key Works and Their Impact

“Experiences in Groups” (1961): In this seminal work, Bion laid out his theory of group dynamics, introducing concepts such as “basic assumptions” and “work group mentality.” The book has had a profound influence on the fields of group therapy and organizational psychology.

“Learning from Experience” (1962): Here, Bion first articulated his ideas about alpha function, beta elements, and the container/contained relationship. This work established Bion as a major innovative thinker within the British Object Relations school.

“Elements of Psycho-Analysis” (1963): In this dense and complex work, Bion further elaborated his theories of thinking, introducing concepts such as the “grid” and the “selected fact.” The book showcases Bion’s highly abstract and symbolic style of theorizing.

“Transformations” (1965): This book represents Bion’s attempt to create a formal mathematical language for psychoanalysis, drawing on ideas from group theory and projective geometry. While highly controversial, the work testifies to Bion’s ambitious vision of psychoanalysis as a rigorous scientific discipline.

“Attention and Interpretation” (1970): In this work, Bion explored the analyst’s capacity for “negative capability” and the role of intuition in the analytic process. The book had a significant impact on discussions of the analyst’s receptivity and the clinical importance of reverie.

“A Memoir of the Future” (1975-1979): Bion’s enigmatic trilogy, blending autobiography, theoretical speculation, and science fiction. Discussed in more detail below.

Metamodernism and Post Secularism

Navigating the Future of Meta Modern Therapy

Bibliography:

Bion, W. R. (1961). Experiences in Groups and Other Papers. London: Tavistock Publications.

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from Experience. London: Heinemann.

Bion, W. R. (1963). Elements of Psycho-Analysis. London: Heinemann.

Bion, W. R. (1965). Transformations: Change from Learning to Growth. London: Heinemann.

Bion, W. R. (1967). Second Thoughts: Selected Papers on Psychoanalysis. London: Heinemann.

Bion, W. R. (1970). Attention and Interpretation. London: Tavistock Publications.

Bion, W. R. (1975). A Memoir of the Future, Book 1: The Dream. Rio de Janeiro: Imago Editora.

Bion, W. R. (1977). A Memoir of the Future, Book 2: The Past Presented. Rio de Janeiro: Imago Editora.

Bion, W. R. (1979). A Memoir of the Future, Book 3: The Dawn of Oblivion. Rio de Janeiro: Imago Editora.

Bion, W. R. (1982). The Long Week-End, 1897-1919: Part of a Life. Abingdon: Fleetwood Press.

Bleandonu, G. (1994). Wilfred Bion: His Life and Works 1897–1979. London: Free Association Books.

Britton, R. (1998). Belief and Imagination: Explorations in Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge.

Eigen, M. (1998). The Psychoanalytic Mystic. London: Free Association Books.

Ferro, A. (2005). Seeds of Illness, Seeds of Recovery: The Genesis of Suffering and the Role of Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge.

Ferro, A. (2009). Transformations in Dreaming and Characters in the Psychoanalytic Field. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 90(2), 209-230.

Grotstein, J. S. (2007). A Beam of Intense Darkness: Wilfred Bion’s Legacy to Psychoanalysis. London: Karnac Books.

Lopez-Corvo, R. E. (2003). The Dictionary of the Work of W.R. Bion. London: Karnac Books.

Mawson, C. (Ed.). (2011). Bion Today. London: Routledge.

Ogden, T. H. (2004). An Introduction to the Reading of Bion. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 85(2), 285-300.

Schneider, J. A. (2010). From Freud’s Dream-Work to Bion’s Work of Dreaming: The Changing Conception of Dreaming in Psychoanalytic Theory. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 91(3), 521-540.

Symington, J., & Symington, N. (1996). The Clinical Thinking of Wilfred Bion. London: Routledge.

Tustin, F. (1981). Autistic States in Children. London: Routledge.

White, L. (2006). Bion’s Transformation in O. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 87(5), 1193-1210.

0 Comments