Who was Friedrich Hölderlin?

The Course of Life (Lebenslauf)

You too wanted more, but love

Forces all of us under.

Pain’s necessary curve

Returns us to our beginnings.

Whether up or down, in the holiness of night,

Speechless nature determines all the days to come;

Yet in the labyrinths of death

You can find a straight path.

I know this—not once, like mortal instructors

Did you heavenly, all-knowing gods

Have the foresight to lead me

Along a level path.

Everything’s a test, say the gods.

Having found his strength, a man gives thanks

For everything he knows, and, knowing

His freedom, goes where he wants to go.

-Friedrich Hölderlin

Key points and Ideas

Some key themes and ideas in Hölderlin’s work that influenced Jung and other mystics:

- The idea of the gods as personifications of numinous archetypal forces

- The sense of the soul’s exile and homelessness in the modern world

- The longing for reunion with the divine and the sacred dimensions of existence

- The importance of myth, symbol, and poetic language for engaging the depths of the psyche

- The vision of the poet as a mediator between the human and divine realms

- The understanding of madness as a potential shamanic initiation into the underworld of the soul

- The prophetic awareness of the spiritual crisis of modernity and the need for a new mythos

- The affirmation of imagination as a faculty of perception that can apprehend the numinous

- The emphasis on the task of individuation as a mystical journey of transformation

- The tragic sensibility and the embrace of suffering as part of the soul’s destiny

Some key figures influenced by Hölderlin:

- Carl Jung

- Rainer Maria Rilke

- Martin Heidegger

- James Hillman

- Ludwig Binswanger

- Wolfgang Giegerich

- Rudolf Otto

- Walter Benjamin

- Peter Kingsley

- Robert Bly

The Life and Influence of Friedrich Hölderlin

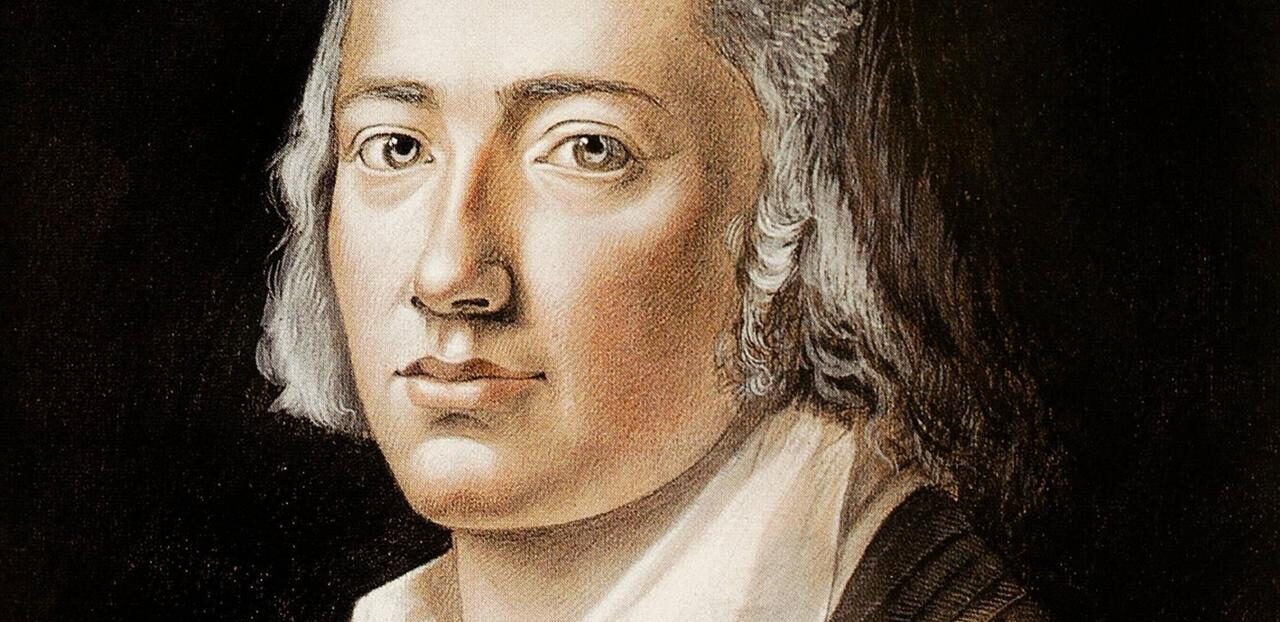

Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843) was a seminal German poet and philosopher whose visionary works had a profound influence on the development of depth psychology, particularly the analytical psychology of Carl Jung. Hölderlin’s poetry and philosophical fragments, though little recognized in his own lifetime, came to be seen as prophetic expressions of the modern soul’s spiritual longings and existential struggles. His insights into the nature of the psyche, the gods, and the relationship between the human and the divine anticipated many of the central themes of Jungian psychology and modern mysticism.

Hölderlin’s work is characterized by a deep attunement to the numinous dimensions of existence – the sacred energies that animate nature, history, and the depths of the soul. Like the Romantics, he saw the imagination as a faculty of perception that could apprehend the living presence of the gods within the world. But unlike the Romantics, Hölderlin’s vision was shaped by a tragic awareness of the soul’s exile in a disenchanted, fragmented modern world. His poetry gives voice to the pain of separation from the divine, the longing for wholeness, and the struggle to create meaning in an age of spiritual crisis.

Jung was deeply influenced by Hölderlin’s perspective and often cited him as a kindred spirit. He saw in Hölderlin’s poetry an intuitive grasp of the archetypal forces that shape the psyche and a prophetic vision of the task of individuation. Like Hölderlin, Jung understood the gods as personifications of the numinous powers that structure the collective unconscious. He believed that the modern psyche suffers from a loss of contact with these powers, leading to spiritual alienation, neurosis, and a sense of meaninglessness.

For Jung, the path to healing and wholeness lies in reconnecting with the archetypal realm – in engaging the gods through myth, symbol, and active imagination. This process of individuation, of forging a conscious relationship to the Self, is ultimately a mystical journey – a descent into the underworld of the psyche to retrieve the lost soul. Hölderlin’s poetry, with its shamanic journeys into the depths and its visionary encounters with the gods, provided Jung with a model for this process.

Hölderlin’s influence can also be seen in the work of other modern mystics and visionary thinkers. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke, for example, drew heavily on Hölderlin’s ideas about the relationship between the human and the divine. Rilke’s Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus echo Hölderlin’s sense of the soul’s homelessness in the modern world and its longing for reunion with the sacred. Like Hölderlin, Rilke saw the poet as a mediator between the human and the divine, a vessel for the numinous energies that seek expression through language.

The philosopher Martin Heidegger also acknowledged Hölderlin as a major influence on his thought. Heidegger saw in Hölderlin’s poetry a revelatory expression of the meaning of Being, the ontological ground of existence. For Heidegger, Hölderlin was a “poet of poets” whose work disclosed the fundamental structures of human existence and pointed the way to a new, post-metaphysical understanding of truth. Heidegger’s concept of “dwelling” as an authentic mode of being-in-the-world owes much to Hölderlin’s vision of the poet as one who inhabits the “between” – the liminal space between gods and mortals, earth and sky.

In the field of archetypal psychology, James Hillman acknowledged Hölderlin as a major precursor to his own approach. Hillman’s emphasis on the reality of the psyche, the importance of imagination, and the need to engage the gods through myth and poetic language all reflect Hölderlin’s influence. Hillman saw in Hölderlin’s madness not a pathology but a shamanic initiation – a radical opening to the depths of the soul and the numinous powers that reside there.

Hölderlin’s legacy also extends to the contemporary world of depth psychology and spirituality. His insights into the nature of the psyche, the importance of myth and symbol, and the need for a new relationship to the sacred continue to inspire thinkers and practitioners working at the intersection of psychology and spirituality. In a world still grappling with the disenchantment and fragmentation of modernity, Hölderlin’s visionary poetry offers a pathway to reconnection and wholeness.

Ultimately, Hölderlin’s significance lies in his prophetic articulation of the soul’s journey in a time of spiritual crisis. His poetry gives voice to the anguish of separation from the divine, the longing for meaning and purpose, and the struggle to create a new mythos for an age of transition. By embracing the tragedy of the modern condition, while also affirming the possibility of transformation and renewal, Hölderlin offers a model of the poetic imagination as a vehicle for spiritual awakening and cultural regeneration.

As we grapple with the challenges of our own time – ecological devastation, social upheaval, existential uncertainty – Hölderlin’s vision takes on new relevance and urgency. His call to engage the depths of the psyche, to reconnect with the numinous dimensions of existence, and to forge a new relationship to the sacred speaks to the deepest longings of the contemporary soul. In our own quest for meaning and wholeness, we can find in Hölderlin a companion and guide – a shamanic poet who points the way to a new mode of being and belonging in a world that is crying out for transformation.

Hölderlin’s visionary poetry and thought played a seminal role in shaping the imaginative and intellectual landscape of modern depth psychology and mysticism. His insights continue to resonate with all those who are striving to forge a new relationship to the sacred in an age of disenchantment and transition. As a prophet of the soul’s journey, Hölderlin remains a vital and inspiring presence for all those seeking meaning, wholeness, and transformation in our time.

2. The Influence of Hölderlin’s Ideas on Jung and Other Mystics

2.1. The Gods as Personifications of Numinous Archetypal Forces

Hölderlin’s conception of the gods as personifications of numinous archetypal forces had a profound influence on Jung’s understanding of the psyche. In his poetry, Hölderlin presents the gods not as literal beings but as symbolic expressions of the elemental powers that shape human experience. The gods are the “great ones” who dwell in the depths of the soul and the world, animating nature, history, and the imagination.

For Jung, this idea resonated deeply with his own intuitions about the nature of the unconscious. He saw in Hölderlin’s gods a poetic articulation of the archetypes – the universal patterns and images that structure the collective unconscious. Like Hölderlin, Jung understood the gods as autonomous psychic factors that possess a numinous energy and significance. They are not mere projections of human fears and desires, but living presences that emerge from the unfathomable depths of the psyche.

In works like “The Hymns of Tubingen” and “Bread and Wine,” Hölderlin evokes the gods as the “highest,” the “holy,” the “blessed” ones who hold sway over human destiny. He speaks of the “spirit of the gods” that moves through all things, animating the cycles of nature and the events of history. For Hölderlin, the task of the poet is to attune himself to this divine presence, to become a vessel for its expression in language.

This idea of the poet as a mediator between the human and divine realms had a profound influence on Jung’s conception of the role of the analyst. Like the poet, the analyst must learn to listen to the language of the unconscious, to become a channel for the numinous energies that seek expression through the psyche. The analyst’s task is not to impose meaning on the patient’s experience, but to midwife the birth of the symbols and images that emerge from the depths.

Hölderlin’s sense of the gods as living presences also informed Jung’s understanding of the importance of myth and ritual. For Jung, myths are not merely primitive superstitions or literary fictions, but symbolic expressions of the archetypal patterns that shape the psyche. They are the “eternal stories” that give form to the numinous energies of the unconscious, providing a language for the soul’s encounter with the divine.

Similarly, rituals are not empty formalities but symbolic enactments of the psyche’s relationship to the archetypal realm. They serve to invoke and channel the numinous energies of the gods, creating a sacred space for the soul’s transformation. In his own therapeutic work, Jung often drew on mythic and ritual elements to create a container for the patient’s journey into the depths.

2.2. The Soul’s Exile and the Longing for Reunion

Another central theme in Hölderlin’s work that deeply influenced Jung and other mystics is the idea of the soul’s exile in the modern world and the longing for reunion with the divine. In poems like “Hyperion’s Song of Fate” and “The Titan,” Hölderlin gives voice to the anguish of the soul’s separation from its divine ground, the sense of homelessness and alienation that pervades the modern condition.

For Hölderlin, this exile is a consequence of the rise of a one-sided rationalism that has severed the soul’s connection to the numinous dimensions of existence. In the modern age, the gods have been banished, reduced to mere fictions or psychological projections. The sacred has been desacralized, the world disenchanted. As a result, the soul wanders in a wasteland of meaninglessness, cut off from the sources of its vitality and purpose.

This theme resonated powerfully with Jung, who saw in the neuroses and spiritual malaise of his patients the symptoms of a profound cultural crisis. For Jung, the modern psyche suffers from a loss of contact with the archetypal realm, the numinous energies that give life depth and significance. Cut off from the wellsprings of the unconscious, the individual becomes trapped in a narrow, ego-bound existence, haunted by feelings of emptiness, alienation, and despair.

In his essay “Wotan,” Jung draws explicitly on Hölderlin to diagnose the spiritual crisis of modernity. He quotes Hölderlin’s lines: “For too long the honor of the heavens has been lacking … For although the gods are living, Over our heads they live, up in a different world.” For Jung, these lines capture the soul’s exile in a disenchanted cosmos, the sense of being cut off from the divine powers that once animated human life.

Like Hölderlin, Jung understood this exile not merely as a personal predicament but as a collective fate. The loss of contact with the numinous is a cultural wound, a rupture in the fabric of meaning that threatens the very foundations of human existence. In a world without gods, without a living sense of the sacred, the soul withers and grows sick, leading to the proliferation of neuroses, addictions, and destructive ideologies.

For both Hölderlin and Jung, the path to healing lies in reconnecting with the archetypal realm, in restoring the soul’s relationship to the divine. This is the task of individuation, the process of psychological and spiritual growth that Jung saw as the central aim of human life. Through the encounter with the unconscious, the individual can begin to bridge the gulf between ego and Self, between the human and the divine.

In Hölderlin’s poetry, this longing for reunion takes the form of a mystical quest, a shamanic journey into the depths of the psyche and the cosmos. The poet becomes a wanderer, a seeker of the lost gods, venturing into the underworld of the soul to retrieve the numinous energies that have been exiled from consciousness. In poems like “The Rhine” and “Patmos,” Hölderlin enacts this descent and return, this death and rebirth of the soul.

For Jung, this poetic journey provided a model for the process of individuation. Like the poet, the individual must confront the shadow, the repressed and rejected aspects of the psyche, in order to integrate them into a larger wholeness. He or she must descend into the unconscious, into the realm of dreams, fantasies, and forgotten memories, in order to retrieve the lost soul.

This process is not a solitary one, but involves a deepening of relationship – to oneself, to others, and to the larger web of life. As the individual begins to reconnect with the archetypal energies of the psyche, he or she also begins to experience a renewed sense of belonging, a re-enchantment of the world. The exile of the soul gives way to a homecoming, a reunion with the divine ground of existence.

2.3. Myth, Symbol, and Poetic Language

Hölderlin’s use of myth, symbol, and poetic language as means of engaging the numinous dimensions of experience had a profound influence on Jung and the development of depth psychology. For Hölderlin, the language of poetry was not merely an aesthetic medium but a sacred tool, a way of attuning the soul to the divine presences that animate the world.

In his essays on poetry, Hölderlin develops a theory of poetic language as a “higher speech,” a mode of expression that transcends the limitations of ordinary discourse. Poetic language, he argues, is not merely referential or descriptive, but evocative and transformative. It has the power to disclose the hidden depths of reality, to make the gods present and palpable.

This idea of language as a vehicle of the sacred had a deep impact on Jung’s understanding of the role of symbol and metaphor in the psyche. For Jung, symbols are not merely signs or representations, but living realities that partake of the numinous energy of the archetypes. They are the “best possible expressions” of the unconscious, the means by which the psyche communicates its deepest truths.

In his essay “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry,” Jung draws extensively on Hölderlin to articulate his vision of the poet as a seer and shaman, a mediator between the human and divine realms. The poet, he argues, is one who has “an unconscious perception of the archetypal background” of existence, who is attuned to the “primordial images” that shape the psyche and the world.

For Jung, this poetic perception is not a matter of intellectual insight or conscious craft, but of surrender and receptivity. The poet must learn to “let things happen,” to become a vessel for the numinous energies that seek expression through him. He must cultivate a state of “active imagination,” a meditative openness to the images and symbols that emerge from the depths of the psyche.

This idea of active imagination became a cornerstone of Jung’s therapeutic method, a way of engaging the unconscious through dialog and creative expression. By attending to dreams, fantasies, and spontaneous images, the individual can begin to uncover the hidden patterns and potentials of the psyche, to integrate the archetypal energies that have been split off from consciousness.

Hölderlin’s use of mythic themes and figures also had a profound influence on Jung’s understanding of the role of myth in the psyche. For Hölderlin, myths were not mere fictions or allegories, but symbolic expressions of the soul’s encounter with the numinous. In his poetry, he draws extensively on Greek mythology to evoke the archetypal forces that shape human destiny – the gods and heroes, the fates and furies, the sacred places and events.

Jung saw in Hölderlin’s poetic use of myth a model for the psychological function of mythic narratives. Myths, he argued, are not primitive superstitions or outdated beliefs, but timeless patterns that structure the psyche and give form to the numinous energies of the unconscious. They are the “eternal stories” that guide the soul’s journey of individuation, providing a language for the encounter with the archetypal realm.

In his own writings and therapeutic work, Jung often drew on mythic themes and figures to illuminate the dynamics of the psyche. He saw in the hero’s journey a template for the process of individuation, in the divine child a symbol of the Self, in the Great Mother an image of the archetypal feminine. By engaging with these mythic patterns, the individual can begin to align the ego with the larger purposes of the Self, to find meaning and direction in the unfolding of life.

For both Hölderlin and Jung, the language of myth and symbol was essential to the task of re-enchanting a disenchanted world, of restoring a sense of the sacred to human existence. In a time of spiritual crisis and fragmentation, the poetic imagination offered a way of reconnecting with the numinous ground of being, of bridging the gulf between the human and the divine. By attending to the symbols and stories that emerge from the depths of the soul, the individual can begin to find a new orientation, a new sense of purpose and belonging in a world that has grown cold and meaningless.

This vision of the transformative power of poetic language and mythic imagination has had a lasting impact on the field of depth psychology and beyond. It has inspired generations of thinkers and artists to explore the creative and healing potential of the unconscious, to seek out the lost gods and forgotten wisdom of the soul. From the archetypal psychology of James Hillman to the mythopoetic men’s movement of Robert Bly, Hölderlin’s legacy continues to resonate in the contemporary quest for meaning and wholeness.

2.4. The Poet as Mediator and Prophet

Hölderlin’s vision of the poet as a mediator between the human and divine realms, and as a prophet of a new mythos, had a significant influence on Jung and other modern mystics. For Hölderlin, the poet was not merely a literary figure but a sacred calling, a vocation of the highest order. The poet, he believed, was one who had been “called” by the gods to serve as a vessel for their numinous energies, to give voice to the eternal truths that lie hidden in the depths of the soul.

In his novel “Hyperion,” Hölderlin presents the poet as a heroic figure, a wanderer and seeker who ventures into the unknown to retrieve the lost wisdom of the ages. Hyperion, the protagonist, is a young Greek who yearns to revive the ancient spirit of his homeland, to create a new mythology that can heal the fragmentation and despair of the modern world. He is a visionary and a prophet, a “priest of the divine” who serves as a mediator between the mortal and immortal realms.

This image of the poet as a sacred mediator had a profound influence on Jung’s understanding of the role of the artist and the mystic in modern society. For Jung, the poet and the prophet were archetypal figures who served a vital function in the spiritual economy of the psyche. They were the ones who ventured into the depths of the unconscious, who confronted the numinous powers that lie hidden there, and who returned with new visions and revelations for the community.

In his essay “Psychology and Literature,” Jung writes that the poet is “the voice of the collective unconscious,” the one who gives expression to the archetypal truths that lie dormant in the psyche of the race. The poet, he argues, is not a mere entertainer or aesthete, but a “seer” and a “shaper of the soul,” one who has the power to transform and redeem the spiritual malaise of the age.

This idea of the poet as a redemptive figure was central to Hölderlin’s own self-understanding and sense of mission. In his letters and essays, he often speaks of the “holy task” of poetry, the sacred duty of the poet to “heal” and “rejuvenate” the world through the power of language. For Hölderlin, the poet was not only a mediator between the human and divine realms, but also a prophet of a new age, a harbinger of a future in which the gods would once again dwell among mortals.

This prophetic dimension of Hölderlin’s poetic vocation had a significant impact on Jung’s own sense of the role of depth psychology in the modern world. Like Hölderlin, Jung saw himself as a kind of prophet and healer, one who had been called to address the spiritual crisis of the age. In his writings and lectures, he often spoke of the need for a new mythology, a new spiritual vision that could reorient the modern psyche and restore a sense of meaning and purpose to human existence.

For Jung, this new mythology could not be a mere revival of old forms, but had to emerge from the depths of the collective unconscious, from the archetypal wellsprings of the psyche. It had to be a living myth, a dynamic and transformative vision that could speak to the unique challenges and potentials of the modern age. And it had to be grounded in a new understanding of the nature of the psyche, a recognition of the creative and numinous powers that lie hidden within the soul.

In this sense, Jung saw depth psychology as a kind of “new dispensation,” a spiritual and intellectual revolution that could help to midwife the birth of a new era in human history. Like Hölderlin’s poet-prophet, the depth psychologist was called to venture into the unknown, to retrieve the lost wisdom of the ages, and to bring forth new visions and revelations for the healing of the world.

This prophetic and visionary dimension of Jung’s work has had a profound influence on the development of modern spirituality and the human potential movement. From the transpersonal psychology of Stanislav Grof and Ken Wilber to the archetypal activism of Matthew Fox and Andrew Harvey, Jung’s legacy has inspired generations of seekers and mystics to take up the task of cultural transformation, to become midwives of a new mythos for the modern age.

In this sense, Hölderlin’s influence on Jung and modern mysticism extends far beyond the realm of poetry and aesthetics. It is a call to a higher vocation, a summons to serve as mediators and prophets of the divine in a world that has grown cold and disenchanted. It is an invitation to venture into the depths of the soul, to retrieve the lost gods and forgotten wisdom of the ages, and to bring forth new visions and revelations for the healing of the world.

2.5. Madness as Spiritual Initiation

One of the most striking and controversial aspects of Hölderlin’s life and work was his struggle with madness, which he experienced as a kind of spiritual initiation into the depths of the psyche. In the last decades of his life, Hölderlin suffered from a severe mental illness that left him unable to function in society, living in a tower in the care of a carpenter’s family. Many of his contemporaries saw his madness as a tragic fate, a cruel irony that had befallen one of the greatest poets of the age.

But for Jung and other modern mystics, Hölderlin’s madness was not a mere pathology but a sacred calling, a initiatory journey into the underworld of the soul. In his essay “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry,” Jung writes that Hölderlin’s madness was “a higher form of existence,” a state of heightened sensitivity and spiritual awareness that allowed him to penetrate the veil of ordinary reality and access the numinous realms of the psyche.

For Jung, Hölderlin’s madness was a kind of shamanic initiation, a descent into the depths of the unconscious that paralleled the mythic journeys of the hero and the mystic. Like the shaman who ventures into the spirit world to retrieve lost souls, or the mystic who plunges into the abyss of the divine, Hölderlin had embarked on a perilous journey into the unknown, a quest for the ultimate meaning and purpose of existence.

In this sense, Jung saw Hölderlin’s madness not as a failure or a weakness, but as a mark of his spiritual greatness,

Bibliography:

Avens, R. (1980). Imagination is Reality: Western Nirvana in Jung, Hillman, Barfield, and Cassirer. Spring Publications.

Barfield, O. (2011). What Coleridge Thought. Barfield Press UK.

Bly, R. (1980). News of the Universe: Poems of Twofold Consciousness. Sierra Club Books.

Corbin, H. (1998). The Voyage and the Messenger: Iran and Philosophy. North Atlantic Books.

Giegerich, W. (2012). What is Soul? Spring Journal, Inc.

Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, Language, Thought. Harper & Row.

Heidegger, M. (1984). Hölderlin’s Hymn “The Ister”. Indiana University Press.

Hillman, J. (1989). A Blue Fire: Selected Writings. Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (1991). Re-Visioning Psychology. HarperPerennial.

Hölderlin, F. (1990). Hyperion and Selected Poems. The Continuum Publishing Company.

Hölderlin, F. (2004). Essays and Letters. Penguin Classics.

Jung, C. G. (1967). Alchemical Studies. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1966). The Spirit in Man, Art, and Literature. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Pantheon Books.

Kingsley, P. (2018). Catafalque: Carl Jung and the End of Humanity. Catafalque Press.

Otto, R. (1958). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford University Press.

Rilke, R. M. (1995). Ahead of All Parting: The Selected Poetry and Prose of Rainer Maria Rilke. Modern Library.

Rilke, R. M. (2001). Duino Elegies & The Sonnets to Orpheus. Vintage International.

Robertson, R. (2018). Indra’s Net and the Midas Touch: Living Sustainably in a Connected World. Aster.

Romanyshyn, R. D. (2013). The Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind. Spring Journal, Inc.

Ryan, J. S. (2002). Heidegger’s Hölderlin and the Subject of Poetic Language. Fordham University Press.

Sardello, R. (2008). Silence: The Mystery of Wholeness. North Atlantic Books.

Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court.

Voss, A. (2019). The Imaginal Cosmos: Astrology, Divination and the Sacred. Rubedo Press.

Zimmermann, J. (2015). Hermeneutics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Jungian Innovators

0 Comments