Why do People Join Cults and Believe Propaganda?

The Internet and the Illusion of Truth

When the internet first emerged, many believed it would solve our political problems by providing universal access to truth. I remember these days myself and there was a techno-libertarian-utopianism that pervaded the early internet. The idea was that, with the ability to bypass traditional gatekeepers like the government and the news media, people would be able to find and spread accurate information, leading to a more informed electorate and better political decisions. All the world’s problems would be fixed.

However, this optimistic view was based on a naive understanding of human psychology. It assumed that when presented with the truth, people would readily accept it and act accordingly. In reality, we are creatures with a strong tendency to insulate ourselves from uncomfortable truths that mean we need to change our beliefs or behavior. The modern internet is proof of this.

What the internet actually did was give us instant and endless data that confirmed anything that we wanted to think. Humans are drawn to actively seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs and biases, a phenomenon known as confirmation bias. The internet, rather than being a tool for finding objective truth, has often become an echo chamber where we can find endless support for whatever we want to believe, no matter how misguided or factually inaccurate.

If you want to believe the Earth is flat, a quick Google search will provide you with hundreds of reasons to support that belief. If you’re skeptical of vaccines, you can easily find a community of like-minded individuals sharing articles and anecdotes that reinforce your doubts. The internet has made it easier than ever to do “research” that consists of simply collecting data points that align with what we already think. This primed the scene for new forms of passive political and scientific propaganda that corrupted our ability to make meaningful personal and meaningful changes as a society.

What is Propaganda?

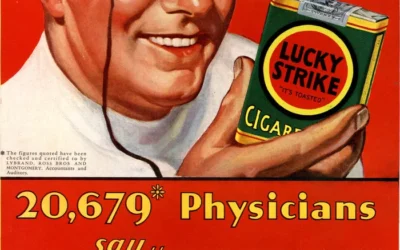

When we think of propaganda we might think of a Nazi poster or a USSR show trial. However propaganda can be a pernicious passive force that goes beyond mere lies or government coercion. It is a co-opting of the meaning-making processes, both religious and scientific, within a society. The goal of propaganda is to create a self-reinforcing feedback loop where individuals become trapped within a system that is ineffective, yet they are unable to see beyond its confines.

In the information age, people can only be actively lied to or told untruths a certain number of times before they begin to catch on. However, for a propaganda state to be truly effective, it must convince people that the only way to achieve their desired outcome is through a specific process. When evidence arises that suggests the process is not working, the propaganda machine spins this as proof that the process is, in fact, functioning as intended.

This creates a powerful self-reinforcing feedback loop. As people invest more time, energy, and resources into the ineffective system, they become increasingly resistant to evidence that contradicts their beliefs. They may interpret failures as temporary setbacks or even as signs that they need to double down on their efforts through a useless ritual or ineffective mode of action. This feedback loop can be incredibly difficult to break, as it requires individuals to question the very foundations of their worldview.

Examples of this tactic abound in various facets of life. Religion, politics, advertising, abusive therapy, coercive self-help models, and cults all employ this form of propaganda. The essence of propaganda is to convince a group of people that an ineffective system is the only possible way to achieve success. When this belief takes hold, even highly intelligent individuals struggle to see beyond the confines of the system they are trapped within. They may view alternative approaches as interesting curiosities but ultimately irrelevant to solving the problem at hand, as they are convinced that only one solution exists to solve.

Any time that we are convinced that there is only one way to accomplish a political, religious or personal objective we are beginning this process. Anytime we decide that EVEN though our current method has failed multiple times that it is still the only way to accomplish our goal we are in the middle of the process. Once we start blaming others or circumstances for our own failed conceptualization of the world failing to pan out we are deeply entrenched in it.

Effective passive propaganda diminishes pattern recognition, even in exceptionally intelligent people. This is because they are operating under the implicit assumption that the only way to achieve their goal is through a method that has failed repeatedly in the past. They fail to notice the pattern of failure, falling into the trap of insanity: doing the same thing over and over while expecting a different result.

The self-reinforcing nature of propaganda makes it incredibly difficult to combat. As evidence mounts that the system is not working, true believers often become more entrenched in their views. They may see the lack of success as a sign that they are not trying hard enough or that they need to have more faith in the process, or that others should participate in their way of being more. This creates a vicious cycle where failure is interpreted as a reason to invest even more heavily in the ineffective system, further perpetuating the feedback loop.

Micro Mirrors Macro

When we are trying to self-evidently prove something that is fundamentally untrue or impossible in our personal lives and relationships, it is a neurosis. This could include the belief that we are entitled to special treatment, that our emotions are someone else’s responsibility, or even worse, that we are victims of circumstance with no agency over our lives.

Often, we engage in these neurotic patterns to protect ourselves from accepting some greater truth about ourselves, the world, or the relationship between the two. When we invest all of our psychological energy into maintaining this neurosis, and our identity becomes inseparable from it, then it can be classified as a personality disorder.

It’s important to understand that we don’t participate in these pathological modes of functioning because we are inherently bad or beyond help. Anyone has the capacity to change. Rather, we do so to protect ourselves from the discomfort of uncertainty.

The Discomfort of Uncertainty

Sitting with uncertainty is a hallmark of maturity and psychological adulthood. It means being able to tolerate ambiguity, to resist the urge for premature closure, and to remain open to new information and possibilities.

However, as mythologist Joseph Campbell pointed out, the function of mythology (and by extension, many belief systems) is to protect us from uncertainty. By providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the world, mythology offers a sense of order, meaning, and predictability in the face of life’s chaos and mystery.

The problem arises when our need for certainty becomes so great that we cling to these frameworks even when they are contradicted by reality. We may double down on our beliefs, engage in increasingly convoluted rationalizations, or simply ignore any information that doesn’t fit our preconceived notions.

The Neurotic Society

What happens when these neurotic patterns of thinking and behaving are not just individual quirks, but are woven into the very fabric of our social institutions?

We end up with a society that is fundamentally out of touch with reality. A society that cannot adapt to changing circumstances, that cannot learn from its mistakes, and that continues to invest in systems and strategies that have been proven ineffective.

We see this in the realm of politics, where ideological purity often trumps pragmatic problem-solving. We see it in the realm of religion, where dogmatic adherence to ancient texts can override compassion and reason. We see it in the realm of economics, where the myth of endless growth persists despite mounting environmental and social costs.

In each case, the neurotic patterns that individuals use to protect themselves from uncertainty are mirrored and magnified at the societal level. The result is a kind of collective insanity, where we keep doing the same things over and over, expecting different results.

Breaking the Cycle

How do we break out of these self-perpetuating cycles of neurosis and dysfunction? The first step is awareness. We need to be honest with ourselves about the ways in which we are engaging in these patterns, both individually and collectively.

This requires a willingness to sit with the discomfort of uncertainty, to question our assumptions, and to be open to alternative perspectives. It means developing a more flexible and adaptive relationship with our beliefs, one that allows for growth and change in response to new information.

At a societal level, it means creating institutions and systems that are designed for learning and adaptation rather than for the maintenance of the status quo. It means fostering a culture of critical thinking, open dialogue, and intellectual humility.

None of this is easy. The pull of certainty is strong, and the discomfort of uncertainty can be overwhelming. But the alternative is to remain trapped in cycles of dysfunction, unable to effectively address the complex challenges we face.

The Insidious Nature of Predatory Systems

Predatory systems, whether they take the form of cults, exploitative relationships, manipulative sales tactics, or personality disorders, all share a common thread: they seek to blend the diagnosis of a problem with the prescription of a specific solution. This is a key red flag to watch out for when evaluating the legitimacy of any system or individual offering help.

These systems often begin by establishing a powerful emotional connection with their target. The leader or influencer may demonstrate an uncanny ability to understand and articulate the target’s deepest insecurities, fears, and desires. This “aha moment” of feeling seen and understood can be incredibly seductive, making the target more receptive to the prescribed solution.

However, this is where the manipulation begins. The predatory system will insist that the only way to solve the identified problem is through the specific solution they offer. They will attempt to create a false link between the accuracy of their diagnosis and the effectiveness of their prescription, suggesting that because they understood the problem so well, their solution must be the only valid one.

This is a dangerous fallacy. There are always multiple options for solving a problem. A legitimate mentor or society will encourage the exploration of different solutions, providing evidence and allowing for personal choice. In contrast, a predatory system will insist on a single path forward, often using pressure, guilt, or fear to discourage questioning or deviation.

The self-reinforcing nature of these systems makes them particularly difficult to escape. As the target invests more time, money, and emotional energy into the prescribed solution, they become increasingly resistant to evidence that contradicts its effectiveness. Failures are reframed as a lack of commitment or faith, rather than a flaw in the system itself. This creates a vicious cycle where the target feels compelled to double down on their investment, even as it leads them further away from genuine healing or growth.

The Role of Uncertainty and Dependency

Predatory systems also exploit our discomfort with uncertainty and our desire for clear, simple solutions. They present a world that is black and white, where there are clear good guys and bad guys, right answers and wrong answers.

This simplistic worldview can be comforting, especially when we are facing complex or ambiguous problems in our lives. It offers a sense of certainty and security in an uncertain world.

However, this certainty comes at a cost. By buying into the simple solutions offered by predatory systems, we often fail to develop the skills and capacities needed to navigate complexity and ambiguity. More importantly we lose the ability to hold authority in our own lives and to make our own evaluations about what works. We become dependent on the system for guidance and direction, losing touch with our own inner resources and wisdom.

This dependency is often reinforced through the use of fear and intimidation. Predatory systems may warn of dire consequences for questioning or leaving the group. They may paint the outside world as dangerous or corrupt, creating a sense that there is no safe haven beyond the confines of the system.

What’s more is that abusive systems often offer a false sense of agency and authority by making the other members complicit or responsible for abuse. The psychological reasons that abusers do this are two fold. On one hand it makes followers feel like they are in charge or in control even though they are doing the bidding of the cult leader. On the other hand they make members less likely to leave as facing the consequences of the abuse they have caused creates more cognitive dissonance and potential guilt and shame if they question the morality of what they are doing.

Breaking Free

Breaking free from a predatory system can be a difficult and painful process. It often involves a period of disillusionment and grief as we come to terms with the fact that we have been misled or exploited.

However, this disillusionment is also an opportunity for growth and empowerment. By seeing through the illusions of the predatory system, we can begin to reclaim our own agency and autonomy.

This process requires us to develop a more nuanced and complex understanding of ourselves and the world around us. It means learning to tolerate uncertainty and ambiguity, to think critically and independently, and to trust in our own judgment and intuition. Often this means sitting with the guilt and shame of past actions.

It also requires building a support system outside of the predatory system to consider other points of view. This may involve reconnecting with friends and family members, seeking out new communities and relationships, or working with a therapist or counselor who can provide guidance and support.

How Predatory Systems Co-opt the Psyche

At their core, predatory systems work by hijacking different aspects of our consciousness or psyche to serve the wrong functions. They exploit our natural instincts and tendencies, both subjective and objective, in order to manipulate and control us.

On the subjective side, predatory systems often target our symbolic and emotional instincts. Religion, for example, serves a subjective function in providing meaning, comfort, and spiritual guidance. However, when a religious leader claims that faith alone can cure cancer, they are co-opting this subjective instinct to serve a literal, material function it is not equipped for. This can lead to devastating consequences, as people may forego necessary medical treatment in favor of ineffective spiritual remedies.

Similarly, abusive relationships often involve the manipulation of emotional instincts. An abuser may play on their victim’s desire for love, acceptance, and belonging, using these subjective needs to trap them in a cycle of dependence and control. By blending emotional fulfillment with material control, the abuser co-opts the victim’s psyche to serve their own interests.

On the objective side, predatory systems may exploit our literal, empirical instincts. Politics, for example, is meant to serve a material function in representing our interests and enacting policies that benefit society. However, when politicians or pundits make primarily emotional appeals, portraying candidates as heroic figures or saviors, they are co-opting our symbolic instincts in a domain where they don’t belong.

This blending of the subjective and objective can be particularly insidious in the realm of politics. We may be swayed by charisma or inspirational rhetoric, forgetting that a politician’s true job is to represent our material interests through concrete action. By confusing our emotional needs with our practical ones, predatory political systems can lead us to make choices that go against our own best interests.

In all of these cases, the key to manipulation is blurring the lines between the subjective and objective functions of our psyche. When we allow our symbolic instincts to be exploited for literal ends, or our material needs to be swayed by emotional appeals, we become vulnerable to predatory systems.

To protect ourselves, we must strive to keep these different aspects of our psyche in their proper domains. We should seek emotional and spiritual fulfillment through channels equipped to provide it, while relying on empirical evidence and practical considerations when making decisions about our material well-being. By maintaining these boundaries and exercising critical thinking, we can resist the manipulative pull of predatory systems and maintain autonomy over our own minds and lives.

When Prophecy Fails: Festinger’s UFO Cult Study

One of the most famous studies in the history of cognitive dissonance theory was conducted by Leon Festinger, the psychologist who first proposed the theory. In the 1950s, Festinger and his colleagues infiltrated a UFO cult known as the Seekers, led by a woman named Dorothy Martin (pseudonym used in the study was Marian Keech).

Martin claimed to have received messages from extraterrestrial beings, known as the Guardians, who warned her of a great flood that would end the world on December 21, 1954. The Guardians promised that they would rescue the true believers by swooping them away in a flying saucer.

Festinger and his team saw this as a unique opportunity to study what would happen when a deeply held belief was definitively disproved. They hypothesized that when the prophecy failed (i.e., when the world didn’t end and the UFO didn’t come), the members of the group would experience intense cognitive dissonance.

Increased Fervor and Proselytization

Fascinatingly, what they observed was that for many members of the group, the failure of the prophecy actually seemed to strengthen their belief in the cult’s teachings. Rather than abandoning their beliefs, they came up with rationalizations to explain away the discrepancy.

Some suggested that the group’s faith had saved the world from destruction. Others claimed that the Guardians had given them a new date for the end of the world. Many became even more fervent in their beliefs and began actively proselytizing, trying to convert others to their way of thinking.

Festinger and his team argued that this response was a way of reducing the cognitive dissonance the cult members experienced. By convincing others to believe as they did, they could gain social support for their beliefs, making them feel less alone and less confused.

The Backfire Effect

This study provided a powerful demonstration of what has come to be known as the “backfire effect” – the phenomenon where trying to disprove a belief can actually strengthen it.

When we are deeply invested in a belief, encountering contradictory evidence can create a state of cognitive dissonance. To resolve this dissonance, we may cling even more strongly to our original belief, finding ways to discount or rationalize away the contradictory information.

This effect has been observed in many contexts beyond UFO cults. It can happen with political beliefs, conspiracy theories, and even personal health behaviors. When confronted with information that challenges a deeply held belief, people may become defensive, dismissive, or even hostile.

Implications for Persuasion and Belief Change

The backfire effect has important implications for anyone trying to change others’ beliefs or behaviors. It suggests that simply presenting people with facts that contradict their beliefs is often not an effective strategy, and can even be counterproductive.

Instead, a more nuanced approach is needed, one that takes into account the psychological factors that drive belief formation and maintenance. This might involve strategies like finding common ground and building rapport before challenging beliefs, acknowledging the emotional and identity-based reasons why someone might hold a belief, presenting new information in a way that doesn’t trigger defensiveness, and helping people find alternative ways to meet the psychological needs that their belief serves.

By understanding the backfire effect and the role of cognitive dissonance in belief maintenance, we can develop more effective strategies for persuasion and belief change. This is particularly important in an era where misinformation and polarization are rampant, and where many of the world’s most pressing problems require changes in collective beliefs and behaviors.

Festinger’s UFO cult study remains a landmark in the field of social psychology, offering profound insights into the complex and often counterintuitive ways that our minds respond to challenges to our beliefs. By taking these insights to heart, we can become more skillful in navigating the landscape of belief and more effective in fostering positive change in ourselves and in the world.

The Persistence of Belief

The backfire effect, as demonstrated in Festinger’s study, is a testament to the incredible power of belief. Our beliefs are not just intellectual constructs; they are deeply intertwined with our identities, our emotions, and our social relationships.

When a belief is challenged, it’s not just an idea that’s being questioned, but our very sense of self. This is why the cognitive dissonance that arises from a challenged belief can be so uncomfortable, and why we are so motivated to reduce it.

However, the strategies we use to reduce this dissonance – rationalization, doubling down, seeking social support – are not always in service of truth or personal growth. In fact, they can keep us stuck in false or limiting beliefs, preventing us from adapting to new information and changing circumstances.

This is where the real work of belief change happens. It’s not just about being presented with new facts or arguments, but about doing the deep psychological work of examining our beliefs, understanding their emotional and social roots, and finding ways to update or let go of them when they no longer serve us.

This is a difficult and often painful process. It requires courage, self-reflection, and a willingness to sit with uncertainty and discomfort. But it is also a path to greater freedom, authenticity, and effectiveness in the world.

Morality, Ethics, and Cognitive Dissonance

The relationship between moral beliefs and actual behavior is often more complex and contradictory than it may appear on the surface. A prime example of this is the finding that individuals who see divorce as a sin, but not against common morality, are more likely to get divorced than those who view divorce as morally acceptable.

This seeming paradox can be understood through the lens of cognitive dissonance and the psychological mechanisms of repression and projection. When someone holds a strong moral belief, such as the idea that divorce is wrong, but also harbors doubts or insecurities about their own ability to maintain a marriage, they may experience a deep internal conflict.

Rather than confronting these doubts and dealing with them directly, they may repress these feelings and project them onto others. This can manifest as a strong outward condemnation of divorce and a need to broadcast to others that it is wrong. By focusing on the supposed moral failings of others, they avoid having to confront their own uncertainties and potential shortcomings.

This dynamic is often amplified in individuals who see themselves as highly morally ordered and an example for others to follow. The need to maintain this self-image can lead to a rigid adherence to moral codes, not because these codes are necessarily working for the individual, but because any deviation would threaten their status and authority.

The Dangers of Moral Absolutism

This phenomenon can be particularly problematic in missionary and religious communities, where members are often held to strict moral standards and encouraged to see themselves as a “city on a hill” – a shining example for the rest of the world to follow.

In these contexts, admitting to personal struggles or questioning the validity of certain moral rules can be seen as a weakness or a threat to the community’s special status. As a result, individuals may feel pressured to repress their doubts and present a facade of perfect adherence to the moral code.

This can create an environment where abuses can flourish unchecked. If members feel unable to voice their concerns or admit to their own imperfections, they may also be less likely to report or confront abusive behaviors in others. The need to maintain the illusion of moral superiority can override the imperative to address real harms.

The Value of Honesty and Imperfection

In contrast, communities that encourage honest dialogue and acknowledge the inherent imperfections of all humans tend to be healthier and more resilient. When individuals feel safe to express their doubts, struggles, and failures without fear of judgment or ostracism, they are more likely to seek help, to hold each other accountable, and to work together towards personal and collective growth.

This approach recognizes that morality is not about adhering to a set of rigid, external rules, but about engaging in a continual process of self-reflection, empathy, and adjustment. It understands that we are all flawed and that true moral strength comes not from pretending to be perfect, but from being willing to confront our imperfections and learn from them.

Implications for Moral Reasoning

These insights have profound implications for how we think about morality and ethics. They suggest that our moral beliefs and behaviors are often shaped by complex psychological factors, including our own insecurities, fears, and desires for status and control.

To engage in truly ethical reasoning, we must be willing to confront these underlying factors and to question the motives behind our moral stances. We must be open to the possibility that what we proclaim as moral absolutes may be, in part, a reflection of our own unresolved issues and biases.

This doesn’t mean that all moral codes are invalid or that we should refrain from making moral judgments. But it does mean approaching morality with a degree of humility, self-awareness, and openness to dialogue. It means recognizing that being a good person is not about perfect adherence to a set of rules, but about the willingness to honestly examine oneself, to empathize with others, and to continually strive for growth and understanding.

Moral Suasion and Cooperation

In 2013, researchers Battigalli, Charness, and Dufwenberg conducted a study that sheds light on the complex relationship between moral beliefs, actions, and expectations of others’ behavior. The study, published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, used a classic economic game theory scenario known as the prisoner’s dilemma.

In the prisoner’s dilemma, two participants have to choose whether to cooperate with each other or to defect (i.e., to betray the other for personal gain). The optimal outcome for both participants is achieved if they both choose to cooperate. However, if one participant defects while the other cooperates, the defector stands to gain more individually. If both participants defect, they both lose out.

In Battigalli et al.’s study, some participants were given a moral framing before playing the game. They were told that cooperating was the right thing to do from a moral perspective. Other participants were not given this moral framing.

After making their decision to either cooperate or defect, participants were asked to predict what they thought their partner in the game had chosen to do.

The results of the study were fascinating and counterintuitive. Among the participants who were given the moral framing and then chose to defect, there was a higher expectation that their partner would choose to cooperate compared to the defectors who weren’t given the moral framing.

In other words, the participants who acted against the moral frame they were given were more likely to expect moral behavior from their partner. The researchers interpret this as a form of guilt projection. By expecting their partner to behave morally (i.e., to cooperate), the participants who chose to defect could alleviate some of the cognitive dissonance and guilt they felt about their own immoral action.

This finding suggests that when we act in a way that contradicts our moral beliefs, we may unconsciously project our own sense of moral obligation onto others. We expect them to uphold the moral standard that we ourselves have violated, possibly as a way to minimize our own sense of guilt or cognitive dissonance.

This study provides a compelling demonstration of the complex psychological dynamics at play in moral decision-making. It shows that our beliefs about what is right and wrong can influence not only our own actions but also our expectations of others’ behavior.

Moreover, it highlights the role of cognitive dissonance in shaping these expectations. When we act against our own moral convictions, the resulting psychological discomfort can lead us to engage in mental maneuvers designed to minimize our sense of guilt or inconsistency. Projecting our moral standards onto others is one such maneuver.

This has important implications for understanding moral behavior in various contexts. In interpersonal relationships, in the workplace, and in society at large, we may often encounter situations where people’s actions don’t align with their stated moral beliefs. Understanding the psychological mechanisms behind this apparent hypocrisy – such as guilt projection and cognitive dissonance reduction – can help us navigate these situations with more insight and empathy.

It’s important to note that the psychological dynamics illustrated in this study don’t necessarily imply deliberate hypocrisy or bad faith on the part of the moral defectors. Rather, they highlight the often unconscious ways in which our minds attempt to maintain a sense of moral consistency and integrity, even in the face of contradictory evidence.

This doesn’t excuse immoral behavior, but it does suggest a more nuanced view of moral inconsistency. Rather than simply condemning those who fail to live up to their own moral standards, we can strive to understand the complex psychological factors that contribute to these failures.

This understanding, in turn, can inform more effective strategies for encouraging moral behavior and reducing the incidence of moral transgressions. By creating environments that reduce cognitive dissonance, that encourage honest self-reflection, and that provide support for acting in accordance with one’s values, we can help individuals align their actions more consistently with their moral beliefs.

The Normalization of Arbitrary Rules

These findings highlight a broader issue: when people are taught contra-logical or arbitrary rules that are normalized within their political, religious, or cultural group, they can struggle to differentiate between common sense and cultural bias.

When a belief system includes rules or norms that contradict logical reasoning or evidence, adherents of that system may find themselves engaging in cognitive dissonance on a regular basis. They may have to rationalize away the contradictions between their beliefs and reality, leading to a distorted view of the world.

Over time, this constant rationalization can blur the lines between what is truly common sense and what is a product of their specific cultural conditioning. They may start to see their arbitrary cultural norms as universal truths, and struggle to understand or empathize with those who don’t share these norms.

This can lead to a host of problems, from difficulty in adapting to new information and circumstances, to inter-group conflict and misunderstanding. It can also make people more susceptible to manipulation, as they may be less able to critically evaluate ideas that come from within their own cultural context.

Understanding this dynamic is crucial for breaking free from the grip of cognitive dissonance and developing a more objective, reality-based worldview. By learning to recognize when our beliefs are based on arbitrary cultural norms rather than logic and evidence, we can start to decouple our sense of morality and truth from the accidents of our cultural conditioning.

This is not an easy process, as it requires questioning deeply ingrained beliefs and norms. But it is a necessary step towards developing a more coherent, adaptive, and compassionate approach to navigating the complexities of the world.

By recognizing the ways in which normalized arbitrary rules can distort our thinking, we can start to build a worldview that is grounded in reality, guided by reason, and open to learning from the diversity of human experience. This, ultimately, is the path to personal growth, social harmony, and a more enlightened society.

Escaping the Comfort of Illusion

As T.S. Eliot once said, human beings can only bear a little bit of reality. We all have a natural tendency to gravitate towards the parts of our psyche that we’re more comfortable with, and to project those onto the world around us, even when they don’t fit.

This tendency is what makes us vulnerable to cults, abusive relationships, and manipulative advertising or politics. These systems offer us a version of reality that aligns with our desires and beliefs, allowing us to stay stuck in a comforting illusion of how we think the world works.

But just as escaping a cult requires facing the uncomfortable truth that one’s beliefs were misplaced, overcoming a personality disorder, improving relationships, or graduating from therapy all require a willingness to accept reality as it is, not as we wish it were.

The Stages of Grief as a Path to Acceptance

The stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance – are not just a response to loss, but a common pattern we go through when faced with any reality that challenges our worldview.

In denial, we reject the challenging information outright. We refuse to believe that our worldview could be wrong, that the systems we trusted could be flawed. Denial is a defense mechanism that allows us to avoid the pain of having our beliefs shattered. It’s a way of clinging to the comfort of our old understanding, even in the face of contradictory evidence.

Anger is a way of externalizing the inner turmoil we feel when our beliefs are challenged. We lash out at the source of the challenging information, whether it’s a person, a group, or an idea. Anger allows us to avoid introspection by focusing our energy outward. It’s also a way of trying to assert control over a situation that feels threatening and chaotic. By getting angry, we create the illusion that our emotions have the power to change reality to fit our expectations.

In bargaining, we try to find a way to fit the new information into our existing beliefs. We look for loopholes, exceptions, or compromises that will allow us to maintain our worldview while acknowledging the challenging evidence. Bargaining is an attempt to negotiate with reality, to find a middle ground between what we want to believe and what the facts are telling us. It’s a way of avoiding the full implications of the truth.

Depression sets in when we can no longer maintain our denial, anger, or bargaining. We are forced to confront the reality that our old beliefs were misguided or inadequate. This realization can be profoundly disorienting and painful. We may feel lost, hopeless, or betrayed. Depression is a natural response to the loss of a cherished worldview. It’s a time of grieving, of coming to terms with the fact that the world is not as we thought it was.

But it is only in acceptance that we truly begin to heal and grow. Acceptance doesn’t mean that we like the new reality or that we don’t feel sadness or regret. Rather, it means that we have come to terms with the truth and are ready to move forward based on what is, not what we wish were true.

Accepting reality means letting go of our attachment to how we think things should be, and embracing how they actually are. It’s a recognition that the systems we were taught, the beliefs we held, do not always function the way we thought they did. Acceptance requires humility, flexibility, and resilience. It means being open to new information, even when it challenges our preconceptions.

It’s important to note that these stages are not always linear. We may move back and forth between them, or get stuck in one stage for a long time. And the process of grieving and accepting a challenging reality is not always a one-time event. As we continue to learn and grow, we may face many moments where we have to let go of old beliefs and adapt to new understandings.

But by recognizing these stages and understanding their psychological functions, we can be more mindful of our own reactions when faced with challenging information. We can catch ourselves in moments of denial, anger, or bargaining, and consciously choose to move towards acceptance. By doing so, we open ourselves up to personal growth and a more authentic, adaptive relationship with reality.

This acceptance of reality is the foundation of all meaningful change, both personal and societal. It’s what allows the abuse victim to leave their abuser, the addict to seek help, the failed entrepreneur to learn from their mistakes.

On a larger scale, it’s what drives social and scientific progress. Every major advancement in human understanding, from the recognition that the Earth orbits the sun, to the acceptance of evolution, to the fight for civil rights, has required a willingness to let go of comforting but inaccurate beliefs and to align our understanding with observable reality.

The Role of Therapy

A key role of therapy is to help individuals face and accept reality. This is not always a comfortable process. It can be painful to let go of long-held beliefs, to acknowledge the ways in which our perceptions have been distorted.

But it is through this process that real healing and growth occurs. By helping individuals escape the feedback loops of denial and distortion, therapy empowers them to build a more grounded, authentic, and adaptive relationship with reality.

This is not to say that emotions and subjective experiences are unimportant. Our feelings are real and valid. But they are not always reliable guides to objective truth. Part of emotional maturity is learning to honor our emotions while also recognizing their limits.

In a world filled with comforting illusions and manipulative narratives, accepting reality is a revolutionary act. It requires courage, humility, and a willingness to let go of cherished beliefs even if this is scary or overwhelming.

Joseph Campbell put this candidly when giving a talk about the hero’s journey to one audience member who asked why looking inward at these dynamics was necessary. “It’s not” Campbell told him “a dog lives a very happy life… but only as a dog”. Campbell’s point is caustic but true. Most people are led around their whole lives on their own or others’ leashes. They never grow up and never face reality. But to face reality is adult.

This is the path of growth, the path of progress, the path of authentic living. It is not always easy, but it is always necessary. In the end, reality will always assert itself. Our choice is whether to meet it with open eyes and an open mind, or to resist it at the cost of our own growth and wellbeing.

0 Comments