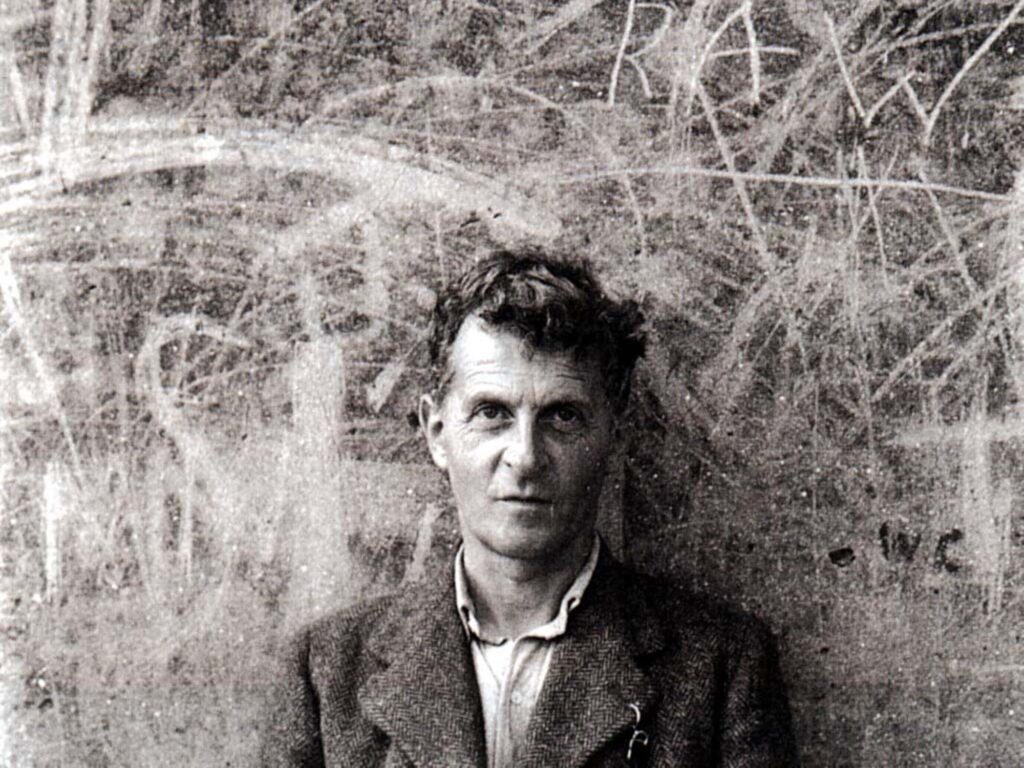

What does Ludwig Wittgenstein have to do with Psychology?

Ludwig Wittgenstein, a towering figure in 20th-century philosophy, left a profound impact on our understanding of language, meaning, and the human experience. His groundbreaking ideas, particularly those presented in his posthumously published work, “Philosophical Investigations,” offer invaluable insights that can be applied to various fields, including psychology and psychotherapy. In this extensive blog post, we will delve into Wittgenstein’s unique perspective on the nature of language and explore how his concept of language games can be used to conceptualize and heal psychological trauma. Additionally, we will examine Wittgenstein’s views on the limitations of psychology as a discipline and his belief that his theories would not be fully understood during his lifetime.

Understanding Wittgenstein’s Language Games Central to Wittgenstein’s later philosophy is the concept of language games, which he introduced in “Philosophical Investigations.” Language games refer to the diverse ways in which language is used in different contexts and situations, each with its own set of rules and meanings. Wittgenstein argued that language is not a rigid, formal logic with universally applicable rules, but rather a dynamic, social construction that evolves through use and interaction. The meaning of words and phrases is derived from the specific context in which they are used, and this meaning can shift depending on the “game” being played.

Wittgenstein’s understanding of language games represents a significant departure from his earlier work, the “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus,” in which he attempted to define the limits of language and the world. In “Philosophical Investigations,” he acknowledges the limitations of this approach, recognizing that language is far more complex and multifaceted than any formal system can capture. By focusing on the practical, everyday use of language, Wittgenstein opens up new possibilities for understanding the relationship between language, meaning, and human experience.

Applying Language Games to Psychological Trauma

Psychological trauma is a deeply personal and complex experience that can be challenging to articulate and understand. Wittgenstein’s language games provide a powerful framework for conceptualizing trauma and its impact on an individual’s life. By recognizing that the language used to describe traumatic experiences is part of a unique “game,” psychotherapists can gain a deeper understanding of their clients’ struggles and help them develop new ways of expressing and processing their emotions.

Example 1: Reframing Trauma Narratives One way psychotherapists can apply Wittgenstein’s ideas is by helping clients reframe their trauma narratives. Individuals who have experienced trauma often become trapped in a language game that perpetuates feelings of helplessness, guilt, or shame. These narratives can be deeply entrenched, making it difficult for clients to see alternative perspectives or find hope for healing. By working with clients to identify and challenge these limiting narratives, therapists can help them create new language games that promote resilience, self-compassion, and empowerment.

For instance, a client who has experienced sexual assault may have internalized a narrative that blames themselves for the attack. This self-blaming language is often reinforced by societal messages that place responsibility on the victim rather than the perpetrator. A therapist using Wittgenstein’s approach might help the client recognize that this narrative is part of a larger, harmful “game” that does not accurately reflect their experience. By questioning this narrative and developing a new language game that emphasizes the client’s strength, courage, and inherent worth, the therapist can support the client’s healing process and help them reclaim their sense of self.

Example 2: Embracing the Ineffable Wittgenstein also recognized that some experiences, particularly those related to emotions and inner states, are difficult or impossible to express through language. He referred to this as the problem of “private language” and argued that true understanding requires a shared social context. This insight has significant implications for psychotherapy, as it suggests that some aspects of traumatic experience may always remain beyond the reach of language.

Psychotherapists can use this understanding to help clients embrace the ineffable aspects of their traumatic experiences, rather than feeling pressured to put everything into words. By creating a safe, non-judgmental space for clients to explore their emotions through non-verbal means, such as art, music, or movement, therapists can support clients in processing their trauma in a way that feels authentic and meaningful to them.

For example, a therapist working with a client who has experienced a traumatic loss might encourage the client to engage in expressive arts therapy, such as painting or sculpting, to explore their grief. By allowing the client to express their emotions through a medium that does not rely on language, the therapist can help the client access and process feelings that may be too painful or complex to put into words. This approach recognizes the limitations of language in capturing the full depth of human experience and honors the client’s unique way of making meaning from their trauma.

Example 3: Building Shared Meaning Wittgenstein’s emphasis on the social nature of language highlights the importance of building shared meaning in the therapeutic relationship. By engaging in a collaborative process of exploring and defining the language games surrounding the client’s trauma, therapist and client can develop a deeper understanding of the client’s experiences and work together towards healing.

This process of building shared meaning involves a willingness on the part of the therapist to enter into the client’s language game, to listen deeply and ask questions that help clarify the client’s unique perspective. By taking the time to understand the specific words, phrases, and metaphors the client uses to describe their experiences, the therapist can demonstrate empathy, validation, and a genuine desire to understand the client’s world.

For instance, a therapist working with a client who has experienced childhood abuse might notice that the client frequently uses the phrase “feeling trapped” to describe their emotional state. Rather than assuming a shared understanding of this phrase, the therapist might ask the client to elaborate on what “feeling trapped” means to them. By exploring the specific images, sensations, and memories associated with this phrase, the therapist can gain a more nuanced understanding of the client’s experience and help them develop language that accurately reflects their reality.

This collaborative process of building shared meaning can also help clients feel more seen, heard, and understood in the therapeutic relationship. By demonstrating a willingness to enter into the client’s language game, the therapist can foster a sense of trust, safety, and connection that is essential for healing from trauma.

The Limitations of Psychology as a Discipline

In addition to his revolutionary ideas about language, Wittgenstein also expressed skepticism about the ability of psychology, as a discipline, to fully capture the complexities of human experience. He argued that much of what constitutes our inner lives and emotional states is “imponderable evidence” that cannot be easily studied or quantified using scientific methods.

Wittgenstein believed that the subjective, contextual nature of human experience made it difficult, if not impossible, to develop a systematic, rule-based approach to understanding the mind. He criticized attempts to reduce human behavior and cognition to simple, measurable units, arguing that such approaches failed to account for the rich, nuanced, and often contradictory nature of our mental lives.

This critique has important implications for psychotherapy, as it suggests that therapists must be cautious about relying too heavily on diagnostic categories, standardized assessments, or one-size-fits-all treatment approaches. While these tools can be useful in certain contexts, Wittgenstein’s philosophy reminds us that the most meaningful insights often come from a deep, empathetic engagement with the client’s unique experience, rather than from the application of abstract theories or techniques.

Wittgenstein’s Views on the Reception of His Ideas

Wittgenstein was keenly aware that his unconventional ideas about language, meaning, and psychology were unlikely to be fully understood or appreciated during his lifetime. He once remarked, “I am not sure I should like my writing to spare other people the trouble of thinking. But if possible, to stimulate someone to thoughts of his own.”

This comment reflects Wittgenstein’s belief that his role as a philosopher was not to provide definitive answers or explanations, but rather to provoke deeper reflection and questioning. He recognized that his ideas were challenging and often counterintuitive, and that it would take time for others to fully grasp their implications.

In many ways, Wittgenstein’s prediction about the reception of his ideas has proven accurate. While his work has had a profound impact on philosophy, psychology, and other fields, it is still often misunderstood or oversimplified. Many scholars continue to grapple with the complexities of his thought, and there remains much debate about how to interpret and apply his ideas in practice.

For psychotherapists, this suggests that engaging with Wittgenstein’s philosophy requires a willingness to sit with uncertainty, to question one’s assumptions, and to remain open to new possibilities for understanding and healing. It also highlights the importance of ongoing reflection, dialogue, and collaboration within the therapeutic community, as we work to integrate Wittgenstein’s insights into our evolving understanding of trauma, language, and the human experience.

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s later philosophy, particularly his concept of language games, offers a transformative approach to conceptualizing and healing psychological trauma. By recognizing the diverse, contextual nature of language and meaning, psychotherapists can help clients reframe limiting narratives, embrace the ineffable aspects of their experience, and build shared understanding in the therapeutic relationship.

Wittgenstein’s critique of psychology as a discipline also serves as an important reminder of the limitations of reductionist, rule-based approaches to understanding the human mind. As therapists, we must remain attuned to the unique, subjective nature of each client’s experience and be willing to engage in a collaborative process of exploration and meaning-making.

Although Wittgenstein recognized that his ideas would not be fully understood in his lifetime, his legacy continues to inspire and challenge us to think deeply about the nature of language, meaning, and the human experience. By engaging with his philosophy in a spirit of openness, curiosity, and empathy, we can continue to develop new and innovative approaches to healing the wounds of trauma and supporting our clients on their journey towards wholeness and resilience.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Citations

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Drury, M. O’C. (1973). The Danger of Words and Writings on Wittgenstein. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Grayling, A. C. (1996). Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heaton, J. M. (2010). The Talking Cure: Wittgenstein’s Therapeutic Method for Psychotherapy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Monk, R. (1990). Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Sluga, H. D. (2011). Wittgenstein. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bibliography

- Bouwsma, O. K. (1986). Wittgenstein: Conversations, 1949-1951. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Day, W. (2017). The Aesthetics of the Ordinary in Wittgenstein’s Later Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Drury, M. O’C. (1973). The Danger of Words and Writings on Wittgenstein. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Grayling, A. C. (1996). Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hacker, P. M. S. (1986). Insight and Illusion: Themes in the Philosophy of Wittgenstein. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Heaton, J. M. (2010). The Talking Cure: Wittgenstein’s Therapeutic Method for Psychotherapy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Klagge, J. C. (2001). Wittgenstein: Biography and Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Malcolm, N. (1958). Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir. London: Oxford University Press.

- McGinn, M. (2006). Elucidating the Tractatus: Wittgenstein’s Early Philosophy of Language and Logic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Monk, R. (1990). Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Moyal-Sharrock, D., & Brenner, W. H. (Eds.). (2007). Readings of Wittgenstein’s On Certainty. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rhees, R. (Ed.). (1984). Recollections of Wittgenstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sluga, H. D. (2011). Wittgenstein. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Stern, D. G. (2004). Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1961). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1969). On Certainty. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1980). Culture and Value. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1998). Notebooks, 1914-1916. Oxford: Blackwell.

0 Comments