Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4

Harnessing the Power of Jungian Archetypes in Psychotherapy: A Practical Guide for Patients and Therapists

Read More on Jung here:

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- Jungian archetypes are universal patterns from the collective unconscious that shape human experience.

- Archetypes can be used in psychotherapy to enhance self-awareness, reframe challenges, and facilitate dialogue with the unconscious.

- The Shadow archetype represents repressed aspects of the self that need integration for psychological wholeness.

- Individuation is the lifelong process of becoming one’s authentic self by integrating conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche.

- The animus (in women) and anima (in men) represent unconscious masculine and feminine elements that seek balance and integration.

- The Puer/Puella Aeternus archetype embodies eternal youth and potential, which can be both a source of renewal and a hindrance to maturity.

- Therapy can serve as an initiation process, guiding clients to differentiate from parental complexes and embrace adult responsibilities.

- Marion Woodman focused on embodying the feminine and confronting shadow aspects of the Puella archetype.

- Robert Moore emphasized integrating Puer energy into mature masculine archetypes for psychological wholeness.

- Working with archetypes can contribute to both individual healing and broader cultural transformation.

Understanding the Archetypes

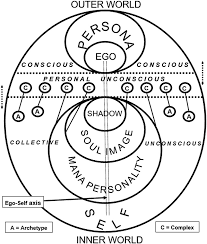

One of the most well-known and influential aspects of Jungian psychology is the concept of archetypes. For Jung, archetypes are universal patterns or motifs that arise from the collective unconscious and shape human behavior, experiences, and imagination. They are not specific images or symbols, but rather organizing principles that give rise to recurring themes across cultures and throughout history.

Jung identified numerous archetypes in his work, but some of the most prominent and clinically relevant include:

Archetypes in the Therapeutic Process

So how can Jungian archetypes be practically applied in psychotherapy? Here are a few key ways:

Enhancing Self-Awareness:

One of the primary goals of therapy is to help patients develop a deeper understanding of themselves – their patterns, their motivations, their strengths and weaknesses. By introducing the concept of archetypes and helping patients identify which ones are most active in their own psyche, therapists can facilitate a profound process of self-discovery. This enhanced self-awareness is the foundation for real change and growth.

Reframing Challenges:

Every person faces challenges and obstacles in life, whether external or internal. Jungian archetypes can provide a powerful framework for reframing these challenges in a more meaningful and empowering way. For example, a patient struggling with addiction might be encouraged to see their journey through the lens of the Hero’s quest – a difficult but ultimately transformative odyssey towards wholeness and self-mastery.

Facilitating Dialogue with the Unconscious:

Jung believed that the unconscious mind was not just a repository of repressed material, but a dynamic, creative force with its own wisdom and intelligence. By working with archetypes, therapists can help patients establish a dialogue with their unconscious, accessing new insights, ideas, and solutions. Techniques like active imagination, dream analysis, and creative expression can be particularly powerful in this regard.

Integrating the Shadow:

One of the most important Jungian archetypes is the Shadow – the repressed, denied, or unconscious aspects of the self. Often, these shadow elements are the source of much psychological distress and dysfunction. By helping patients confront and integrate their shadow, therapists can facilitate a process of deep healing and wholeness. This might involve exploring early childhood wounds, challenging self-limiting beliefs, or expressing long-suppressed emotions in a safe and supportive environment.

Cultivating Individuation:

Ultimately, the goal of Jungian therapy is individuation – the lifelong process of becoming more fully and authentically oneself. This involves integrating the conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche, balancing the archetypes, and developing a strong, centered sense of self. By using archetypes as a roadmap for this journey, therapists can help patients navigate the challenges and opportunities of personal growth with greater clarity, purpose, and resilience.

The Shadow and Golden Shadow: Embracing the Full Spectrum of the Psyche

The shadow is a fundamental concept in Jungian psychology, representing the unconscious aspects of the personality that an individual has rejected, repressed, or denied. These qualities, impulses, and desires are often experienced as dark, shameful, or inferior, as they are incompatible with the person’s chosen conscious attitude and self-image. The shadow is not inherently negative, but rather a natural part of the human psyche that contains both positive and negative potentials.

The formation of the shadow typically begins in childhood, as we learn to adapt to the expectations and norms of our family and society. In order to fit in and be accepted, we may suppress or disown certain parts of ourselves that are deemed unacceptable or undesirable. For instance, a child who is repeatedly told that anger is bad may learn to repress their own aggressive impulses, relegating them to the shadow. Over time, these repressed qualities accumulate in the unconscious, forming a hidden aspect of the personality that can exert a powerful influence on thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

While the shadow is often associated with negative qualities such as anger, jealousy, or greed, Jung emphasized that it also contains positive potentials that have been undeveloped or disowned. This “golden shadow” represents our untapped gifts, talents, and capacities that lie dormant, waiting to be integrated into conscious awareness. For example, an individual who has always prioritized logical thinking and rationality may have repressed their creative and intuitive side, which holds the key to unlocking new forms of self-expression and fulfillment.

Integrating the shadow is a crucial task in the process of individuation, which is the journey towards wholeness and self-realization. It involves acknowledging and accepting the parts of ourselves we have rejected, bringing the unconscious into conscious awareness. This process can be challenging, as it requires confronting our deepest fears, shames, and traumas, and taking responsibility for the aspects of ourselves we may prefer to keep hidden.

However, engaging in shadow work is ultimately liberating and transformative. By reclaiming our disowned selves, we free up the energy that was previously used to repress and deny them, allowing for greater vitality, authenticity, and wholeness. Integrating the shadow also enables us to develop greater empathy and understanding for others, as we recognize that everyone carries their own hidden depths and complexities.

In therapy, working with the shadow may involve a variety of techniques and approaches. Journaling and dream analysis can provide valuable insights into the unconscious mind, revealing the hidden desires, fears, and conflicts that shape our experience. Art therapy and other creative interventions can help clients express and explore the shadow in a safe, non-verbal way, bypassing the defenses of the conscious mind.

Role-playing and guided imagery can also be powerful tools for shadow integration, allowing clients to embody and engage with different aspects of their personality in a controlled setting. By providing a non-judgmental, supportive space for this exploration, therapists can help clients develop greater self-awareness, self-acceptance, and the capacity to embrace the full spectrum of their being.

As individuals do the work of shadow integration, they may also begin to uncover the golden shadow – the positive qualities and potentials that have been neglected or undeveloped. This can be a profound and exciting discovery, as it opens up new possibilities for growth, creativity, and self-actualization. A person who has always been shy and withdrawn may tap into a hidden reservoir of charisma and leadership ability, while someone who has been stuck in a unfulfilling career may rediscover a long-forgotten passion or talent.

Archetypes in Spirituality and Personal Growth

Beyond clinical practice, engaging with archetypes can be a powerful tool for personal growth and spiritual development. Many spiritual traditions use archetypal symbols and stories to map the journey of the soul, from the initial call to adventure to the final return home with newfound gifts and wisdom.

The hero’s journey, as described by Joseph Campbell, is a prime example of an archetypal pattern found across cultures and throughout history. It begins with the hero’s departure from the ordinary world, followed by a series of trials and challenges that test their courage and resolve. Along the way, the hero may encounter mentors, allies and enemies that embody different archetypal qualities. Ultimately, the hero must face their deepest fear or confront their greatest challenge, emerging transformed and victorious.

For individuals on a path of personal growth, understanding these archetypal patterns can provide a sense of meaning and purpose, even in the midst of suffering and confusion. By recognizing the universal human experiences embedded in myths and stories, we feel less alone and more connected to something larger than ourselves. We may begin to see our own struggles and triumphs as part of a greater unfolding, a timeless drama of the soul.

Depth psychologist Bill Plotkin, in his book Soulcraft, outlines a nature-based map of the psyche based on archetypes found in the natural world. He describes how connecting with the wisdom of the North (The Healer), South (The Warrior), West (The Visionary) and East (The Teacher) can guide us in reclaiming our wholeness and authenticity. Through wilderness rites of passage, dreamwork, council circles and other earth-honoring practices, Plotkin invites individuals to embark on a journey of “soul initiation,” descending to the underworld of the psyche in order to return with sacred gifts for their people and the planet.

Whether through clinical practice, personal growth or spiritual exploration, engaging with archetypes offers a profound path of self-discovery and transformation. By connecting with these timeless patterns, we open ourselves to the wisdom of the ages, the perennial truths that guide us home to our deepest nature. As therapists, healers and seekers, we have the privilege of midwifing this process, supporting others and ourselves in the eternal journey of becoming more fully human.

Archetypes in Action: How Three Theorists Applied Jungian Ideas to Transform Culture and Society

Since Jung’s death in 1961, his ideas have continued to evolve and inspire a wide range of thinkers, practitioners, and activists around the world. Today, Jungian psychology is a diverse and dynamic field, with a growing recognition of the need to engage with issues of social justice, cultural diversity, and ecological sustainability.

One of the key developments in contemporary Jungian thought has been the emergence of post-Jungian perspectives, which seek to critique and expand upon Jung’s original ideas in light of new insights from fields such as neuroscience, complexity theory, and postmodern philosophy. These approaches challenge some of the more essentialist and universalizing aspects of Jung’s thought, and emphasize the need for a more contextual and culturally-sensitive understanding of the psyche (Samuels, 1985).

David Tacey: Archetypes as a Bridge Between Sacred and Secular

Australian scholar David Tacey is known for his work on the intersection of Jungian psychology, spirituality, and contemporary culture. In books like The Spirituality Revolution (2004) and How to Read Jung (2006), Tacey argues that archetypes are not just psychological concepts but also spiritual realities that connect us to the numinous dimensions of existence. For Tacey, engaging with archetypes is a way of bridging the gap between the sacred and the secular, the ancient and the modern, the personal and the collective.

One of Tacey’s key insights is that archetypes often emerge in secular contexts where they are not recognized as such. In popular culture, for example, he sees archetypal themes and motifs constantly at play – in movies, music, advertising, and social media. By learning to decode these archetypal messages, Tacey believes we can tap into the deeper spiritual yearnings and possibilities of our time, even in the midst of a culture that often seems superficial or fragmented.

Tacey has also applied archetypal perspectives to social and political issues. In Edge of the Sacred (1995), he explores how the archetypes of masculine and feminine, light and shadow, play out in the gender politics and ecological crises of our time. He argues that by confronting and integrating these polarities within ourselves and our culture, we can move towards greater wholeness, balance, and sustainability.

For Tacey, working with archetypes is ultimately about cultivating a more conscious, authentic, and socially engaged spirituality. By connecting with these timeless patterns, we can find the resources we need to navigate the challenges of our personal and collective lives with greater wisdom, creativity, and compassion.

Robert Moore: Archetypes as Initiatory Guides

American psychologist Robert Moore, co-author of the influential book King, Warrior, Magician, Lover (1990), conceived of archetypes as inner guides or mentors that shape our development as individuals and as societies. Drawing on Jungian theory as well as indigenous and mythological traditions, Moore mapped out four key archetypes of mature masculinity – the King, Warrior, Magician, and Lover – each of which represents a crucial aspect of psychosocial development.

For Moore, these archetypes are not just abstract concepts but living presences that can be engaged with through ritual, imagination, and embodied practice. When we align ourselves with the positive, generative aspects of these patterns (the “King energy” of just leadership, the “Warrior energy” of focused discipline, etc.), we access greater resources for personal growth and social transformation. But when we fall into the shadow or immature dimensions of these same archetypes (the “Tyrant King,” the “Sadist Warrior,” etc.), we perpetuate cycles of violence, oppression, and self-destruction.

Moore applied this archetypal framework to a wide range of cultural and political issues. He argued that many of the crises facing modern society – from addiction and abuse to war and environmental degradation – stem from a failure to initiate young people (especially young men) into the mature forms of these essential roles. In the absence of such initiation, Moore believed, we remain stuck in the “boy psychology” of the immature archetypes, acting out our unintegrated shadows in destructive ways.

The solution, for Moore, was not to reject or suppress the archetypes, but to engage with them more consciously and creatively. He developed a variety of practices and programs (such as the “New Warrior Training Adventure”) designed to guide individuals through the initiatory process of confronting their shadows, claiming their unique gifts, and stepping into mature archetypal roles. By doing this inner work, Moore believed we could become more effective agents of positive change in the world, leading with the wisdom of the King, fighting with the discipline of the Warrior, and creating with the passion of the Lover.

James Hillman: Archetypes as the “Poetic Basis of Mind”

James Hillman, the founder of archetypal psychology, took Jung’s ideas in a more radical and imaginative direction. For Hillman, archetypes were not just psychological or spiritual concepts, but the very “gods” of the psyche – autonomous, animating forces that shape our perceptions, emotions, and behaviors. In works like Re-Visioning Psychology (1975) and The Dream and the Underworld (1979), Hillman argued that the task of psychology was not to interpret or explain these archetypal forces, but to engage with them aesthetically and poetically, honoring their irreducible mystery.

Like Tacey and Moore, Hillman saw archetypes at work not just in individual psyches but in the larger culture as well. He was particularly interested in how archetypal patterns play out in art, literature, and politics. For example, in his book The Soul’s Code (1996), Hillman explores the “acorn theory” of the self – the idea that each individual is born with a unique calling or destiny, shaped by a guiding archetype. By examining the lives of historical figures like Ella Fitzgerald and Adolf Hitler, Hillman shows how the archetypes of the “Jazz Singer” and the “Fuhrer” can manifest in radically different ways, for good or for ill.

Hillman was also a pioneer in applying archetypal ideas to social and environmental issues. In essays like “The Thought of the Heart” (1981), he critiques the modern Western worldview of the disenchanted, mechanical universe, arguing for a re-ensouling of our relationship to nature and the world. For Hillman, this meant recognizing the archetypal dimensions of ecological phenomena – seeing rivers and forests not just as resources to be exploited, but as living presences with their own intrinsic value and meaning.

Perhaps most provocatively, Hillman applied archetypal thinking to the problem of trauma and victimization. In The Soul’s Code and other works, he challenged the prevailing therapeutic model of excavating and processing childhood wounds, arguing that this approach often reinforces a sense of victimhood and dependence. Instead, Hillman advocated for a more mythic and imaginative engagement with trauma, one that recognizes the archetypal dimensions of even the most painful experiences. By “deliteralizing” our personal narratives and connecting them to larger archetypal patterns, Hillman believed we could find new resources for resilience, creativity, and meaning-making in the face of suffering.

Understanding the Eros and Logos Principles

Before diving into the specifics of working with animus and anima in therapy, it’s essential to grasp the underlying principles they represent. The animus, as the unconscious masculine element in women, is an expression of the Logos – the principle of reason, order, and directed action. The anima, as the unconscious feminine element in men, embodies the Eros – the principle of relationality, receptivity, and emotional depth.

In the psyche of each individual, these principles seek balance and integration. When one dominates at the expense of the other, psychological disequilibrium results. The woman identified with traditional femininity may struggle to find her own voice and direction in life, while the man disconnected from his emotions may find his relationships and creative pursuits feel hollow and devoid of meaning.

As therapists, our role is to help clients navigate the dance between Eros and Logos, finding an authentic expression of each that enhances rather than hinders their growth and well-being. This process involves both inner work – engaging the animus and anima directly – and outer work – developing more conscious, balanced ways of relating in the world.

Working with the Animus in Women

For women, the key to liberating the positive potential of the animus often lies in challenging the internalized voices of judgment, criticism, and “should” that limit their sense of possibility. Therapists can support this process in several ways:

Personifying the Animus:

Encourage your female clients to imagine the animus as a distinct personality, with his own characteristics, opinions, and agendas. This can be done through dialogue, active imagination, or even by drawing or sculpting an image of the figure. By personifying the animus, women gain distance from his influence and can begin to question his previously unexamined assumptions.

Tracking Animus Opinions:

Help clients notice when animus opinions are shaping their thoughts, decisions, and emotional reactions. These often show up as sweeping generalizations, black-and-white judgments, or harsh self-criticism. By catching these opinions in the act, women can begin to dis-identify from them and consider more nuanced perspectives.

Embracing Feminine Values:

Support women in valuing and prioritizing the feminine principles of relatedness, receptivity, and emotional attunement. This may involve exploring the ways they’ve neglected or devalued these qualities in themselves, as well as finding practical ways to express them more fully in work, relationships, and creative pursuits.

Developing Authentic Logos:

Challenge women to develop their own powers of discernment, critical thinking, and decisive action in service of their true values and goals. This may involve taking risks, setting boundaries, and learning to trust their own voice over the internalized expectations of others.

Working with the Anima in Men

For men, connecting with the positive potential of the anima often requires a descent into the emotional depths they’ve long avoided. Some ways therapists can facilitate this process include:

Exploring Emotional Nuances:

Help male clients develop a more sophisticated vocabulary for their feeling states, moving beyond the broad categories of “good” and “bad” to appreciate more subtle textures and flavors of emotion. This can be done through mindfulness practices, art therapy, or simply by slowing down and attending to the body’s signals.

Befriending the Anima:

Encourage men to approach the anima as an honored guest rather than an enemy to be conquered. This may involve dialoguing with her through active imagination, creating art or music that expresses her qualities, or simply cultivating an attitude of respectful curiosity toward the feeling dimensions of life.

Prioritizing Relationships:

Challenge men to value and nurture their personal relationships, viewing them not as distractions from their “real work” but as essential contexts for growth and meaning. This may require learning new relational skills, such as active listening, empathy, and vulnerability.

Embracing Creative Play:

Help men reconnect with the joy, spontaneity, and wonder of the imagination. This can be through engagement with art, music, dance, or any activity that enlivens their sense of possibility and deepens their appreciation for the non-linear dimensions of life.

Animus and Anima in the Therapeutic Relationship

Beyond these targeted interventions, the therapeutic relationship itself offers a powerful container for animus and anima integration. As therapists, we have the opportunity to model a grounded, embodied balance of masculine and feminine qualities – blending clear boundaries and direction with empathetic attunement and receptivity.

We can also use our own countertransference reactions to track how the client’s animus or anima may be constellated in the therapy process. A female client’s animus may manifest as a stubborn resistance to change, triggering the therapist’s own impatience or frustration. A male client’s anima may show up as a seductive pull toward rescuing or coddling, inviting the therapist to abandon their professional role.

By staying mindful of these dynamics and using them as grist for the therapy process, we create opportunities for clients to experience more conscious, flexible ways of relating. As they internalize a therapeutic relationship that honors both Logos and Eros, clients develop a template for more integrated and authentic expression of these principles in their lives beyond therapy.

Embracing the Puer and Puella Aeternus: A Jungian Path to Renewal and Meaning

Few archetypes have captured the imagination as vividly as the Puer and Puella Aeternus – the eternal youth, forever on the cusp of adulthood, brimming with potential yet afraid to fully embrace life’s challenges. Often viewed through a lens of pathology or immaturity, the Puer/Puella is typically seen as a problem to be solved, a complex to be overcome. But what if this eternal youth also holds the key to profound renewal, creativity, and meaning? In this blog post, we’ll explore the invaluable mission of the Puer and Puella Aeternus, and how therapists can help these individuals harness their unique gifts for personal and collective transformation.

The Puer/Puella and the Parental Complex To understand the Puer/Puella, we must first examine their relationship to the parental complex. According to Jung, the mother and father archetypes are two of the most powerful forces shaping the psyche. The mother represents the realm of the unconscious, of emotion, instinct, and the capacity for nurturing and renewal. The father, in contrast, embodies the principles of order, authority, responsibility and engagement with the external world.

For the Puer/Puella, these parental forces often remain entangled in complex, unconscious ways. They may struggle to differentiate their own identity and desires from the expectations and values of their parents, leading to a provisional, half-lived existence. The Puer may flit from job to job, relationship to relationship, never fully committing to any path. The Puella may retreat into fantasies of rescue or romanticized suffering, avoiding the challenges of authentic intimacy and self-responsibility.

At the core of this struggle is a fear of leaving the enchanted garden of childhood behind, of relinquishing the illusion of boundless potential for the hard work of actualizing one’s unique destiny. Yet it is precisely this capacity for bridging the realms of potential and manifestation that holds the key to the Puer/Puella’s invaluable mission.

The Puer/Puella as Bringer of Renewal In the words of Marie-Louise von Franz, the great Jungian scholar who devoted much of her work to the Puer Aeternus, “The puer’s main task in life is to bring renewal.” The Puer/Puella carries within them the spark of divine creativity, the capacity to envision new possibilities and challenge outdated modes of being. In a world that often feels stagnant, oppressive, or devoid of meaning, the Puer/Puella’s restless yearning for something more can be a catalyst for profound change.

We see this renewing energy at work whenever the Puer/Puella questions the status quo, rebels against unjust authority, or envisions alternative ways of living and relating. The Puer may be drawn to activist causes, seeking to dismantle oppressive systems and build a more just world. The Puella may channel her passion into art, music, or spirituality, creating works of beauty that awaken others to the enchantment of life. In the consulting room, the Puer/Puella client may inspire the therapist with their hunger for transformation, their refusal to settle for a life half-lived.

Yet this potential for renewal can only be actualized when the Puer/Puella learns to ground their vision in the challenges and responsibilities of adult life. The task is not to eradicate the Puer/Puella spirit, but to integrate it, to find a way of preserving one’s connection to the eternal source while also embracing the tasks of the temporal world. This is where the role of the therapist becomes crucial.

Therapy as Initiation:

Guiding the Puer/Puella to Wholeness For therapists working with Puer/Puella clients, the key is to approach their journey as a form of initiation – a guided descent into the underworld of the unconscious, followed by a return to the world of responsibilities and relationships. This process involves several key stages:

- Differentiating from the Parental Complex: The therapist must help the Puer/Puella client to identify and challenge their unconscious identification with parental values, expectations, and complexes. This may involve exploring early childhood dynamics, naming internalized voices of criticism or idealization, and empowering the client to begin authoring their own life narrative.

- Embracing the Shadow: The Puer/Puella must also confront the shadow aspects of their archetype – the ways in which their fear of commitment, responsibility, and limitation have held them back from fully engaging with life. This often evokes a period of disillusionment, grief, and rage as the client wrestles with the gap between their ideals and the constraints of reality. The therapist’s role is to provide a safe, nonjudgmental space for this process, while also challenging the client to take responsibility for their choices and actions.

- Discovering Purpose and Vocation: As the Puer/Puella begins to relinquish their provisional lifestyle and fantasy-driven approach to life, a deeper sense of meaning and purpose often emerges. The therapist can help the client to identify their authentic values, passions, and gifts, and to explore how these might be channeled into a vocation or calling. This may involve pursuing further education, developing new skills, or taking risks to actualize long-held dreams.

- Cultivating Meaningful Work and Relationships: Ultimately, the goal is to help the Puer/Puella client build a life of authentic engagement, one in which their capacity for creativity and vision is grounded in the responsibilities and joys of the everyday. This often involves learning new relational skills, such as the ability to tolerate conflict, communicate needs and boundaries, and navigate the challenges of intimacy. It also requires a willingness to commit to a path of meaningful work, whether that takes the form of paid employment, creative pursuits, activism, or service to others.

Throughout this journey, the therapist serves as a guide and mentor, modeling the possibility of living a life that bridges the realms of potential and manifestation, eternal youth and grounded wisdom. By helping the Puer/Puella to navigate the challenges of initiation, the therapist supports them in unleashing their unique gifts for the renewal and transformation of self and world.

Marion Woodman and Robert Moore: Puer/Puella and the Path of Initiation

Two influential Jungian thinkers who have explored the Puer and Puella archetypes in depth are Marion Woodman and Robert Moore. While their approaches differ in some respects, both recognize the powerful role these archetypes play not only in individual development but in shaping the larger patterns of culture and society. Central to their understanding is the idea of initiation – the necessary but often painful process of moving from the enchanted garden of eternal youth into the challenges and responsibilities of mature adulthood.

Marion Woodman: Embodying the Feminine

Marion Woodman, a pioneering Jungian analyst and author, is known for her groundbreaking work on feminine psychology and the body. In books like Addiction to Perfection (1982) and The Ravaged Bridegroom (1990), Woodman explores how the Puella archetype often manifests in women as a kind of disembodied perfectionism, a flight from the earthly realities of the feminine into a realm of ethereal fantasy and control.

For Woodman, the Puella represents a woman’s disconnection from her own instinctual nature, her deep feelings and desires, her cyclical and embodied way of being in the world. This disconnection is often reinforced by a culture that idealizes a kind of abstract, disembodied femininity, while devaluing or even demonizing the actual lived experience of women’s bodies and emotions.

The result, Woodman argues, is a epidemic of eating disorders, addictions, and other self-destructive behaviors among women. The Puella, terrified of the messiness and vulnerability of real human relationships, seeks refuge in a kind of sterilized, idealized world where she can maintain the illusion of purity and control. But this flight from the body and the feminine always exacts a terrible price, leading to a sense of emptiness, despair, and a profound alienation from one’s own soul.

The path of initiation for the Puella, in Woodman’s view, involves a painful but necessary descent into the dark, neglected regions of the psyche. It requires a willingness to confront the shadow aspects of the feminine – the rage, grief, and wild hungers that have been denied and repressed. Only by embodying these rejected parts of herself can the Puella begin to discover her true identity and power, rooted not in fantasy and perfection but in the raw, transformative energies of the archetypal feminine.

For Woodman, this initiation often takes the form of a symbolic death and rebirth, a letting go of the old, false self in order to be reborn into a more authentic and embodied way of being. It requires a kind of sacred marriage between the light and dark aspects of the feminine, a willingness to embrace both the joy and the pain, the beauty and the terror of the fully lived feminine experience. Only then can the Puella begin to find her true voice, her deep purpose, and her place of belonging in the world.

Robert Moore: Initiating the Masculine

Robert Moore, a psychologist and co-author of the influential book King, Warrior, Magician, Lover (1990), also sees the Puer archetype as a central challenge in masculine development. For Moore, the Puer represents the boy who has not yet been initiated into the mature masculine, the hero who has not yet learned to channel his energy and passion in service of something greater than himself.

In contemporary culture, Moore argues, the Puer often takes the form of the “eternal boy” – the man-child who refuses to grow up, to commit to anything or anyone beyond his own pleasure and self-interest. This Puer energy can manifest as a kind of narcissistic entitlement, a reckless disregard for consequences, or a grandiose inflation that denies the realities of human limitation and vulnerability.

At the same time, Moore recognizes that the Puer also carries within him a vital spark of divine creativity, a connection to the transpersonal realms of myth and imagination. The challenge is not to eradicate the Puer spirit, but to initiate it, to help it grow up and take its rightful place in the larger ecology of the mature masculine psyche.

For Moore, this initiation requires a confrontation with the shadow aspects of the masculine – the repressed anger, sadness, and vulnerability that the Puer seeks to deny or escape. It involves a willingness to submit to the necessary disciplines and trials of the hero’s journey, to face one’s fears and limitations head-on, and to emerge tempered and transformed on the other side.

Ultimately, the goal is to integrate the Puer energy into the larger constellation of mature masculine archetypes – the King, Warrior, Magician, and Lover. Each of these archetypes represents a crucial aspect of masculine wholeness – the King’s capacity for just and generative leadership, the Warrior’s ability to set boundaries and fight for what matters, the Magician’s gift for deep knowing and transformation, and the Lover’s attunement to the realms of eros, sensuality, and relationship.

When these archetypes are not adequately cultivated and integrated, Moore argues, the result is a kind of “boy psychology” writ large – a culture of immaturity, irresponsibility, and arrested development. We see this immature masculine playing out in everything from corporate greed and political corruption to the epidemic of violence and sexual assault in our society.

The solution, for Moore, is not to reject or condemn the Puer, but to offer him a path of genuine initiation into the mature masculine. This path is not easy – it demands sacrifice, courage, and a willingness to let go of cherished illusions and defenses. But it is also a path of profound meaning and purpose, one that allows a man to discover his true strength, integrity, and capacity for generative service in the world.

Varied Perspectives

While their approaches differ in their specific focus and language, both Woodman and Moore recognize that the Puer and Puella archetypes are not just individual psychological patterns, but powerful forces shaping the larger culture in which we live. When these archetypes are not adequately recognized and initiated, the result is a kind of arrested development on a collective scale – a culture of narcissism, consumerism, and irresponsibility that threatens the very foundations of our social and ecological well-being.

The task of initiation is not easy, for individuals or for cultures. It demands a willingness to confront our shadows, to let go of cherished illusions and defenses, and to submit to the necessary trials and disciplines of growth. But it is also a path of profound meaning and purpose, one that allows us to discover our deepest identity and our highest calling in the world.

As therapists, our role is to support this process of initiation in our clients, to provide a safe and generative space for the confrontation with the shadow, the exploration of new possibilities, and the emergence of a more authentic and integrated self. By doing so, we not only facilitate individual healing and growth, but also contribute to the larger process of cultural transformation, helping to midwife a world that is more whole, more responsible, and more attuned to the deep mysteries of the soul.

Bibliography

- Jung, C.G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

- von Franz, M-L. (2000). The Problem of the Puer Aeternus. Inner City Books.

- Woodman, M. (1982). Addiction to Perfection. Inner City Books.

- Moore, R., & Gillette, D. (1990). King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine. HarperOne.

- Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

- Tacey, D. (2006). How to Read Jung. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Johnson, R.A. (1989). He: Understanding Masculine Psychology. Harper & Row.

- Johnson, R.A. (1989). She: Understanding Feminine Psychology. Harper & Row.

- Hollis, J. (1993). The Middle Passage: From Misery to Meaning in Midlife. Inner City Books.

- Stevens, A. (1994). Jung: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Bly, R. (1990). Iron John: A Book About Men. Addison-Wesley.

- Perera, S.B. (1981). Descent to the Goddess: A Way of Initiation for Women. Inner City Books.

- Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court.

- Sharp, D. (1991). Jung Lexicon: A Primer of Terms & Concepts. Inner City Books.

- Edinger, E.F. (1992). Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Shambhala.

0 Comments