Who is David Tacey?

David Tacey (1953-) is a prominent Australian scholar and thinker known for his unique contributions bridging analytical psychology, spirituality, and cultural studies. As a leading figure in post-Jungian thought, Tacey has built upon and extended many key ideas from the depth psychology tradition while innovatively applying them to analyze contemporary secular societies and the modern crisis of meaning.

Over his prolific career, Tacey has articulated a powerful interdisciplinary vision that foregrounds the sacred underpinnings of human experience and calls for a “spirituality revolution” to heal the soul of the modern world. Drawing upon the mythological and archetypal perspectives advanced by Jung and Neumann, Tacey offers a penetrating critique of the spiritual emptiness and ecological devastation wrought by modern materialism, rationalism, and the Enlightenment worldview. At the same time, he discerns in the rise of the New Age movement, the worldwide renaissance of indigenous religions, and the surge of interest in Eastern philosophies the signs of an inchoate spiritual awakening sweeping the globe.

This essay provides an in-depth exploration of Tacey’s thought and its significance for understanding the psycho-spiritual crisis of late modernity. It elucidates his key ideas regarding the resacralization of the secular, the emergence of a “new spirituality,” and the transformative potential of the current “return of the repressed” in religious and mythological guise. Additionally, it examines his creative innovations of Jungian and post-Jungian concepts and evaluates his contributions to the contemporary study of spirituality and culture. Finally, it offers a retrospective on Tacey’s scholarly legacy, assessing which of his proposals have proved most influential and generative while noting critiques of his approach.

Additional Resources on Tacey:

- Books: Edge of the Sacred Amazon

- YouTube Lecture: David Tacey on Spirituality

- Interview: In Conversation with David Tacey

- Podcast: Tacey on Jung and Spirituality

- Article: David Tacey on the Future of Religion

- Institute: David Tacey at Latrobe University

- Research: Tacey’s Publications

- Quotes: David Tacey Quotes

- Lecture Series: Tacey’s Jung Lectures

Main Ideas and Key Themes:

- Tacey analyzes the “spiritual malaise” of secular modernity as symptomatic of a pervasive loss of contact with the collective unconscious and the archetypal substratum of human experience.

- He argues that the rise of rationalism and the “modern enlightenment project” have disenchanted the world, repressing the spiritual impulse and exiling the sacred to the margins of Western societies.

- In response, Tacey discerns the emergence of a “new spirituality” that seeks to resacralize secular life by reconnecting individuals to the archetypal depths of the psyche and their communities to an ensouled, animate world.

- He sees the worldwide “return of the repressed” in religious, mythological, and indigenous guise as heralding a global “spirituality revolution” with the potential to heal both personal and planetary ills.

- Tacey emphasizes the importance of spirituality as a “third force” alongside science and religion, one uniquely capable of reconciling their competing truth claims while grounding a revivified public morality.

- Drawing on concepts from Jungian and post-Jungian depth psychology, he argues for the centrality of the sacred to psychological health and explores the archetypes of spiritual transformation.

- Tacey advances a notion of “ecospirituality” that sacralizes the natural world and recognizes humanity’s deep interconnection with the Earth, enjoining a renewed ethic of ecological stewardship.

- While affirming key tenets of the Jungian tradition, he moves beyond Jung in exploring the psychospiritual dynamics of groups, cultures, and historical eras in addition to those of the individual.

The Spirituality Revolution:

The heart of Tacey’s scholarly project is his discernment and championing of an incipient “spirituality revolution” emerging in the late modern world. Across a series of influential books — including The Spirituality Revolution (2004), The Darkening Spirit (2013), and Gods and Diseases (2011) — he has traced the contours of this “new spirituality” and articulated its potential to resacralize both individual and collective life.

For Tacey, the defining feature of this nascent revolution is the turn from exoteric religious forms towards a direct, unmediated encounter with the sacred as immanent in self, world, and cosmos. He argues that traditional religious institutions, mired in literalism and shackled to premodern metaphysics, have lost credibility for many in the secular West. In their wake, a variety of “spiritualities of life” have proliferated that seek the sacred not in some transcendent beyond but in the depths of the psyche and the living fabric of the Earth.

Tacey sees the “rise of the sacred feminine” in contemporary goddess spirituality, the worldwide renaissance of indigenous religions, the popularity of Buddhist mindfulness, and the surge of “spiritual but not religious” sentiment as core expressions of this revolution. While highly variegated, he suggests these phenomena share a common impulse to resacralize a world disenchanted by scientific materialism and to cultivate a more embodied, holistic, and ecologically-attuned way of being.

In Tacey’s analysis, this “new spirituality” is characterized by several key features:

Immanence:

It locates the sacred not in some otherworldly realm but in the depths of the psyche, the natural world, and the cosmos itself. The divine is understood as infusing all of reality rather than standing apart from it.

Experience:

It prioritizes direct, unmediated encounter with sacred presence over belief in doctrines or adherence to external authorities. Firsthand experience is the arbiter of spiritual truth.

Fluidity:

It is improvisational, eclectic, and provisional, drawing freely from multiple traditions to craft a personal spiritual path. It rejects fixed dogmas and institutions in favor of an evolutionary, open-ended approach.

Embodiment:

It embraces the body, sexuality, and sensuous life as vessels of sacred presence rather than repressing them as obstacles to spiritual growth. Physicality itself is recognized as holy.

Ecology:

It fosters an ethic of reverence for the Earth and all its creatures, recognizing the interconnectedness of self, society, and planetary life. “GreenSpirit” becomes central to its vision.

Liberation:

It seeks not to transcend the world but to transform it, linking spiritual awakening to the quest for social justice and the creation of a planetary culture of peace, sustainability, and human fulfillment.

For Tacey, these currents herald a “rising sacred” within secular modernity that promises to re-enchant the world and heal the dissociations of the modern psyche. By reconnecting individuals to the collective unconscious and grounding them in archetypal realities, the new spirituality fosters psychic wholeness and liberation from the constrictions of the ego. At the same time, by resacralizing the natural world and human social life, it provides a renewed moral compass and basis for cultural regeneration in an era of global crisis.

Tacey is careful to note the ambiguities and shadow sides of this emerging revolution. He cautions against the dangers of narcissistic self-absorption, escapist fantasies, and psychic inflation that can attend uncritical immersion in some New Age spiritualities. Likewise, he acknowledges the risk that the new spirituality’s suspicion of institutions and authorities may leave it ungrounded, diffuse, and incoherent.

Nevertheless, Tacey insists that the “return of the repressed” spiritual impulses carries within it the seeds of genuine transformation, both personal and collective. By tapping into the regenerative powers of the unconscious and reconnecting humanity to its ontological ground, the “rising sacred” in secular societies may spur creative solutions to the planetary crises that beset us. As such, he enjoins scholars and cultural leaders to engage the new spirituality as a serious force and to help midwife its evolution towards maturity.

The Resacralization of the Secular:

A central theme in Tacey’s work is the resacralization of secular life in the modern West. He argues that the Enlightenment project of disenchantment, while liberating in certain respects, has ultimately left individuals spiritually adrift and cut off from the deeper wellsprings of meaning. The rationalist worldview, in banishing the sacred to the margins of culture, has impoverished the human experience and spawned a host of psychic and social ills.

Tacey suggests that the rise of secularism was itself a necessary evolutionary step, allowing for the emergence of individual autonomy and the differentiation of cultural spheres. In pre-modern societies, religion permeated all aspects of life, fusing the spiritual and temporal in a seamless sacred canopy. With the advent of modernity, however, religion was displaced from its central role and relegated to a separate, privatized sphere. This “divorce” of religion from public life allowed for the flourishing of science, democracy, and human rights unencumbered by traditional dogmas.

Yet Tacey contends that this process of secularization has now overshot its mark. The complete expulsion of the sacred from culture has left a gaping void at the heart of modern societies. Bereft of any sense of ultimate meaning or transcendent purpose, individuals are cast adrift in a cosmos rendered cold and indifferent. The result is a pervasive “crisis of meaning” and a host of psychospiritual maladies, from alienation and anomie to addiction and despair.

In response, Tacey discerns the emergence of a countervailing trend towards resacralization in contemporary culture. Across a wide range of domains — from the arts and media to ecology and health — he sees a “rising sacred” infiltrating the secular and imbuing it with new spiritual significance. This resacralization is not a return to pre-modern religious forms but a creative re-appropriation of sacred symbols, myths, and practices in a postmodern context.

For example, Tacey points to the upsurge of interest in yoga, meditation, and other contemplative practices as evidence of a hunger for embodied spiritual experience in the midst of secular life. Likewise, he sees the proliferation of “mind-body-spirit” titles in popular culture as reflective of a grassroots turn towards holistic conceptions of health and well-being. Even in the realm of science, he suggests, cutting-edge work in fields like quantum physics and systems theory is challenging the mechanistic paradigm and pointing towards a re-enchanted, interconnected universe.

At the heart of this resacralization, for Tacey, is a shift from a dualistic to a non-dual worldview. Whereas the Enlightenment project was predicated on a sharp dichotomy between matter and spirit, humans and nature, the emerging “new spirituality” seeks to heal these rifts and restore a sense of deep interconnection. It acknowledges the sacred as immanent within the world rather than transcendent of it, and sees divinity as manifest in all aspects of life.

This non-dual perspective, Tacey argues, is essential for addressing the manifold crises facing the planet. By re-embedding individuals in a sacred cosmos and fostering a sense of reverence for all beings, it provides the motivational wellsprings for a renewed ethics of care and responsibility. And by bridging the split between science and religion, reason and faith, it opens up new possibilities for integrated solutions to complex global challenges.

Ultimately, for Tacey, the resacralization of the secular is about more than just individual spiritual fulfillment; it is a cultural and evolutionary imperative. In a world racked by social, economic, and ecological upheaval, the recovery of a sense of deep meaning and purpose is essential for navigating the storms ahead. Only by re-enchanting the world and rediscovering our profound interconnection with each other and the Earth can we hope to create a sustainable and flourishing future.

David Tacey’s Ecology and Indigenous Aboriginal Myth Studies:

One important area of Tacey’s research and writing that deserves more attention is his engagement with Australian and global ecology and indigenous Aboriginal myth studies. Tacey has consistently emphasized the importance of reconnecting with the natural world and the wisdom of indigenous cultures in order to address the spiritual and ecological crises of our time.

In his book Edge of the Sacred, Tacey explores how Aboriginal Australian cosmology and dreamtime stories can offer insights for re-enchanting our relationship with the Earth. He argues that the Aboriginal worldview, which sees the land as sacred and humans as deeply interconnected with all of life, challenges the dualistic and alienated consciousness of modernity. By listening to the myths and rituals of indigenous cultures, Tacey suggests, we can begin to recover a sense of the sacredness of nature and our place within the web of creation.

Tacey has also drawn on Aboriginal perspectives to critique the anthropocentrism and hubris of Western culture. He points out that in many indigenous societies, humans are seen as just one part of a larger living system, rather than as separate from and superior to the rest of nature. This ecological humility, he argues, is essential for addressing the environmental devastation wrought by modern industrial civilization.

In addition to his work on Aboriginal spirituality, Tacey has also engaged with other indigenous traditions from around the world. He has written about the resurgence of shamanism in the contemporary West, and how indigenous practices like vision quests and sweat lodges are being adopted by spiritual seekers as a way to reconnect with the sacred. While he acknowledges the dangers of cultural appropriation, Tacey suggests that a respectful and authentic engagement with indigenous wisdom can help to heal the split between humans and nature in modern societies.

Ultimately, for Tacey, the task of re-enchanting our relationship with the Earth is not just a matter of personal spirituality, but a collective imperative for our time. He argues that we need a new global mythology that honors the sacredness of nature and recognizes our profound interconnection with all of life. By drawing on the insights of indigenous cultures and contemporary ecology, Tacey believes we can begin to create a more sustainable and life-affirming civilization.

Unique Threads in Jung that Tacey Sees and Develops:

Another key contribution of Tacey’s work is his identification and development of unique threads in Jung’s thought that have often been overlooked or underemphasized by other scholars. In particular, Tacey highlights Jung’s prophetic vision of a coming “New Age” and his understanding of the role of the sacred in the post-secular world.

In his essay “The Darkening Spirit,” Tacey explores Jung’s prescient anticipation of the spiritual crisis of late modernity. As early as the 1930s, Jung warned that the rise of fascism and totalitarianism in Europe represented a dangerous compensation for the loss of spiritual meaning in the modern West. He saw the decline of traditional religion and the rise of secular materialism as leading to a “spiritual starvation” that left individuals vulnerable to the lure of charismatic leaders and mass movements.

At the same time, Jung also foresaw the emergence of a new kind of spirituality that would transcend the limitations of both traditional religion and secular rationalism. He spoke of a coming “New Age” in which individuals would seek direct experience of the sacred through a variety of non-orthodox paths. Jung saw this as a necessary evolution of human consciousness, as the old religious forms and symbols lost their power to contain and transform the energies of the psyche.

Tacey picks up on this thread in Jung’s work and argues that we are now living through the kind of spiritual transformation that Jung anticipated. He sees the rise of alternative spiritualities, the renewal of indigenous traditions, and the growing interest in mysticism and consciousness studies as signs of a “spirituality revolution” sweeping the globe. Tacey suggests that this revolution represents a paradigm shift in human culture, as we move from a secular worldview based on scientific materialism to a post-secular one that recognizes the sacred as a fundamental dimension of reality.

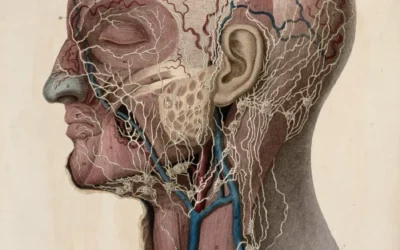

Another unique insight that Tacey draws from Jung is the idea of the “reality of the psyche.” For Jung, the psyche was not just a subjective inner world, but an objective reality that transcended the individual. He saw the archetypes of the collective unconscious as autonomous forces that shaped both personal and cultural life, and that connected humans to a larger spiritual reality.

Tacey builds on this idea to argue for a “metaphysical turn” in our understanding of the psyche. He suggests that the psyche is not just a product of brain chemistry or social conditioning, but a manifestation of a deeper reality that underlies and infuses the material world. Drawing on the work of scholars like Owen Barfield and Gregory Bateson, Tacey proposes an “ecological” view of the psyche that sees it as embedded in a living, sentient universe.

This perspective has important implications for how we understand the nature of spiritual experience and transformation. If the psyche is a gateway to a larger reality, then practices like dreamwork, active imagination, and shamanic journeying can be seen as ways of accessing and aligning with the intelligence of the cosmos. Tacey suggests that by cultivating a more porous and participatory relationship with the world, we can begin to heal the dissociation of modern consciousness and rediscover our deep belonging to the Earth community.

The Three Epochs of Jung’s Vision and the Post-Secular Sacred:

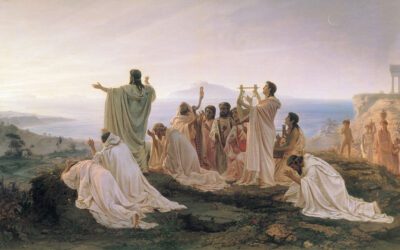

A central theme in Tacey’s interpretation of Jung is the idea of three great epochs or eras in the evolution of human consciousness. Drawing on Jung’s work, Tacey suggests that humanity has gone through three major stages in its relationship to the sacred, each with its own characteristic worldview and spiritual orientation.

The first epoch, which Jung called the “original all-oneness,” was characterized by a unified, mythic consciousness in which humans experienced themselves as embedded in a sacred cosmos. In this era, which corresponds to the worldview of indigenous and traditional societies, there was no sharp distinction between the natural and the supernatural, the physical and the spiritual. The world was experienced as alive and enchanted, and humans participated in the larger web of creation through ritual, myth, and shamanic practice.

The second epoch, which emerged with the rise of agriculture and civilization, saw the gradual differentiation of human consciousness from the matrix of nature. In this era, which reached its apex in the Axial Age and the birth of the great world religions, humans began to experience themselves as separate from the world and from the gods. The sacred was projected onto a transcendent realm beyond the earth, and religious institutions arose to mediate between the human and the divine.

The third epoch, which Jung saw as beginning in the modern era, is characterized by the complete desacralization of the world and the triumph of scientific materialism. In this “Godless” age, the sacred is reduced to a subjective, inner experience, and the earth is seen as a dead, mechanical object to be exploited for human gain. Jung saw this epoch as leading to a profound spiritual crisis, as individuals lost touch with the deeper sources of meaning and purpose that had sustained human life for millennia.

However, Jung also believed that this third epoch was not the end of the story. He foresaw the emergence of a new, post-secular age in which the sacred would be rediscovered in the depths of the psyche and the living fabric of the earth. In this new era, spirituality would no longer be the province of religious institutions, but a direct, experiential encounter with the numinous dimensions of reality.

Tacey picks up on this prophetic strand in Jung’s thought and argues that we are now witnessing the birth pangs of this new, post-secular epoch. He suggests that the “spirituality revolution” sweeping the world represents a collective awakening to the sacred that is no longer bound by traditional religious forms. Tacey sees evidence of this shift in the rise of ecological spirituality, the renewal of indigenous wisdom traditions, the popularity of meditation and yoga, and the growing interest in psychedelics and shamanism.

At the same time, Tacey emphasizes that this post-secular spirituality must not abandon the insights of reason and science, but rather integrate them into a more holistic and embodied way of knowing. He argues for a “grounded spirituality” that honors the material world as an expression of the sacred, and that seeks to heal the split between nature and culture, matter and spirit.

In this sense, Tacey sees Jung as a prophet of a new kind of “empirical mysticism” that bridges the divide between science and spirituality. Jung’s approach to the psyche as an empirical reality that can be studied and engaged with through direct experience offers a model for a post-secular spirituality that is both grounded and transcendent. By honoring the reality of the psyche and the living intelligence of the Earth, Tacey suggests, we can begin to create a new world that is both spiritually vibrant and ecologically sustainable.

David Tacey’s Methodology in Studying Jung’s Life and Work:

One of the distinguishing features of David Tacey’s scholarship is his unique approach to historical research and his methodology in studying Carl Jung’s life and work. Unlike many academic historians who prioritize a strict reliance on primary sources and a narrowly contextualized reading of texts, Tacey adopts a more interdisciplinary, interpretive, and even “imaginal” approach to engaging with Jung’s legacy.

At the heart of Tacey’s methodology is a commitment to what he calls “depth historiography.” This approach seeks to uncover the deeper psychological, spiritual, and archetypal dimensions of historical figures and movements, rather than simply chronicling surface-level events or ideas. Tacey is less interested in constructing a linear narrative of Jung’s life or a systematic exposition of his theories than he is in discerning the underlying “soul” or “spirit” that animates Jung’s work and continues to speak to the present moment.

To this end, Tacey draws on a wide range of sources beyond the traditional historical archive. In addition to Jung’s published writings and personal correspondence, he engages deeply with Jung’s Red Book, his artistic creations, his dreams and visions, and even the synchronicities and paranormal experiences that shaped his thought. Tacey sees these non-rational and symbolic dimensions of Jung’s life as essential keys to understanding his psycho-spiritual worldview and the prophetic nature of his message.

Moreover, Tacey approaches Jung not just as a historical figure to be studied but as a living presence whose ideas continue to evolve and transform in dialogue with the contemporary world. He reads Jung’s work not only in its original context but also in light of the spiritual and ecological crises of our time, discerning in it a “new revelation” for a secular age. In this sense, Tacey’s methodology is not just historical but also hermeneutical, seeking to interpret and apply Jung’s insights to the urgent questions and challenges of the present.

This approach is evident in Tacey’s book How to Read Jung (2006), where he introduces key Jungian concepts not as abstract theories but as dynamic, archetypal realities that shape both individual and collective experience. By exploring symbols like the “Self,” the “shadow,” the “anima/animus,” and the “God-image” in their mythic and experiential dimensions, Tacey seeks to evoke their transformative power and invite readers into a direct encounter with the sacred.

Central to Tacey’s methodology is a participatory and dialogical mode of engagement with Jung’s ideas. Rather than maintaining a strict scholarly distance or claiming an authoritative interpretation, Tacey enters into an active conversation with Jung, testing his concepts against his own experience and the realities of the contemporary world. He encourages readers to do the same, to “dream the dream onward” and to creatively adapt Jung’s insights to their own lives and contexts.

This approach is not without its critics, who may accuse Tacey of projecting his own agenda onto Jung or of neglecting the historical and cultural specificity of his thought. Some scholars have argued that Tacey’s “imaginal” reading of Jung risks conflating the psychological and the spiritual, or of elevating Jung to the status of a “prophet” rather than a thinker bound by his time and place.

However, Tacey is careful to acknowledge the limitations and shadow aspects of Jung’s work, as well as the need for a critical and discerning engagement with his ideas. He recognizes that Jung was a product of his cultural context and that some of his views, particularly around gender and race, are problematic from a contemporary perspective. At the same time, Tacey argues that the depth and universality of Jung’s insights transcend his individual limitations and continue to offer a vital resource for personal and collective transformation.

Tacey’s Empirical Mysticism and Reverence for Metaphor:

A key aspect of Tacey’s approach to spirituality is his commitment to an “empirical mysticism” that honors both the insights of science and the power of metaphor and symbol. Unlike some proponents of New Age spirituality who reject the material world as an illusion, Tacey insists on the reality and importance of the physical universe. At the same time, he argues that a purely literalistic and reductionistic approach to reality is inadequate for understanding the depths of human experience and the mysteries of the cosmos.

Tacey’s empirical mysticism seeks to bridge the divide between the objective and subjective dimensions of reality. He argues that the psyche is an empirical reality that can be studied and verified through direct experience, just like the physical world. However, he also suggests that the language of the psyche is not literal but symbolic, and that engaging with its depths requires a poetic and imaginative sensibility.

In this sense, Tacey sees Jung as a pioneer of a new kind of science that honors the power of metaphor and archetype. Jung’s approach to the psyche as a living, dynamic reality that communicates through dreams, visions, and synchronicities offers a model for a more participatory and enchanted relationship with the world. By engaging with the psyche on its own terms, Tacey suggests, we can begin to unlock its transformative potential and align ourselves with the deeper patterns of meaning that shape our lives.

At the same time, Tacey is careful to distinguish his empirical mysticism from a purely subjective or relativistic approach to spirituality. He argues that while the psyche speaks in the language of symbol and metaphor, its insights can be tested and verified through a rigorous process of inner exploration and outer dialogue. Tacey sees Jung’s method of amplification, in which the personal associations and cultural resonances of a symbol are explored in depth, as a model for this kind of empirical inquiry.

Moreover, Tacey emphasizes that an authentic spirituality must be grounded in a reverence for the Earth and a commitment to social and ecological justice. He argues that the task of our time is to create a new global mythology that honors the sacredness of nature and the interdependence of all life. This mythology must be rooted in the lived experience of individuals and communities, but it must also be responsive to the larger challenges facing our planet.

In this sense, Tacey’s empirical mysticism is not just a personal path of inner growth, but a collective project of cultural transformation. By recovering a sense of enchantment and reverence for the world, he suggests, we can begin to heal the wounds of modernity and create a more just and sustainable future. This requires a willingness to engage with the shadow side of our psyche and our society, and to confront the ways in which we have separated ourselves from the living Earth.

Ultimately, for Tacey, the goal of an empirical mysticism is not just to experience the sacred, but to embody it in the world. By aligning ourselves with the deeper patterns of meaning that shape the cosmos, we can become co-creators of a new reality that is both spiritually vibrant and ecologically sane. This requires a paradoxical embrace of both the rational and the mythic, the scientific and the symbolic, the material and the spiritual. Only by honoring the full complexity of the human experience, Tacey suggests, can we hope to navigate the challenges of our time and give birth to a new era of human flourishing.

David Tacey’s Selected Bibliography:

The Darkening Spirit: Jung, Spirituality, Religion (2013):

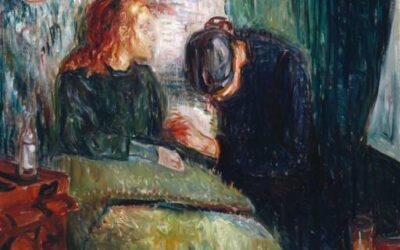

In this book, Tacey offers a Jungian perspective on the spiritual crisis of modernity. He argues that the rise of secular materialism has repressed the archetypal and numinous dimensions of human experience, leading to a “darkening of the spirit.” Tacey suggests that the rediscovery of these dimensions through a renewed engagement with mythology, ritual, and depth psychology is essential for personal and collective healing.

Edge of the Sacred: Jung, Psyche, Earth (2009):

Here, Tacey explores the ecological implications of Jung’s thought and argues for a new “eco-spirituality” that recognizes the sacredness of the natural world. He suggests that the modern dissociation from nature is a reflection of a deeper split within the human psyche, and that healing this split requires a re-enchantment of our relationship with the Earth. Tacey draws on indigenous wisdom traditions and the concept of the “anima mundi” to articulate a vision of psychic and ecological wholeness.

Gods and Diseases: Making Sense of Our Physical and Mental Wellbeing (2011):

In this book, Tacey examines the spiritual dimensions of health and illness, arguing that many physical and mental disorders have their roots in a neglect of the sacred. He suggests that the modern medical model, with its focus on biological reductionism, often fails to address the deeper existential and spiritual needs of patients. Tacey advocates for a more holistic approach to healing that recognizes the importance of meaning, purpose, and connection to something greater than oneself.

ReEnchantment: The New Australian Spirituality (2000):

In this early work, Tacey explores the emergence of a distinctly Australian spirituality that blends indigenous, Asian, and Western influences. He argues that this spirituality is characterized by a sense of connection to the land, a respect for Aboriginal wisdom, and an emphasis on direct experience of the sacred. Tacey suggests that this “new Australian spirituality” has the potential to offer a model for a more grounded, embodied, and ecologically-aware approach to religion.

The Jung Reader (2012):

In this edited collection, Tacey brings together a selection of Jung’s most important writings on spirituality, religion, and the modern world. He provides commentary and context for each piece, highlighting Jung’s prophetic insights into the spiritual crisis of modernity and his vision for a renewed relationship between psyche and cosmos. Tacey argues that Jung’s thought offers a vital resource for navigating the challenges of our time and imagining a more enchanted and soulful future.

How to Read Jung (2006):

In this accessible introduction to Jung’s thought, Tacey provides an overview of key Jungian concepts such as the collective unconscious, archetypes, individuation, and synchronicity. He argues that Jung’s ideas are essential for understanding the spiritual dimensions of human experience and the quest for meaning in a secular age. Tacey also explores Jung’s relevance for contemporary debates around ecology, politics, and social justice.

The Idea of the Numinous: Contemporary Jungian and Psychoanalytic Perspectives (2006):

In this edited collection, Tacey brings together a range of contemporary Jungian and psychoanalytic thinkers to explore the concept of the numinous. He argues that experiences of awe, wonder, and transcendence are essential for human flourishing, and that modern society neglects these experiences at its peril. Tacey suggests that a renewed appreciation for the numinous can help to heal the psychic and spiritual wounds of modernity and inspire a more reverent and responsible approach to life.

Post-Jungian Innovations:

While deeply rooted in the depth psychological tradition, Tacey’s work also extends and innovates upon classical Jungian theory in significant ways. He draws upon the insights of Jung and Neumann while creatively adapting them to shed light on the unique spiritual challenges and opportunities of the postmodern era.

One of Tacey’s key contributions is to expand the scope of Jungian analysis beyond the individual psyche to encompass the collective dynamics of culture and society. Whereas Jung focused primarily on the process of individual individuation, Tacey is concerned with the individuation of whole societies and the evolution of human consciousness on a global scale.

In books like The Darkening Spirit and Edge of the Sacred, Tacey applies Jungian concepts to diagnose the spiritual malaise of late modernity and to articulate the emergence of a “new spirituality” in the collective psyche. He suggests that just as individuals must integrate the contents of the personal unconscious to achieve wholeness, so too must cultures come to terms with the archetypal forces erupting from the collective unconscious in order to navigate times of crisis and transition.

Tacey also extends Jungian theory by emphasizing the importance of the “reality dimension” of archetypes in addition to their symbolic and psychological significance. For Jung, archetypes were primarily psychological factors, autonomous patterns of meaning that structure the psyche. While not denying this, Tacey argues that archetypes also have an ontological dimension, pointing to the objective reality of a sacred cosmos.

In this view, archetypes are not just subjective projections but “cosmic ordering principles” that permeate both psyche and world. They are the primal patterns through which the sacred discloses itself in human experience, the “footprints of the gods” that reveal a meaningful universe. By engaging with archetypes, we do not just access the depths of the unconscious; we come into alignment with the sacred architecture of the cosmos itself.

This ontological perspective informs Tacey’s approach to spirituality and his vision of a “re-enchanted” world. He suggests that the sacred is not just a human creation but an objective reality that breaks into time, an eruption of eternity into history. The task of spirituality is thus not just self-realization but attunement to a transcendent mystery, a surrender to the call of Being.

Tacey also builds upon Jungian theory by expanding the notion of the “religious function of the psyche.” For Jung, the psyche possessed a natural religious instinct, an innate drive towards meaning, wholeness, and transcendence. While affirming this, Tacey suggests that the religious function is not just an individual matter but a collective one, serving to bind societies together and align them with sacred purpose.

In books like Gods and Diseases and The Jung Reader, Tacey explores how the religious function expresses itself through the myths, symbols, and rituals of a culture. He argues that when this function is repressed or neglected, it leads to a sense of meaninglessness, alienation, and spiritual hunger. Conversely, when it is consciously engaged and integrated, it can serve as a powerful source of healing, creativity, and transformation.

Tacey sees this dynamic at work in the contemporary resurgence of interest in spirituality, which he interprets as a reactivation of the religious function in secular societies. As traditional religious frameworks have declined, the psyche has sought new channels for its spiritual impulses, giving rise to a proliferation of “spiritualities of life.” By attending to these emergent expressions of the sacred, we can help to midwife a new cultural mythology and a revitalized sense of existential meaning.

Another area where Tacey innovates upon Jungian theory is in his engagement with postcolonial and indigenous perspectives. He suggests that the depth psychological tradition has often been overly Eurocentric and dismissive of non-Western ways of knowing. In response, he calls for a “decolonization” of Jungian thought that takes seriously the insights of indigenous cultures and incorporates them into a more globally inclusive framework.

In Edge of the Sacred and ReEnchantment, Tacey explores how indigenous worldviews challenge Western assumptions about the nature of the sacred and the relationship between humans and the Earth. He suggests that by listening to the wisdom of traditional cultures, we can recover a sense of the sacredness of nature, the interconnectedness of all beings, and the importance of ritual and initiation. At the same time, he cautions against a romanticization of indigenous spirituality, emphasizing the need for critical discernment and intercultural dialogue.

Finally, Tacey extends Jungian theory by foregrounding the ecological dimensions of the individuation process. He argues that in an era of planetary crisis, the task of personal wholeness cannot be separated from the challenges of sustainability, social justice, and environmental healing. As such, he calls for an “ecospiritual” approach that recognizes the interdependence of psyche and cosmos, self and world.

In The Darkening Spirit and other works, Tacey suggests that the ecological crisis is ultimately a spiritual crisis, rooted in a collective psychic dissociation from the living Earth. By reconnecting with the anima mundi, the soul of the world, we can begin to heal this rift and rediscover our profound embededdness in the web of life. This requires not just a transformation of consciousness but a fundamental reorientation of our values, lifestyles, and systems to align with the needs of the planet.

For Tacey, this ecospiritual imperative is not separate from the individuation process but integral to it. In a time of global emergency, the call to wholeness is inextricable from the Great Work of cultural regeneration and Earth healing. As such, the depth psychological task becomes one of co-creating new myths, practices, and communities that can support the transition to a life-sustaining civilization.

Critiques and Retrospective:

While Tacey’s work has been widely influential in the fields of spirituality and psychology, it has also drawn critical responses from various quarters. Some scholars have questioned his interpretations of Jungian theory, suggesting that he departs too far from Jung’s original ideas or reads them through an overly ideological lens. Others have challenged his sweeping claims about the nature of contemporary spirituality, arguing that he overgeneralizes from limited data or ignores countervailing trends.

One common critique is that Tacey’s writing sometimes lapses into a romantic or uncritical embrace of alternative spiritualities. Critics suggest that he is too quick to celebrate the “rising sacred” in popular culture without sufficiently interrogating its shadow sides or potential pitfalls. They argue that his enthusiasm for the “new spirituality” can lead him to overlook its more narcissistic or regressive manifestations, as well as its complicity with consumerism and individualism.

Related to this, some commentators have accused Tacey of a certain “spiritual imperialism” in his approach to indigenous cultures. While he seeks to honor the wisdom of traditional societies, critics argue that he sometimes appropriates indigenous ideas in a superficial or decontextualized way, subsuming them into a universalizing spiritual framework. They suggest that a more nuanced and historically grounded engagement with indigenous realities is needed to avoid perpetuating colonial dynamics.

Other scholars have questioned the empirical basis of Tacey’s claims about the “spirituality revolution” and the emergence of a “new consciousness.” They argue that while there is indeed a significant spiritual seeking trend in Western societies, it is more ambiguous and multivalent than Tacey suggests. Critics point to the persistence of traditional religions, the rise of fundamentalisms, and the continued dominance of secular worldviews as complicating factors that Tacey tends to downplay in his account.

Finally, some commentators have challenged the political implications of Tacey’s spiritual vision. They suggest that his emphasis on individual transformation and archetypal forces can obscure the importance of systemic analysis and collective action. Critics argue that a focus on “changing consciousness” is insufficient without a concomitant commitment to dismantling oppressive structures and building alternative institutions. They call for a more politically engaged spirituality that links personal growth to social justice and ecological activism.

Notwithstanding these critiques, Tacey’s work remains a generative and provocative resource for scholars and seekers alike. His insistence on the centrality of the sacred in human life, his creative bridging of depth psychology and spirituality, and his call for a re-enchantment of the world continue to inspire new lines of inquiry and exploration.

In particular, Tacey’s diagnosis of the spiritual malaise of late modernity and his articulation of an emerging “new consciousness” have proved prescient and compelling. While the details of his analysis may be debated, his overall vision of a global spiritual awakening has been borne out by subsequent developments in many fields. The rise of the “spiritual but not religious” demographic, the mainstreaming of contemplative practices, and the growing interest in shamanism, psychedelics, and eco-spirituality all attest to the kind of shift that Tacey intuited.

Moreover, Tacey’s efforts to expand the scope of Jungian thought and to apply it to the challenges of a planetary era have helped to revitalize depth psychology for a new generation. By linking the individuation process to the larger arc of cultural evolution and the quest for sustainability, he has opened up new avenues for theory and practice. His call for a “decolonization” of Jungian ideas and a deeper engagement with indigenous wisdom has also sparked important conversations and self-reflection within the depth psychological community.

At the same time, the limitations and blind spots of Tacey’s approach must also be acknowledged and addressed. His work would benefit from a more systematic engagement with the diversity of spiritual expressions in the contemporary world, as well as a more critical examination of the power dynamics and historical contexts that shape them. A deeper dialogue with political economy, social ecology, and liberation theology could also help to ground his spiritual vision in the struggles for justice and sustainability.

As we grapple with the epochal challenges of our time, the work of David Tacey remains a vital resource and provocation. His unique synthesis of spirituality, psychology, and cultural studies offers a powerful lens for discerning the movements of soul in a time of crisis and transformation. While his ideas must be engaged critically and creatively, they provide an essential starting point for the task of rebuilding a world that honors the sacredness of life in all its forms. As we move into an uncertain future, may we be inspired by his vision of a re-enchanted Earth and a humanity awakened to its deepest potentials.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

0 Comments