Read the Dictionary of Early and Proto Mythology as a pdf

Read the Dictionary of Early and Proto Mythology as a pdf

The Dawn of Myth: Exploring the Origins of the Mythic Imagination

Dictionaries of Mythology's of Other Pantheons

The Dawn of Myth

Mythology, the collection of stories, symbols, and rituals that express a culture's understanding of the world, is a fundamental part of the human experience. From the epic tales of gods and heroes to the sacred rites of ancient religions, myth has shaped our perception of reality, given meaning to our lives, and connected us to something greater than ourselves.

But where do these myths come from? What are the origins of this uniquely human capacity for symbolic thought and storytelling? To answer these questions, we must journey back in time, to the very dawn of human culture.

In this exploration, we will trace the roots of mythic thought, drawing on insights from archaeology, anthropology, psychology, and comparative mythology. As Mircea Eliade suggests, these early symbolic expressions reflect humanity's fundamental relationship with the sacred, creating patterns that would resonate throughout history.

We will attempt to reconstruct the worldview of our distant ancestors and understand how they came to create the stories that would lay the foundation for all the mythologies to come.

The Birth of Symbol: The Emergence of Mythic Thought

Our story begins in the mists of prehistory, some 200,000 years ago, with the emergence of Homo sapiens. Physically, these early humans were not much different from us. But cognitively, they were on the cusp of a revolution.

This was the birth of what archaeologists call "behavioral modernity" - the emergence of abstract thought, symbolic language, and creative expression. It was a time when our ancestors first began to adorn themselves with beads and pendants, to create intricate tools and weapons, and to bury their dead with ritual and ceremony.

But perhaps the most significant innovation of this time was the creation of art. In cave paintings and carved figurines, we see the first glimmerings of the mythic imagination - the ability to represent the world not just as it is, but as it is perceived and understood through the lens of human consciousness.

According to Anthony Stevens, these symbolic expressions may be understood as manifestations of innate archetypal patterns, bridging our evolutionary past with our cultural present.

The Shamanic Vision: Paleolithic Cave Art

Some of the earliest and most spectacular examples of this new symbolic art are the cave paintings of the Upper Paleolithic period, such as those found at Lascaux and Chauvet in France, and Altamira in Spain. Dating back some 40,000 years, these paintings depict a rich array of animals - bison, horses, mammoths, lions - along with more enigmatic figures that seem to blend human and animal features.

For many researchers, these therianthropic (part-human, part-animal) figures are evidence of shamanic practices. Shamanism, which is still practiced by many indigenous peoples today, is a form of religious experience in which a specialist (the shaman) enters an altered state of consciousness in order to interact with the spirit world on behalf of their community.

In this view, the cave itself was seen as a portal to the spirit realm, and the paintings as a kind of map or guide for shamanic journeys. By depicting animals - which were often seen as spiritual beings or messengers - and hybrid shaman figures, these paintings may have served as a means of invoking or communicating with the powers that governed the hunt, the seasons, and the cycles of life and death.

The work of Victor Turner on ritual and liminality provides insight into how these cave spaces may have functioned as transitional zones where ordinary reality was suspended and transformation became possible.

The Great Mother: Paleolithic Venus Figurines

Alongside the cave paintings, another intriguing form of Paleolithic art are the so-called "Venus figurines". These are small statuettes of women, typically carved from soft stone, ivory, or bone, which emphasize certain bodily features - breasts, belly, buttocks - while minimizing or omitting others, like the face and feet.

The most famous example is the Venus of Willendorf, a 4.4-inch tall limestone figure from Austria, dated to around 25,000 BCE. With her ample curves and enigmatic lack of facial features, she has become an icon of prehistoric art.

But what do these figures represent? One theory is that they are early expressions of a Mother Goddess archetype - a divine feminine principle associated with fertility, nourishment, and the regenerative power of the earth. Just as the cave paintings may reflect a shamanic worldview centered on animal spirits, the Venus figurines may point to a parallel belief system focused on the mysteries of birth, death, and renewal.

The Eternal Return: The Bear Cult and the Cult of the Dead

This concern with the cycle of life and death is also evident in two other key aspects of Paleolithic culture - the bear cult and the cult of the dead.

The bear cult, which is attested in various forms across Eurasia, involved the ritual hunting, killing, and consumption of bears, followed by the ceremonial preservation of their bones. According to the mythologist Joseph Campbell, this practice reflects a belief in the bear as a sacred being who willingly sacrifices itself to sustain the human community, and who is then symbolically reborn through the proper treatment of its remains.

A similar logic may have informed the Paleolithic practice of burying the dead with grave goods and red ochre (a pigment that may have symbolized blood and life). Like the bear, the deceased were seen as embarking on a journey of transformation and renewal, one that required the support and participation of the living.

Arnold van Gennep's work on rites of passage illuminates how these burial practices structured the transition from life to death, providing a framework for understanding this profound transformation.

The Neolithic Revolution: The Rise of Agriculture and the Goddess

With the end of the last Ice Age around 12,000 years ago, human culture underwent a profound shift. In the Near East, the Fertile Crescent, and other parts of the world, people began to transition from a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one based on agriculture and settled village life. This was the Neolithic Revolution, and it would have far-reaching consequences for the development of mythic thought.

One of the most striking features of Neolithic culture is the proliferation of goddess figurines. From the "Seated Woman" of Çatalhöyük in Turkey to the "Snake Goddess" of Minoan Crete, these images suggest a continued preoccupation with feminine divinity, now associated more specifically with the fertility of crops and livestock.

This agricultural focus also manifested in a new form of sacred architecture - the stone circle. Sites like Göbekli Tepe in Turkey and Stonehenge in England were aligned with the movements of the sun and stars, suggesting a sophisticated understanding of the link between celestial cycles and the rhythms of planting and harvesting.

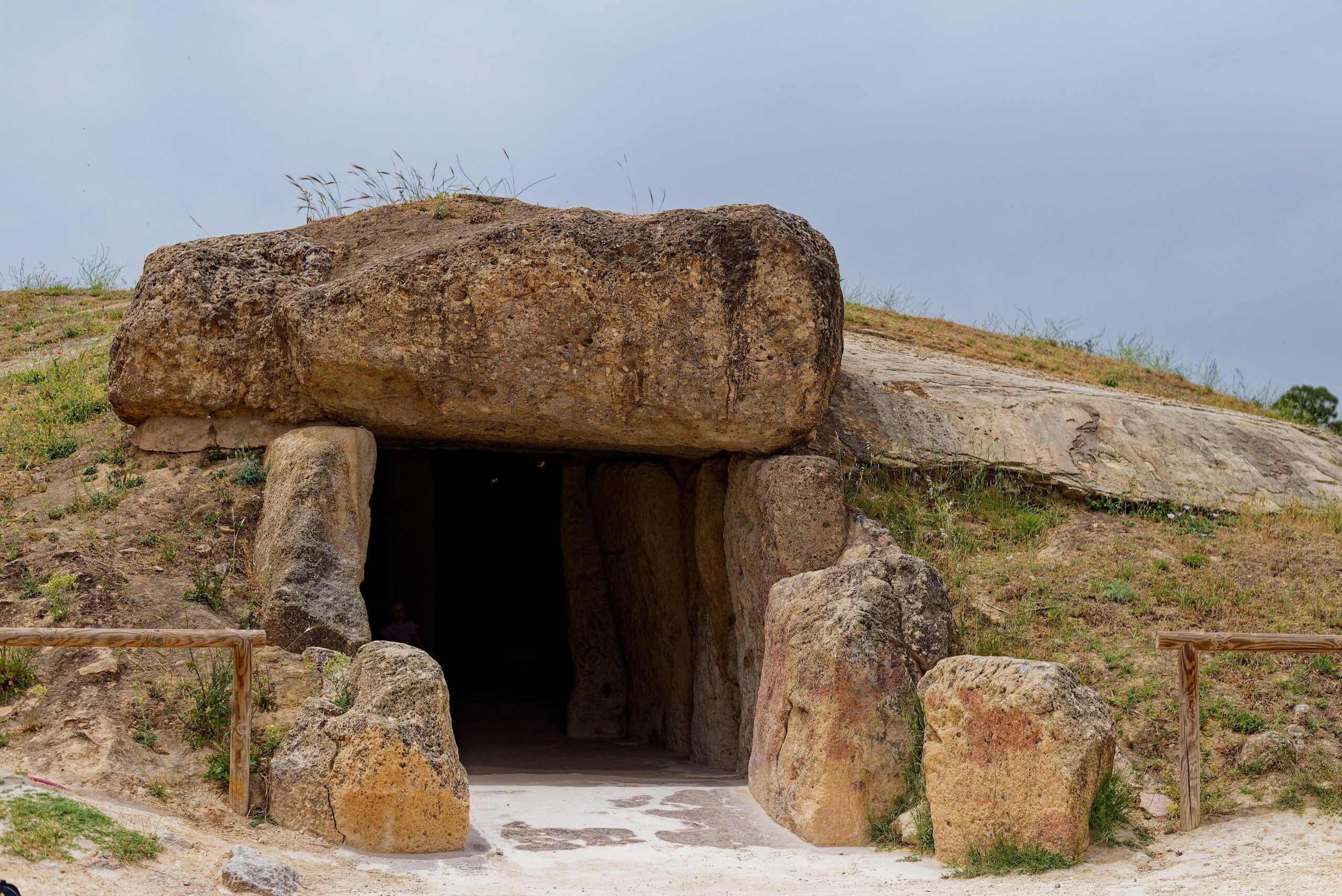

The emergence of Neolithic architecture, particularly in the form of dolmens and other megalithic structures, represents a significant development in humanity's expression of cosmic order through built environments.

At the same time, the practice of ancestor worship and the cult of the dead reached new heights in the Neolithic. Massive tomb structures like the megalithic dolmens and passage graves of Western Europe were designed to house the remains of the deceased, who were seen as powerful spirits capable of influencing the world of the living.

The Proto-Mythologies of the Ancient Near East

As the Neolithic gave way to the Bronze Age, and the first cities and states began to emerge in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley, the threads of mythic thought that had been developing since the Paleolithic began to weave together into more complex tapestries.

In the epic of Gilgamesh, the Babylonian Enuma Elish, and the Egyptian Pyramid Texts, we see the familiar themes of the sacred king, the dying and resurrecting god, and the cosmic battle between order and chaos - all motifs that can be traced back to earlier, prehistoric antecedents.

Yet these Bronze Age mythologies also introduced new elements that would prove influential for later traditions. The idea of a supreme creator god, the use of writing to codify and transmit sacred stories, and the development of more elaborate rituals and festival cycles - all these innovations laid the groundwork for the great religious systems of the ancient world.

Michael Meade's work on mythopoetic wisdom reminds us that these ancient stories continue to offer insights relevant to our modern psychological and social challenges.

The Mythic Imagination: Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

For the psychologist Carl Jung, the continuities between prehistoric and ancient mythologies were evidence of what he called the collective unconscious - a deep stratum of the psyche that transcends individual and cultural differences, and that is populated by universal symbols and archetypes.

Jung saw in the recurrent motifs of myth - the Great Mother, the Wise Old Man, the Hero, the Trickster - not just cultural constructs, but expressions of innate psychic structures that shape our perception and experience of the world. By studying these mythic patterns, he believed, we could gain insight into the workings of our own minds and the challenges of psychological growth and transformation.

Myth as a Mirror of the Human Journey

As we have seen, the origins of mythic thought are deeply rooted in the history of our species. From the shamanic visions of the Paleolithic to the goddess cults of the Neolithic to the epic narratives of the Bronze Age, myth has served as a means of making sense of the world, of connecting the human to the divine, and of charting the great cycles of birth, death, and renewal.

But myth is more than just a relic of our primitive past. As Jung recognized, the mythic imagination continues to shape our lives in profound and often unconscious ways. The stories we tell, the symbols we use, the very way we perceive reality - all bear the imprint of the archetypes and motifs that have echoed through human culture since time immemorial.

In this sense, the study of myth is not just an academic exercise, but a journey of self-discovery. By delving into the origins and evolution of mythic thought, we are also exploring the depths of our own psyche - the fears and desires, the dreams and visions that make us who we are.

So as we embark on this exploration of the proto-mythologies of the ancient world, let us keep in mind that we are not just looking at dusty artifacts or quaint superstitions. We are gazing into a mirror that reflects the human condition in all its mystery, terror, and wonder. And in the myths of our ancestors, we may just catch a glimpse of our own story, still unfolding, at the dawn of a new mythic age.

The ecological philosophy of David Abram reminds us that these mythic perceptions were grounded in a direct, sensuous engagement with the living world – an engagement that modern humans might benefit from rekindling.

Dictionary of Proto Mythology and Early Religion

The following sections provide a detailed look at key elements of proto-mythological thought and practice, drawing on archaeological evidence, psychological interpretation, and evolutionary connections to later mythological traditions.

Mal'ta-Buret' Culture: A Proto-Mythological Source?

The Mal'ta-Buret' culture, a Paleolithic society thriving in Siberia between 20,000 and 25,000 years ago, offers a remarkable window into the deep prehistory of human symbolic thought. The artifacts uncovered from this culture, including Venus figurines and bird-man statuettes, reveal early manifestations of archetypal themes that would later surface in mythologies across the world. The symbolic resonances between Mal'ta-Buret' and later traditions raise compelling questions about the origins of mythology and the potential universality of archetypal patterns in human cognition.

The Great Mother Archetype and Venus Figurines

The abundance of Venus figurines found at Mal'ta-Buret' strongly suggests an early conceptualization of the Great Mother archetype, a motif that recurs in goddess worship and sacred art from Mesopotamia to India. The exaggerated feminine features of these figures mirror those of the famous Venus of Willendorf and point to a deep-seated symbolic association between fertility, the feminine principle, and the cycles of nature.

Shamanic Symbolism and Animal-Human Hybrids

Among the most intriguing artifacts of Mal'ta-Buret' are the bird-man statuettes, which indicate early shamanic beliefs akin to those found in later Siberian and Native American traditions. This shamanic connection suggests that the culture possessed a proto-religious framework wherein humans mediated between natural and supernatural realms through symbolic transformation.

The Primordial Pair and Creation Myths

A notable artifact from Mal'ta-Buret' depicts a male and female standing back to back, a formation that hints at the foundational myth of a primordial pair, a concept that appears in global creation myths. Examples include Adam and Eve, the Norse Ask and Embla, and the Mayan Xmucane and Xpiacoc. While there is no direct evidence that Mal'ta-Buret' influenced these later narratives, the presence of dual-gendered figurines suggests an early recognition of the archetypal pair as a mythic foundation for human origins.

Celestial Alignments and Observatories

Archaeological Evidence: Throughout Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa, prehistoric peoples constructed structures with demonstrable astronomical alignments. Stonehenge (England, c. 3000-2000 BCE) features alignments with solstices and lunar cycles. Newgrange (Ireland, c. 3200 BCE) has a roof box that allows sunlight to penetrate its inner chamber only on the winter solstice. Nabta Playa (Egypt, c. 7000 BCE) contains stone circles and alignments marking stellar positions. Numerous other sites worldwide show similar attention to celestial phenomena, suggesting widespread astronomical observation among prehistoric peoples.

Mythological Significance: These alignments suggest that early humans developed sophisticated cosmologies connecting celestial movements with earthly cycles. Stone structures likely served both practical purposes (calendrical tracking) and ritual functions (marking sacred moments when cosmic forces manifested). The effort invested in these constructions indicates these were not merely observational tools but expressions of a worldview where celestial rhythms governed human activities.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, celestial alignments represent early human attempts to establish connection between conscious experience (earth-bound existence) and the greater cosmic patterns (collective unconscious). The regular movements of celestial bodies provided a visible manifestation of order amid the apparent chaos of existence.

The liminal qualities of these astronomical sites connect with Victor Turner's analysis of liminal spaces as transformative thresholds where ordinary reality is suspended and new possibilities emerge.

Venus Figurines

Archaeological Evidence: Over 200 small female figurines, collectively known as "Venus figurines," have been discovered across Europe and parts of Asia, dating from approximately 35,000 to 11,000 BCE (Upper Paleolithic period). Notable examples include the Venus of Willendorf (Austria, c. 25,000 BCE), the Venus of Lespugue (France, c. 25,000 BCE), and the Venus of Dolní Věstonice (Czech Republic, c. 29,000-25,000 BCE).

Mythological Significance: The widespread distribution and consistent stylistic elements of Venus figurines suggest they represented important mythological concepts across diverse Upper Paleolithic cultures. While traditional interpretations focused on fertility and "mother goddess" worship, contemporary archaeologists recognize multiple possible functions.

Psychological Interpretation: Venus figurines embody what Jung might call the archetypal feminine – representations of the anima mundi or world soul that precede personified goddess figures. Their exaggerated features suggest psychological emphasis on generative aspects of the feminine principle rather than its nurturing or relational qualities, which became more prominent in later goddess iconography.

This perspective aligns with the archetypal psychological approach developed by Anthony Stevens, who synthesizes evolutionary science with Jungian psychology to understand how archetypal patterns emerge from our biological heritage.

Cave Art and Animal Spirit Worship

Archaeological Evidence: Paleolithic cave paintings and engravings dating from approximately 40,000 to 12,000 BCE have been discovered throughout Europe, particularly in France (Lascaux, Chauvet) and Spain (Altamira). These artworks predominantly feature animals, including bison, horses, deer, mammoths, lions, and bears, often rendered with remarkable naturalistic detail.

Mythological Significance: The predominance and careful execution of animal imagery suggests these creatures held central importance in Paleolithic mythological thinking. Several interpretations have emerged: hunting magic, totemism, shamanic visions, and cosmological mapping.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, cave art represents early human encounter with what Jung would call the animal archetypes – powerful, autonomous psychic energies experienced as other-than-human yet intimately connected to human existence.

The ecological philosophy of David Abram offers insight into how these animal representations might reflect a perceptual reciprocity between humans and the more-than-human world, a participatory consciousness that modern humans have largely forgotten.

Solar Disk Worship

Archaeological Evidence: Circular gold disks, rock carvings of concentric circles, and sun-wheel designs appear across numerous prehistoric cultures from the Neolithic period onward. Notable examples include the Nebra Sky Disk (Germany, c. 1600 BCE), gold sun disks from Bronze Age Ireland and Scandinavia, circular petroglyphs throughout Europe and the Americas, and solar symbols on pottery and ritual objects worldwide. Many megalithic structures show solar alignments, particularly with solstices and equinoxes, indicating ritual significance of solar cycles.

Mythological Significance: The prevalence of solar symbolism suggests early humans developed proto-mythic narratives around the sun's journey, powers, and relationship to human existence. The circular form likely represented completeness and cyclical renewal, while the sun itself embodied life-giving warmth, illumination, and timekeeping. The careful tracking of solar movements through megalithic alignments suggests mythological frameworks connecting solar cycles to human activities and cosmic order.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, the solar disk represents what Jung identified as the most universal symbol of consciousness itself – illuminating, differentiating, and life-sustaining. The prehistoric focus on solar symbolism suggests early recognition of consciousness as a central psychological principle, externalized and projected onto the most powerful visible celestial entity.

Bull and Cattle Symbolism

Archaeological Evidence: Bull imagery appears prominently across prehistoric cultures from at least 15,000 BCE onward. Cave paintings at Lascaux (France) and Altamira (Spain) feature detailed aurochs (wild cattle) imagery. The Neolithic settlement Çatalhöyük (Turkey, 7500-5700 BCE) contains numerous bull horn installations and bull-themed reliefs in domestic spaces. Bull figurines and bull-headed artifacts appear in Neolithic and Bronze Age contexts throughout Europe, the Near East, and India.

Mythological Significance: The widespread prominence of bull imagery suggests this animal held central mythological significance across diverse prehistoric cultures. Bulls likely symbolized virility, strength, and generative power. Their incorporation into domestic spaces at sites like Çatalhöyük suggests they represented protective forces and household prosperity. The careful burial of bull horns and skulls indicates these animals were not merely economic resources but carried significant ritual importance, possibly as intermediaries between human and divine realms.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, bull symbolism represents early human encounter with and attempt to integrate powerful instinctual energies. The bull embodies what Jung might call the untamed masculine archetype – generative, powerful, and potentially destructive when not properly related to. Unlike predatory animals that represented external threats, the bull's domestication made it an ideal symbol for the partially-tamed but still dangerous aspects of human nature itself.

Great Mother and Earth Goddess

Archaeological Evidence: Female figurines with emphasized reproductive attributes appear across Upper Paleolithic through Neolithic contexts (c. 40,000-4,000 BCE) worldwide. Beyond the Venus figurines already discussed, later examples include seated female figures from Çatalhöyük (Turkey) and the "Mother Goddess" figures from Neolithic Old Europe (particularly in modern Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece). Archaeological evidence suggests special treatment of clay (earth material) in ritual contexts, including figurines deliberately broken and buried in agricultural fields.

Mythological Significance: The widespread presence of female imagery suggests prehistoric development of mythological frameworks centered on feminine generative power. As humans transitioned from hunting and gathering to agriculture, the earth's fertility likely became associated with female reproductive capacity, generating proto-mythic narratives connecting women, earth, and agricultural abundance.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, the Great Mother imagery represents early human encounter with what Jung called the archetypal feminine – the psychological pattern of generative containment that both produces and nurtures life. The prevalence of these images suggests psychological recognition of the feminine principle as foundational to existence, predating and underlying more differentiated cosmic patterns.

Birth, Death and Rebirth Symbolism

Archaeological Evidence: Prehistoric burial practices worldwide show evidence of ritual treatment suggesting beliefs about continued existence or transformation after death. Red ochre (resembling blood) frequently appears in Paleolithic burials (from c. 100,000 BCE). Grave goods including tools, ornaments, and food suggest belief in needs beyond physical death. Burial positions often resemble the fetal position, suggesting connections between death and birth.

Mythological Significance: The consistent ritual treatment of the dead suggests prehistoric peoples developed proto-mythic frameworks understanding death as transformation rather than ending. The use of red ochre may represent symbolic "re-blooding" of the dead, preparing them for renewed life. The fetal positioning of bodies suggests intuitive recognition of death as preparation for rebirth, with the grave as symbolic womb.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, prehistoric death-rebirth symbolism represents early human encounter with what Jung identified as the central transformative pattern of the psyche. The consistent evidence for rebirth beliefs suggests intuitive recognition of psychological renewal through symbolic death—the universal pattern where ego dissolution precedes psychic reorganization at higher levels of integration.

These ancient ritual practices connect with van Gennep's understanding of death rites as transformative passages rather than merely terminal events.

Animal Shamanism and Therianthropic Beings

Archaeological Evidence: Cave paintings and artifacts from the Upper Paleolithic period (c. 40,000-10,000 BCE) feature what appear to be composite human-animal figures, including the "Sorcerer" of Trois-Frères cave (France) with deer antlers and tail, the "Lion-Man" statuette from Hohlenstein-Stadel (Germany, c. 35,000-40,000 BCE) showing a human body with lion head, and numerous other therianthropic (part-human, part-animal) representations.

Mythological Significance: These therianthropic representations suggest prehistoric development of proto-mythic frameworks centered on transformation between human and animal states. Rather than fixed categories, humans and animals appear to have been understood as different manifestations of shared spiritual essence. These images likely represent shamanic practitioners who, through altered consciousness states, experienced transformation into animal form to access special powers or knowledge.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, therianthropic imagery represents early human recognition of what Jung called the animal archetypes – autonomous psychological energies experienced as having specific animal qualities while remaining intimately connected to human consciousness. The shamanic transformation into animal form symbolizes psychological capacity to access different modes of perception and cognition beyond ordinary human awareness.

The work of Michael Meade illuminates how these ancient shamanic practices continue to inform contemporary understanding of psychological transformation through mythic engagement.

Cosmic Tree and World Axis

Archaeological Evidence: Tree imagery appears prominently in prehistoric art worldwide, often in contexts suggesting more than decorative purpose. Wooden posts at Neolithic sites, including Göbekli Tepe (Turkey, c. 10,000 BCE), appear in central positions suggesting ritual significance. Archaeological evidence indicates special treatment of certain trees, with offerings placed around their bases or in hollow trunks.

Mythological Significance: The prominence of tree imagery suggests prehistoric development of proto-mythic frameworks centering on trees as connectors between cosmic realms. Trees, with roots below ground, trunks at human level, and branches reaching skyward, provide natural symbols for connections between underworld, middle world, and upper world. Their annual cycle of apparent death and rebirth would have provided visible manifestation of transformation principles.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, the cosmic tree represents what Jung identified as the central symbol of psychic integration – the axis connecting different levels of consciousness. The tree embodies psychological understanding of the self as extending both below (into personal and collective unconscious) and above (into transpersonal awareness) ordinary consciousness.

This vertical axis symbolism relates to Mircea Eliade's concept of the axis mundi as a point where different planes of existence intersect, allowing communication between cosmic realms.

Twin and Dual Divinities

Archaeological Evidence: Paired figures appear in prehistoric art from the Upper Paleolithic through Neolithic periods. Notable examples include double "Venus" figurines from Neolithic Europe, paired anthropomorphic pillars at Göbekli Tepe (Turkey, c. 10,000 BCE), and dual burial arrangements where bodies are positioned symmetrically or in mirror-image poses.

Mythological Significance: The prevalence of paired imagery suggests prehistoric development of proto-mythic frameworks organizing cosmic forces into complementary dualities. Rather than representing absolute opposites, these pairings likely embodied complementary principles working in dynamic balance. The paired figures at sites like Göbekli Tepe suggest early conceptualization of cosmic forces as relational rather than singular.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, twin imagery represents early human recognition of what Jung called the principle of enantiodromia – the tendency of psychological energies to manifest in complementary pairs that both oppose and complete each other. The prevalence of dual imagery suggests intuitive psychological understanding that consciousness develops through relationship with "the other" rather than through isolation.

Labyrinths and Spiral Symbols

Archaeological Evidence: Spiral and labyrinthine patterns appear in prehistoric art worldwide from the Neolithic period onward, with some possible Paleolithic precursors. Notable examples include spiral petroglyphs at Newgrange passage tomb (Ireland, c. 3200 BCE), spiral decorations on Neolithic pottery throughout Europe, and labyrinthine stone arrangements in Northern Europe and the Mediterranean region.

Mythological Significance: The prevalence of spiral and labyrinth imagery suggests prehistoric development of proto-mythic frameworks centered on transformative journey patterns. Unlike linear paths, spirals and labyrinths represent journeys that repeatedly change direction while maintaining overall progress toward (or away from) a center. Their frequent association with tomb entrances suggests mythological understanding of death as complex transformative journey rather than simple transition.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, spiral and labyrinth imagery represents early human recognition of what Jung identified as the individuation pattern – psychological development occurring not through direct progression but through cyclical movements that repeatedly approach and retreat from central meaning. The prevalence of these symbols suggests intuitive psychological understanding that transformation requires disorientation and surrender of control.

The labyrinthine journey resonates with Victor Turner's understanding of liminality as a necessary phase of transformation, where conventional structures are dissolved before new integration can occur.

Water and Primordial Ocean Symbolism

Archaeological Evidence: Special treatment of water sources appears in prehistoric contexts worldwide. Springs, rivers, and lakes show evidence of ritual offerings from at least the Mesolithic period (c. 10,000-5,000 BCE), with artifacts deliberately placed in watery locations. Megalithic structures and settlements frequently incorporate alignment with water features or symbolic representation of water through undulating lines and patterns.

Mythological Significance: The consistent ritual focus on water suggests prehistoric development of proto-mythic frameworks centering on water as primordial substance and transformative medium. Water's fundamental role in sustaining life while also presenting danger would have established it as primary ambivalent force requiring mythological interpretation and ritual management.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, water symbolism represents early human recognition of what Jung identified as the primary symbol for the unconscious – the undifferentiated psychological state preceding the emergence of distinct consciousness and surrounding it throughout development. The ritual focus on water suggests intuitive psychological understanding of the unconscious as both source of life and potentially dangerous realm requiring careful negotiation.

Bird and Flight Symbolism

Archaeological Evidence: Bird imagery appears prominently in prehistoric art worldwide from Paleolithic through Neolithic periods. Cave paintings feature birds alongside mammals, sometimes in apparent shamanic or transformational contexts. Bird figurines, particularly of waterfowl, appear in Paleolithic through Bronze Age contexts. Archaeological evidence indicates special treatment of bird remains, including ceremonial burial of raptors and corvids.

Mythological Significance: The prominence of bird imagery suggests prehistoric development of proto-mythic frameworks associating birds with transcendent movement between realms. Unlike earth-bound mammals, birds visibly moved between ground level and sky, making them natural symbols for beings capable of traversing cosmic domains. Their migration patterns, appearing and disappearing seasonally, would have suggested knowledge of distant realms beyond human experience.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, bird symbolism represents early human recognition of what Jung called the transcendent function – the psychological capacity to rise above immediate circumstances and achieve broader perspective. The ritual focus on birds suggests intuitive psychological understanding that human consciousness, though typically "earthbound" in immediate concerns, contains potential for expansive awareness beyond personal limitations.

Ancestral Worship and Skull Cults

Archaeological Evidence: Special treatment of human skulls and other remains appears in prehistoric contexts worldwide from at least the Upper Paleolithic period (c. 40,000 BCE) onward. Notable examples include plastered and decorated skulls from Jericho (c. 7000 BCE) and other Neolithic Near Eastern sites, skull-cups and deliberately modified cranial remains from European Paleolithic and Mesolithic contexts, and special burial arrangements emphasizing skulls.

Mythological Significance: The consistent special treatment of human remains, particularly skulls, suggests prehistoric development of proto-mythic frameworks centered on continued presence and influence of the dead. Rather than representing complete separation, death appears to have been understood as transformation into different mode of existence where ancestors remained accessible through proper ritual engagement.

Psychological Interpretation: From a depth psychological perspective, ancestral worship represents early human recognition of what Jung called the parental complexes and collective unconscious – the psychological inheritance from previous generations that continues to shape conscious experience. The ritual focus on skulls suggests intuitive psychological understanding that the "minds" of the dead (their patterns of thinking, valuing, and perceiving) continue to influence the living through internalized patterns.

This ancestral connection connects with Lionel Corbett's exploration of how archetypal patterns manifest through personal and familial history, creating bridges between individual experience and collective inheritance.

Significant Cave Art and Artifacts

Altamira Cave Paintings

Location: Cantabria, Spain

Date: Upper Paleolithic, approximately 36,000 to 13,000 years ago

Deep in the caverns of Altamira, in present-day Spain, lies one of the most breathtaking examples of Paleolithic art ever discovered. Here, in the flickering light of ancient lamps, early humans created a masterpiece of proto-mythological expression.

The walls of the cave are adorned with over 900 paintings, predominantly featuring large mammals such as bison, horses, and deer. But it is the Great Hall of the Bulls that is most awe-inspiring - a 30-meter long chamber where herds of bison, some over two meters long, are depicted with an astonishing sense of naturalism and dynamism.

For early researchers, these paintings were seen as mere decorations or hunting magic. But more recent interpretations suggest a deeper symbolic and potentially mythic significance. The cave itself may have been seen as a sacred space, a "womb of the earth" where shamanic rituals were performed. The animals, painted with such vivid detail, may have been seen as spiritual beings or totemic ancestors, their lifelike representation a way of invoking their power.

This interpretation aligns with Mircea Eliade's analysis of sacred space as a point of connection between cosmic planes, where communication with otherworldly realms becomes possible.

Lascaux Cave Paintings

Location: Dordogne, France

Date: Upper Paleolithic, approximately 17,000 years ago

In 1940, four teenage boys stumbled upon a cave system in southwestern France that would come to be recognized as one of the crowning achievements of Paleolithic art. The Lascaux cave, with its spectacular paintings of bulls, horses, deer, and other animals, provides a mesmerizing glimpse into the mythic imagination of our early ancestors.

The Lascaux paintings are remarkable for their artistic sophistication and their sense of compositional unity. In the "Hall of the Bulls," for instance, we find a stunning array of animals arranged in a semi-circular composition, their dynamic poses suggesting a sense of movement and vitality. The largest of these, a bull measuring over 5 meters long, is a masterpiece of naturalistic representation.

One of the most enigmatic images in Lascaux is the so-called "Shaft Scene," located in a deep recess of the cave. Here we find a human figure with a bird's head, apparently falling or jumping in front of a disemboweled bison. Nearby is a bird on a stick and a rhinoceros seemingly charging off into the distance. This strange composition has been interpreted in various ways - as a shamanic trance scene, a mythic narrative, or an astronomical chart.

The transformative nature of these cave spaces resonates with Arnold van Gennep's analysis of ritual transitions, where traditional boundaries dissolve and new identities emerge.

Chauvet Cave Paintings

Location: Ardèche, France

Date: Upper Paleolithic, approximately 30,000 to 32,000 years ago

In 1994, a group of speleologists exploring a cave system in southern France made a discovery that would revolutionize our understanding of Paleolithic art. The Chauvet cave, named after one of its discoverers, contained some of the oldest and most spectacular cave paintings ever found, dating back some 30,000 to 32,000 years.

What makes the Chauvet paintings so remarkable is not just their age, but their artistic sophistication and emotional power. The walls of the cave are adorned with over 1,000 images, predominantly of animals such as horses, cattle, mammoths, lions, bears, and rhinoceroses. These animals are depicted with an astonishing sense of realism and dynamism, their forms conveyed through subtle shading and skillful use of the cave's natural contours.

But it is not just the technical skill of the Chauvet artists that astounds us. It is the sense of a deep spiritual and mythic connection between humans and animals. Many of the animals are depicted in pairs or groups, suggesting a sense of relationship and interaction. Some are shown with exaggerated features, such as enlarged eyes or muzzles, hinting at a kind of supernatural or totemic power.

Particularly striking are the depictions of dangerous predators such as lions, bears, and rhinoceroses. These animals are not shown as prey or adversaries, but as powerful spiritual beings, perhaps even as divine forces. The fact that they are depicted in the deepest, darkest recesses of the cave suggests a kind of initiatory encounter, a journey into the realm of primal forces.

The ecological perspective of David Abram helps us understand how these cave paintings might reflect a phenomenological engagement with the animal world that modern humans have largely lost.

Hohle Fels Venus

Location: Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Date: Upper Paleolithic, approximately 40,000 to 35,000 years ago

In 2008, archaeologists excavating the Hohle Fels cave in southwestern Germany unearthed a small figurine that would challenge our understanding of the origins of art and symbolic thought. The Hohle Fels Venus, carved from mammoth ivory and standing just over 6 centimeters tall, is the oldest known depiction of the human form, dating back some 40,000 years.

What makes the Hohle Fels Venus so remarkable is not just its age, but its explicit sexuality. The figurine depicts a woman with exaggerated breasts, belly, and vulva, her head and limbs reduced to abstract protrusions. This emphasis on female sexual characteristics has led many researchers to interpret the figurine as a fertility symbol or a representation of a mother goddess.

But the Hohle Fels Venus is not just a static icon. Closer examination reveals that the figurine was designed to be held or worn, with a small loop at the top suggesting that it may have been used as a pendant. This implies a kind of intimate, tactile relationship between the object and its owner, perhaps as a talisman or a sacred object used in ritual.

The discovery of the Hohle Fels Venus, along with other early "Venus figurines" from across Europe, suggests that the veneration of the female form and the feminine principle may have been one of the earliest manifestations of symbolic thought and religious belief.

The evolutionary perspective of Louise Barrett helps us understand how symbolic thinking like that represented by the Venus figurines evolved in relation to environmental and social pressures.

The Lion Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel

Location: Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Date: Upper Paleolithic, approximately 40,000 years ago

In 1939, archaeologists excavating the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in Germany uncovered a fragmented figurine that would come to be known as the Lion Man. Painstakingly reconstructed from over 200 ivory fragments, the Lion Man stands nearly 30 centimeters tall and depicts a being with a human body and a lion's head.

The Lion Man is a masterpiece of Paleolithic art, carved with remarkable skill and attention to detail. The figure stands upright, its feline head gazing forward with an expression of serene power. Its human body is lean and muscular, with clear indications of male genitalia. The overall impression is one of a hybrid being, a fusion of human and animal traits.

The significance of the Lion Man has been much debated by scholars. Some see it as a representation of a shamanic transformation, a depiction of a human taking on the power and attributes of the lion. Others interpret it as a therianthropic deity, a god who embodies both human and animal characteristics. Still others see it as a symbolic representation of the unity of nature and culture, a recognition of the interconnectedness of all living beings.

What is clear is that the Lion Man represents a significant development in the evolution of symbolic thought and mythic consciousness. The blending of human and animal traits suggests a worldview in which the boundaries between different orders of being were fluid and permeable.

This deep mythology of human-animal hybridity connects with Lionel Corbett's work on how archetypal images bridge the human and the sacred, creating pathways for psychological and spiritual transformation.

The Venus of Willendorf

Location: Willendorf, Austria

Date: Upper Paleolithic, approximately 25,000 years ago

Discovered in 1908 by a workman excavating a site in Austria, the Venus of Willendorf has become one of the most iconic and enigmatic images of Paleolithic art. Standing just over 11 centimeters tall, this limestone figurine depicts a woman with exaggerated breasts, belly, and buttocks, her head covered in what appear to be braided or coiled strands of hair.

The Venus of Willendorf is one of many so-called "Venus figurines" that have been found across Europe and Asia, dating from the Upper Paleolithic period. These figurines, which emphasize the female form and often feature pronounced sexual characteristics, have been interpreted in various ways by scholars.

One common interpretation is that they represent fertility goddesses or mother figures, symbolic embodiments of the generative power of nature. The exaggerated breasts and belly of the Venus of Willendorf, for example, may represent abundance and nourishment, while her ample buttocks and thighs may symbolize fertility and childbearing.

Another interpretation sees the Venus figurines as self-portraits or idealized representations of the female form. The fact that many of the figurines lack facial features or have their heads covered in elaborate hairstyles suggests that they may not have been intended as portraits of specific individuals, but rather as generic or archetypal images of womanhood.

From a Jungian perspective, the Venus figurines can be seen as expressions of the anima archetype, the feminine aspect of the collective unconscious. The emphasis on sexual characteristics and fertility may represent a projection of unconscious desires and fantasies, a way of giving form to the mysterious and alluring power of the feminine.

The archetypal analysis developed by Anthony Stevens helps us understand how these early symbolic representations might have emerged from the interplay of innate psychological patterns and environmental challenges.

Further Reading: Recommended Resources

The study of proto-mythology and early religious expression draws from multiple disciplines, including archaeology, anthropology, psychology, and comparative mythology. To deepen your understanding of these fascinating topics, we recommend the following resources:

Foundational Works on Comparative Mythology

- The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion by James George Frazer A seminal work in comparative religion and mythology, exploring parallels between the rites and beliefs of various cultures.

- The Masks of God series by Joseph Campbell A four-volume series examining the universal themes and variations in world mythologies, including Primitive Mythology, Oriental Mythology, Occidental Mythology, and Creative Mythology.

- The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell Campbell explores the monomyth or "hero's journey," a universal pattern in myths worldwide.

- The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History by Mircea Eliade Eliade examines the concept of cyclical time in mythological traditions, emphasizing the repetition of archetypal events.

- Myth and Meaning by Claude Lévi-Strauss A collection of essays discussing the role of myth in human society and its deeper structures.

Proto-Indo-European Studies

- In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth by J.P. Mallory Mallory investigates the origins and migrations of Indo-European peoples, shedding light on their cultural and mythological traditions.

- Deep Ancestors: Practicing the Religion of the Proto-Indo-Europeans by Ceisiwr Serith An exploration of reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religious practices and beliefs.

- Proto-Indo-European Mythology - Wikipedia An overview of the hypothesized myths and deities associated with the Proto-Indo-European language speakers.

- Proto-Indo-European Trees: The Arboreal System of a Prehistoric People by Paul Friedrich An exploration of the symbolic significance of trees in Proto-Indo-European culture.

- The New Comparative Mythology by C. Scott Littleton An assessment of Georges Dumézil's theories on Indo-European mythologies.

Depth Psychology and Myth

- The Archetypal Psychology of Anthony Stevens An exploration of Stevens' synthesis of evolutionary science and depth psychology in understanding archetypal patterns.

- Lionel Corbett: Exploring the Psyche, Spirituality, and the Sacred Corbett's work on how archetypal images bridge the human and the sacred, creating pathways for transformation.

- The Origins and History of Consciousness by Erich Neumann Neumann explores the development of human consciousness through mythological symbols.

- The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype by Erich Neumann An in-depth study of the mother archetype in various mythologies.

- What is the Golden Shadow in Jungian Psychology? An exploration of the positive aspects of the shadow archetype in Jungian psychology.

Anthropology and Ritual

- The Anthropology of Victor Turner An analysis of Turner's theories on ritual, liminality, and cultural performance.

- Arnold van Gennep and the Rites of Passage An exploration of van Gennep's framework for understanding transitional rituals across cultures.

- Mircea Eliade's Insights into the Sacred An examination of Eliade's theories on sacred space and time and their resonance with Jungian psychology.

- The Myth and Ritual School by Robert Ackerman A study of the scholars who emphasized the connection between myth and ritual, including J.G. Frazer and the Cambridge Ritualists.

- Michael Meade: Mythopoetic Wisdom for a Troubled World An exploration of Meade's contemporary applications of mythological wisdom.

Contemporary Perspectives

- The Origins of the World's Mythologies by E.J. Michael Witzel A comprehensive analysis tracing the origins and diffusion of mythological motifs across cultures.

- The Ecology of Enchantment: David Abram's Earth-Centered Philosophy An exploration of Abram's perspective on humans' relationship with the more-than-human world.

- The Birth of Architecture: Neolithic Dolmen An examination of early monumental architecture and its symbolic significance.

- Gods of the Ancient World: Literal Beings, Metaphorical Constructs, or Something In Between? An exploration of how ancient people understood their religious beliefs and deities.

- The Evolutionary Psychology of Louise Barrett Barrett's approach to situating cognition and symbolic thinking within the dynamics of life.

Key Archaeological Sites & Museums (Offsite Links)

- Lascaux Cave - Official website for the Lascaux Cave complex.

- Chauvet-Pont d'Arc Cave - UNESCO World Heritage Centre page for the Chauvet Cave.

- National Museum and Research Center of Altamira - Official museum website.

- Stonehenge - Official visitor information from English Heritage.

- Göbekli Tepe - UNESCO World Heritage Centre page for this key Neolithic site.