What are Newer Brain-Based Therapies for Trauma?

In recent years, there has been a surge of interest and research into novel therapies that target the brain and nervous system to treat the effects of psychological trauma. These emerging approaches leverage new insights from neuroscience to heal trauma in ways that go beyond traditional talk therapy. By working with the brain and body, they aim to resolve trauma stored in the nervous system and transform painful memories. This article will explore several of the most promising brain-based therapies, examining the current research, clinical applications, patient experiences, and the neuroscience of how they facilitate recovery from trauma.

Brainspotting

Brainspotting is a relatively new therapy developed by Dr. David Grand that uses specific eye positions to access and release traumatic memories and experiences stored in the subcortical brain. In a Brainspotting session, the therapist guides the client to find an eye position that activates a traumatic memory or somatic reaction. The client focuses on the spot while attending to their internal experience, allowing the trauma to be processed and released.

Research has shown Brainspotting to be effective for treating PTSD. A 2018 study found that a single session significantly reduced symptoms in 78% of subjects.1 Clinicians report that Brainspotting can often help clients who have been unresponsive to other trauma therapies.2 Patients describe feeling a deep release and reprocessing of traumatic experiences.3

Neurologically, Brainspotting appears to work by utilizing the midbrain to access and integrate traumatic reactions and memories that are “stuck” in the brainstem and not fully processed.4 By bringing these unconscious somatic reactions into conscious awareness, the individual can release the trauma. Brainspotting may be especially useful for resolving:

- Somatic symptoms and chronic pain related to trauma

- Flashbacks and intrusive memories

- Preverbal or early childhood traumas

- Single-incident shock traumas like accidents, assaults, or natural disasters

However, some individuals find the process of Brainspotting too intense, as it can lead to a rapid release of traumatic material. It may be less effective for more complex developmental traumas or attachment wounds on its own. As with all therapies, individual responses vary.

Lifespan Integration

Lifespan Integration (LI) therapy, developed by Peggy Pace, uses active imagination and a timeline of memories to help the brain establish a coherent autobiographical narrative. In an LI session, the client imagines traveling through time to different points in their life while the therapist reads a script. This repeated “time travel” and narration helps the brain link up neural networks to form a more cohesive sense of self.5

Several case studies have found LI effective for resolving trauma-related issues like:6,7

- Attachment wounds and developmental trauma

- Dissociative disorders

- Complex PTSD

- Self-esteem and identity issues

Patients often report a newfound sense of empowerment and a feeling that the past no longer defines them.7 LI tends to work gradually and gently compared to some other modalities. Clients often feel lighter and freer without being overwhelmed by traumatic memories.

The neurobiology of how LI works is still speculative. Some theorize it may involve the precuneus area of the brain, which is involved in autobiographical memory and assigning emotional significance to memories.8 LI may help update the emotional “tags” on memories so the individual no longer feels defined by past traumas.

LI can be helpful for attachment and developmental trauma but is less studied for shock trauma and single-incident PTSD. It is contraindicated for those with active psychosis or certain dissociative disorders. LI works best for those who are stable enough to tolerate imaginal exposure to past memories.

Parts-Based Therapies

Parts-based therapies are a family of approaches that view the psyche as composed of different parts, modes, or voices, each with its own perspective, needs, and roles. These parts often hold different experiences and memories, and trauma can cause them to become fragmented or polarized. Parts work aims to restore communication and harmony between parts. The goal is not to eliminate parts but to unburden them from extreme roles and help them work together as a team.

Internal Family Systems (IFS), developed by Richard Schwartz, is the most well-known parts-based approach. In IFS, parts are viewed as falling into three main categories:8

Exiles:

Parts that hold painful experiences and memories, often from childhood. Exiles are often frozen in the past and burdened by shame, fear, or anger.

Managers:

Parts that try to protect and control the system by keeping exiles exiled. Managers often hold rigid beliefs and use coping strategies like perfectionism, caretaking, or self-criticism to avoid vulnerability.

Firefighters:

Parts that emerge when exiles are activated and use extreme behaviors to combat emotional pain, such as addictions, violence, or self-harm.

In an IFS session, the client enters a meditative state to access their “Self,” the compassionate core beneath the parts. From this Self state, the client can dialogue with parts, witness their experiences, and unburden the pain they carry. The goal is not to eradicate parts but to appreciate their efforts to help and heal their pain. For example:

A client wants to work on her indecision about whether to return to school. As they focus inward, a procrastinating part emerges. Instead of judging it, the client thanks the part for sharing and asks why it procrastinates. The procrastinator reveals it is afraid of failing. It is carrying a memory of being humiliated by a teacher. Once witnessed with compassion, this painful memory can be released and the protector can let go of its fear, allowing the client to move forward more freely.

IFS is effective for a wide range of trauma-related issues, including PTSD, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and eating disorders.9,10,11 The deep, meditative states accessed in IFS likely engage similar brain networks as mindfulness meditation, which is known to strengthen emotional regulation, attention, and memory integration capacities in the prefrontal cortex.12 By compassionately witnessing traumatic memories held in various parts, the individual may be able to consolidate these fragments into a coherent whole.

IFS is a comprehensive approach that works well for complex cases where an individual has conflicting feelings and motivations. However, it requires the ability to differentiate parts and may not be indicated for those with fragile ego structures or difficulty with imaginal work. Some find the language of “parts” alienating or triggering.

Closely related to IFS, Process Therapy, also called Process-Oriented Psychology, is a parts-based approach developed by Arnold Mindell. It views parts as “processes” that are trying to help the individual and moves fluidly between inner work with parts and exploring outer real-world problems. Voice Dialogue, created by Hal and Sidra Stone, involves dialoguing between polarized parts or “selves” to create more balance and awareness. For example:

A man recovering from an abusive relationship notices his “Pleaser” part is activated around his partner. By dialoguing with this part, he discovers it emerged to appease his abusive father but is no longer serving him. He then dialogues with an opposite “Assertive” part to access its anger and boundaries. By consciously shifting between parts, he can respond more effectively.

Process Therapy and Voice Dialogue add valuable tools to help work with parts from different angles. They are particularly useful for interpersonal problems and inner conflicts. However, some individuals find it difficult to access distinct parts or voices.

Somatic Experiencing

Somatic Experiencing (SE) is a body-oriented therapy developed by Dr. Peter Levine based on his observations of how animals in the wild recover from trauma. SE focuses on gently releasing survival energies stuck in the body and nervous system after trauma. By attending to bodily sensations, impulses, and micro-movements in a safe, controlled way, the traumatic reaction can be gradually discharged.

Substantial research supports the efficacy of SE for treating trauma. Numerous studies have found SE effective for alleviating symptoms of PTSD, including:13,14,15

- Hyperarousal and hypervigilance

- Intrusive thoughts and flashbacks

- Avoidance and numbing

- Sleep disturbance

- Autonomic dysregulation

SE may work by engaging the parasympathetic nervous system to promote relaxation and the release of traumatic activation.16 Restoring fluidity and flow to the nervous system allows the body to return to equilibrium. SE can be helpful for shock trauma and single-incident PTSD, as well as complex trauma, developmental injury, and attachment wounds when combined with relational healing.

SE is a gradual, gentle approach that can feel less threatening for those who are dissociated or disconnected from their bodies. It relies less on verbal processing than some other therapies. SE may be especially beneficial for:

- Chronic syndromes like fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, headaches, or digestive issues that have been unresponsive to other treatments

- Trauma that is held somatically and is difficult to access through talk therapy

- Children and those with limited language or cognitive capacities

- Individuals who do not want to engage in lengthy trauma narratives

However, SE requires the ability to track sensations and may not be appropriate for those with poor interoceptive awareness or somatization under stress. Exclusive reliance on SE without cognitive processing may be insufficient for some individuals to create meaning from their trauma.

Neuromodulation Techniques

An exciting area of trauma treatment involves neuromodulation techniques that use technology to change brainwave patterns or stimulate specific areas of the brain. The most researched of these is neurofeedback, which teaches individuals to shift their own brainwave patterns through real-time feedback.

Numerous studies have found neurofeedback effective for PTSD.17,18,19 Neurofeedback may help with:

- Regulating autonomic arousal and reducing hypervigilance

- Improving attention and executive functioning

- Reducing dissociation and emotional numbing

- Decreasing nightmares and sleep disturbance

QEEG brain mapping is often used to guide neurofeedback protocols by identifying areas of dysregulation. Neurofeedback may help correct brainwave patterns that are too fast, too slow, or poorly integrated.

Other neuromodulation techniques are also being explored. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) uses magnetic fields to stimulate the brain, while transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) uses mild electrical currents. While more research is needed, preliminary studies suggest these techniques may help alleviate PTSD symptoms when combined with therapy, potentially by modulating neural networks involved in emotional reactivity and regulation.20,21

Neuromodulation likely works by helping to strengthen emotional regulation capacities mediated by the prefrontal cortex and recalibrating circuits involved in the stress response.22 These techniques can be powerful tools as part of a broader treatment plan but require specialized equipment and trained providers. Neurofeedback can be costly and may be inaccessible to some. Neuromodulation is promising but still an emerging field.

Ketamine-Assisted Psychotherapy

The use of ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic, in conjunction with psychotherapy is one of the most exciting developments in trauma treatment in recent years. Ketamine induces a temporary dreamlike state that can enable individuals to access and process traumatic memories from a place of safety and emotional distance.

Substantial research, including randomized controlled trials, has demonstrated the efficacy of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for treatment-resistant PTSD.23 Participants often report rapid and dramatic reductions in:

- Intrusive re-experiencing like flashbacks and nightmares

- Avoidance of trauma reminders

- Hyperarousal symptoms like hypervigilance and exaggerated startle response

- Negative mood and cognitions

Patients describe the ability to revisit traumatic memories without being retraumatized and to find new perspectives and insights.24 Ketamine’s dissociative effects may provide a “window of plasticity” in which traumatic memories can be updated and reconsolidated in a less emotionally charged way.25 Ketamine also stimulates neurogenesis and synaptogenesis, the growth of new neurons and neural connections.26 This may allow the brain to establish new pathways that bypass or override trauma-related patterns.

Ketamine-assisted psychotherapy can be particularly helpful for:

- Severe, chronic PTSD that has not responded to other treatments

- Individuals with a high degree of dissociation, depersonalization, or memory gaps

- Those who feel unable to verbally engage with traumatic memories due to intense emotional activation

- Complex cases with significant comorbidities like treatment-resistant depression, chronic pain, or substance abuse

However, ketamine is a powerful substance that can induce challenging altered states. It may not be appropriate for those with a history of psychosis, cardiovascular conditions, or active substance abuse. Preparation and integration sessions with a skilled therapist are essential to contain and ground the experience. More research is needed on the long-term efficacy and safety of this approach.

Myofascial and Movement Therapies

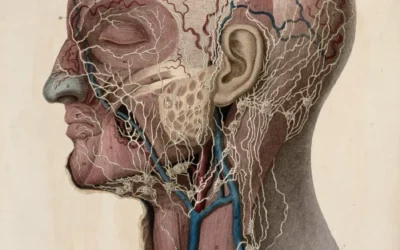

While psychotherapy and neuromodulation work from the top down, bodywork and somatic therapy can complement them by working from the bottom up. Trauma is not just stored in the brain but in the fascia, the connective tissue that surrounds every organ, muscle, and nerve. When we experience stress or trauma, the fascia tightens to protect us, but over time this chronic tension can lead to pain, restricted movement, and blocked emotions. Myofascial release and other forms of bodywork aim to gently release these chronically held tension patterns and restore alignment and ease in the body.

In particular, the work of Ida Rolf, known as Rolfing or Structural Integration, focuses on organizing the body in relation to gravity. Dr. Rolf found that physical and emotional traumas can disorient the body’s relationship to gravity, requiring extra effort and tension to stay upright. By systematically lengthening and repositioning the fascia, Rolfing aims to create a more balanced and efficient structure, with the head, shoulder, thorax, pelvis, and legs vertically aligned and horizontally oriented.27

Preliminary research suggests that Rolfing may help with a variety of conditions including:28,29

- Chronic pain and fibromyalgia

- Anxiety and depressive disorders

- Eating disorders and body image issues

- Insomnia and fatigue

- Autonomic dysregulation

While more research is needed specifically on trauma, many find Rolfing profoundly healing as a complement to psychological work. By releasing stuck patterns in the fascia and returning the body to its natural alignment, Rolfing may help increase interoception, build somatic resources, and process somatically-held emotions.30

As a slower, gentler alternative to Rolfing, myofascial release techniques popularized by John Barnes use sustained pressure to soften and lengthen fascia. Trauma-informed yoga and dance/movement therapies like the Trauma Center Trauma-Sensitive Yoga model31 developed by Bessel van der Kolk and David Emerson can help individuals safely re-inhabit their bodies and cultivate a felt sense of agency and empowerment.

While myofascial and movement therapies alone may not resolve trauma, they can play an important role as part of a holistic treatment plan. By bringing awareness to patterns of tension and holding in the body and providing corrective experiences, they can help individuals feel more regulated, embodied, and self-possessed. As trauma expert Peter Levine writes: “Trauma is a fact of life. It does not, however, have to be a life sentence. Not only can trauma be healed, but with appropriate guidance and support, it can be transformative.”32

Transforming trauma is a journey of many paths. The emerging frontier of brain-and-body-based therapies expands the map, offering new avenues to explore in the quest for healing. As we continue to study the impact of trauma on the nervous system and the processes that facilitate recovery, new possibilities are coming into view. It’s an exciting time as we forge a new paradigm that integrates the body, brain, and mind in the treatment of trauma. Harnessing the power of neuroplasticity, these approaches remind us that we are not prisoners of our past. With skilled support, safe embodiment, and compassionate self-awareness, it is possible to rewire the traumatized brain, befriend the wounded body, and reclaim the fullness of who we are. The path is not always easy, but it can lead us to places we never imagined possible.

References

- Hildebrand, A., Grand, D., & Stemmler, M. (2017). Brainspotting–the efficacy of a new therapy approach for the treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in comparison to Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 5(1).

- Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: The revolutionary new therapy for rapid and effective change. Sounds True.

- Corrigan, F. M., & Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: Recruiting the midbrain for accessing and healing sensorimotor memories of traumatic activation. Medical Hypotheses, 80(6), 759-766.

- Grand, D. (2021). Brainspotting: A New Brain-Based Psychotherapy Approach. The Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 31. 116-127.

- Pace, P. (2012). Lifespan integration: Connecting ego states through time. Lifespan Integration.

- Hu, X. S., & Bergström, H. (2019). Lifespan Integration Therapy for Complex Trauma and Dissociation (Case Series). Journal of Trauma & Treatment, 8, 438.

- Thorpe, K. (2016). Lifespan integration effectiveness in traumatized women. The Practicing Midwife, 19(1), 22-25.

- Schwartz, R. C. (2021). No bad parts: Healing trauma and restoring wholeness with the Internal Family Systems model. Sounds True.

- Schwartz, R. C., & Sweezy, M. (2020). Internal Family Systems Therapy (2nd Edition). Guilford Publications.

- Haddock, D. B., Weiler, L. M., Trump, L. J., & Henry, K. L. (2017). The efficacy of Internal Family Systems Therapy in the treatment of depression among female college students: A pilot study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(1), 131-144.

- Lucero, R., Jones, A. C., & Hunsaker, J. C. (2018). Using Internal Family Systems theory in the treatment of combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and their families. Contemporary Family Therapy, 40(4), 266-275.

- Prefrontal cortex in emotional regulation and integration: Implications for therapy of stress-related disorders. (2013) www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00074/full

- Brom, D., Stokar, Y., Lawi, C., Nuriel-Porat, V., Ziv, Y., Lerner, K., & Ross, G. (2017). Somatic Experiencing for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

: A Randomized Controlled Outcome Study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(3), 304-312. 14. Andersen, T. E., Lahav, Y., Ellegaard, H., & Manniche, C. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of brief somatic experiencing for chronic low back pain and comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1331108. 15. Briggs, J. P., Hayes, S. M., & Changaris, M. (2018). Somatic Experiencing Informed Therapeutic Group for the Care and Treatment of Biopsychosocial Effects upon a Gender Diverse Identity. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 53. 16. Payne, P., Levine, P. A., & Crane-Godreau, M. A. (2015). Somatic experiencing: Using interoception and proprioception as core elements of trauma therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 93. 17. Van der Kolk, B. A., Hodgdon, H., Gapen, M., Musicaro, R., Suvak, M. K., Hamlin, E., & Spinazzola, J. (2016). A randomized controlled study of neurofeedback for chronic PTSD. PLOS One, 11(12), e0166752. 18. Gapen, M. A., van der Kolk, B., Hamlin, E., Hirshberg, L., Suvak, M., & Spinazzola, J. (2016). A pilot study of neurofeedback for chronic PTSD. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 41(3), 251-261.

19. Reiter, K., Andersen, S. B., & Carlsson, J. (2016). Neurofeedback treatment and posttraumatic stress disorder: Effectiveness of neurofeedback on posttraumatic stress disorder and the optimal choice of protocol. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(2), 69-77. 20. Koek, R. J., Roach, J., Athanasiou, N., Korotinsky, A., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2020). Neuromodulation Treatments for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(10), 3170. 21. Clark, C. G., Bassi, C. J., Kim, I. A., et al. (2018). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation with resting-state network targeting for treatment-resistant depression in traumatic brain injury: A randomized, controlled, double-blinded pilot study. Journal of Neurotrauma, 35, 710-720. 22. Knox, M., Lentini, J., Cummings, T. S., McGrady, A., Whearty, K., & Sancrant, L. (2011). Game-based biofeedback for paediatric anxiety and depression. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 8(3), 195. 23. Feder, A., Costi, S., Rutter, S. B., Collins, A. B., Govindarajulu, U., Jha, M. K., … & Charney, D. S. (2021). A randomized controlled trial of repeated ketamine administration for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(2), 193-202. 24. Dore, J., Turnipseed, B., Dwyer, S., Turnipseed, A., Andries, J., Ascani, G., … & Wolfson, P. (2019). Ketamine assisted psychotherapy (KAP): Patient demographics, clinical data and outcomes in three large practices administering ketamine with psychotherapy. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 51(2), 189-198. 25. Krystal, J. H., Abdallah, C. G., Averill, L. A., Kelmendi, B., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Sanacora, G., … & Duman, R. S. (2017). Synaptic loss and the pathophysiology of PTSD: Implications for ketamine as a prototype novel therapeutic. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(10), 1-13. 26. Li, L., & Vlisides, P. E. (2016). Ketamine: 50 years of modulating the mind. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 612.

0 Comments