Who was Aristotle?

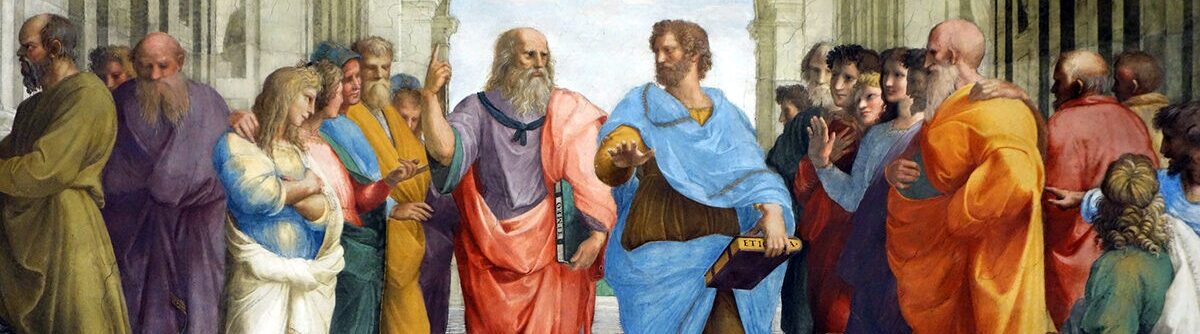

The ideas of Plato and Aristotle, two of the most influential philosophers in Western history, have had a profound impact on the development of depth psychology. From Carl Jung to James Hillman, many of the key figures in this field have grappled with the Platonic and Aristotelian legacies, seeking to integrate their insights into a deeper understanding of the human psyche. This essay will explore how the philosophical debates between Plato and Aristotle have shaped the theory and practice of depth psychology, and how various thinkers have aligned themselves with one tradition or the other.

Key Points:

- Plato and Aristotle, two of the most influential philosophers in Western history, have had a profound impact on the development of depth psychology.

- The philosophical lineage that led to Plato and Aristotle began with Socrates, whose ideas were preserved and elaborated by Plato in the Academy.

- Aristotle, who studied at Plato’s Academy, developed a philosophy that challenged and revised Platonic thought, emphasizing the importance of empirical observation and logical reasoning.

- The rivalry between Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum reflected the fundamental differences in their approaches to knowledge and reality.

- Plato’s theory of Forms and his emphasis on the transcendent realm of Ideas influenced the development of Jungian psychology and the concept of archetypes.

- Aristotle’s emphasis on empirical observation and the study of the natural world influenced the development of cognitive-behavioral psychology and other empirically-oriented approaches.

- The debate between Plato and Aristotle on the nature of knowledge and reality has implications for the way in which depth psychologists understand trauma, the therapeutic process, and the methods of inquiry.

- Contemporary depth psychologists continue to grapple with the philosophical questions and debates that have shaped the field from the beginning, seeking to integrate insights from both Platonic and Aristotelian thought.

- The influence of Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy extends beyond depth psychology to other disciplines, such as philosophy, religion, and the arts.

- The legacy of Plato and Aristotle in depth psychology is a testament to the enduring power of philosophical inquiry to illuminate the mysteries of the human soul.

The Lineage from Socrates to Aristotle

The philosophical lineage that led to Plato and Aristotle began with Socrates, the enigmatic Athenian thinker who sought to stimulate critical thinking through dialogue and questioning. Although Socrates left no written works of his own, his ideas were preserved and elaborated by his student Plato, who founded the Academy in Athens around 387 BCE. Plato’s philosophy was characterized by a belief in the existence of eternal, unchanging Forms or Ideas that exist beyond the realm of sensory experience. For Plato, the physical world was merely an imperfect reflection of these ideal Forms, and true knowledge could only be attained through rational contemplation and recollection of the soul’s prior existence.

Aristotle, who studied at Plato’s Academy for nearly 20 years, developed a philosophy that in many ways challenged and revised Platonic thought. While Plato emphasized the transcendent realm of Ideas, Aristotle focused on the concrete, sensory world of experience. He rejected Plato’s theory of Forms and instead sought to understand the universal principles and causes that underlie the particular phenomena of the world. Aristotle’s philosophy was characterized by a commitment to empirical observation, logical reasoning, and the systematic classification of knowledge.

The Rivalry between Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum

After Plato’s death in 347 BCE, Aristotle left the Academy and eventually founded his own school, the Lyceum, in 335 BCE. The Lyceum was characterized by a more empirical and scientific approach to knowledge than the Academy, reflecting Aristotle’s emphasis on observation and classification. The two schools developed rival approaches to philosophy, with the Academy emphasizing the contemplation of eternal truths and the Lyceum focusing on the investigation of the natural world.

This rivalry would have far-reaching consequences for the development of Western thought, as subsequent thinkers tended to align themselves with one tradition or the other. The Neoplatonists, such as Plotinus and Proclus, sought to elaborate and systematize Platonic philosophy, emphasizing the transcendent nature of the One and the soul’s ascent to the realm of Ideas. The medieval Scholastics, such as Thomas Aquinas, drew heavily on Aristotelian philosophy in their attempts to reconcile Christian theology with reason and natural science.

The Debate between Plato and Aristotle on Knowledge

At the heart of the disagreement between Plato and Aristotle was a fundamental difference in their theories of knowledge. For Plato, true knowledge was a matter of recollection, of remembering the eternal Forms that the soul had contemplated before its incarnation in the body. This theory implied a sharp distinction between the world of sensory appearances and the realm of true reality, accessible only through rational contemplation.

Aristotle, in contrast, rejected the theory of Forms and instead emphasized the importance of empirical observation and inductive reasoning in the acquisition of knowledge. For Aristotle, the universal principles or essences that underlie the particular phenomena of the world could be grasped through a careful study of those phenomena, rather than through a priori reasoning or mystical insight. This approach laid the foundations for the development of natural science and the scientific method.

The Influence of Platonic and Aristotelian

Thought on Depth Psychology The debate between Plato and Aristotle would have a profound influence on the development of depth psychology in the 20th century. Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, was deeply influenced by Platonic philosophy, particularly the idea of archetypes as universal patterns or forms that structure the collective unconscious. Jung’s concept of individuation, the process of psychological development and self-realization, also bears a resemblance to the Platonic idea of the soul’s ascent to the realm of Ideas.

Other depth psychologists, such as Erich Neumann and Marie-Louise von Franz, would develop Jung’s insights in a more explicitly Platonic direction. Neumann’s theory of the origins and development of consciousness, articulated in works such as The Origins and History of Consciousness and The Great Mother, drew heavily on Platonic and Neoplatonic ideas about the nature of the psyche and its relationship to the cosmos. Von Franz’s work on fairy tales and alchemy also emphasized the Platonic idea of universal archetypes and the symbolic or metaphorical nature of psychological truth.

At the same time, other depth psychologists would align themselves more closely with the Aristotelian tradition. Michael Fordham, a key figure in the development of analytical psychology in Britain, emphasized the importance of grounding Jungian concepts in empirical observation and scientific research. Fordham’s approach reflects an Aristotelian emphasis on the primacy of sensory experience and the need for theories to be based on empirical evidence.

Similarly, the school of ego psychology, developed by Freud’s daughter Anna Freud and others, tended to emphasize the importance of adaptation to external reality and the development of the ego’s capacities for reason and self-control. This emphasis on the rational, conscious mind reflects an Aristotelian perspective, in contrast to the more Platonic emphasis on the unconscious and the symbolic found in Jungian psychology.

The Metaphysics and Cosmology of Platonic and Aristotelian Philosophy

The differences between Plato and Aristotle extend beyond their theories of knowledge to their metaphysical and cosmological views. Plato’s philosophy is characterized by a dualistic ontology, which posits a sharp distinction between the eternal, unchanging realm of Ideas and the transient, mutable world of sensory appearances. This dualism is reflected in Plato’s theory of the soul, which holds that the soul is immortal and separable from the body, and that its ultimate destiny is to return to the realm of Ideas.

Aristotle, in contrast, rejected Platonic dualism in favor of a more naturalistic and immanent metaphysics. For Aristotle, form and matter are inseparable, and the sensible world is the primary reality. Aristotle’s cosmology posits a universe that is eternal and uncreated, with the Earth at the center and the heavenly bodies moving in perfect circular orbits. This cosmology reflects an Aristotelian emphasis on the order and regularity of the natural world, and the importance of empirical observation and rational analysis in understanding it.

These metaphysical and cosmological differences would have important implications for the development of depth psychology. Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, with its emphasis on universal archetypes and symbols, reflects a Platonic view of the psyche as a microcosm of the larger cosmos. The Jungian emphasis on the symbolic and the numinous also reflects a Platonic sensibility, as does the idea of the individuation process as a kind of spiritual or mystical quest.

In contrast, Freudian psychology, with its emphasis on the biological drives and the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping the psyche, reflects a more Aristotelian perspective. Freud’s theory of the mind as a complex mechanism, shaped by the interplay of conscious and unconscious forces, also reflects an Aristotelian emphasis on the natural world and the importance of causal explanation.

The Empirical and Epistemological Methods of Platonic and Aristotelian Psychology

The differences between Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy also have important implications for the empirical and epistemological methods of depth psychology. Platonic psychology, as exemplified by Jung and his followers, tends to emphasize the importance of intuition, imagination, and symbolic interpretation in understanding the psyche. Jungian psychology is often criticized for this lack of Cartesian empirical basis and its reliance on subjective or metaphorical modes of explanation.

Aristotelian psychology, in contrast, tends to emphasize the importance of empirical observation, experimental research, and causal explanation in understanding the mind. This approach is exemplified by the work of cognitive and behavioral psychologists, who seek to understand mental processes in terms of observable behavior and measurable physiological responses.

The tension between these two approaches has been a persistent theme in the history of depth psychology, with some thinkers seeking to integrate Platonic and Aristotelian perspectives, and others aligning themselves more closely with one tradition or the other. The school of archetypal psychology, founded by James Hillman, represents an attempt to revive and reinvent the Platonic tradition in a postmodern context, emphasizing the importance of imagination, myth, and metaphor in understanding the psyche.

Other depth psychologists, such as the existential analyst Rollo May and the humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers, have sought to integrate insights from both Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy. May’s emphasis on the importance of symbolic and mythical thinking reflects a Platonic sensibility, while his focus on the individual’s concrete lived experience reflects an Aristotelian perspective. Similarly, Rogers’ emphasis on the actualizing tendency and the importance of empathy and unconditional positive regard reflects an Aristotelian emphasis on the inherent potentialities of the individual, while his use of symbolic and metaphorical language reflects a Platonic sensibility.

Trauma and Knowledge in Platonic and Aristotelian Psychology

The differences between Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy also have important implications for the understanding of trauma and its impact on the psyche. Platonic psychology tends to emphasize the idea of trauma as a rupture or disruption in the soul’s connection to the realm of Ideas. Trauma, in this view, is a kind of forgetting or obscuration of the soul’s true nature, which can only be healed through a process of recollection and reintegration.

This Platonic understanding of trauma is reflected in Jung’s concept of the “shadow,” the repressed or denied aspects of the psyche that must be confronted and integrated in the process of individuation. It is also reflected in the work of depth psychologists such as Donald Kalsched, who has explored the ways in which trauma can create a split in the psyche between a vulnerable, wounded self and a protective, persecutory “self-care system.”

Aristotelian psychology, in contrast, tends to emphasize the idea of trauma as a disruption in the individual’s ability to function adaptively in the world. Trauma, in this view, is a kind of maladaptive learning or conditioning that can be overcome through a process of re-learning and behavioral change. This understanding of trauma is reflected in the work of cognitive-behavioral therapists, who seek to help individuals identify and change maladaptive patterns of thought and behavior.

Some depth psychologists, such as Peter Levine and Bessel van der Kolk, have sought to integrate Platonic and Aristotelian perspectives on trauma. Levine’s “somatic experiencing” approach emphasizes the importance of working with the body and the felt sense of trauma, reflecting an Aristotelian emphasis on the concrete and the embodied. At the same time, Levine’s use of symbolic and metaphorical language, such as his concept of the “felt sense,” reflects a Platonic sensibility.

Similarly, van der Kolk’s “body-oriented psychotherapy” approach emphasizes the importance of working with the physiological and neurological impacts of trauma, reflecting an Aristotelian perspective. However, his use of concepts such as “attunement” and “resonance” also reflects a Platonic emphasis on the importance of empathy and the intersubjective nature of healing.

The Legacy of Aristotelian and Platonic Thought in Depth Psychology

The influence of Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy on depth psychology continues to be felt to this day. Many contemporary thinkers in the field have sought to integrate insights from both traditions, while others have aligned themselves more closely with one or the other.

The school of archetypal psychology, founded by James Hillman, represents a contemporary revival of the Platonic tradition in depth psychology. Hillman’s emphasis on the importance of imagination, myth, and metaphor in understanding the psyche reflects a Platonic sensibility, as does his critique of the “literalizing” tendencies of modern psychology.

Other contemporary thinkers, such as the Jungian analyst and scholar Sonu Shamdasani, have sought to situate Jung’s work within the broader context of Western intellectual history, including the philosophical debates between Plato and Aristotle. Shamdasani’s scholarship has helped to illuminate the ways in which Jung’s thought was shaped by Platonic and Neoplatonic philosophy, as well as by the Aristotelian tradition of natural science.

In the field of psychoanalysis, thinkers such as Jacques Lacan and Julia Kristeva have drawn on Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy to develop new theories of the subject and the nature of language. Lacan’s concept of the “imaginary,” for example, bears a resemblance to Plato’s theory of Forms, while his emphasis on the importance of language and symbolic structures reflects an Aristotelian perspective.

Meanwhile, the influence of Aristotelian philosophy can be seen in the work of cognitive and behavioral psychologists, who seek to understand the mind in terms of observable behavior and measurable physiological responses. The emphasis on empirical research and scientific method in contemporary psychology also reflects an Aristotelian perspective, as does the focus on practical applications and evidence-based treatment approaches.

The Legacy and Influence of Aristotle

The influence of Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy on the development of depth psychology cannot be overstated. From Jung’s theory of archetypes to Hillman’s archetypal psychology, many of the key concepts and methods of this field have their roots in the philosophical debates of ancient Greece.

At the same time, the history of depth psychology also reflects the ongoing tension between Platonic and Aristotelian approaches to understanding the mind. While some thinkers have sought to integrate insights from both traditions, others have aligned themselves more closely with one or the other, emphasizing either the symbolic and imaginative dimensions of the psyche or the empirical and scientific study of behavior and cognition.

As depth psychology continues to evolve and develop in the 21st century, it will undoubtedly continue to grapple with the philosophical questions and debates that have shaped it from the beginning. By engaging with the rich intellectual heritage of Platonic and Aristotelian thought, contemporary thinkers can deepen their understanding of the psyche and develop new approaches to healing and transformation.

Ultimately, the legacy of Plato and Aristotle in depth psychology is a testament to the enduring power of philosophical inquiry to illuminate the mysteries of the mind and the human condition. As long as there are those who seek to understand the depths of the soul, the ideas of these two great thinkers will continue to inspire and guide us on our journey of self-discovery and understanding.

Implications for the Future of Depth Psychology

As we have seen, the influence of Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy on depth psychology has been profound and far-reaching. From the early days of psychoanalysis to the contemporary landscape of Jungian and post-Jungian thought, the ideas of Plato and Aristotle have served as a foundation for much of the theoretical and practical work in this field.

Going forward, it is clear that depth psychology will continue to grapple with the philosophical questions and debates that have shaped it from the beginning. As new theories and approaches emerge, they will inevitably be informed by the rich intellectual heritage of Platonic and Aristotelian thought, whether explicitly or implicitly.

One area where this influence is likely to be particularly strong is in the ongoing development of archetypal psychology. As a school of thought that explicitly aligns itself with the Platonic tradition, archetypal psychology is well-positioned to continue exploring the symbolic and imaginative dimensions of the psyche, and to develop new ways of working with myth, metaphor, and imagery in the therapeutic process.

At the same time, the influence of Aristotelian philosophy is likely to remain strong in the more empirically-oriented branches of depth psychology, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and neuroscience-informed approaches to treatment. As these fields continue to evolve and refine their methods, they will undoubtedly draw on the Aristotelian emphasis on observation, measurement, and practical application.

Another area where the influence of Platonic and Aristotelian thought may be felt is in the ongoing dialogue between depth psychology and other disciplines, such as philosophy, religion, and the arts. As depth psychologists seek to situate their work within a broader cultural and intellectual context, they will inevitably engage with the ideas of Plato and Aristotle, as well as other key figures in the history of Western thought.

Ultimately, the future of depth psychology will depend on its ability to integrate the insights of both Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy, while also remaining open to new ideas and approaches. By drawing on the rich intellectual heritage of the past, while also embracing the challenges and opportunities of the present, depth psychology can continue to evolve and grow in ways that are both theoretically rigorous and practically relevant.

Bibliography:

Aristotle. (1984). The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation. Edited by J. Barnes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Critchley, S., & Webster, J. (2013). Stay, Illusion!: The Hamlet Doctrine. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Freud, S. (1955). The Interpretation of Dreams. Edited by J. Strachey. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kalsched, D. (1996). The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. London: Routledge.

Lacan, J. (2006). Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English. Translated by B. Fink. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

May, R. (1969). Love and Will. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Moore, R., & Gillette, D. (1990). King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco.

Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Plato. (1997). Complete Works. Edited by J. M. Cooper. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company.

Plotinus. (1969). The Enneads. Translated by S. MacKenna. London: Faber and Faber.

Proclus. (1987). Proclus’ Commentary on Plato’s Parmenides. Translated by G. R. Morrow and J. M. Dillon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Shamdasani, S. (2003). Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York, NY: Viking.

Von Franz, M.-L. (1980). Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology. Toronto: Inner City Books.

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy.

Philosophy

0 Comments