Birth of Psyche Through the Invention of Architecture

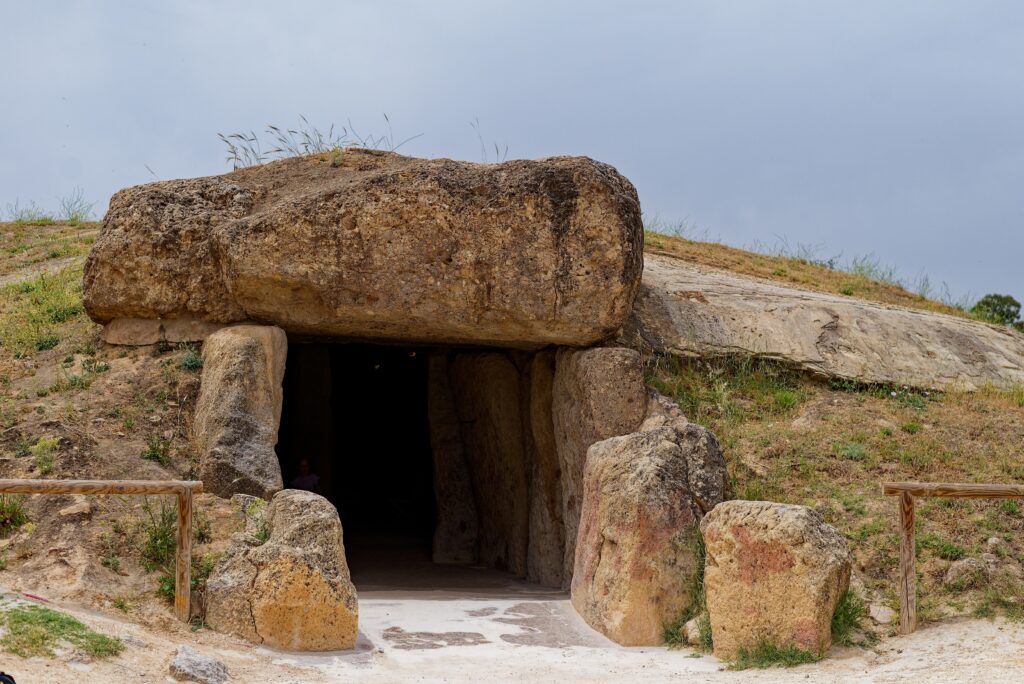

“Dolmen de Menga entrance: Massive stone portal of 6,000-year-old Neolithic tomb in Antequera, Spain.”

“La Peña de los Enamorados: Distinctive mountain face aligned with Dolmen de Menga, resembling human profile.”

Key Ideas:

- The invention of architecture during the Neolithic period marked a significant shift in human psychology and religion, creating a division between natural and man-made spaces and giving rise to new concepts of ownership, territoriality, and sacred spaces.

- The relationship between architecture and the awareness of death is explored, with the idea that built structures allowed humans to create a sense of permanence and continuity in the face of mortality.

- Neolithic dolmens and their alignment with the summer solstice may have played a crucial role in rituals related to death, the afterlife, and the cyclical nature of the cosmos.

- The astronomical alignment of the Dolmen de Menga is part of a larger pattern of archaeoastronomical significance in Neolithic monuments across Europe, suggesting a shared cosmological understanding among ancient societies.

- Neolithic art and architecture, including the use of red ochre and iron oxide paintings, may be linked to shamanic practices and altered states of consciousness.

- Peter Sloterdijk’s theory of spheres is applied to understand the evolution of human spatial awareness and the desire to recreate protected, womb-like spaces through architecture.

The fundamental nature of architecture and its role in human life is explored through various philosophical, psychological, and sociological perspectives.

Adventure Time with My Daughter

My daughter Violet likes the show Adventure Time. She loves mythology, creepy tombs, long dead civilizations and getting to be the first to explore and discover new things. I took my 6-year-old daughter to the Neolithic portal Tomb, or Dolmen, Dolmen de Menga in Antequera, while on a trip to Spain.

This ancient megalithic monument, believed to be one of the oldest and largest in Europe, dates back to the 3rd millennium BCE. It is made of 8 ton slabs of stone that archaeologists have a passing idea of how ancient people moved. It has a well drilled through 20 meters of bedrock at the back of it and it is oriented so that the entrance faces a mountain that looks like a sleeping giant the ancient builders might have worshiped. All of this delighted my daughter.

The dolmen’s impressive architecture features massive stone slabs, some weighing up to 180 tons, forming a 25-meter-long corridor and a spacious chamber. Inside, a well adds to the mystery, possibly used for rituals or as a symbol of the underworld.

What’s truly fascinating is the dolmen’s alignment with the nearby La Peña de los Enamorados mountain. During the summer solstice, the sun rises directly over the mountain, casting its first rays into the dolmen’s entrance, illuminating the depths of the chamber. This astronomical alignment suggests the ancient builders had a sophisticated understanding of the cosmos.

According to archaeoastronomical studies, the Dolmen de Menga might have served as a symbolic bridge between life and death, connecting the world of the living with the realm of the ancestors. The solstice alignment could have held great spiritual significance, marking a time of renewal, rebirth, and the eternal cycle of existence.

Sharing this incredible experience with my daughter and witnessing her awe and curiosity as she felt the weight of boulders that men had moved by hand, is a moment I’ll treasure forever. I reminded her that every time she has seen a building, be it a school or a sky-scraper, it all started here with the birth of architecture, and maybe the birth of something else too.

Thinking about prehistory is weird because thinking about the limits of our human understanding is trippy and prehistory is, by definition, before history and therefore written language, meaning we cant really know the subjective experience of anyone who was a part of it.

Talking to a child about the limits of what we as a species do or can know are some of my favorite moments as a parent because they are opportunities to teach children the importance of curiosity, intuition and intellectual humility than many adults never learn. Watching Violet contemplate a time when mankind didn’t have to tools or advanced scientific knowledge was a powerful moment when I saw her think so deeply about the humanity she was a part of.

What the Invention of Architecture did to Psychology

Anecdote of the Jar

by Wallace Stevens

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.It made the slovenly wildernessSurround that hill.The wilderness rose up to it,And sprawled around, no longer wild.The jar was round upon the groundAnd tall and of a port in air.It took dominion everywhere.The jar was gray and bare.It did not give of bird or bush,Like nothing else in Tennessee.

Prior to the advent of architecture, the world was an undivided, seamless entity, with no clear boundaries between human habitation and the natural environment. The construction of dolmens and other architectural structures shattered this unified perception, creating a new paradigm in which humans actively shaped and claimed portions of the earth for their own purposes. This act of claiming space and erecting structures upon it represented a profound psychological shift, as humans began to assert their agency and control over their surroundings.

The division of the world into natural and man-made spaces had far-reaching implications for human psychology. It fostered a sense of ownership and territoriality, as individuals and communities began to identify with and attach meaning to the spaces they created. This attachment to claimed spaces gave rise to new concepts of home, belonging, and identity, which were intimately tied to the built environment. Simultaneously, the unclaimed, natural world began to be perceived as a separate entity, one that existed beyond the boundaries of human control and understanding.

The impact of this division on religion was equally profound. The creation of man-made spaces, such as dolmens, provided a tangible manifestation of human agency and the ability to shape the world according to human beliefs and desires. These structures became sacred spaces, imbued with religious and spiritual significance, where rituals and ceremonies could be performed. The separation of natural and man-made spaces also gave rise to new religious concepts, such as the idea of sacred and profane spaces, and the belief in the ability of humans to create and manipulate the divine through architectural means.

The significance of this division between natural and man-made spaces is beautifully captured in Wallace Stevens’ anecdote of the jar. In this short poem, Stevens describes placing a jar in a wilderness, which “took dominion everywhere.” The jar, a man-made object, transforms the natural landscape around it, asserting human presence and control over the untamed wilderness. This simple act of placing a jar in the wild encapsulates the profound psychological and religious implications of the invention of architecture.

The jar represents the human impulse to claim and shape space, to impose order and meaning upon the chaos of the natural world. It symbolizes the division between the natural and the man-made, and the way in which human creations can alter our perception and understanding of the world around us. Just as the jar takes dominion over the wilderness, the invention of architecture during the Neolithic period forever changed the way humans perceive and interact with their environment, shaping our psychology and religious beliefs in ways that continue to resonate to this day.

The Relationship of Architecture to the Awareness of Death

The Astronomical Alignment of the Dolmen de Menga and Its Broader Significance

The astronomical alignment of the Dolmen de Menga with the summer solstice sunrise is not an isolated phenomenon, but rather part of a larger pattern of archaeoastronomical significance in Neolithic monuments across Europe and beyond. Many megalithic structures, such as Newgrange in Ireland and Maeshowe in Scotland, have been found to have precise alignments with solar and lunar events, suggesting that the ancient builders had a sophisticated understanding of the movements of celestial bodies and incorporated this knowledge into their architectural designs.

The alignment of the Dolmen de Menga with the summer solstice sunrise may have held profound symbolic and ritual significance for the Neolithic community that built and used the structure. The solstice, as a moment of transition and renewal in the natural cycle of the year, could have been associated with themes of rebirth, fertility, and the regeneration of life. The penetration of the sun’s first rays into the inner chamber of the dolmen on this date may have been seen as a sacred union between the celestial and terrestrial realms, a moment of cosmic alignment and heightened spiritual potency.

The incorporation of astronomical alignments into Neolithic monuments across Europe suggests that these ancient societies had a shared cosmological understanding and a deep reverence for the cycles of the sun, moon, and stars. The construction of megalithic structures like the Dolmen de Menga can be seen as an attempt to harmonize human activity with the larger rhythms of the cosmos, creating a sense of unity and connection between people and the natural and celestial worlds they inhabited.

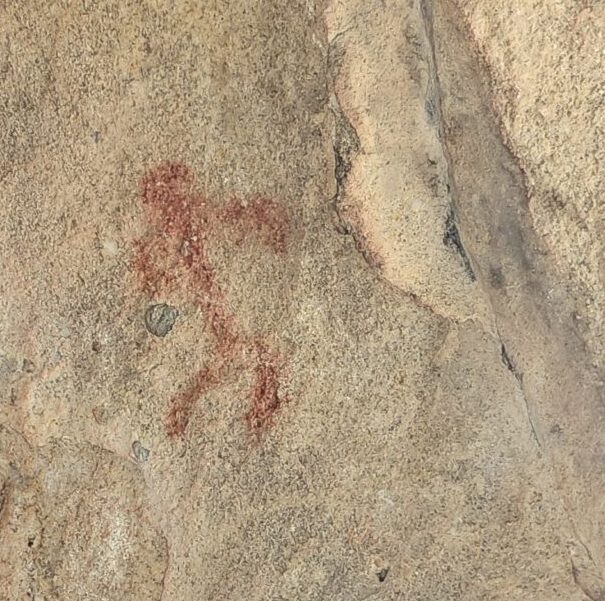

Originally these structures were probably lovingly adorned with paint and patterns. This paint was usually made of red ochre and iron oxide. We know that because the paintings that are left in Iberia are made of these materials and the extremely few neolithic portal tombs that were protected from the elements still have geographic markings.

Here is me hiking up to look at some iron oxide neolithic paintings

Here is a little guy made out of iron oxide who is about six thousand years old

The 4th millennium BC painting inside the Dolmen Anta de Antelas in Iberia

Some researchers, such as David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson, have proposed that the geometric patterns and designs found in Neolithic art and architecture may represent the visions experienced by shamans during altered states of consciousness.

Other scholars, like Michael Winkelman, argue that shamanism played a crucial role in the development of early human cognition and social organization. According to this theory, the construction of sacred spaces like the Dolmen de Menga may have been closely tied to the practices and beliefs of shaman cults, who served as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual realms.

The Imagistic and Doctrinal Modes of Religiosity: Portal Tombs as Imagistic Ritual Spaces

The cognitive anthropology of religion offers valuable insights into the different modes of religiosity and how they manifest in religious structures and practices. One key distinction is between imagistic and doctrinal modes of religiosity, as proposed by anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse. This framework can help us better understand the role and significance of Neolithic portal tombs, such as the Dolmen de Menga, in the religious life of ancient communities.

Imagistic religiosity is characterized by infrequent, highly arousing, and emotionally intense rituals that create vivid and enduring memories. These rituals often involve extreme sensory stimulation, such as loud music, dancing, or even painful ordeals. The powerful experiences generated by imagistic rituals serve to create strong social bonds and a sense of collective identity among participants.

In contrast, doctrinal religiosity involves frequent, low-arousal rituals that emphasize the transmission of complex religious teachings and doctrines. These rituals, such as regular prayers or scriptural study, aim to reinforce orthodoxy and maintain a shared belief system over time.

Applying this framework to the Dolmen de Menga and other Neolithic portal tombs, we can hypothesize that these structures were primarily used in an imagistic mode of religiosity. The infrequent and highly symbolic nature of the rituals associated with these tombs, such as the summer solstice alignment, suggests that they were designed to create intense and memorable experiences for participants.

The astronomical alignment of the Dolmen de Menga, which allows the sun’s first rays to penetrate the inner chamber on the summer solstice, could have served as a powerful sensory stimulus, evoking feelings of awe, mystery, and connection to the cosmos. The act of entering the dark, womb-like space of the tomb and witnessing the dramatic interplay of light and shadow may have induced altered states of consciousness, facilitating a sense of communion with the divine or the spirits of the ancestors.

Furthermore, the construction of portal tombs required immense collective effort and coordination, which could have fostered strong social bonds and a sense of shared purpose among the community. The participation in the building process and the subsequent rituals within these sacred spaces would have created a powerful sense of collective identity and solidarity.

The imagistic use of portal tombs can also be understood in relation to the concept of “modes of religiosity” developed by anthropologist Robert N. McCauley and cognitive scientist E. Thomas Lawson. According to their theory, imagistic rituals are more likely to be associated with “special agent rituals,” which involve direct interaction with supernatural agents, such as deities or ancestors. The dramatic and sensory-rich nature of imagistic rituals, as experienced in portal tombs, could have facilitated a sense of direct encounter with the divine, making the presence of supernatural agents more tangible and immediate.

In contrast, the doctrinal mode of religiosity, which emerged later in human history with the development of complex religious institutions and textual traditions, relies more heavily on “special instrument rituals.” These rituals involve the use of sacred objects or substances that are believed to channel divine power, but do not necessarily involve direct interaction with supernatural agents.

The shift from imagistic to doctrinal modes of religiosity can be seen as part of the broader evolution of human cognition and culture. As societies became more complex and hierarchical, the need for stable and standardized religious beliefs and practices grew, leading to the development of doctrinal traditions. However, the imagistic mode of religiosity never entirely disappeared, and continues to play a role in many contemporary religious practices, particularly those that emphasize personal experience and emotional intensity.

By understanding the Dolmen de Menga and other Neolithic portal tombs through the lens of imagistic religiosity, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the powerful experiences and social bonds that these structures facilitated. The cognitive anthropology of religion offers a valuable framework for interpreting the symbolic and experiential dimensions of these ancient monuments, shedding light on the complex interplay of architecture, ritual, and human cognition in the development of early religious traditions.

Integrating this perspective with the insights from archaeology, archaeoastronomy, and other disciplines, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of the role of portal tombs in the religious and social lives of Neolithic communities. The imagistic use of these structures highlights the importance of sensory experience, emotional arousal, and collective participation in the formation of religious beliefs and practices, and underscores the enduring power of architecture to shape human consciousness and forge deep connections between individuals, communities, and the cosmos.

As we continue to study and reflect on the significance of ancient monuments like the Dolmen de Menga, the cognitive anthropology of religion reminds us to consider not only the physical and technological aspects of these structures, but also the rich tapestry of human experiences, emotions, and beliefs that they embody. By engaging with these dimensions, we can develop a more nuanced and empathetic understanding of the religious lives of our ancestors, and gain new insights into the enduring role of architecture in the human quest for meaning, connection, and transcendence.

What is Architecture: Why did we invent it?

Philosopher, Peter Sloterdijk’s theory of spheres, particularly his concept of the first primal globe and its subsequent splitting, offers an intriguing framework for understanding the evolution of human spatial awareness and its manifestations in art and architecture. Sloterdijk’s “spherology” posits that human existence is fundamentally about creating and inhabiting spheres – protected, intimate spaces that provide both physical and psychological shelter. The “first primal globe” in his theory refers to the womb, the original protected space that humans experience. According to Sloterdijk, the trauma of birth represents a splitting of this primal sphere, leading humans to constantly seek to recreate similar protective environments throughout their lives and cultures. This concept of sphere-creation and inhabitation can be seen as a driving force behind much of human culture and architecture.

Applying this framework to Neolithic architecture like dolmens and portal tombs, we might interpret these structures as attempts to recreate protected, womb-like spaces on a larger scale. These stone structures, with their enclosed spaces and narrow entrances, could be seen as physical manifestations of the desire to recreate the security and intimacy of the “primal sphere” and our universal interaction with it through the archetype of birth.

In the Neolithic period, the world was perceived as an undifferentiated sphere, where the sacred and the secular were intimately intertwined. The concept of separate realms for the divine and the mundane had not yet emerged, and the universe was experienced as a single, all-encompassing reality. In this context, the creation of the earliest permanent architecture, such as portal tombs, represents a significant milestone in human history, marking the beginning of a fundamental shift in how humans understood and organized their environment.

Portal tombs, also known as dolmens, are among the most enigmatic and captivating architectural structures of the Neolithic era. These megalithic monuments, consisting of large upright stones supporting a massive horizontal capstone, have puzzled and intrigued researchers and visitors alike for centuries. While their exact purpose remains a subject of debate, many scholars believe that portal tombs played a crucial role in the emergence of the concept of sacred space and the demarcation of the secular and the divine.

Mircea Eliade. In his seminal work, “The Sacred and the Profane,” Eliade argues that the creation of sacred space is a fundamental aspect of human religiosity, serving to distinguish the realm of the divine from the ordinary world of everyday existence. He suggests that the construction of portal tombs and other megalithic structures in the Neolithic period represents an early attempt to create a liminal space between the sacred and the secular, a threshold where humans could encounter the numinous and connect with the spiritual realm.

Remember that this was the advent of the most basic technology, or as Slotedijik might label it, anthropotechnics. The idea that sacred and secular space could even be separated was itself a technological invention, or rather made possible because of one.

Anthropotechnics refers to the various practices, techniques, and systems humans use to shape, train, and improve themselves. It encompasses the methods by which humans attempt to modify their biological, psychological, and social conditions.

The Nature of Architecture and Its Fundamental Role in Human Life

Architecture, at its core, is more than merely the design and construction of buildings. It is a profound expression of human creativity, culture, and our relationship with the world around us. Throughout history, scholars and theorists have sought to unravel the fundamental nature of architecture and its impact on the human experience. By examining various theories and perspectives, we can gain a deeper understanding of the role that architecture plays in shaping our lives and the societies in which we live.

One of the most influential thinkers to explore the essence of architecture was the philosopher Hannah Arendt. In her work, Arendt emphasized the importance of the built environment in creating a sense of stability, permanence, and shared experience in human life. She argued that architecture serves as a tangible manifestation of the human capacity for creation and the desire to establish a lasting presence in the world.

Arendt’s ideas highlight the fundamental role that architecture plays in providing a physical framework for human existence. By creating spaces that endure over time, architecture allows us to anchor ourselves in the world and develop a sense of belonging and continuity. It serves as a backdrop against which the drama of human life unfolds, shaping our experiences, memories, and interactions with others.

Other theorists, such as Martin Heidegger and Gaston Bachelard, have explored the philosophical and psychological dimensions of architecture. Heidegger, in his essay “Building Dwelling Thinking,” argued that the act of building is intimately connected to the human experience of dwelling in the world. He suggested that architecture is not merely a matter of creating functional structures, but rather a means of establishing a meaningful relationship between individuals and their environment.

Bachelard, in his book “The Poetics of Space,” delved into the emotional and imaginative aspects of architecture. He explored how different spaces, such as homes, attics, and basements, evoke specific feelings and memories, shaping our inner lives and sense of self. Bachelard’s ideas highlight the powerful psychological impact that architecture can have on individuals, serving as a catalyst for introspection, creativity, and self-discovery.

From a sociological perspective, theorists like Henri Lefebvre and Michel Foucault have examined the ways in which architecture reflects and reinforces power structures and social hierarchies. Lefebvre, in his book “The Production of Space,” argued that architecture is not merely a neutral container for human activity, but rather a product of social, political, and economic forces. He suggested that the design and organization of space can perpetuate inequality, segregation, and control, shaping the way individuals and communities interact with one another.

Foucault, in his work on disciplinary institutions such as prisons and hospitals, explored how architecture can be used as a tool for surveillance, regulation, and the exercise of power. His ideas highlight the potential for architecture to serve as an instrument of social control, influencing behavior and shaping the lives of those who inhabit or interact with the built environment.

By engaging with the diverse theories and perspectives on architecture, we can develop a more nuanced understanding of its role in shaping the human experience. From the philosophical insights of Arendt and Heidegger to the psychological explorations of Bachelard and the sociological critiques of Lefebvre and Foucault, each perspective offers a unique lens through which to examine the essence of architecture and its impact on our lives.

As we continue to grapple with the challenges of an increasingly urbanized and globalized world, the study of architecture and its fundamental nature becomes more important than ever. By unlocking the secrets of this ancient and enduring art form, we may find new ways to create spaces that nurture the human spirit, foster connection and belonging, and shape a built environment that truly reflects our highest values and aspirations.

Violet’s Encounter with the Dolmen

It is a common misconception to think of children as blank slates, mere tabula rasas upon which culture and experience inscribe themselves. In truth, children are born with the same primal unconscious that has been part of the human psyche since prehistory. They are simply closer to this wellspring of archetypes, instincts, and imaginative potentials than most adults, who have learned to distance themselves from it through the construction of a rational, bounded ego. While I talked to the archaeologist on site of the Dolmen de Menga, I saw the that these rituals and symbols are still alive in the unconscious of modern children just as they were in the stone age. I looked at the ground to see that Violet was instinctually making a little Dolmen out of dirt.

It is a common misconception to think of children as blank slates, mere tabula rasas upon which culture and experience inscribe themselves. In truth, children are born with the same primal unconscious that has been part of the human psyche since prehistory. They are simply closer to this wellspring of archetypes, instincts, and imaginative potentials than most adults, who have learned to distance themselves from it through the construction of a rational, bounded ego. While I talked to the archaeologist on site of the Dolmen de Menga, I saw the that these rituals and symbols are still alive in the unconscious of modern children just as they were in the stone age. I looked at the ground to see that Violet was instinctually making a little Dolmen out of dirt.

My daughter Violet’s recent fear of the dark illustrates this innate connection to the primal unconscious. When she wakes up afraid in the middle of the night, I try to reassure her by explaining that the shadows that loom in the darkness are nothing more than parts of herself that she does not yet know how to understand yet or integrate. They are manifestations of the unknown, the numinous, the archetypal – all those aspects of the psyche that can be terrifying in their raw power and otherness, but that also hold the keys to creativity, transformation, and growth.

Violet intuitively understands this link between fear and creativity. She has begun using the very things that frighten her as inspiration for her storytelling and artwork, transmuting her nighttime terrors into imaginative narratives and symbols. This process of turning the raw materials of the unconscious into concrete expressions is a perfect microcosm of the way in which art and architecture have always functioned for humans – as ways of both channeling and containing the primal energies that surge within us.

When Violet walked through the Dolmen de Menga and listened to the archaeologist’s explanations of how it was built, something in her immediately responded with recognition and understanding. The dolmen’s construction – the careful arrangement of massive stones to create an enduring sacred space – made intuitive sense to her in a way that it might not for an adult more removed from the primal architect within.

I see this same impulse in Violet whenever we go to the park and she asks me where she can build something that will last forever. Her structures made of sticks and stones by the riverbank, where the groundskeepers will not disturb them, are her way of creating something permanent and visible – her own small monuments to the human drive to make a mark on the world and to shape our environment into a reflection of our inner reality.

By exploring the origins of architecture in monuments like the Dolmen de Menga, we can gain insight into the universal human impulse to create meaning, order, and beauty in the built environment. The megalithic structures of the Neolithic period represent some of the earliest and most impressive examples of human creativity and ingenuity applied to the shaping of space and the creation of enduring cultural landmarks.

Moreover, studying the astronomical alignments and symbolic significance of ancient monuments can shed light on the fundamental human desire to connect with the larger cosmos and to find our place within the grand cycles of nature and the universe. The incorporation of celestial events into the design and use of structures like the Dolmen de Menga reflects a profound awareness of the interconnectedness of human life with the wider world, a theme that continues to resonate in the art and architecture of cultures throughout history.

Here is my explorer buddy

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Anthropology

Bibliography

Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press.

Whitehouse, H. (2004). Modes of religiosity: A cognitive theory of religious transmission. Rowman Altamira.

McCauley, R. N., & Lawson, E. T. (2002). Bringing ritual to mind: Psychological foundations of cultural forms. Cambridge University Press.

Atran, S., & Henrich, J. (2010). The evolution of religion: How cognitive by-products, adaptive learning heuristics, ritual displays, and group competition generate deep commitments to prosocial religions. Biological Theory, 5(1), 18-30.

Boyer, P. (2001). Religion explained: The evolutionary origins of religious thought. Basic books.

Tremlin, T. (2010). Minds and gods: The cognitive foundations of religion. Oxford University Press.

Geertz, A. W. (2013). Origins of religion, cognition and culture. Routledge.

Pyysiäinen, I. (2009). Supernatural agents: Why we believe in souls, gods, and Buddhas. Oxford University Press.

Purzycki, B. G., & Sosis, R. (2013). The religious system as adaptive: Cognitive flexibility, public displays, and acceptance. In Biological and cultural bases of human inference (pp. 243-256). Psychology Press.

Sørensen, J. (2007). A cognitive theory of magic. Rowman Altamira.

Xygalatas, D. (2014). The burning saints: Cognition and culture in the fire-walking rituals of the Anastenaria. Routledge.

Bachelard, G. (1994). The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

Belmonte, J. A., & Hoskin, M. (2002). Reflejo del cosmos: atlas de arqueoastronomía del Mediterráneo antiguo. Equipo Sirius.

Criado-Boado, F., & Villoch-Vázquez, V. (2000). Monumentalizing landscape: from present perception to the past meaning of Galician megalithism (north-west Iberian Peninsula). European Journal of Archaeology, 3(2), 188-216.

Edinger, E. F. (1984). The Creation of Consciousness: Jung’s Myth for Modern Man. Inner City Books.

Eliade, M. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt, Brace & World.

Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage Books.

Heidegger, M. (1971). Building Dwelling Thinking. In Poetry, Language, Thought. Harper & Row.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Blackwell.

Lewis-Williams, D., & Dowson, T. A. (1988). The signs of all times: entoptic phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic art. Current Anthropology, 29(2), 201-245.

Márquez-Romero, J. E., & Jiménez-Jáimez, V. (2010). Prehistoric Enclosures in Southern Iberia (Andalusia): La Loma Del Real Tesoro (Seville, Spain) and Its Resources. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 76, 357-374.

Neumann, E. (1954). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Rappenglueck, M. A. (1998). Palaeolithic Shamanistic Cosmography: How Is the Famous Rock Picture in the Shaft of the Lascaux Grotto to be Decoded?. Artepreistorica, 5, 43-75.

Ruggles, C. L. (2015). Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. Springer.

Sloterdijk, P. (2011). Bubbles: Spheres Volume I: Microspherology. Semiotext(e).

Sloterdijk, P. (2014). Globes: Spheres Volume II: Macrospherology. Semiotext(e).

Sloterdijk, P. (2016). Foams: Spheres Volume III: Plural Spherology. Semiotext(e).

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine Publishing Company.

Winkelman, M. (2010). Shamanism: A Biopsychosocial Paradigm of Consciousness and Healing. Praeger.

Further Reading:

Belmonte, J. A. (1999). Las leyes del cielo: astronomía y civilizaciones antiguas. Temas de Hoy.

Bradley, R. (1998). The Significance of Monuments: On the Shaping of Human Experience in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe. Routledge.

Devereux, P. (2001). The Sacred Place: The Ancient Origins of Holy and Mystical Sites. Cassell & Co.

Gimbutas, M. (1989). The Language of the Goddess. Harper & Row.

Harding, A. F. (2003). European Societies in the Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press.

Hoskin, M. (2001). Tombs, Temples and Their Orientations: A New Perspective on Mediterranean Prehistory. Ocarina Books.

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge.

Norberg-Schulz, C. (1980). Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. Rizzoli.

Renfrew, C., & Bahn, P. (2016). Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice. Thames & Hudson.

Scarre, C. (2002). Monuments and Landscape in Atlantic Europe: Perception and Society During the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. Routledge.

Sherratt, A. (1995). Instruments of Conversion? The Role of Megaliths in the Mesolithic/Neolithic Transition in Northwest Europe. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 14(3), 245-260.

Tilley, C. (1994). A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Berg.

Tilley, C. (2010). Interpreting Landscapes: Geologies, Topographies, Identities. Left Coast Press.

Twohig, E. S. (1981). The Megalithic Art of Western Europe. Clarendon Press.

Watkins, A. (1925). The Old Straight Track: Its Mounds, Beacons, Moats, Sites, and Mark Stones. Methuen.

Whittle, A. (1996). Europe in the Neolithic: The Creation of New Worlds. Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, P. J. (1988). The Domestication of the Human Species. Yale University Press.

Zubrow, E. B. W. (1994). Cognitive Archaeology Reconsidered. In The Ancient Mind: Elements of Cognitive Archaeology. Cambridge University Press.

Zvelebil, M. (1986). Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies of Temperate Eurasia and Their Transition to Farming. Cambridge University Press.

Zvelebil, M., & Jordan, P. (1999). Hunter-Fisher-Gatherer Ritual Landscapes: Spatial Organisation, Social Structure and Ideology Among Hunter-Gatherers of Northern Europe and Western Siberia. Archaeopress.

Jungian Innovators

Topics

How do Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality Intersect?

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jungian Thought to Combat Addiction

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Jungian Analysts

Mythology, Anthro, Evopsych, Comparative Religion

Mystics, Philosophers and Gurus

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite

Spirituality

0 Comments