She’s sitting there holding the baby, but she’s gone. The person you love has disappeared into a hollow shell going through the motions of motherhood. She smiles for photos, but her eyes are empty. She says she’s fine, but you watch her hands shake as she prepares another bottle. She insists she’s just tired, but you know this is something deeper, darker, more dangerous than exhaustion.

Or maybe you’re watching him fall apart in ways no one talks about. Your partner who was so excited to be a dad now can’t get out of bed. He says he feels nothing when he holds the baby. He’s angry all the time, or numb, or both. But when you Google “postpartum depression,” all you see are pictures of crying mothers. No one talks about paternal postpartum depression, but it’s destroying your family just the same.

Postpartum depression is not the “baby blues.” It’s not something that resolves with a good night’s sleep or a spa day. It’s a serious mental health condition that affects 10-20% of new mothers and up to 10% of new fathers. It can range from persistent sadness and anxiety to complete disconnection from reality. And despite what Instagram would have you believe, it has nothing to do with how much someone loves their baby or how good a parent they are.

The tragedy is that we know how to treat postpartum depression. We have therapies that work, medications that are safe for breastfeeding, support systems that can help. But shame, stigma, and systemic failures mean most people with PPD never get help. They suffer in silence, convinced they’re failing at the one thing they’re supposed to naturally know how to do.

Understanding Postpartum Depression

Let’s start with what postpartum depression actually is, beyond the sanitized version presented in pamphlets at the OB’s office. PPD is what happens when the perfect storm of hormonal changes, sleep deprivation, identity upheaval, and often trauma collide in a nervous system that’s already depleted from growing and delivering a human being.

The hormone crash after delivery is like nothing else the human body experiences. Estrogen and progesterone levels plummet from their pregnancy peaks to below pre-pregnancy levels within hours of delivery. For context, this is a more dramatic hormonal shift than menopause, which happens gradually over years. Some people’s brains weather this crash fine. Others go into complete dysregulation.

Add to this the thyroid disruption that’s common postpartum. The oxytocin paradox where the “love hormone” can actually increase anxiety in some people. The prolactin elevations from breastfeeding that can affect mood. The cortisol dysregulation from chronic sleep deprivation. It’s a neurochemical perfect storm, and we expect people to just power through it.

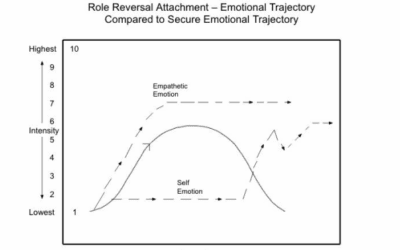

But PPD isn’t just biological. It’s the psychological annihilation of who you were before. The career-driven woman who now can’t remember what day it is. The person who prided themselves on independence now unable to shower without help. The couple who were partners now strangers ships passing in the night, arguing about whose turn it is to deal with the screaming.

There’s often trauma that no one acknowledges. Birth trauma is real – emergency C-sections, hemorrhaging, NICU stays, births that didn’t go according to plan. The body remembers even if everyone tells you “all that matters is a healthy baby.” Breastfeeding trauma from cracked nipples, mastitis, babies who won’t latch, the shame of formula feeding in a “breast is best” culture.

Risk factors for PPD read like a checklist of modern motherhood: history of depression or anxiety, lack of social support, financial stress, relationship problems, difficult pregnancy or delivery, baby with health issues, unplanned pregnancy. But even people with zero risk factors can develop PPD. That’s what makes it so insidious – it can happen to anyone.

The symptoms go far beyond sadness. Yes, there’s often persistent depression, but there’s also rage that comes out of nowhere. Intrusive thoughts about harm coming to the baby. Anxiety so severe it prevents sleep even when the baby is sleeping. Disconnection from the baby, feeling like you’re babysitting someone else’s child. Obsessive thoughts about the baby’s safety. Feeling like your family would be better off without you.

These symptoms are terrifying when you’re experiencing them. The intrusive thoughts especially – imagining dropping the baby, drowning them during bath time, terrible things happening to them. These thoughts don’t mean someone wants to hurt their baby. They’re actually a sign of how much the person cares, how terrified they are of something happening. But without understanding this, parents suffer in silent horror, convinced they’re monsters.

What NOT to Say or Do

Let’s talk about all the well-meaning things people say that actually make postpartum depression worse. These phrases usually come from love and concern, but they land like daggers in the heart of someone already drowning in shame.

“Sleep when the baby sleeps” might be the most useless advice ever given. First, it assumes the baby actually sleeps. Second, it ignores that anxiety and depression affect sleep. Someone with PPD might be physically exhausted but unable to turn off their racing thoughts. They lie there while the baby naps, heart pounding, mind spinning, hating themselves for wasting this precious sleep opportunity.

“Enjoy every moment” or “They’re only little once” is toxic positivity at its finest. Someone with PPD might not be enjoying any moments. They might be counting the minutes until bedtime, then feeling guilty for wishing time away. Being told to enjoy something you’re finding torturous adds shame to an already unbearable situation.

“Breast is best” or any feeding pressure needs to stop immediately. For someone with PPD, breastfeeding might be a trigger for anxiety, panic, or dissociation. Their mental health is more important than breast milk. A fed baby with a mentally healthy parent is better than a breastfed baby with a parent in crisis. Full stop.

“At least you have a healthy baby” minimizes everything the parent is experiencing. Yes, they’re grateful for a healthy baby. They’re also drowning. Both things can be true. This phrase suggests they shouldn’t be struggling if the baby is okay, adding guilt to their already overwhelming emotional load.

“You don’t look depressed” or “But you’re doing such a great job” invalidates their internal experience. People with PPD often become expert performers, showing the world what it expects to see while dying inside. Just because someone manages to shower and smile for a photo doesn’t mean they’re not in crisis.

“Have you tried [yoga/vitamins/essential oils/prayer]?” implies that PPD is a lifestyle problem with a simple solution. While these things might help as additions to proper treatment, suggesting them as solutions minimizes the severity of PPD and implies the person just isn’t trying hard enough to feel better.

“I know how you feel, I was tired too” or any comparison to normal new parent exhaustion misses the point entirely. PPD isn’t just being tired. It’s being unable to feel joy, connection, or hope. It’s your brain telling you your family would be better off without you. It’s not the same as normal new parent struggles, and pretending it is leaves people feeling even more isolated.

“What do you have to be depressed about?” reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of depression. PPD doesn’t need a reason. You can have a supportive partner, healthy baby, financial stability, and still have PPD. It’s not about circumstances; it’s about brain chemistry and psychological factors beyond conscious control.

Don’t take over without permission. Swooping in to “help” by rearranging their home, taking the baby without asking, or making decisions for them can increase feelings of inadequacy and loss of control. What feels like help to you might feel like judgment to someone with PPD – confirmation that they’re failing and need rescuing.

Don’t minimize medication needs. Comments like “You don’t want to take drugs while breastfeeding” or “Medication is a last resort” can prevent people from getting lifesaving treatment. Many medications are safe for breastfeeding, and even if they weren’t, a parent’s mental health is crucial for baby’s wellbeing.

Practical Support Strategies

Real support for someone with PPD means showing up consistently with concrete help, not platitudes or advice. It means taking tasks off their plate without them having to ask, explain, or feel guilty. It means creating safety and stability while they navigate this storm.

Immediate needs must be addressed first. Sleep deprivation exacerbates every symptom of PPD. If you can take night duty even once a week so they can get uninterrupted sleep, do it. Not “call me if you need me” but “I’m coming Wednesday nights to do all night feeds.” Bring pumped milk or formula. Let them sleep in a different room where they can’t hear the baby. Guard that sleep fiercely.

Nutrition becomes impossible when you’re in survival mode. Bring food that’s ready to eat – not ingredients for them to cook. Cut-up fruit, protein bars, smoothies, sandwiches. Foods they can eat one-handed while holding a baby. Set up a snack station within reach of where they nurse or pump. Hydration too – fill water bottles, bring electrolyte drinks, make sure they’re drinking.

Hygiene and basic self-care become monumentally difficult with PPD. Offer to hold the baby so they can take an actual shower, not a rushed rinse. Wash their hair. Change their sheets. Do laundry without asking. These aren’t luxuries; they’re human needs that become impossible when you’re drowning.

Emotional support requires presence without pressure. Sit with them without expecting conversation. Let them cry without trying to fix it. Listen without offering solutions. Sometimes the most powerful thing you can say is “This is really fucking hard, and you’re not imagining it.” Validation of their struggle is more healing than any advice.

When they express dark thoughts – “I’m a terrible mother,” “My family would be better off without me” – don’t argue or reassure. Instead, reflect and explore: “It sounds like you’re in so much pain right now. Can you tell me more about these feelings?” Take all mentions of self-harm seriously, even if they seem offhand. Better to overreact than miss a crisis.

Household management needs to be taken over, not “helped with.” Don’t ask “What can I do?” because decision fatigue is real and they might not know. Just do. Dishes, laundry, tidying, pet care, paying bills if you’re close enough for that. Handle the logistics of life so they can focus on surviving.

Baby care support should respect their relationship with the baby while providing relief. Don’t swoop in like you’re rescuing the baby from them. Instead: “I’d love to walk the baby in the stroller so you can rest/shower/eat.” Hold the baby during their fussy period so the parent can have a break from crying. But also support bonding – sit with them during feeds, tell them what a good job they’re doing, notice small victories.

Professional help facilitation is crucial. Research therapists who specialize in PPD. Make appointments (with their permission). Offer to drive them or babysit during appointments. Help with insurance calls. If they’re resistant, frame it as “checking in with someone who specializes in postpartum adjustment” rather than “you need therapy.”

Different Therapeutic Approaches for PPD

Postpartum depression requires specialized treatment that addresses both the unique biological factors and the psychological challenges of new parenthood. Not all therapy is created equal when it comes to PPD – you need someone who understands the postpartum period, not just depression in general.

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) is specifically adapted for postpartum depression and focuses on the relationship changes and role transitions that come with parenthood. IPT recognizes that PPD happens in a relational context – the relationship with the baby, the partner, extended family, and oneself all shift dramatically with parenthood.

In IPT, you might explore the grief of losing your pre-parent identity. The rage at your partner who seems unchanged while your entire existence has been upended. The complicated feelings toward a baby you desperately wanted but now feel trapped by. The isolation from friends who don’t have kids. These aren’t character flaws – they’re normal responses to massive life changes that deserve therapeutic attention.

CBT for PPD has specific protocols that address the unique cognitive patterns of postpartum depression. The thoughts aren’t just negative – they’re specifically about being a bad mother, failing the baby, ruining the child’s life. CBT helps identify and challenge these postpartum-specific distortions while building practical coping skills for the demands of early parenthood.

But CBT for PPD also needs to be realistic. Some negative thoughts might be based in reality – maybe breastfeeding really isn’t working, maybe the partner really isn’t pulling their weight. Good PPD therapy validates real challenges while helping differentiate between depression’s lies and actual problems that need addressing.

EMDR for birth trauma is increasingly recognized as crucial for PPD treatment. Many people with PPD have traumatic births that are never processed. The emergency C-section where they thought they’d die. The NICU stay where they couldn’t hold their baby. The moment they were told something was wrong. These traumas get stuck, replaying every time they look at their baby.

EMDR can process these traumatic memories without requiring detailed verbal processing, which is important when someone is too exhausted or dissociated to do traditional trauma work. The bilateral stimulation helps the brain integrate the trauma so it stops hijacking the present moment. Many people find their PPD symptoms significantly improve once birth trauma is resolved.

Somatic work addresses how PPD lives in the body. The chest that won’t fully expand. The shoulders constantly braced for crisis. The disconnection from a body that feels foreign after pregnancy and birth. Somatic therapy helps rebuild the mind-body connection that pregnancy, birth, and postpartum challenges often sever.

This might include gentle movement, breathwork, or simply learning to notice body sensations without judgment. For someone who dissociates during feeding or feels disconnected from their postpartum body, somatic work can be grounding and reconnecting.

Group therapy specifically for PPD provides something individual therapy can’t – the knowledge that you’re not alone, you’re not the only one struggling, you’re not the worst mother in the world. Hearing other parents express the same dark thoughts, the same disconnection, the same rage, normalizes experiences that feel shamefully abnormal.

PPD groups also provide practical strategies from people actually living it. The mom who figured out how to manage intrusive thoughts. The dad who found ways to bond with a baby he felt nothing for. These peer strategies sometimes land better than professional advice because they come from people in the trenches.

Medication considerations for PPD are complex and require a psychiatrist familiar with postpartum issues. SSRIs are often first-line treatment and many are compatible with breastfeeding. Sertraline (Zoloft) in particular has extensive safety data for breastfeeding. But medication isn’t one-size-fits-all – what works for one person might not for another.

There’s also Brexanolone (Zulresso), the first FDA-approved medication specifically for PPD, given as an IV infusion over 60 hours. It works faster than traditional antidepressants but requires hospitalization. Newer options like Zuranolone (Zurzuvae) offer similar benefits in oral form. These medications work on GABA receptors, addressing the specific neurochemical disruptions of PPD.

The key is finding a psychiatrist who won’t just throw medications at symptoms but will consider the whole picture – breastfeeding goals, sleep deprivation, hormonal factors, previous medication responses. Someone who understands that “start low and go slow” is especially important when someone is already managing a newborn.

Partners’ Mental Health Matters Too

We need to talk about paternal postpartum depression because pretending it doesn’t exist is killing fathers and destroying families. Up to 10% of new fathers experience PPD, but it’s rarely screened for, rarely discussed, and rarely treated. Men are told to “man up,” to be strong for their partner, to be grateful they don’t have to physically recover from birth.

Paternal PPD often looks different from maternal PPD. Less crying, more anger. Less sadness, more numbness. Less obvious depression, more working late to avoid home. Men might throw themselves into work, develop substance issues, have affairs, or rage at small frustrations. These behaviors get labeled as men being assholes rather than recognized as depression symptoms.

The risk factors for paternal PPD include partner’s PPD (up to 50% of partners of women with PPD develop it themselves), financial stress, unplanned pregnancy, relationship problems, and lack of social support. But the biggest risk factor might be the complete invisibility of paternal mental health in the postpartum period.

Fathers often feel profoundly disconnected from a baby they didn’t carry, can’t breastfeed, and might not have wanted. They watch their partner become consumed by the baby while they become invisible except as a paycheck and occasional babysitter. They lose their partner, their sex life, their freedom, their identity, and they’re supposed to be happy about it.

Caregiver burnout affects whoever is doing the caregiving, regardless of gender or biological connection to the baby. If you’re the primary caregiver while your partner has PPD, you’re essentially single parenting while also managing a mental health crisis. If you’re both struggling with PPD, you’re drowning together with no one to throw a life preserver.

Couples therapy might be essential when PPD affects the relationship. And it always affects the relationship. The resentment, the disconnection, the complete absence of intimacy, the parallel lives instead of partnership. A couples therapist who understands PPD can help navigate this without blame, recognizing that PPD is attacking the relationship, not that either partner is failing.

Creating a Postpartum Support Plan

The time to plan for postpartum mental health is before birth, not in crisis. Every pregnant person should have a postpartum mental health plan as detailed as their birth plan. Yet most people spend more time choosing a stroller than preparing for potential PPD.

Before birth preparation includes identifying risk factors, lining up support systems, and finding providers. If there’s a history of depression or anxiety, get connected with a perinatal psychiatrist before delivery. Have therapist options researched. Know which friends will actually help versus those who’ll just want to hold the baby.

Create a “warning signs” document that lists specific symptoms that would indicate professional help is needed. Share this with partners, close friends, and family. Include things like: persistent crying, inability to sleep when baby sleeps, intrusive thoughts, disconnection from baby, thoughts of self-harm. Give people permission to intervene if they see these signs.

Set up practical support in advance. Meal trains, night doulas, postpartum doulas, cleaning services. Yes, these cost money, but treating full-blown PPD costs more – financially, emotionally, relationally. If budget is tight, ask for these services as baby shower gifts instead of another outfit the baby will wear once.

Warning sign agreements with partners are crucial. Agree in advance that if either of you shows signs of PPD, you’ll seek help without argument. Remove the negotiation from the equation. Make it automatic: symptoms appear, help is sought. This protects against the impaired judgment that comes with PPD.

Professional team assembly should happen before crisis. Interview therapists while pregnant. Meet with a psychiatrist to discuss medication options if PPD develops. Find a support group and maybe even attend before birth. Having these connections established makes it much more likely you’ll use them if needed.

Emergency protocols need to be explicit. If someone expresses suicidal thoughts, what happens? Who gets called? Where’s the nearest emergency room? What about the baby during a crisis? These conversations are hard but necessary. PPD can escalate quickly, and having a plan can save lives.

Include postpartum psychosis awareness in emergency planning. It’s rare (1-2 per 1000 births) but it’s a medical emergency. Symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, confusion, and rapid mood swings. It typically onset within two weeks of delivery. Anyone with bipolar disorder or previous postpartum psychosis is at higher risk. This isn’t something to handle at home – it requires immediate hospitalization.

Removing Barriers to PPD Treatment in Alabama

Let’s address the elephant in the room: accessing mental health care with a newborn is fucking difficult even without PPD. With PPD, it can feel impossible. The logistics alone – finding childcare, timing around feeds, having the executive function to make appointments – can be insurmountable barriers.

BCBS perinatal mental health coverage has expanded in recent years. Most plans now cover mental health visits for PPD under regular mental health benefits. Some plans have specific perinatal mental health programs with additional support. Call and ask specifically about perinatal mental health benefits – sometimes there are resources available that aren’t widely advertised.

Sliding scale for new families facing financial stress is crucial. Babies are expensive. If someone has unpaid maternity leave, medical bills from delivery, and suddenly needs therapy and possibly medication, the financial burden is overwhelming. Many therapists who specialize in PPD reserve sliding scale spots specifically for new parents because they understand this reality.

When asking about sliding scale, be specific: “I’m a new parent dealing with postpartum depression and finances are tight.” Many therapists who might not offer sliding scale generally will make exceptions for PPD because they understand it’s a time-limited crisis that needs immediate intervention.

Telehealth for new moms who can’t leave home has been revolutionary for PPD treatment. No need to find childcare. No need to get yourself and baby dressed and out the door. You can do therapy while the baby naps on your chest. You can breastfeed during session if needed. The barrier to entry is so much lower.

BCBS covers telehealth for mental health the same as in-person visits in most plans. This opens up access to specialists who might not be in your immediate area. If the only PPD specialist in your area has a six-month waitlist, you can see someone elsewhere in Alabama via telehealth and get help now.

The importance of immediate intervention can’t be overstated. PPD is not something that gets better with time. Without treatment, it can last years and affect the child’s development, the couple’s relationship, and the parent’s long-term mental health. Every week of untreated PPD is a week of unnecessary suffering and potential long-term consequences.

This is why PPD treatment is essential healthcare, not luxury. It’s not self-care or pampering. It’s medical treatment for a serious condition that affects the entire family system. When we frame it this way – as necessary medical care rather than optional support – it becomes easier to prioritize and access.

Community resources beyond traditional therapy can provide wraparound support. Postpartum Support International has a helpline (1-800-PPD-MOMS) and online support groups. La Leche League, despite its breastfeeding focus, often provides emotional support for struggling parents. Some churches have new parent support groups that address mental health alongside spiritual support.

New parent support groups, even those not specifically for PPD, can prevent isolation and normalize struggle. Sometimes just hearing that other parents also fantasize about running away, also regret having kids sometimes, also feel like they’re failing, provides enough relief to keep going.

The bottom line is this: PPD is common, treatable, and not a character flaw. It’s not about not loving your baby enough or not being grateful enough or not trying hard enough. It’s a medical condition that requires and deserves treatment. The parent you love is still in there, buried under the weight of depression, anxiety, and shame. With proper support and treatment, they can find their way back to themselves and to you.

If you’re reading this because someone you love has PPD, know that your support matters more than you might realize. Every meal you bring, every hour of sleep you provide, every moment of non-judgmental presence is a lifeline. You can’t fix PPD, but you can hold space for healing to happen.

If you’re reading this because you have PPD, please know: this is not your fault. You are not a bad parent. You are not broken beyond repair. This will not last forever. Help exists. You deserve support. Your family needs you alive and healing more than they need you perfect and suffering. Reach out. Keep reaching out until someone helps. You matter. Your mental health matters. You’re worth saving.

0 Comments