What Schools of Thought did Carl Jung Influence?

When Carl Jung began developing his theories of the psyche in the early 20th century, he likely did not foresee just how far his ideas would reach. As a psychoanalyst and philosopher, Jung was primarily focused on understanding the human mind and our inner worlds. Yet his groundbreaking concepts like the collective unconscious, archetypes, and the process of individuation ended up sowing seeds of insight that would sprout up far beyond the realm of psychology.

Jung was such an original and visionary thinker that his work ended up transforming fields he never explicitly addressed – from art and literature to anthropology and politics. His notions resonated so deeply that they seeped into the zeitgeist, subtly but powerfully shaping how we think about not just our own minds, but also culture, creativity, spirituality, and what it means to be human. Jung’s thought was like a stone dropped in a pond, the ripples expanding ever outward.

So how did Jung’s psychological theories come to influence so many seemingly unrelated areas? A major factor was the sheer universality and symbolic power of his ideas. Jung’s vision of a collective unconscious – a deep stratum of the mind harboring primordial images shared by all humans – lent itself to much wider application. If, as Jung proposed, all human psyches contained fundamental patterns or archetypes, then wouldn’t these same symbolic structures be expressed not just in an individual’s dreams or behaviors, but in art, literature, religion, and societies as well?

Jung’s focus on the numinous and the mythological also made his psychology ripe for a broader cultural impact. He saw the psyche as inherently spiritual, and felt that modern humans deeply needed a reconnection to the sense of meaning and mystery that myths and religion traditionally provided. This almost romantic view made Jung’s ideas highly appealing to artists, writers and thinkers who felt alienated by the rationalism and materialism of the modern world.

Additionally, Jung himself applied his theories to topics beyond individual psychology, writing about their implications for society, religion, creativity and more. His book Psychological Types introduced the hugely influential (some would say overly reductive) concepts of introversion and extraversion, which would shape personality testing for decades to come. Essays like “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry” or “Psychology and Literature” brought Jungian analysis to bear on creativity and the arts. So Jung helped set an example of how his ideas could illuminate other fields.

However, the precise nature of Jung’s impact on other disciplines is often indirect, filtered through intermediary figures, movements, and historical shifts. Tracing the influence of Jungian thought reveals a fascinating web of cross-pollination between psychology, art, culture, politics and spirituality throughout the 20th century. Let’s untangle some of those connecting threads to see just how far Jung’s ideals really spread.

Joseph Campbell and the Monomyth

One of the most direct lines of Jungian influence outside psychology runs through Joseph Campbell, the famed comparative mythologist and author of the seminal 1949 book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Campbell was deeply inspired by Jung’s ideas of the collective unconscious and archetypes. He came to see myths from around the world as expressions of the same fundamental psychological patterns – a “monomyth” or universal hero’s journey that resonated across all cultures.

Campbell framed the hero’s journey explicitly in Jungian terms, as a symbolic voyage into the unconscious and a process individuation. The hero descends into the underworld (the unconscious), confronts dragons (their shadow), and returns transformed. Campbell even believed that Jung had undergone his own mythic underworld journey during his intense visionary period following his split with Freud.

While Campbell helped popularize Jungian ideas, by his later years he began to downplay these influences, claiming the monomyth came more from his reading of Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake. Still, the monomyth is inseparable from Jungian underpinnings. Campbell also shared Jung’s view of a psyche-centric spirituality, seeing myths and religion more as metaphors for psychological growth than literal external realities.

Campbell’s monomyth model soon began shaping modern storytelling, especially screenwriting. Writers like Christopher Vogler elaborated Campbell’s ideas into a rigid script structure: the Hero’s Journey. Soon Hollywood was cranking out blockbusters explicitly built on Campbell’s template, from Star Wars to The Lion King. George Lucas cited Campbell as a key influence. The hero’s journey formula, for better or worse, still dominates much mainstream screenwriting, an enduring sign of Jung’s underlying impact.

Psychology: Actualizing Jung’s Vision

Parts-Based Therapy: Uniting Jung and Gestalt

One of the most direct applications of Jungian ideas in contemporary psychotherapy has been the development of parts-based or multiplicity models of the psyche. These approaches view the mind not as a monolithic entity, but as a dynamic system of relatively autonomous sub-personalities or “parts.”

The origins of this perspective can be traced back to Jung’s theory of complexes – emotionally charged clusters of ideas and images that can take on a life of their own within the psyche. Jung observed that complexes often behaved like independent beings, with their own agendas and characteristic modes of expression.

In many ways, complexes could be seen as the building blocks of Jung’s archetypal theory. Archetypes, after all, are essentially universal patterns or templates that structure human experience – from the nurturing Mother to the wise Old Man. When an archetype is activated in an individual’s life, it often expresses itself through a complex – a personalized manifestation of the universal theme.

Jung’s model of a “plural psyche” was given new life in the 1970s and 80s, through the work of innovative therapists like Richard Schwartz, Hal and Sidra Stone, and Arnold Mindell. These clinicians sought to integrate Jungian ideas with the experiential techniques of Gestalt Therapy, a humanistic approach developed by Fritz Perls.

Gestalt Therapy emphasized the importance of direct, “here-and-now” engagement with one’s present experience. Through techniques like dialogue, role-playing, and exaggeration, Perls encouraged clients to fully embody and express the different aspects of their psyche. The goal was to bring unconscious conflicts and polarities into awareness, so they could be integrated into a more coherent whole.

For Schwartz, the creator of Internal Family Systems (IFS) Therapy, this experiential approach was the perfect complement to Jung’s model of the psyche. In IFS, the different parts of the mind are treated as distinct personalities, each with its own unique perspective, feelings, and coping strategies. These parts often come into conflict with each other, leading to inner turmoil and dysfunction.

The goal of IFS is not to eliminate or suppress these parts, but to help them work together in harmony. The therapist guides the client in developing a relationship of curiosity and compassion towards their parts, seeing each as a valuable ally with an important role to play. Through techniques like inner dialogue and role-playing, the client learns to listen to each part’s concerns and help them find more positive ways of interacting.

A key insight of IFS is that beneath the surface level of conflicting parts lies a core Self – a source of calm, clarity, and wisdom that can act as an inner leader. This Self is not another part, but the ground of being from which all the parts emerge. In Jungian terms, it could be seen as the ego-Self axis – the connection between the conscious “I” and the deeper, transpersonal center of the psyche.

Other parts-based models, like the Voice Dialogue approach of Hal and Sidra Stone, place greater emphasis on the archetypal dimensions of the parts. The Stones see the psyche as a rich cast of characters, from the nurturing Mother to the adventurous Warrior to the mischievous Trickster. By engaging these figures directly through dialogue and embodiment, the client can tap into their unique energies and gifts.

Similarly, Arnold Mindell’s Process-Oriented Psychology views the parts as “dream figures” that appear not only in sleep, but in waking life as well. For Mindell, symptoms, conflicts, and synchronicities are all manifestations of the deeper “dreambody” – the unified field of psyche and soma. By following the unfolding process of these experiences with an attitude of open curiosity, the client can discover the hidden meanings and potentials they hold.

What all these approaches share is a commitment to honoring the diverse voices within the psyche, and creating a space for their direct, experiential expression. They represent a kind of “depth psychology of multiplicity,” uniting Jung’s vision of the archetypal depths with the Gestalt emphasis on here-and-now awareness.

Of course, parts-based models are not without their critics. Some argue that they risk reifying or pathologizing normal aspects of human diversity. Others worry that they may encourage a kind of internal dissociation or fragmentation, rather than true integration.

But at their best, these approaches offer a powerful way to work with the complex, multifaceted nature of the psyche. They remind us that we are not just one thing, but contain multitudes – a rich inner world of voices, figures, and potentials waiting to be explored.

And as we navigate the challenges of an increasingly uncertain world, this capacity for inner diversity and dialogue may be more important than ever. In learning to honor and integrate the many parts of ourselves, we may discover a new kind of wholeness – one that can embrace difference and change with creativity and grace.

So while parts-based therapy may seem like a recent innovation, its roots go back to the very beginnings of depth psychology. From Jung’s early studies of complexes and archetypes to the experiential explorations of Gestalt, the idea of a plural psyche has been a central theme in the history of dynamic therapies.

Humanistic Psychology

In the mid-20th century, a new movement began to take shape in American psychology. Spearheaded by luminaries like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, Humanistic Psychology sought to offer a more hopeful, growth-oriented alternative to the deterministic models of psychoanalysis and behaviorism that dominated at the time.

At the heart of the humanistic approach was a fundamentally optimistic view of human nature. Rogers and Maslow believed that people were inherently driven towards self-actualization – the realization of their fullest potential as unique individuals. This stood in stark contrast to Freud’s focus on psychopathology and repressed instincts, or Skinner’s view of humans as blank slates shaped by external reinforcement.

While the humanists didn’t directly adopt Jung’s more esoteric ideas like the collective unconscious or archetypes, their emphasis on growth, creativity, and the exploration of meaning and values clearly echoed themes from his work. Jung’s concept of individuation – the lifelong journey towards wholeness and self-realization – was a clear precursor to humanistic notions of self-actualization.

Indeed, Jung’s entire project could be seen as an effort to map the contours of the fully realized human life. Through his work with patients, his deep dives into mythology and religion, and his own creative and visionary practices, Jung was ultimately seeking to understand how people could become most fully themselves – how they could integrate the conscious and unconscious aspects of their psyche into a harmonious, individuated whole.

This holistic, almost romantic view of the human quest for meaning and wholeness resonated deeply with the humanistic ethos. While Rogers and Maslow placed greater emphasis on the conscious ego and interpersonal relationships than Jung did, they shared his fundamental conviction that the psyche contained vast untapped potentials waiting to be actualized.

So although the connections weren’t always explicit, Humanistic Psychology could be seen as an effort to translate Jung’s often esoteric and complex ideas into a more accessible, pragmatic form. By focusing on concepts like creativity, love, and peak experiences, the humanists helped democratize the Jungian vision of psychological growth and bring its insights to a wider audience.

Transpersonal Psychology: Exploring the Farther Reaches of Inner Space

If Humanistic Psychology represented a partial secularization of Jung’s ideas, Transpersonal Psychology took them in the opposite direction – into the realms of spirituality and altered states of consciousness.

Emerging in the late 1960s, against the backdrop of the counterculture and the human potential movement, Transpersonal Psychology sought to expand the boundaries of psychological inquiry to include the farthest reaches of human experience – from mystical states and psychedelic visions to encounters with the divine.

Central to the transpersonal project was an expanded cartography of the psyche. Drawing heavily on Jung’s model of the unconscious, transpersonal thinkers like Stanislav Grof and Ken Wilber proposed that beneath the personal and collective layers of the unconscious lay even deeper dimensions – the perinatal, corresponding to memories of birth and prenatal existence, and the transpersonal proper, a realm of pure consciousness and spiritual archetypes.

For Grof, who conducted extensive research on the therapeutic use of LSD and other psychedelics, these deeper layers of the psyche could be accessed through non-ordinary states of consciousness. Just as dreams and visions provided a royal road to the Jungian unconscious, Grof believed that psychedelics, breathwork, and other experiential techniques could open portals to the transpersonal depths.

In many ways, this represented a radical extension of Jung’s own cartography. While Jung had hinted at the existence of a layer of the psyche that transcended the individual – what he called the “psychoid” level, where mind and matter became indistinguishable – he remained primarily focused on the personal and archetypal dimensions in his therapeutic work.

The transpersonalists, by contrast, saw engagement with these farther reaches of inner space as central to the process of growth and self-realization. For them, traditional psychology’s focus on the ego and its adaptations was a necessary but insufficient step on the path to wholeness. True individuation required a kind of ego-transcendence, a willingness to let go of the narrow confines of the self and open to the wider dimensions of the cosmos.

At the same time, the transpersonalists also sought to integrate these expansive visions with the insights of modern psychology and science. Ken Wilber’s ambitious Integral Theory, for instance, aimed to create a comprehensive framework uniting the truths of premodern spirituality, modern empiricism, and postmodern relativism.

In this sense, the transpersonal project could be seen as an attempt to realize the full scope of Jung’s vision – to create a truly “depth psychology” that encompassed the entire spectrum of human consciousness, from the personal shadows to the cosmic Self.

Of course, transpersonal ideas have also sometimes veered into the realm of the speculative and the New Age, leading to charges of “psychobabble” and pseudo-science. The challenge for contemporary transpersonal thinkers is to ground their expanded maps in rigorous research and critical thinking, while still honoring the transformative power of exceptional human experiences.

But whatever their ultimate validity, there’s no denying that transpersonal concepts have exerted a profound influence on contemporary spirituality and self-help culture. From mindfulness and yoga to ayahuasca and eco-psychology, practices and ideas that were once the province of esoteric circles have now entered the mainstream – thanks in large part to the popularizing influence of the transpersonal movement.

In this sense, Transpersonal Psychology could be seen as the most direct heir to the Jungian legacy – an attempt to midwife a new “map of the soul” for a world in the throes of spiritual emergency and transformation. As we grapple with the planetary crises of our time, this expanded vision of the psyche may prove more relevant than ever – reminding us of the vast inner resources we have yet to tap in the quest for healing and wholeness.

Jung and Postmodern Philosophy

Though Jung is often portrayed as a mystic at odds with modern thought, his work anticipated and shaped several key postmodern philosophical trends. Jung’s critique of rationality and his vision of the psyche as decentered and polysemous meshed well with the post-structuralist thought of Derrida and Deleuze. For these thinkers, as for Jung, meaning was inherently unstable, and the self was more a fluid multiplicity than a fixed, bounded individual.

Jung also prefigured the postmodern fascination with the “Other” in his insistence that we each had an unconscious shadow side, and that engaging with the foreign “not-I” was crucial for growth. Postmodern and post-colonial thinkers expanded this to a cultural and political key, examining how societies projected their own shadows onto marginalized or conquered groups.

Jung’s influence also reached postmodern thought through intermediary figures like the physicist Wolfgang Pauli and the philosopher Jean Gebser. Pauli collaborated with Jung on the concept of synchronicity and helped disseminate his ideas within intellectual circles. Gebser’s evolutionary model of consciousness, moving from archaic to magical to mythical to mental-rational structures, bore clear similarities to Jung’s stages of psychic development, and shaped later integral thinkers like Wilber.

Architecture and Spatial Symbolism

Jung’s ideas about archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the psychological resonance of symbols also had a significant, if indirect, impact on architectural thought and practice in the 20th century.

One key figure in this chain of influence was Rudolf Steiner, the Austrian philosopher and esotericist whose work deeply intersected with Jung’s interest in spirituality, symbolism, and the inner life. Steiner was the founder of anthroposophy, a spiritual-scientific movement that sought to integrate modern science with mystical and artistic sensibilities.

Steiner’s architectural projects, such as the first and second Goetheanum buildings in Dornach, Switzerland, embodied an explicitly spiritual and archetypal approach to form and space. With their sculptural, organic forms and symbolic ornamentation, Steiner’s designs aimed to create environments that would speak directly to the unconscious mind and evoke transcendent experiences in the viewer.

While Steiner was not a direct student of Jung, his integration of Jungian themes like archetypes and the collective unconscious into built form helped pave the way for later currents in archetypal and symbolic architecture. Architects influenced by anthroposophy, such as Erik Asmussen and Imre Makovecz, continued to explore how buildings could embody spiritual and psychological meanings.

Another key link in the chain from Jung to architecture was Mircea Eliade, the influential Romanian scholar of religion whose work on sacred spaces, myths, and symbols deeply reflected Jungian ideas. In books like The Sacred and the Profane (1957), Eliade analyzed the archetypal structure of sacred spaces across cultures.

Eliade argued that sacred architecture served to create a channel of communication between the earthly and divine realms, an “axis mundi” or world axis around which human life could orient itself. He saw structures like temples and shrines as outward manifestations of inner spiritual and psychological realities – an idea deeply resonant with Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious.

Eliade’s writings went on to influence a generation of architects interested in creating spaces of deep symbolic and spiritual resonance. Designers of religious and memorial architecture, such as Tadao Ando and Maya Lin, have created environments that draw on the archetypal power of sacred geometry, natural symbolism, and collective memory to evoke profound inner experiences in visitors.

Jungian ideas also shaped broader movements in human-centered and place-sensitive architecture in the late 20th century. The architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander, for instance, was inspired by Jung’s concept of archetypes to develop his influential “pattern language” approach to architecture. When we interviewed new urbanist architect Leon Krier on our podcast about the similarity between his designs and Jung’s theories applied vissually he mentioned that he was influenced by Alexander’s designs.

In books like A Pattern Language (1977) and The Timeless Way of Building (1979), Alexander argued that certain spatial configurations and design elements have a universal, archetypal quality that resonates deeply with the human psyche. Rooms with good natural light, intimate enclosures, and views of nature, for instance, seem to tap into fundamental human needs that transcend individual cultures.

While Alexander did not directly cite Jung, his emphasis on the “timeless way” and the psychological power of certain design patterns clearly echoes Jungian notions of the collective unconscious and archetypal symbolism. Alexander’s ideas went on to influence a wide range of architects and urban planners interested in creating more humane and livable environments.

Another key figure in weaving Jungian ideas into architectural discourse was Gaston Bachelard, the French philosopher whose poetic meditations on space and memory have become touchstones for architects and designers. In books like The Poetics of Space (1958), Bachelard explored the psychological and symbolic resonances of intimate spaces like houses, attics, and drawers.

For Bachelard, the house was not just a physical shelter, but a psychic space shaped by memory, imagination, and reverie. He argued that the symbolic images and experiences associated with different domestic spaces – the warmth of the hearth, the mystery of the attic, the security of the nest – were not just personal quirks, but manifestations of deeper archetypal structures in the human psyche.

While Bachelard drew more from phenomenology than from analytical psychology, his emphasis on the collective symbolic resonances of built spaces clearly aligned with Jungian notions of the archetypal depths of the psyche. His lyrical explorations of how architecture shapes our inner worlds inspired generations of architects and theorists to consider the psychological dimension of their work.

So while Jung’s impact on architecture was often indirect, filtered through thinkers and designers who adapted his ideas in unique ways, there is no question that his concepts of archetypes, the collective unconscious, and symbolic resonance helped shape key currents in 20th century architectural thought and practice.

From the spiritual-scientific explorations of Rudolf Steiner to the archetypal place-making of Christopher Alexander to the poetic musings of Gaston Bachelard, Jung’s vision of a symbolically charged and psychologically resonant built environment left a lasting mark on modern conceptions of architecture’s role in the inner life of individuals and cultures. His ideas remind us that the spaces we inhabit are not just functional containers, but mirrors and catalysts of the deep structures of the human psyche.

Jung, Art, and the Visionary Imagination

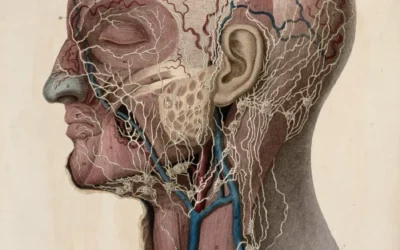

Jung’s ideas entered the art world both directly through his own artistic endeavors, and indirectly through his general theories of creativity and the cultural unconscious. Jung was a prodigious producer of fantastical, mythopoetic artworks – his famous Red Book resembles something between a medieval illuminated manuscript and a psychedelic graphic novel. For Jung, such artistic expression was a key method of engaging with the unconscious, a way to give form to the numinous archetypal images within.

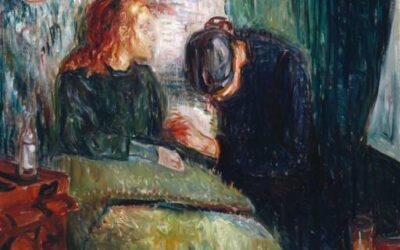

Jung felt modern humans were trapped in a spiritual crisis, cut off from the deeper wellsprings of the creative unconscious by an overly rational, materialist worldview. He saw the artist as a potential savior here, a “primordial man” who could delve into the collective unconscious and return with revivifying symbols for the culture. This deeply resonated with many modern artists who felt called to be shamanic seers rather than just aesthetic producers.

The Surrealist movement, led by figures like Andre Breton and Salvador Dali, shared Jung’s fascination with dreams, myths, and the bizarre landscapes of the unconscious. Breton was inspired by Jung’s book Psychological Types and his notion of introversion, which validated the surrealist penchant for inner visions.

Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko also heeded the surrealist credo of spontaneous creation from unconscious depths – a clear parallel to Jung’s technique of active imagination. The prominent Jungian analyst Aniela Jaffé even described Pollock’s drip paintings as modern mandalas, those “cryptograms of the self” spontaneously arising from the depths.

Jung’s influence also spread into visionary and outsider art, those raw expressions of inner worlds untethered from cultural conventions. The most striking example is Art Brut – the “raw art” of psychiatric patients collected by Jean Dubuffet. Dubuffet shared Jung’s view of the mentally ill as potential oracles of the unconscious. Dubuffet even collaborated with the Jungian matriarch Olga Froebe-Kapteyn, founder of the Eranos conferences, to study the universal nature of archetypal symbols in psychotic art.

Jung, Eco-psychology and the New Age

Starting in the 1960s counterculture, Jung’s ideas began to meld with environmental and New Age thought streams – a perhaps surprising development given his spirituality was more inner-focused than world-embracing. But many in the back-to-the-land and deep ecology movements saw Jung’s notion of a collective unconscious as a key to re-connecting humans with the lost “psyche of nature.”

The influential eco-psychologist Theodore Roszak, for example, proposed in his book The Voice of the Earth that the deepest layers of the Jungian unconscious were linked to the living intelligence of the planet itself – the anima mundi. James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis, which framed the earth as an intelligent super-organism, also shared an affinity with Jung’s view of a psychically charged cosmos.

The burgeoning New Age, with its emphasis on alternative spirituality, holistic healing and expanded consciousness, also helped popularize Jung’s thought, albeit sometimes in a superficial form. Jung’s mysterious, meaning-drenched unconscious was a natural fit for a movement fascinated by astrology, channeled revelations, and altered states – so much so that Jung’s heirs have struggled to untangle his legacy from mere mystical obscurantism.

But it’s undeniable that Jung helped set the stage for this occult revival, by re-legitimizing topics like alchemy, parapsychology, and synchronicity as worthy of study – not just archaic superstitions to be dismissed. The famous psychedelic evangelist Terence McKenna spoke of Jung as a “psychonaut” who helped map the visionary realms that substances like LSD and psilocybin opened up. Even the CIA’s notorious “psychic spying” (remote viewing) experiments in the 1970s-90s owe a strange debt to Jung’s perceived role in re-opening the doors of perception.

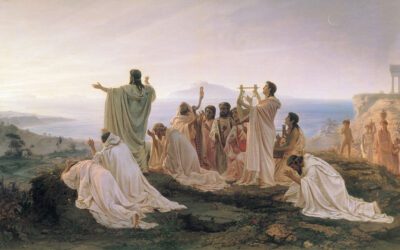

Jung and Joseph Campbell both exerted a powerful influence over the mythical dimensions of the 1960s counterculture. Together their theories gave a generation of psychonauts and spiritual seekers a profound framework for their explorations: The trip was a sacred quest, a journey into the underworld of the psyche, which if navigated properly could lead to deep personal growth and a re-connection to primal spiritual wellsprings. Without Jung, the Age of Aquarius may have been a bit less starry-eyed.

The Mythical Roots of Anthropology

Jung’s thought also bled into anthropology and the study of religion, via his correspondences with scholars like Mircea Eliade, Karl Kerenyi, and Joseph Campbell. By framing myths as expressing psychological universals rather than just outdated historical beliefs, these thinkers helped transform the budding discipline.

Eliade, the influential historian of religion, took myth to be a carrier of “sacred time” – a means for cultures to reconnect with archetypal creation stories. He saw the shaman’s trance journey as a creative return to the in illo tempore, the primal dreamtime of origins. This perspective, with its clear parallels to Jung’s view of the healthy psyche-nature relationship, helped shape the emerging archetypal school in anthropology.

Similarly, anthropologists like Claude Levi-Strauss and Victor Turner applied variations of Jung’s theory of archetypes to the study of mythology, kinship systems, and rituals. Levi-Strauss proposed that the structure of myths worldwide followed an “eternal return” pattern akin to musical themes – a notion highly resonant with the Jungian collective unconscious. Turner saw rites of passage as symbolic journeys of death-rebirth, reflecting archetypal processes of psychic transformation.

Pushing further, the archetypal psychologist James Hillman (a former director of the Jung Institute) re-visioned anthropology as the study of “archai” – the root metaphors and myths that undergird all cultures. For Hillman, psychology and anthropology are inseparable because both are ultimately expressions of the creative human imagination as it impregnates the world with meaning.

Jung’s approach thus helped steer elements of anthropology and religious studies towards a more symbolic, comparative, and experiential perspective. Rites and myths became not just relics to be decoded, but living symbols of an eternal human story.

Jung’s Personality Theory and the MBTI

Perhaps the most popularly recognized elements of Jung’s theory today are his personality concepts of introversion-extraversion and the cognitive functions of thinking-feeling and sensing-intuition. Jung proposed these as universal typological categories in his book Psychological Types (1921). He speculated that each person had an inborn preference for either intro- or extraversion and for one of the four functions, with the remaining functions being less conscious.

Jung saw psychological types not as restrictive labels but as a tool for understanding the diversity of human psychology. Still, his system was far from scientifically validated. The concepts were more derived from armchair theorizing and historical research than from controlled experiments.

Nevertheless, Jung’s personality theory was later elaborated into the Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator (MBTI), a hugely popular psychometric instrument developed by the mother-daughter team of Katherine Briggs and Isabel Myers in the 1940s-50s. The MBTI expanded Jung’s typology into 16 personality types like INTJ and ENFP, each with an ideal career path. By the 1980s, the MBTI had become a staple of corporate HR departments and popular self-help books like Please Understand Me.

Personality researchers, however, have mostly rejected the MBTI as overly simplified and unscientific. The forced-choice questions produce inconsistent results, and studies show MBTI scores do not consistently predict job performance or satisfaction. Most prefer more empirically-grounded, multidimensional models like the Big Five.

Still, the MBTI and its offshoots (like the Keirsey Temperament Sorter) remain stubbornly popular, in part because of their simplicity and optimistic focus on self-understanding rather than diagnostic pigeonholing. Models like the MBTI also spawned a whole genre of “type-watching,” with books applying personality categories to everything from romance to spirituality to dog breeds. Personality has become folk-psychology’s favorite lens.

So while Jung’s personality theory has been mostly superseded in academic psychology, it undeniably shaped popular culture’s understanding of selfhood and identity. Notions like introversion and the “Thinking vs Feeling” divide are now ubiquitous. For better or worse, when we try to understand ourselves or a potential partner today, there’s often a bit of Jung in the background.

The Mythical Roots of Ritual

One of the most direct and impactful lines of Jungian influence on modern storytelling ran through the work of Joseph Campbell, the famed comparative mythologist. Campbell’s seminal 1949 book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces, laid out the concept of the “monomyth” – the idea that myths and heroic narratives from around the world all shared a common deep structure, which Campbell summarized as the “Hero’s Journey.”

For Campbell, this recurring pattern – in which a hero ventures from the everyday world into a realm of supernatural wonder, faces trials and temptations, gains a decisive victory, and returns transformed to bestow boons on his fellow man – was far more than just a literary curiosity. Drawing heavily on Jung’s theories of archetypes and the collective unconscious, Campbell saw the monomyth as a symbolic expression of universal psychological processes – a roadmap for the individuation of the self.

In Campbell’s Jungian reading, the hero’s outward journey mirrors an inward one – a psychic odyssey into the depths of the unconscious, where the ego must confront and integrate the archetypal forces that reside there. The various challenges and figures the hero encounters – threshold guardians, helpful mentors, shape-shifting tricksters, anima/animus figures – all represent aspects of the psyche that must be recognized, engaged with, and ultimately transcended on the path to wholeness.

Campbell’s monomyth model had a seismic impact on modern storytelling, particularly in the realm of film and television. In the 1970s and 80s, Hollywood underwent a narrative revolution, as a new generation of directors – the so-called “movie brats” – began consciously crafting their films around Campbell’s archetypal structure.

George Lucas famously used The Hero With a Thousand Faces as a direct template for Star Wars (1977), with Luke Skywalker’s journey hitting all the key beats of the monomyth. Other blockbusters of the era, from The Lion King (1994) to The Matrix (1999), similarly leaned heavily on the Campbellian formula, to the point where the Hero’s Journey became a kind of narrative lingua franca in mainstream entertainment.

But Campbell’s influence on modern storytelling went deeper than just plot structure. In framing the Hero’s Journey as a symbolic enactment of psychological and even metaphysical processes, Campbell helped reintroduce a mythic dimension to popular culture at a time when traditional religious narratives were losing their hold on the mass imagination.

The notion that every story is ultimately a cipher for timeless spiritual truths, a reflection of an archetypal quest for meaning and transcendence, became a key subtext of much modern storytelling. Films like Star Wars or The Matrix were not just entertaining adventures, but modern myths – allegories of the soul’s journey towards enlightenment, encoded with esoteric wisdom and metaphysical significance.

This mythic sensibility – the sense that there is always a deeper symbolic or philosophical layer to the story being told – has become a defining feature of much contemporary pop culture. From the elaborate world-building of the Marvel Cinematic Universe to the mind-bending mysteries of shows like Lost or Westworld, modern audiences have come to expect their entertainment to be laced with hidden meanings, Easter eggs, and metaphysical head-scratchers.

In a sense, this is the narrative equivalent of what media theorists have dubbed the “metaverse” – the idea of a shared virtual space where the boundaries between different stories, properties, and even realities start to blur. Just as the metaverse promises a kind of trans-medium storytelling, where characters and storylines can flow seamlessly across different platforms and fictional universes, the Campbellian monomyth provides a kind of archetypal substrate that underlies and connects seemingly disparate narratives.

Of course, the universalism of Campbell’s model has also come under criticism from some quarters. By emphasizing the common patterns that unite different mythological traditions, Campbell arguably downplayed the specific cultural, historical, and political contexts that shaped these stories. His work has been accused of promoting a kind of ahistorical, decontextualized view of myth that can shade into a bland, New Age universalism.

There have also been challenges to the gendered assumptions built into the Hero’s Journey template, with its emphasis on male protagonists undertaking active, outward-facing quests. Feminist critics have argued for alternative mythic patterns that better reflect women’s experiences and perspectives, such as the “Heroine’s Journey” model proposed by Maureen Murdock.

Despite these critiques, however, there is no denying the enduring influence of Campbell’s mythic vision on modern storytelling. The idea that every tale is a reflection of the same few archetypal narratives, that each hero is an avatar of the same fundamental psycho-spiritual quest, has become a kind of default frame for much contemporary fiction.

In this sense, Campbell’s work represents perhaps the most successful popular translation of Jung’s ideas into the realm of culture and creativity. By recasting the archetypes of the collective unconscious as the building blocks of all storytelling, Campbell helped ensure that Jung’s key insights would continue to shape our imaginative lives well into the 21st century.

Nowadays, the “meta” dimension of storytelling that Campbell helped pioneer has become an almost inescapable part of our narrative landscape. From the hyper-referential, Easter egg-laden movies of the MCU to the labyrinthine, fan theory-spawning storylines of prestige TV, we live in an age where every story seems to contain a hidden story, where surface meanings always gesture towards secret depths.

In a sense, this is the narrative correlate of the Jungian worldview – the notion that the visible world is always haunted by unseen archetypes, that the conscious mind is but the tip of a vast psychic iceberg. Just as Jung saw the self as a kind of archaeological dig, a process of uncovering ever-deeper layers of symbolic meaning, modern storytelling invites us to be our own mythological detectives, piecing together the hidden significances and correspondences that lurk beneath the surface of the tale.

Of course, as with any successful formula, the Campbell-Jung mythic model has also at times devolved into a kind of rote, paint-by-numbers approach to storytelling. The “hero goes on a quest” template can easily become a lazy crutch, a way to imbue a mediocre story with an unearned sense of archetype and import.

And there is always the risk that in reducing all narratives to a single archetypal monomyth, we flatten the rich diversity of human storytelling traditions, the myriad ways that different cultures have made sense of their world through myth, folklore, and legend. The universal must not come at the expense of the particular.

But at its best, the Campbell-Jung synthesis provides a powerful lens for understanding the deep psychological and even spiritual yearnings that animate our fictions. It reminds us that stories are not just diverting entertainments, but mirrors of our deepest selves, encoded with the secret keys to personal transformation and growth.

In a world where the old mythic frameworks that once gave meaning to human life have largely fallen away, the Campbellian vision of storytelling as a kind of ersatz religion, a gateway to the eternal and the numinous, takes on a renewed urgency. We may no longer look to the heavens for our myths, but we still hunger for stories that can reconnect us to the archetypal dimensions of existence.

Whether in the form of a sci-fi blockbuster or a prestige TV drama, a sprawling metaverse or an intimate character study, the stories we tell ourselves continue to serve this vital psycho-spiritual function. They are the means by which we navigate the depths of the psyche, confront our shadows, and quest after the grails of wholeness and self-realization.

This, perhaps, is Joseph Campbell’s greatest legacy, and the most enduring testament to the cultural impact of Jungian ideas: the notion that every story, no matter how humble or fantastical, is ultimately a hero’s journey – a symbolic atlas of the soul’s hidden geographies, waiting to be explored.

Romantic Love and the Syzygy

One of Jung’s most fascinating (and controversial) archetypal ideas was the syzygy: the divine union of contrasexual opposites, personified in the unconscious by the anima/animus pair. Jung believed that every man harbored an unconscious feminine side (the anima, the archetype of life/soul), while every woman possessed a masculine inner figure (the animus, the archetype of meaning/spirit).

The task of individuation, for Jung, involved not repressing these contrasexual archetypes but coming into conscious relationship with them, integrating their creative energies. Only then could one be truly psychologically whole, ready for mature love with a real outer partner.

This “divine couple” motif, with its obvious resonance to romantic love, made a major impact on popular culture. Books like Robert A. Johnson‘s He, She, and We: Understanding the Psychology of Romantic Love (1983) became bestsellers by offering a Jungian take on relationships. Johnson argued that romance often fails because we project our anima/animus onto our partners, expecting them to complete us in an impossible way.

Jungian analyst Jean Shinoda Bolen’s hugely popular Goddesses in Everywoman (1984) and Gods in Everyman (1989) rooted this romantic dynamic in Greek mythology. Bolen proposed seven feminine archetypes – Artemis, Athena, Hestia, Hera, Demeter, Persephone, and Aphrodite – that shape women’s identities and relationships. Each goddess represents a different mode of being and loving, from Artemis’ independent autonomy to Hera’s jealous devotion.

Other writers applied the syzygy concept even more broadly. The eco-philosopher Riane Eisler saw in the “sacred marriage” of masculine and feminine a blueprint for the partnership society, an ancient egalitarian alternative to patriarchal dominator culture. For Eisler, the clash between partnership and dominator values is the key polarity running through all of human history.

On a more esoteric level, Jung’s syzygy concept shaped several schools of new age and modern Gnostic thought. The Wiccan notion of the cosmic Goddess and God united in sacred marriage contains a strong dose of alchemical syzygy symbolism – the conjunction of opposites as the mystic key to spiritual rebirth.

Despite these limitations, the syzygy remains a potent (and often misused) part of the modern romantic imagination. It offers a tantalizingly simple way to project cosmic meaning onto the dramas of love. Popular books like The Path to Love (1993) by Deepak Chopra continue to invoke anima/animus integration as the secret to soulmate bliss and the “mystical union” of tantric sex.

So while Jung’s model of love may not hold up to our contemporary gender politics, it clearly touched a nerve in the popular psyche. In a hyper-individualistic culture, the syzygy holds out the promise of a relationship that can make us spiritually whole – the jigsaw puzzle of self completed by the beloved other. Though perhaps impossible, this romantic fantasy still enchants and beguiles.

The Archetype of the Mandala

No image is more emblematic of Jung’s thought than the mandala: the circular, geometric pattern representing wholeness and cosmic order. Derived from Hindu and Buddhist iconography, where it often depicts the sacred domains of deities, the mandala became for Jung an expression of the transpersonal Self’s radiant totality.

Jung first encountered mandalas in the visionary experiences he recorded in The Red Book, his famously esoteric record of a creative “confrontation with the unconscious.” He felt compelled to paint mandala-like images during this period, which became a key technique in his discovery of active imagination – the method of engaging the psyche through expressive dialogue rather than just passive analysis.

For Jung, the urge to create or contemplate mandalas often emerged in states of psychic turbulence – a kind of spontaneous self-healing impulse by the deep psyche. The mandala’s quaternary structure (a circle with a cross inside) reflected the fourfold wholeness of the Self, transcending the dualistic divisions of ego-consciousness.

Jung collected and compared mandala images from various cultural traditions, including Navajo sand paintings and medieval Christian depictions of the quaternity (e.g. the four evangelists). He saw these parallels as evidence of the mandala as a universal expression of the collective unconscious’s central archetype of order.

Jung’s writings on the mandala influenced a host of modern scholars and artists. The historian of religion Mircea Eliade analyzed mandalas as an example of the “axis mundi” (world axis) archetype, demarcating a sacred center where divine forces interpenetrate the earthly realm. Eliade saw mandalas as one way traditional societies oriented themselves in consecrated space and time.

In the budding new age movement, Jung’s mandala concept mixed with Eastern spiritual ideas to shape practices like yantra meditation and guided visualization. The transpersonal psychologist Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass) famously led “mandala sessions” at Harvard in the early 1960s, encouraging subjects to depict their visionary experiences while under the influence of psychedelics.

The concept also inspired reflections on the mandala-like nature of the psyche itself. The Jungian analyst and storyteller Clarissa Pinkola Estés saw the Self as a “mandorla” (almond-shape formed by two overlapping circles), symbolizing the fertile union of opposites at the core of creative individuation. New age thinkers like Jose Arguelles and Ken Wilber went even further, envisioning an evolutionary “mandala of consciousness” leading to global integration.

Perhaps most consequentially, the mandala became a staple of meditative coloring books and spiritual self-help practices. Coloring mandalas is now a common technique for cultivating mindfulness and even processing trauma. No longer just an esoteric rumination aid, the mandala has become the mass-market face of therapeutic art and visualization.

As with much of Jung’s thought, the mandala’s popularization has sometimes come at the cost of depth and nuance. Modern coloring books often emphasize the mandala’s calming symmetry while downplaying its shadow side – the chaos and fragmentation that are as much the psyche’s truth as wholeness and integration.

Still, at its best, the mandala remains a potent “yantra” (instrument) of contemplative practice – an evocative reminder of the psyche’s mysterious, self-organizing energies. By visualizing a sacred center within the flux of experience, the mandala can become a container for our darkest and most luminous encounters with soul.

Synchronicity and the “New Paradigm”

One of Jung’s most fascinating (and controversial) ideas is the concept of synchronicity: meaningful coincidences that seem to defy causal explanation, hinting at an underlying unity between mind and matter. Jung developed the theory in collaboration with the quantum physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who saw in synchronicity a possible bridge between modern physics and depth psychology.

Jung defined synchronicity as “a coincidence in time of two or more causally unrelated events which have the same or similar meaning.” A classic example would be dreaming of an unusual animal, then unexpectedly receiving that animal as a gift the next day. For Jung, such “acausal connecting principles” were evidence that the psyche is not limited to the personal unconscious but partakes of a deeper layer of objective reality.

Jung’s synchronicity theory became wildly influential in the burgeoning “new paradigm” movement of the 1960s and 70s. Thinkers like Fritjof Capra (The Tao of Physics) and Gary Zukav (The Dancing Wu Li Masters) saw quantum indeterminacy and nonlocality as evidence of a holistic, participatory universe in line with Eastern mysticism. Synchronicity was often invoked as a sign of the cosmic interconnectedness of all things.

The new age and human potential movements also embraced synchronicity as a key to spiritual awakening and manifestation. Figures like Deepak Chopra and James Redfield (The Celestine Prophecy) made synchronicity a staple of mind-body-spirit literature, a “secret” behind the art of flow and serendipitous living. The anthropologist Richard Tarnas even proposed a “participatory epistemology” centered on synchronicity as a challenge to the alienated subject-object divide of modern science.

More recent proponents have linked synchronicity to fields like complexity theory and morphogenetic fields. The biologist Rupert Sheldrake, for example, has proposed that synchronicities may be related to his theory of “morphic resonance,” the idea that self-organizing systems are shaped by memory-like patterns in the vacuum of space. For Sheldrake, synchronicity is a sign that the universe is far more integral and purposive than the materialist paradigm allows.

Of course, Jung’s idea has also been roundly critiqued by skeptics as a mystification of sheer coincidence and the human tendency to seek patterns in random events. The psychologists Nicholas Humphrey and Daniel Dennett have argued that synchronicity is simply an artifact of the mind’s relentless search for meaning in an inherently chaotic and meaningless universe.

Other scholars have critiqued the cultural appropriations and orientalism involved in the new age adoption of synchronicity. The idea is often used to give a scientific veneer to magical thinking, or to bypass the hard work of political engagement in favor of a facile “flow” with the universe. Too often, synchronicity becomes a cheap tool for dodging the specter of randomness and uncertainty.

Despite these valid concerns, Jung’s concept of synchronicity remains a powerful one in the contemporary spiritual imagination. In a world that often feels fragmented and alienating, synchronicity holds out the tantalizing possibility of a deeper, enchanted order humming beneath the surface of things. The feeling of the universe as “winking” at us in moments of numinous coincidence seems to be a genuine element of human experience, even if we should be cautious about weaving metaphysical theories from such encounters.

At its best, synchronicity can be a spur to a humbler, more participatory engagement with the mystery of being. By startling us out of our “mind-forged manacles” of total causal explanation, synchronicity reminds us that psyche and matter may not be so irrevocably cleaved as modernity assumes. Mind and world are perhaps more intimate than we know — two faces of a unitary reality that occasionally peeks out from behind the veil of happenstance.

The Cultural Legacy of Jungian Ideas

In tracing the manifold influence of Carl Jung on modern thought, we’ve seen how his ideas rippled out into a dizzying array of fields — from art and literature to anthropology, religion, ecology, and even physics. Jung’s thought seems to have functioned as a kind of alchemical vessel, a catechistic glass in which the dreams of the age could find unique expression and combination.

This cultural legacy is all the more remarkable given that Jung himself was often ambivalent about his role as a guru-figure. Unlike Freud, he didn’t try to build up a grand institutional edifice to carry on his work. He distrusted doctrinaire “schools” of thought, and instead emphasized the irreducible singularity of each person’s confrontation with the unconscious.

One could say that Jung’s influence spread more like spores on the wind than a lineage transmitted through direct academic and therapeutic descendants. His ideas cross-pollinated with parallel trends in the Zeitgeist, often in wild and uncontrolled ways that far exceeded Jung’s original intentions. Figures as disparate as Philip K. Dick, Terence McKenna, and New Age religious leaders could claim him as forefather.

Part of Jung’s appeal was surely his emphasis on firsthand experience of the numinous — his insistence that the psyche is real in a way that transcends the “dead matter” models of modern science. For a generation of seekers disillusioned with the empty consumerism of post-war society, Jung’s ideas offered a way back to the re-enchantment of the world, the rediscovery of a sacred dimension lurking beneath the surface of the mundane.

Yet this “mushroom syndrome” in Jung’s influence also had its shadow side. In his later years, Jung often worried that his work was being misused as a kind of spiritual panacea, a “substitute for the lost gods.” He insisted that individuation meant engaging with the concrete realities of embodiment, not escaping into a mystical beyond.

Jung’s legacy has also been critiqued for its political ambiguities. While he clearly rejected the racist doctrines of Nazism, Jung was not entirely immune to the fascist mystique of the era. His early writings on “Aryan” and “Jewish” psychology, while couched in the language of collective unconscious, have an uncomfortable resonance with the Völkisch theories of the time.

Feminists have also taken Jung to task for his conception of the anima/animus, which relies on rather essentialist notions of masculine and feminine principles. While Jung saw these archetypes as transcending biological sex, his binary model doesn’t neatly map onto the gender-fluid landscape of the 21st century. The syzygy, in particular, has often been invoked to give a cosmic gloss to heteronormative models of romantic fulfillment.

Despite these limitations, Jung’s thought remains a powerful ferment in the contemporary imagination. His ideas continue to inspire artists, writers, and thinkers grappling with the perennial crises of meaning in a secular age. In a world still largely dominated by the ghost of Cartesian dualism, Jung’s vision of psyche as objective reality provides a potent counterpoint, an opening to the re-sacralization of nature and cosmos.

Perhaps the most enduring insight of Jung’s legacy is the recognition that the human psyche is ultimately irreducible to neat rational formulae. We are not transparent to ourselves, and never entirely in control of the forces that move through us. The call to individuation is not a hero’s journey of the ego, but a far more mysterious and paradoxical navigation of the autonomous psyche in both its light and shadow aspects.

As our planetary civilization faces a mounting crisis of meaning and sustainability, Jung’s call to reconnect with the deep roots of the collective unconscious feels more relevant than ever. We need myths and symbols that can bind us together in a shared vision of human and cosmic flourishing — not as an escape from political realities, but as a crucible for the inner transformation that must precede any authentic social change.

Other areas of thought that Jung Influenced

Psychology and Therapy

Analytical Psychology – Founded by Jung himself, focusing on individuation, archetypes, and the collective unconscious.

Archetypal Psychology – Developed by James Hillman, focusing on archetypes and imagination as central to the psyche.

Humanistic Psychology – Influenced by Jung’s optimism about human potential and the process of individuation.

Transpersonal Psychology – Focused on spiritual and transcendent aspects of the psyche, deeply inspired by Jung’s work on the collective unconscious and mysticism.

Depth Psychology – A broad school emphasizing unconscious processes, stemming from Freud and Jung’s foundational work.

Narrative Therapy – Inspired by the archetypal and symbolic importance of personal stories and myths in shaping identity.

Positive Psychology – Echoes Jung’s ideas on self-actualization and the exploration of meaning.

Philosophy

Existentialism – Shares thematic parallels with Jung’s focus on meaning, authenticity, and the confrontation with the unconscious.

Phenomenology – Influenced by Jung’s work on subjective experience and archetypal patterns of perception.

Integral Theory – Developed by Ken Wilber, merging psychology, spirituality, and cultural studies, with Jung’s work as a major component.

Hermeneutics – Jung’s symbolic interpretation of myths and dreams contributed to philosophical approaches to meaning and interpretation.

Anthropology and Mythology

Symbolic Anthropology – Focused on cultural symbols and rituals, paralleling Jung’s study of archetypes and their cross-cultural expressions.

Comparative Mythology – Influenced by Jung’s archetypes and his collaboration with figures like Joseph Campbell.

Cultural Relativism – Aligns with Jung’s recognition of the diverse yet universal expressions of archetypes in different cultures.

Religion and Spirituality

New Age Movement – Strongly influenced by Jung’s focus on mysticism, alchemy, and Eastern spirituality.

Depth Theology – Figures like Paul Tillich and Rudolf Otto integrated Jungian ideas into theological discussions about the sacred and the psyche.

Esotericism and Alchemy – Jung’s work on alchemy revived interest in esoteric traditions, influencing contemporary spirituality.

Interfaith Dialogue – Jung’s cross-cultural studies of religious symbols contributed to greater understanding between traditions.

Literature and Storytelling

Mythopoetic Literature – Authors like J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were influenced by Jungian ideas about myth and archetypes.

Narrative Psychology – Built on Jung’s insights into archetypes and their role in personal and collective storytelling.

Modernist and Postmodernist Literature – Writers like James Joyce and Hermann Hesse incorporated Jungian themes of individuation and the unconscious.

Screenwriting and the Hero’s Journey – Joseph Campbell’s adaptation of Jung’s archetypes shaped storytelling in cinema, such as in Star Wars.

Art and Aesthetics

Surrealism – The exploration of the unconscious in Surrealist art resonates with Jung’s ideas of archetypes and dreams.

Abstract Symbolism – Artists like Kandinsky and Paul Klee explored Jungian ideas of universal symbols and the spiritual in art.

Visionary Art – Artists like Alex Grey indirectly drew from Jung’s archetypal and mystical themes.

Cultural Movements

Human Potential Movement – Focused on self-actualization and spiritual growth, heavily inspired by Jung’s work on individuation.

Mythopoetic Men’s Movement – Led by figures like Robert Bly, drawing on Jung’s archetypes to explore masculinity and rites of passage.

Romantic Revivals – Indirectly inspired by Jung’s emphasis on the symbolic and emotional depth of human experience.

Politics and Sociology

Cultural Psychology – Jung’s ideas on collective unconsciousness influenced how sociologists and anthropologists study cultural identity.

Critical Theory – Indirectly influenced by Jung’s critique of modernity and his exploration of collective psychological patterns.

Communitarianism – Resonates with Jung’s emphasis on community and shared symbolic meaning as a counterbalance to individualism.

Postmodernism – Jung’s focus on multiple truths and archetypal diversity influenced cultural relativism and postmodern thought.

Education

Experiential Education – Indirectly inspired by Jung’s emphasis on inner exploration and personal growth.

Myth-Based Education – Programs incorporating storytelling and archetypes as tools for teaching.

Science and Medicine

Psychosomatic Medicine – Jung’s emphasis on the mind-body connection influenced the development of holistic approaches to health.

Psychedelic Research – Studies of altered states of consciousness have drawn on Jungian frameworks for understanding inner experiences.

Architecture and Design

Symbolic and Organic Architecture – Movements like Anthroposophical architecture and sacred geometry reflect Jungian ideas of archetypes and harmony.

Biophilic Design – Reflects Jung’s ideas about nature’s psychological resonance and its symbolic significance.

Critical Regionalism – Emphasizes the psychological and cultural meaning of place, paralleling Jungian thought.

Business and Organizational Studies

Organizational Archetypes – Jung’s archetypes have been applied to leadership and corporate culture.

Branding and Marketing – Psychological branding strategies use Jungian archetypes to connect with audiences.

Other Cultural Areas

Feminist Movements – Jung’s ideas on the anima and animus contributed to discussions about gender and psychology.

Ecopsychology – The integration of Jung’s ideas on nature and the psyche into ecological studies and environmental movements.

Meditative and Mindfulness Practices – Jung’s interest in Eastern philosophy influenced the Western adoption of mindfulness and meditation.

Bibliography:

- Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (Collected Works of C.G. Jung Vol.9 Part 1). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological Types (Collected Works of C.G. Jung Vol.6). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Shamdasani, S. (2003). Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bair, D. (2003). Jung: A Biography. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

- Stevens, A. (1994). Jung: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Rowland, S. (2005). Jung as a Writer. London, UK: Routledge.

- Bishop, P. (2014). Carl Jung (Critical Lives). London, UK: Reaktion Books.

- Cambray, J. (2014). Synchronicity: Nature and Psyche in an Interconnected Universe. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

- Haule, J. R. (2011). Jung in the 21st Century Volume One: Evolution and Archetype. London, UK: Routledge.

- Main, R. (2004). The Rupture of Time: Synchronicity and Jung’s Critique of Modern Western Culture. Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

- Tacey, D. (2001). Jung and the New Age. Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

- Hillman, J. (1992). Re-Visioning Psychology. New York, NY: HarperPerennial.

- Tarnas, R. (2006). Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. New York, NY: Plume.

- Rowland, S. (2002). Jung: A Feminist Revision. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. London, UK: Routledge.

0 Comments