“My point, once again, is not that those ancient people told literal stories and we are now smart enough to take them symbolically, but that they told them symbolically and we are now dumb enough to take them literally.”

― John Dominic Crossan, Who Is Jesus? Answers to Your Questions About the Historical Jesus

Main Ideas and Key Points:

1. John Dominic Crossan argues that ancient people told religious stories symbolically, while modern people often interpret them literally.

2. The development of religion has been influenced by technological advancements, cultural exchanges, and changing social and intellectual landscapes throughout history.

3. Paganism is deeply rooted in the human experience of the natural world and the collective unconscious, and its true essence and complexity are often misunderstood by modern society.

4. In the pagan worldview, gods were seen as manifestations of the divine within the natural world, embodying the forces and patterns that govern the universe.

5. The modernist movement in art, particularly the works of Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and James Joyce, was influenced by the concept of the hieroglyphic method and the logic of metaphor, which are closely tied to the symbolic thinking in the pagan worldview.

6. The Greeks and other ancient cultures did not believe in mythical beings as literal entities, but rather as complex sets of associations and representations of particular powers or aspects of nature.

7. Paganism places a strong emphasis on community, relationship, and the fundamental interdependence of all beings, recognizing the importance of cultivating harmonious relationships with others and the natural world.

8. Unbridled egoism in science and technology can lead to the accumulation of wealth and power, the pursuit of immortality through material means, and the creation of artificial intelligence that may threaten the natural world and human consciousness.

9. Language in pagan traditions was seen as a sacred and transformative force, imbued with the power to shape reality and connect humans with the divine, in contrast to the modern view of language as a static medium for transmitting information.

10. The emergence of language and writing played a crucial role in the development of religious beliefs, with the creation of writing enabling the conception of cosmic beings and powers governing the mysteries of existence.

11. Death plays a pivotal role in the creation of meaning and the evolution of language, as the language we speak is shaped by the collective experiences and wisdom of all those who have come before us, connecting the living with the dead.

12. Clues to early religion in prehistory can be found in the use of symbolism, Paleolithic burials and the afterlife, the emergence of shamanism, the Neolithic Revolution and the rise of organized religion, and the invention of writing and the codification of religious beliefs.

13. The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture in Siberia provides early evidence of symbolic thought, ritual behavior, and mythology that may have influenced later religious traditions through migration and cultural diffusion.

14. Sacred landscapes, such as mountains, caves, and springs, were imbued with spiritual significance in prehistoric times and shaped the development of religious practices and beliefs.

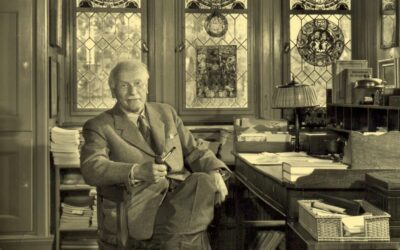

15. The theories of James George Frazer, Mircea Eliade, Erich Neumann, and Carl Jung offer valuable insights into the nature and development of paganism, but also have limitations and have been subject to criticism.

16. Modern philosophies and movements such as post-modernism, neo-paganism, animism, deep ecology, and ecofeminism share similarities with pagan thought and practices, emphasizing the sacredness of nature, the importance of subjective experience, and the rejection of dualistic thinking.

Timeline of the Development of Religion and Technological Progress

Pre-literate Societies (Before 3500 BCE):

Religions were primarily oral traditions, passed down through myths, rituals, and storytelling.

Animism, shamanism, and ancestor worship were common religious practices.

Artifacts, such as cave paintings and burial practices, provide insight into early religious beliefs.

Invention of Writing (Around 3500 BCE):

The development of writing systems, such as cuneiform in Mesopotamia and hieroglyphs in ancient Egypt, allowed for the recording of religious texts and beliefs.

Religious myths, prayers, and rituals were preserved in written form, leading to the establishment of more organized religious systems.

The invention of writing facilitated the spread and preservation of religious teachings across generations.

Ancient Civilizations (3000 BCE – 500 CE):

Major religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, and the precursors to Christianity and Islam, emerged and developed sacred texts.

The production of religious manuscripts, scrolls, and codices enabled the dissemination of religious teachings across wider geographical areas.

Religious architecture, such as temples, synagogues, and monasteries, became more elaborate and symbolic.

The Printing Revolution (15th Century CE):

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century enabled the mass production of religious texts, including the Bible and the Qur’an.

This increased accessibility to religious literature, fostering literacy and religious education among the general population.

The printing press facilitated the spread of religious ideas and contributed to the Protestant Reformation in Christianity.

The Age of Exploration and Colonialism (15th – 19th Centuries):

The exploration and colonization of new lands by European powers led to the spread of Christianity, Islam, and other religions to different parts of the world.

Encounters between different cultures and religions resulted in religious syncretism, the blending of religious practices and beliefs.

Missionary activities aimed to convert indigenous populations to the religions of the colonizing powers.

The Industrial Revolution and Modern Era (18th – 21st Centuries):

The rise of scientific knowledge and rationalism challenged traditional religious beliefs and authorities.

New religious movements, such as the Baha’i Faith and Sikhism, emerged, incorporating modern ideas and values.

The development of mass media, including print, radio, television, and the internet, facilitated the global dissemination of religious ideas and practices.

Religious pluralism and interfaith dialogue became more prevalent in many societies.

Wild things are truly alive only in the place where they belong. Away from that place they may bloom like exotics, but the eye will seek beyond them for their lost home.– J.A. Baker, The Peregrine

What is Paganism?

Throughout history, the development of religion has been influenced by technological advancements, cultural exchanges, and the changing social and intellectual landscapes. The invention of writing and other technologies played a crucial role in preserving, disseminating, and shaping religious beliefs and practices across various cultures and time periods.

Paganism, a term often used to describe a wide range of pre-Christian religious beliefs and practices, has long been misunderstood by modern society. Many people today view paganism as a simplistic belief system involving multiple gods, akin to a polytheistic version of monotheism or a late-stage Greek or Roman pantheon. However, this superficial understanding fails to capture the true essence and complexity of paganism, which is deeply rooted in the human experience of the natural world and the collective unconscious.

Another way of thinking about early mankind’s polytheism was not that there were many gods but rather that there were aspects of god everywhere. Pagans recognized the elements of the natural world that humans interacted with and depended on as pillars of creation they conversed with symbolically through religious action. The sea , the sky, the animals, the night, the sun; these were all personified elements of nature that were conversed with. After the invention and development of language and writing humans were able to ascribe more specific attributers and to personalities to these elements of nature and they became more separate entities or gods. These early gods of the natural world overlapped and were interrelated but became more separate entities as technology progressed.

Previously all this divinity was contained in the natural world through pre-Christian paganism. As technology progressed divinity was cordoned off in to separate spaces and separated from the larger world. Nature was no longer seen as the realm of the divine. Instead it became a simply a resource that man kind owned and controlled. More and more of the natural worked became seen as the domain of man not the domain of the divine.

Cordoning divinity off out of the natural world led to the slow but steady rise of monotheistic faiths that saw the world as material and secular and contained the divine to specific spaces, rituals, dates, and authority hierarchies. .

The Nature of Gods in Paganism

In the pagan worldview, gods were not seen as remote, otherworldly entities, but as manifestations of the divine within the natural world itself. They were not literal beings with human-like personalities and attributes, but rather embodiments of the forces and patterns that govern the universe. This understanding of the divine as immanent in the world is key to grasping the true nature of paganism and its connection to the cycles of life, death, and regeneration that permeate all of existence.

The gods of paganism were a way for ancient peoples to name and talk about the cognitive patterning they observed within the world, the circuits and powers that take inputs, transform them, and produce semi-predictable outputs. This concept of God as an immanent power working in the world stands in stark contrast to the view of God in monotheistic Abrahamic religions, where the divine is seen as a transcendent being who rewards and punishes human behavior.

The Hieroglyphic Method and the Logic of Metaphor The modernist movement in art, particularly the works of Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and James Joyce, was deeply influenced by the idea that there is no such thing as abstraction, only a constellation of particulars that achieves its own sort of radiation or alchemical change. This concept, known as the ideogramic or hieroglyphic method, is rooted in the way abstract concepts are recorded in ancient Chinese ideograms and other early writing systems.

The hieroglyphic method involves arranging particulars into a metaphorical field that creates something new and unexpected, rather than simply conveying a known idea. This approach to language and meaning is closely tied to the concept of the “logic of metaphor,” as described by the poet Hart Crane. The logic of metaphor suggests that a poem or work of art is not merely a paraphrase of an idea, but an exploration of the internal logic of metaphor itself, leading to the creation of something that doesn’t have a name yet.

This understanding of language and meaning is precisely the same kind of perception as the hieroglyphic metaphor used to name, describe, and talk about gods in the pagan worldview. Modernism, in resurrecting this primordial idea of God, provides a compelling presence of the old gods in the modern world, reminding us of the power and significance of symbolic thinking in the human experience.

The Misunderstanding of Pagan Mythology

The idea that the Greeks and other ancient cultures believed in a set of mythical beings who occasionally came to earth to help or harm humans is not only wrong but also insulting and damaging to our understanding of the past. A careful reading of the mythos of any god reveals a complex set of associations, familiars, imagery, and origin stories that add up to a hieroglyphic representation of a particular power or aspect of nature.

For example, the goddess Athena in Greek mythology is not merely a human-like woman who lives on a mountain, but a representation of the moment of sudden, bright insight or inspiration. Her associations with bright eyes, owls, olive trees, and the epithet “glaukopis” all contribute to this metaphorical understanding of her nature. Similarly, the gods of writing, secrecy, and death in various cultures (such as Thoth, Anubis, and Hermes) are not arbitrarily connected, but deeply linked through the idea that using written language connects one to the entire history of the dead and the process of metaphor-making that has shaped human language over thousands of years.

The Importance of Community and Relationship

Paganism places a strong emphasis on community and relationship, recognizing the fundamental interdependence of all beings and the importance of cultivating harmonious relationships with others and the natural world. Unlike later religious traditions that often prioritize individual salvation, paganism acknowledges the essential role of community in the spiritual journey.

Pagan rituals often involve the participation of the entire community and serve to strengthen social bonds and solidarity. These rituals extend the sense of interconnectedness beyond the human sphere, encompassing the relationship between humans and nature. This deep reverence for the earth and commitment to living in harmony with the natural world is a hallmark of pagan thought and practice.

The Dangers of Unbridled Egoism in Science and Technology

One of the primary ways in which this scientific egoism manifests is through the accumulation of wealth and power. In a world where the scientific method reigns supreme, material success is often seen as the ultimate measure of an individual’s worth and accomplishment. This mindset leads many to hoard far more resources than they could ever need or use in a single lifetime, driven by the unconscious belief that their vast wealth will somehow allow them to transcend the inevitability of death. However, this pursuit of immortality through material means is ultimately a futile endeavor, as no amount of wealth or power can truly overcome the fundamental impermanence of the human condition.

Another area where the unchecked ego can wreak havoc is in the development of artificial intelligence and advanced computer systems. The dream of creating a machine that can rival or even surpass human intelligence is often fueled by the desire to extend the reach of the ego beyond the limitations of the physical body. By pouring their hopes, fears, and aspirations into these technological projects, individuals may unconsciously seek to create a digital version of themselves that will persist long after their biological existence has ended. Our own neural networks unconsciously see the networks of computers as extensions and reflections of themselves. However, this attempt to achieve a form of technological immortality is fraught with peril, as it fails to recognize the fundamental interdependence of human consciousness and the natural world.

In contrast, when science and technology are pursued in harmony with a deep sense of spirituality and connection to the divine, they can become powerful tools for positive transformation. Individuals who are grounded in a higher purpose are less likely to fall prey to the egotistical impulses that drive the accumulation of wealth and power for its own sake. Instead, they may choose to use their resources and abilities to create businesses, organizations, or initiatives that serve the greater good and contribute to the well-being of future generations. This mindful approach to leadership and innovation recognizes that true legacy lies not in the perpetuation of the individual ego, but in the positive impact one has on the world and the lives of others.

Similarly, a spiritually grounded approach to parenting and education can help to foster a sense of authentic selfhood in children, rather than molding them into mere extensions of their parents’ egos. By encouraging children to explore their own unique talents, interests, and ways of being in the world, parents can nurture the development of well-rounded, emotionally resilient individuals who are capable of forging their own paths in life. This stands in stark contrast to the egotistical impulse to view children as vehicles for the continuation of one’s own legacy, which can lead to a stifling of their individuality and potential.

Ultimately, the key to avoiding the pitfalls of scientific egoism lies in cultivating a deep sense of humility and recognizing the limits of human control. While the scientific method is an incredibly powerful tool for understanding and manipulating the natural world, it is not a panacea for all of life’s challenges and mysteries. By acknowledging the existence of forces and realities that lie beyond the grasp of the rational mind, individuals can maintain a healthy balance between the pursuit of knowledge and the acceptance of the unknown. This requires a willingness to embrace the spiritual dimensions of existence and to recognize the fundamental interconnectedness of all things.

The Power of Language and the Incarnation of the Word: The Sacred Nature of Communication

In pagan traditions, language was often seen as a sacred and transformative force, imbued with the power to shape reality and connect humans with the divine. For these communities, words were not merely tools for conveying information or recording scientific knowledge; they were living entities that could bring forth the manifestation of ideas, emotions, and even physical phenomena. This understanding of language as a dynamic, creative force was deeply ingrained in the spiritual and cultural practices of pagan societies.

In contrast, modern societies that prioritize scientific empiricism and egocentrism often view language as a “dead” or static medium, primarily used for the transmission of objective data and the preservation of intellectual achievements. This perspective strips language of its inherent vitality and reduces it to a mere instrument of the rational mind. When language is seen solely as a means of recording and communicating scientific information, its potential to influence the psyche, evoke emotional responses, and facilitate spiritual growth is largely overlooked.

Pagan communities recognized that the spoken word had the ability to penetrate the depths of the human soul, influencing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in profound ways. They understood that language was not only a bridge between the realm of ideas and the material world but also a conduit for the manifestation of divine energies. In rituals and incantations, pagan practitioners harnessed the power of language to invoke the presence of deities, communicate with spirit realms, and bring about tangible changes in their lives and surroundings.

This sacred view of language is exemplified in the concept of “word magic,” which is found in various pagan traditions. By uttering specific phrases, chants, or prayers, practitioners believed they could tap into the creative force of the universe and influence the course of events. The deliberate and mindful use of language in pagan rituals was seen as a means of aligning oneself with the rhythms of nature and the will of the divine, fostering a deep sense of connection and purpose.

In contrast, egocentric and science-centric communities often approach language as a tool for asserting individual authority and advancing personal agendas. When language is wielded primarily for the purpose of self-aggrandizement or the manipulation of others, its sacred potential is diminished. The focus on individual achievement and the pursuit of objective truth can lead to a disconnection from the transformative power of words and a disregard for their impact on the collective psyche.

Moreover, the emphasis on scientific empiricism in modern societies can create a reductionist view of language, where words are stripped of their symbolic and metaphorical significance. When language is seen merely as a means of conveying factual information, its capacity to evoke emotional resonance, inspire imagination, and facilitate spiritual exploration is often overlooked. This narrow understanding of language can lead to a impoverishment of the human experience and a disconnection from the rich tapestry of meaning that words can weave.

Pagan communities, on the other hand, recognized that language was not only a tool for communication but also a means of participating in the unfolding of creation itself. By approaching language as a sacred act, they cultivated a deep reverence for the power of words and a keen awareness of the responsibility that comes with their use. This mindful engagement with language allowed pagan practitioners to tap into the transformative potential of speech and to use it as a vehicle for personal growth, communal bonding, and spiritual awakening.

Emergence of Language as the Birth of Gods

The origins of writing and religion are inextricably intertwined, with the development of early scripts playing a pivotal role in the conceptualization and veneration of divine entities. The earliest known forms of writing emerged around 3500-3000 BCE in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, taking the form of pictographic symbols etched onto clay tablets or carved into stone. These simple pictograms represented objects from the natural world – animals, plants, celestial bodies, and tools used in everyday life.

However, these pictographs held significance beyond their literal depictions. The very act of recording images onto a permanent surface demonstrated a human desire to document, memorialize, and ascribe meaning to their observations and experiences. Drawing a bison on a cave wall or tablet was an attempt to harness the power and life force of that being through symbolic representation.

As writing systems evolved becoming more abstract, so too did religious beliefs. The proto-cuneiform script of ancient Sumer transitioned pictographs into more stylized emblems and logographs around 3000 BCE. Simple depictions combined to convey complex metaphorical concepts. A star might represent the literal celestial body but also ideas like light, guidance, or divinity itself.

It was through this process of symbolic synthesis that the first recognized deities emerged in Mesopotamian religions like Sumerian and Akkadian mythology. Gods and goddesses were personifications of natural forces and human experiences – Ishtar the force of fertility and war, Enki the lord of wisdom and waters, Shamash the life-giving sun. Hieroglyphic writing in ancient Egypt followed a similar trajectory, with deities like Ra, Osiris, and Isis arising as emblematic representations of the sun, the underworld, and motherhood respectively.

In this way, the evolution of writing was inexorably tied to the development of religious beliefs and practices. As humans became more linguistically adept at combining simple symbols into complex metaphors, they manifested these metaphors into anthropomorphized deities. The creation of writing enabled the conception of cosmic beings and powers governing the mysteries of existence. Myths and religious traditions could now be formally recorded and passed down for generations.

While modern monotheistic faiths like Christianity, Islam and Judaism differ from the symbolic pagan pantheons in their core theological principles, they still bear the indelible markings of our preliterate, myth-making species. The shared similarities in creation stories, prophets, divine laws, and visions of the afterlife underscore the extent to which humans have always strived to make sense of the universe through storytelling and applying deific meaning to the forces of nature.

From the earliest pictographic etchings to the great tomes of canonical scripture, the desire to record, symbolize, personify and ultimately deify our experiences through the written word has remained a constant driving force throughout human civilization. The gods themselves are intrinsically worded beings – personifications of the very concepts writing allowed us to conceive.

“So I pulled the sun screen down and squinted and put the throttle to the floor. And kept on moving west. For West is where we all plan to go some day. It is where you go when the land gives out and the oldfield pines encroach. It is where you go when you get the letter saying: Flee, all is discovered. IT is where you go when you look down at the blade in your hand and see the blood on it. It is where you go when you are told that you are a bubble on the tide of empire. It is where you go when you hear that thar’s gold in them-thar hills. It is where you go to grow up with the country. It is where you go to spend your old age. Or it is just where you go.”

― Robert Penn Warren, All the King’s Men

JAMES HILLMAN: I was reading about this practice that the ancient Egyptians had of opening the mouth of the dead.1 It was a ritual and I think we don’t do that with our hands. But opening the Red Book seems to be opening the mouth of the dead.

SONU SHAMDASANI: It takes blood. That’s what it takes. The work is Jung’s “Book of the Dead.” His descent into the underworld, in which there’s an attempt to find the way of relating to the dead. He comes to the realization that unless we come to terms with the dead we simply cannot live, and that our life is dependent on finding answers to their unanswered questions.

JH: Their unanswered questions.

SS: We think we’re posing the questions but we’re not. The dead are animating us.

JH: But the questions . . . Jung says there that we think the figures we uncover in our dreams or in active imagination are the result of us, but he says we are the result of them. Our life should be derived from them. We just think of it wrong. We think whatever comes to us comes to us as something leftover from, as Freud said, Tagesrest, the residues of the day, images that are composite stuff, garbage from life. But Jung is saying these figures come to us in our dreams and even our thoughts derive from these figures, so the task would be uncovering the figures, which seems to be what the Red Book does. He allows the figures to speak, to show themselves. He even encourages them to.

SS: Descending into his own depths he finds images that, in a sense, have preceded him. It is a descent into human ancestry.

-Lament of the Dead

The Connection Between Death, Language, and Meaning

Death plays a pivotal role in the creation of meaning and the evolution of language. The very fact that we are mortal imbues the words we use with significance, as the language we speak is shaped by the collective experiences and wisdom of all those who have come before us. In this sense, language serves as a bridge between the living and the dead, allowing us to commune with the ghosts of our ancestors and keep their stories alive.

Philosopher and novelist Michael S. Judge argues that language, at its core, is a way of bringing the dead back to life, if only for a fleeting moment. When we speak or write, we are not only expressing our own thoughts and feelings but also channeling the voices of those who have passed on. This idea is reflected in the mythological figures associated with writing, secrecy, and death in various cultures, such as the psychopomp who guides souls to the underworld. Engaging with written language, in particular, connects us to the entire history of human expression and the metaphorical language that has evolved over millennia.

The work of theologian John Caputo further explores the relationship between death, language, and meaning. In “The Weakness of God,” Caputo argues that the vulnerability and mortality embodied in the death of Christ represents a deconstruction of traditional power structures and belief systems. Through this “weakness,” he suggests, new possibilities for authentic meaning and connection emerge. This idea can be extended to the role of death in the creation of meaning more broadly. It is precisely because we are mortal and vulnerable that our words and actions take on such profound significance.

The human confrontation with death, as explored by psychologist Ernest Becker in “The Denial of Death,” is a fundamental driving force behind our symbolic behavior and cultural achievements. Language itself can be seen as an attempt to transcend our mortality, to leave a lasting mark on the world that will endure long after we are gone. Every word we speak carries the echoes of those who have come before us, weaving their stories into the fabric of human history.

In “The Dominion of the Dead,” Robert Pogue Harrison argues that the dead continue to exert a powerful influence over the living through their presence in language, tradition, and cultural memory. Human civilization, he suggests, is a response to the inevitability of death, a way of keeping the memories and achievements of the deceased alive through our institutions, rituals, and histories. Language, in this context, becomes a sacred means of communing with our ancestors and honoring their legacy.

Harrison also points to the social calls and behaviors exhibited by animals such as elephants, dolphins, and primates in response to the death of a member of their group. He proposes that these mourning rituals and vocalizations may have been a precursor to the development of human language, as the need to express grief, offer comfort, and make sense of mortality drove the evolution of more complex communication. The awareness of death and the social rituals surrounding it, he argues, are central aspects of human culture that set us apart from other species.

The symbols and metaphors we use in language are layered with ancestral meaning, carrying the weight of the struggles, triumphs, and hard-won wisdom of countless generations. Every time we speak, we summon the ghosts of those who first gave life to these symbolic forms, engaging in an act of remembrance that defies the oblivion of death. As Caputo suggests, it is in this vulnerability and weakness that we find the strength to create meaning that transcends our mortal existence.

Even for those who do not subscribe to traditional religious beliefs, death itself can become a source of meaning and significance. The psychologist and spiritual teacher Ram Dass suggests that for the atheist, death becomes a form of “God” – the ultimate reality that gives weight and purpose to our lives. In the face of our own mortality, each word we speak or write becomes a defiant act of creation, an attempt to assert our presence in the world before we inevitably return to the void.

Ultimately, the connection between death, language, and meaning reminds us of the preciousness and fragility of our existence. By engaging with language as a living, sacred force, we can tap into the wisdom of those who have come before us, honor their memory, and create meaning that endures beyond our own brief moment in the sun. In the face of death, we find the courage to speak, to create, and to leave our mark on the world, ensuring that the voices of the past continue to resonate through the ages.

The Role of Nature in Pagan Spirituality

Paganism is deeply rooted in a profound reverence for the natural world, recognizing the earth, the cycles of the seasons, and the interconnectedness of all living things as sacred. This nature-based spirituality is fundamentally different from the more transcendent and otherworldly focus of later monotheistic religions. In pagan traditions, the divine is not seen as a distant, abstract entity, but as something that is immanent and manifest in the natural world itself.

For pagans, the earth is not merely a resource to be exploited, but a living, sentient being that is worthy of respect and veneration. The cycles of the seasons, the growth and decay of plants and animals, and the movements of the sun, moon, and stars are all seen as manifestations of the divine, imbued with sacred meaning and power. Pagan rituals and festivals often revolve around honoring these natural cycles and aligning human activities with the rhythms of the earth.

This deep connection to nature is reflected in the pantheons of pagan gods and goddesses, many of whom are associated with specific aspects of the natural world, such as the sun, the moon, the sea, or the forest. These deities are not seen as remote or abstract entities, but as personifications of the forces and energies that animate the cosmos, and as such, they are intimately connected to the lives and experiences of their human worshippers.

The relevance of pagan nature worship for contemporary environmental ethics and eco-spirituality movements cannot be overstated. In an age of ecological crisis, when the earth is threatened by climate change, habitat destruction, and species extinction, the pagan reverence for nature offers a powerful alternative to the instrumental and exploitative attitudes that have dominated modern industrial societies.

By recognizing the intrinsic value and sacredness of the natural world, paganism challenges us to develop a more harmonious and sustainable relationship with the earth, one based on respect, reciprocity, and reverence. The pagan emphasis on the interconnectedness of all life also resonates with contemporary scientific understandings of ecology and systems theory, which highlight the complex webs of relationships that sustain the biosphere.

Moreover, the pagan celebration of the earth’s cycles and the changing of the seasons can help to foster a sense of place and belonging, rooting individuals and communities in the rhythms and processes of the natural world. This connection to the earth can provide a sense of grounding and purpose in an age of rapid change and globalization, when many people feel disconnected from the natural world and from the sources of meaning and value in their lives.

The Social and Political Dimensions of Pagan Societies

In ancient pagan societies, religious beliefs and practices were deeply intertwined with social and political structures, shaping the ways in which communities were organized and power was legitimized. Pagan priesthoods, temples, and festivals played a crucial role in maintaining social cohesion and cultural identity, serving as focal points for communal life and shared values.

Pagan priesthoods were often closely associated with political authority, with kings and rulers deriving their legitimacy from their supposed divine mandates or connections to the gods. In some cases, such as in ancient Egypt or the Inca Empire, the ruler was seen as a living god or a divine intermediary, wielding both spiritual and temporal power. This close relationship between religion and politics helped to reinforce the social hierarchy and to justify the concentration of power in the hands of a small elite.

At the same time, pagan religions were often highly decentralized and localized, with each city, tribe, or region having its own distinctive pantheon of gods and goddesses, myths, and rituals. This decentralization allowed for a great deal of diversity and flexibility in religious practice, as well as a certain degree of tolerance for different beliefs and customs.

The role of pagan festivals and ceremonies in maintaining social cohesion cannot be overstated. These communal gatherings, often tied to the cycles of the agricultural year or the movements of the celestial bodies, brought people together in shared acts of worship, celebration, and renewal. They provided opportunities for social bonding, cultural transmission, and the reinforcement of group identity and solidarity.

However, the decentralized and localized nature of pagan religions also meant that they were vulnerable to external threats and pressures. The rise of Christianity and other monotheistic faiths, with their more centralized and hierarchical structures, posed a significant challenge to pagan societies. The Christian emphasis on a single, universal God and a unified church hierarchy was in many ways antithetical to the pluralistic and diverse nature of pagan beliefs and practices.

Moreover, the Christian demonization of pagan gods and goddesses as false idols or malevolent demons, and the aggressive proselytizing of Christian missionaries, led to the gradual erosion and suppression of pagan traditions in many parts of the world. The destruction of pagan temples, the persecution of pagan priests and practitioners, and the appropriation of pagan sites and symbols by the Christian church all contributed to the decline of paganism as a viable religious and social force.

The Suppression and Revival of Paganism

The rise of Christianity and other monotheistic religions had a profound impact on the history of paganism, leading to the suppression and marginalization of pagan beliefs and practices over the course of many centuries. The Christian church, in particular, sought to eradicate what it saw as the false and idolatrous religions of the pagan world, and to establish itself as the one true faith.

This process of suppression took many forms, from the destruction of pagan temples and the confiscation of pagan property, to the persecution and execution of pagan priests and practitioners. The early Christian emperors of Rome, such as Constantine and Theodosius, played a key role in this process, issuing edicts that banned pagan sacrifices and closed pagan temples, and later, declaring Christianity to be the official religion of the empire.

Even as Christianity became the dominant religion of Europe and the Mediterranean world, however, pagan beliefs and practices never entirely disappeared. Many pagan traditions were absorbed and transformed by the Christian church, with pagan gods and goddesses being reinterpreted as Christian saints and pagan festivals being co-opted and Christianized. This process of syncretism and appropriation allowed elements of paganism to survive and persist, even as the official structures and institutions of paganism were dismantled.

In the modern era, there has been a significant revival of interest in paganism, driven in part by a growing disenchantment with the dominant monotheistic religions and a desire for a more earth-centered and experiential form of spirituality. The Romantic movement of the 18th and 19th centuries played a key role in this revival, with its celebration of nature, emotion, and the imagination, and its fascination with ancient myths and folklore.

This Romantic fascination with paganism found expression in the works of writers, artists, and scholars, who sought to recover and reinterpret the lost wisdom of the pagan world. Figures such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Blake, and James Frazer helped to popularize pagan themes and ideas, and to create a new cultural space for the exploration of alternative spiritualities.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, this revival of paganism has taken on new forms and expressions, with the emergence of contemporary pagan and neo-pagan movements such as Wicca, Druidry, and Asatru. These movements seek to reconstruct and revitalize ancient pagan traditions, adapting them to the needs and concerns of the modern world.

Despite these challenges, the revival of paganism in the modern era represents a significant cultural and spiritual phenomenon, one that speaks to a deep human need for connection, meaning, and enchantment in an increasingly disenchanted world. By offering an alternative vision of the sacred, one that is rooted in the rhythms of the earth and the mysteries of the cosmos, paganism continues to inspire and transform the lives of countless individuals and communities around the world.

The Relationship Between Paganism and the Arts

Pagan myths, symbols, and themes have had a profound and enduring influence on art, literature, and music throughout history, serving as a rich source of inspiration for artists across cultures and time periods. From the epic poetry of Homer and Virgil to the paintings of Botticelli and the operas of Wagner, the pagan imagination has left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of the Western world.

In the ancient world, pagan myths and legends provided the foundation for much of the great literature and art of classical antiquity. The epic poems of Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are steeped in the language and imagery of Greek mythology, with gods and goddesses playing a central role in the unfolding of the narrative. Similarly, the plays of the Greek tragedians, such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, drew heavily on the mythic traditions of the pagan world, using them to explore timeless themes of fate, justice, and the human condition.

In the visual arts, pagan themes and symbols have been a constant source of inspiration for painters, sculptors, and architects throughout history. The great masterpieces of classical sculpture, such as the Venus de Milo and the Apollo Belvedere, are rooted in the pagan tradition of idealizing the human form as a reflection of divine beauty. Similarly, the frescoes and mosaics of ancient Rome and Pompeii are filled with scenes from pagan mythology, depicting gods and goddesses, heroes and monsters, in vivid and colorful detail.

In the Renaissance, the rediscovery of classical learning led to a renewed interest in pagan themes and motifs, which found expression in the works of artists such as Botticelli, Michelangelo, and Titian. Botticelli’s famous painting, The Birth of Venus, is a stunning example of this pagan revival, with its lush and sensuous depiction of the goddess of love emerging from the sea.

In the 19th century, the Romantic movement brought a new fascination with pagan themes and imagery, as artists and writers sought to tap into the primal and elemental forces of nature and the human psyche. The operas of Richard Wagner, with their grand and sweeping mythological narratives, are a prime example of this Romantic fascination with paganism, as are the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with their dreamy and ethereal depictions of pagan goddesses and nymphs.

The influence of paganism on the arts has continued into the modern era, with contemporary artists and writers drawing on pagan themes and symbols to explore new forms of spirituality and meaning. The works of writers such as Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, and Madeline Miller, and the films of directors such as Guillermo del Toro and Hayao Miyazaki, are all deeply indebted to the pagan imagination, with its rich tapestry of gods, monsters, and mythic archetypes.

Moreover, the pagan emphasis on the sacred power of art and creativity has had a profound impact on the way in which art is understood and valued in modern society. For pagans, art is not simply a form of entertainment or decoration, but a means of connecting with the divine, of tapping into the primal energies of the cosmos and the depths of the human soul. This view of art as a sacred and transformative force has inspired countless artists and writers throughout history, and continues to shape the way in which we understand the role and purpose of art in our lives.

Ultimately, the enduring influence of paganism on the arts is a testament to the power and resilience of the pagan imagination, and to the deep human need for mystery, beauty, and transcendence. By keeping alive the ancient stories, symbols, and traditions of the pagan world, artists and writers have helped to preserve and transmit the wisdom and insights of this rich and vital spiritual tradition, even in the face of centuries of suppression and marginalization.

A Comparative Analysis of Pagan and Monotheistic Worldviews

Pagan and monotheistic religions represent two fundamentally different ways of understanding the nature of the divine, the structure of the cosmos, and the place of humanity within it. While both traditions have shaped the course of human history and culture in profound ways, they are based on very different assumptions and values, which have significant implications for how individuals and societies understand themselves and their relationship to the world around them.

One of the most fundamental differences between paganism and monotheism is their respective views of the nature of the divine. Pagan traditions are typically polytheistic, recognizing a multiplicity of gods and goddesses who are associated with different aspects of the natural world and human experience. These gods and goddesses are often seen as embodiments of specific forces or energies, such as love, war, wisdom, or fertility, and are understood to be in constant interaction and conflict with one another.

In contrast, monotheistic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, believe in a single, supreme God who is the creator and sustainer of the universe. This God is typically understood to be transcendent and omnipotent, existing beyond the limitations of time and space, and is often associated with moral qualities such as justice, mercy, and love.

Another key difference between paganism and monotheism is their respective views of the relationship between the divine and the natural world. Pagan traditions often see the divine as immanent within nature, with gods and goddesses inhabiting trees, rivers, mountains, and other natural features. This animistic and pantheistic worldview emphasizes the sacredness and interconnectedness of all living things, and sees humanity as just one part of a larger web of life.

Monotheistic religions, on the other hand, typically see God as separate from and transcendent to the natural world, which is understood as a creation that is distinct from its creator. This dualistic worldview can sometimes lead to a more instrumental and exploitative view of nature, as something that exists primarily for human use and benefit.

The different views of time and history in pagan and monotheistic traditions are also significant. Pagan religions often have a cyclical view of time, with the cosmos understood to be in a constant state of birth, death, and regeneration. This cyclical view is reflected in the pagan calendar, with its seasonal festivals and celebrations tied to the rhythms of the natural world.

Monotheistic religions, in contrast, typically have a linear view of history, with time understood as a progression from creation to judgment day. This linear view is often associated with a belief in the importance of human moral agency and the idea of a divine plan or purpose for history.

These different worldviews have significant implications for how individuals and societies understand themselves and their place in the world. Pagan traditions, with their emphasis on the sacredness of nature and the interconnectedness of all life, can foster a sense of humility and reverence for the natural world, as well as a deep appreciation for the cycles of birth, death, and renewal that characterize all living systems.

Monotheistic traditions, with their emphasis on a single, transcendent God and the importance of human moral agency, can foster a sense of individual responsibility and purpose, as well as a belief in the possibility of progress and the ultimate triumph of good over evil.

At the same time, both pagan and monotheistic worldviews have their limitations and dangers. Pagan traditions can sometimes lead to a romanticization or idealization of nature, overlooking the harsh realities of disease, predation, and natural disasters. Monotheistic traditions can sometimes lead to a sense of human exceptionalism and a disregard for the intrinsic value of non-human life.

Ultimately, a comparative analysis of pagan and monotheistic worldviews highlights the diversity and complexity of human religious experience, and the ways in which different cultures and traditions have sought to make sense of the mysteries of existence. By understanding the strengths and limitations of both pagan and monotheistic perspectives, we can perhaps develop a more nuanced and inclusive view of the sacred, one that honors the wisdom of both traditions while also recognizing their historical and cultural specificity.

The Inevitability of Monotheism in a World with Technocratic Specialization

In a world characterized by technocratic specialization, neoliberal market structures, and increasing complexity in business and political organizations, the rise of monotheism as the dominant religious paradigm seems almost inevitable. As societies become more differentiated and hierarchical, with power concentrated in the hands of a small elite, the idea of a single, all-powerful God who rules over the universe becomes more appealing and more compatible with the prevailing social and economic order.

One of the key features of technocratic specialization is the division of labor and the fragmentation of knowledge into ever more narrow and specialized domains. In such a system, individuals are encouraged to focus on their specific area of expertise, rather than on the bigger picture or the interconnectedness of all things. This fragmentation of knowledge and experience can lead to a sense of alienation and disconnection from the natural world and from the larger community of life.

In this context, the idea of a single, transcendent God who exists outside of and above the natural world can provide a sense of unity and purpose that is lacking in a fragmented and specialized society. Monotheism, with its emphasis on a divine plan and the ultimate meaningfulness of human existence, can offer a sense of coherence and direction in a world that often seems chaotic and unpredictable.

Moreover, the hierarchical and centralized structure of monotheistic religions, with their emphasis on obedience to a single divine authority, is more compatible with the centralized and hierarchical structure of technocratic and neoliberal societies. In a world where power is concentrated in the hands of a few, the idea of a single, all-powerful God who demands obedience and submission from his followers becomes more attractive and more useful as a means of social control.

This is in contrast to the more decentralized and egalitarian structure of many pagan societies, where religious duties and responsibilities were often shared across different classes and occupations. In pagan societies, religious rituals and practices were often integrated into daily life and work, with different gods and goddesses associated with specific crafts, professions, and natural phenomena. This integration of religion and everyday life fostered a sense of interconnectedness and community that is often lacking in modern, specialized societies.

The rise of monotheism is also closely linked to the development of written language and the dissemination of religious texts. In pagan societies, religious knowledge and practices were often passed down orally, through myths, stories, and rituals. The development of writing allowed for the codification and standardization of religious beliefs and practices, and for the creation of sacred texts that could be studied and interpreted by religious authorities.

This process of codification and interpretation led to a more abstract and intellectual understanding of religion, one that was less grounded in direct experience and more focused on doctrinal purity and orthodoxy. The dissemination of religious texts also allowed for the spread of monotheistic ideas across vast distances and cultures, leading to the gradual displacement of local pagan traditions.

The concept of the numinous, as developed by the theologian Rudolf Otto, is also relevant here. Otto defined the numinous as the experience of the holy or the sacred as something mysterious, terrifying, and fascinating. In pagan societies, the numinous was often associated with specific places, objects, or natural phenomena, such as sacred groves, magical objects, or the movements of the stars and planets.

With the rise of monotheism, however, the numinous became increasingly associated with a single, transcendent God who was seen as the source of all holiness and mystery. This shift in understanding led to a more abstract and intellectualized conception of the sacred, one that was less grounded in direct experience and more focused on theological speculation and doctrinal purity.

The Impact of Technological and Modernizing Forces on Mental Illness and Psychosis

Just as the rise of technocratic specialization and neoliberal market structures has influenced the development of religious beliefs and practices, these same forces have also had a profound impact on the way we understand and experience mental illness, particularly psychosis and delusions.

In traditional pagan societies, mental illness was often understood in spiritual or supernatural terms, with individuals experiencing altered states of consciousness being seen as possessed by spirits, cursed by gods, or gifted with prophetic or shamanic abilities. These experiences were often integrated into the larger social and cultural context, with the community providing support and guidance to those undergoing such transformations.

With the rise of modern, scientific approaches to mental health, however, these traditional understandings have been largely displaced by medicalized and individualized models of mental illness. Psychosis and delusions are now seen primarily as symptoms of underlying brain disorders, to be treated with medication and therapy rather than through spiritual or community-based interventions.

This shift in understanding has been driven in part by the increasing specialization and professionalization of mental health care, with psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals claiming exclusive expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. This has led to a narrowing of the range of acceptable explanations and treatments for mental illness, with alternative or traditional approaches often being dismissed as unscientific or ineffective.

At the same time, the dominance of neoliberal market forces has led to the commodification of mental health care, with the pharmaceutical industry and private insurance companies playing an increasingly prominent role in shaping the way mental illness is understood and treated. This has led to a focus on individual responsibility and self-management of mental health, rather than on the social and structural factors that contribute to mental distress.

The impact of these forces on the experience of psychosis and delusions has been significant. In a world that is increasingly fragmented, specialized, and commodified, individuals experiencing altered states of consciousness may find themselves isolated and stigmatized, with few resources or support systems available to them. The medicalization of mental illness has also led to a narrowing of the range of acceptable experiences and expressions of distress, with those falling outside of conventional diagnostic categories being marginalized or pathologized.

Moreover, the dominance of neoliberal market forces has led to a focus on individual responsibility and self-management of mental health, with those experiencing psychosis or delusions being expected to take responsibility for their own recovery and well-being. This can lead to a sense of shame and self-blame, as well as a reluctance to seek help or support from others.

In this context, it is perhaps not surprising that the content of psychotic experiences and delusions has also changed over time. Whereas in traditional societies, these experiences often revolved around spiritual or supernatural themes, such as possession by spirits or communication with the divine, in modern societies they are more likely to revolve around themes of surveillance, persecution, and control by shadowy government agencies, corporations, or technological entities.

This shift in content reflects the changing nature of power and authority in modern societies, with the rise of the national security state, the increasing power of corporations, and the ubiquity of surveillance technologies all contributing to a sense of powerlessness and paranoia among those experiencing psychosis.

The fragmentation and specialization of knowledge in modern societies may also contribute to the development of delusions, as individuals struggle to make sense of a world that seems increasingly complex and unpredictable. In a world where expertise is highly specialized and compartmentalized, it can be difficult for individuals to develop a coherent and integrated understanding of reality, leading to the formation of idiosyncratic or bizarre beliefs.

The impact of social media and digital technologies on the experience of psychosis and delusions is also worth noting. In a world where individuals are constantly bombarded with information and stimuli from a variety of sources, it can be difficult to distinguish between reality and fantasy, leading to the development of delusions or paranoid ideation. Social media platforms, in particular, have been associated with the spread of conspiracy theories and other forms of misinformation, which can fuel delusional thinking among vulnerable individuals.

Moreover, the constant surveillance and monitoring of individuals through digital technologies, such as smartphones and social media, can contribute to a sense of paranoia and persecution among those experiencing psychosis. The knowledge that one’s every move and communication is being tracked and analyzed by powerful entities can be deeply unsettling, particularly for those who are already struggling with a fragile sense of reality.

In this context, it is clear that the way we understand and experience mental illness, particularly psychosis and delusions, is deeply influenced by the technological and modernizing forces that shape our world. While these forces have brought many benefits, such as advances in scientific understanding and treatment of mental disorders, they have also contributed to a narrowing of the range of acceptable experiences and expressions of distress, as well as a sense of isolation and stigmatization among those experiencing altered states of consciousness.

Many times in the past we have realized that it is our immediate intuitions that are imprecise: if we had kept to these we would still believe that the Earth is flat and that it is orbited by the sun.

Our intuitions have developed on the basis of our limited experience. When we look a little further ahead we discover that the world is not as it appears to us: the Earth is round, and in Cape Town their feet are up and their heads are down.

To trust immediate intuitions rather than collective examination that is rational, careful and intelligent is not wisdom: it is the presumption of an old man who refuses to believe that the great world outside his village is any different from the one which he has always known.

— Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, Carlo Rovelli

Psychosis, Conspiracy Theories, and Religious Belief in the Context of Scientific Progress

In the pursuit of objective truth and empirical knowledge, modern science has often sought to eliminate the divine and subjective aspects of human experience. By focusing solely on the measurable and quantifiable, this approach has relegated the intuitive, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of our existence to the realm of superstition or irrationality. As a result, the role of religion and spirituality as a means of understanding the world and our place within it has been increasingly marginalized.

This disenchantment of the world, as described by sociologist Max Weber (1922), has led to a sense of alienation and disconnection from the natural world and the deeper mysteries of existence. When the divine is stripped from our understanding of reality, we are left with a cold, mechanical universe devoid of meaning and purpose. This purely materialistic worldview can foster a sense of existential anxiety and despair, as individuals struggle to find a sense of belonging and significance in a world that seems indifferent to their existence.

Moreover, the repression of the intuitive and subjective aspects of human experience can lead to a range of psychological and social problems. When individuals are cut off from their inner world and denied the opportunity to explore the spiritual dimensions of their being, they may become more vulnerable to psychosis, delusions, and other forms of mental distress. This is reflected in the changing nature of psychotic experiences across different historical and cultural contexts, as documented in studies like those conducted by Stompe et al. (2006).

In the absence of a meaningful spiritual framework, individuals may also be more susceptible to conspiracy theories and other forms of irrational thinking. As Uscinski and Parent (2014) have noted, conspiracy theories tend to flourish in times of rapid social, economic, or technological change, as people seek explanations for complex or unsettling events. When the world seems chaotic and unpredictable, the allure of simple, all-encompassing explanations can be hard to resist, even if these theories are based on little more than speculation and conjecture.

The rise of a purely materialistic worldview has also had a profound impact on religious belief and practice. While some have argued that science and religion are fundamentally incompatible, others, like Ian Barbour (1997) and John Haught (1995), have suggested that they can inform and enrich each other. By recognizing the limitations of a purely empirical approach to understanding the world, and by acknowledging the value of subjective experience and intuitive knowledge, we can create a more holistic and integrative framework for exploring the mysteries of existence.

This integrative approach is essential for addressing the psychological and spiritual needs of individuals in an increasingly complex and rapidly changing world. By honoring the divine and subjective aspects of human experience, we can create a more balanced and nuanced understanding of reality, one that recognizes the importance of both reason and intuition, science and spirituality.

Furthermore, by cultivating a sense of connection to the natural world and the deeper dimensions of our being, we can foster a greater sense of meaning, purpose, and psychological resilience. This can help to mitigate the negative effects of psychosis, conspiracy theories, and other forms of irrational thinking, by providing individuals with a more stable and coherent framework for understanding their experiences and navigating the challenges of life.

Monotheistic and Polytheistic Consciousness

When his great Italian friend Michele Besso died, Einstein wrote a moving letter to Michele’s sister: ‘Michele has left this strange world a little before me. This means nothing. People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction made between past, present and future is nothing more than a persistent, stubborn illusion.’

— Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, Carlo Rovelli

The conscious objective mind and the unconscious symbolic dimension are not separate entities and that is what makes religion, spirituality, and subjective experience so frustrating to study. They are woven together and blended in a way that is partially homogenous and and partially heterogeneous, making our consciousness both a particle and a wave. Put more bluntly the conscious and unconscious mind are both separate and opposing and entirely blended in an inseparable way. The paradoxical nature of our consciousness is what makes paganism both hard to define and inevitable. Primitive pagans lived in a more conversational paradigm with the unconscious being a more actively acknowledged part of their experience. This is not wrong but also not the end of the progression of how we should integrate religion and pagan “gods” into our psyche, communities and culture.

We must acknowledge that science itself, despite its reliance on empirical observation and mathematical rigor, is ultimately a quest to reconcile the paradoxes that permeate our existence. While language, psychology, and philosophy grapple with paradox through the metaphorical fabric of the human mind, science seeks to untangle these knots through the language of mathematics and the systematic interrogation of nature’s mysteries.

The Double-Slit Experiment and the Paradox of Consciousness

The double-slit experiment, one of the most famous and perplexing experiments in the history of physics, has revealed the fundamental paradox of light’s nature as both a particle and a wave. This discovery has profound implications not only for our understanding of the physical world but also for our conception of human consciousness and the relationship between the conscious and unconscious mind.

Like the interference pattern that emerges in the double-slit experiment, the interplay between the conscious and unconscious creates a complex tapestry of experience, one that defies simple categorization or control. From one perspective, as W.H. Auden suggests, we are “lived through” by forces we cannot comprehend, our lives shaped by the unseen currents of the unconscious. In this view, our sense of autonomy is an illusion, a mere epiphenomenon of the deeper, more primal drives that animate our being.

Yet, from another vantage point, we are indeed separate, independent beings, capable of exerting our will and shaping our destinies through the power of conscious choice. This perspective emphasizes the role of personal agency, the belief that we are the masters of our own fate, even as we navigate the complex interplay of internal and external forces.

The truth, as with the nature of light, lies in the paradoxical unity of these seemingly contradictory aspects. Our conscious and unconscious minds are not separate entities but rather two facets of a single, indivisible whole. They are simultaneously distinct and interconnected, each influencing and shaping the other in a constant dance of creation and destruction, revelation and concealment.

This paradoxical relationship is reminiscent of the wave-particle duality of light, where the same entity can exhibit both wave-like and particle-like properties depending on the context and the mode of observation. In the same way, our conscious and unconscious minds are both fundamentally different and fundamentally the same, two aspects of a unified consciousness that transcends the limitations of linear thinking and binary oppositions.

By embracing this paradox, we can begin to navigate the complexities of our inner world with greater wisdom and compassion. We can learn to honor the power of our unconscious impulses and intuitions while also cultivating the clarity and focus of our conscious mind. We can recognize that our sense of self is not a fixed and immutable entity but rather a dynamic and ever-changing landscape, shaped by the constant interplay of light and shadow, reason and emotion, control and surrender.

By engaging in the delicate dance between the rational and the intuitive, the self-directed and the unconsciously driven, we open ourselves to a more profound understanding of our own nature and the world around us. It is in the reconciliation of these paradoxes, in the acceptance of the complex interplay between the conscious and unconscious, that we find the key to unlocking our full potential and navigating the rich, multifaceted landscape of our existence.

On Science and Consciousness in Paganism

In the history of scientific inquiry, we find that the most profound breakthroughs emerge not from pure logic or calculation, but from the fertile soil of human intuition and the unconscious mind. Visionaries like Einstein, Oppenheimer, and Kekulé did not stumble upon their revelations through empirical observation alone. No, their triumphs were preceded by flashes of insight, subjective leaps of imagination that dared to envision new possibilities beyond the boundaries of conventional thinking.

Einstein, for example, often spoke of the role of intuition and imagination in his scientific work. He once famously said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.” His groundbreaking theories of relativity were not simply the result of mathematical calculations, but were born from a deep intuitive understanding of the nature of space, time, and gravity.

Similarly, the chemist August Kekulé’s discovery of the structure of the benzene molecule is said to have come to him in a dream, in which he saw a snake biting its own tail, forming a ring. This intuitive leap allowed him to envision the circular structure of the benzene ring, a discovery that revolutionized the field of organic chemistry.

In quantum physics, the work of pioneers like Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg was deeply influenced by their philosophical and metaphysical insights. Bohr’s concept of complementarity, which held that the wave and particle nature of matter were both necessary for a complete understanding of reality, was not simply a mathematical formulation, but a profound intuitive insight into the nature of the universe.

Scientific discovery is not a purely rational or objective process, but is deeply intertwined with the subjective experiences and unconscious minds of the scientists themselves. The unconscious mind, with its vast reservoir of intuitive knowledge and symbolic associations, plays a crucial role in the creative process of scientific inquiry.

We must recognize that science is not a mere exercise in dispassionate rationality, but rather a means of translating the ineffable whispers of the unconscious into the tangible vernacular of empirical knowledge. For it is the unconscious forces of nature, imagination, and mysticism that serve as the primordial wellsprings of human understanding, the fertile ground from which all scientific inquiry ultimately springs.

Yet, in our modern, technocratic age, we have lost sight of this fundamental truth. Seduced by the allure of pure reason and the false promise of complete mastery over the natural world, we have severed our connection to the pagan roots that once infused our ancestors’ relationship with the cosmos. We have come to see ourselves as purely logical creatures, endowed with the gift of conscious thought, while denying the deeper wellsprings of our emotional and intuitive selves.

Through our economic systems, social programming, and bureaucratic structures, we have constructed an artificial edifice that obscures the paradoxical truths at the heart of our existence. We have forgotten that we are not disembodied intellects, but rather emotional beings first and foremost, creatures of soul and blood, inextricably intertwined with the rhythms and mysteries of the natural world.

In this sense, we are all pagans, whether we acknowledge it or not. The pagan essence that once guided our ancestors in their quest to understand the cosmos still burns within us, awaiting rediscovery and reintegration into our modern ways of being. For it is only by reconnecting with these pagan wellsprings, by embracing the paradoxes that define our existence and the primacy of the unconscious mind, that we can fully unlock the creative potential of human understanding.

Science, then, becomes a modern form of paganism, a means of unveiling the sacred mysteries that permeate the natural world and the depths of our own consciousness. By acknowledging the role of intuition, imagination, and the unconscious as the wellsprings of scientific discovery, we can reclaim our rightful place as creatures of paradox, ever seeking to reconcile the ineffable truths that lie at the heart of existence.

When we were only several hundred-thousand years old, we built stone circles, water clocks. Later, someone forged an iron spring. Set clockwork running. Imagined grid-lines on a globe. Cathedrals are like machines to finding the soul; bells of clock towers stitch the sleeper’s dreams together. You see; so we’ve always been on our way to this new place — that is no place, really — but it is real. It’s our nature to represent: we’re the animal that represents, the sole and only maker of maps. And if our weakness has been to confuse the bright and bloody colors of our calendars with the true weather of days, and the parchment’s territory of our maps with the land spread out before us — never mind. We have always been on our way to this new place — that is no place, really — but it is real.

-memory palace William Gibson

Timeline of the Development of Religion, Conspiracy Theories, and Prevailing Psychological Theories of Each Era

Ancient Period (3500 BCE – 500 CE):

Religion: Emergence of major religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, and precursors to Christianity and Islam. Development of religious texts, rituals, and practices.

Psychological Theories: Early philosophical ideas about the mind, soul, and human nature by thinkers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, but no formal psychological theories.

Conspiracy Theories/Folk Beliefs: Beliefs in supernatural forces, spirits, and the influence of gods or divine beings on human affairs. Folklore and myths explaining natural phenomena and human origins.

Types of Psychosis: Delusions of being possessed by spirits or divine beings, hearing voices from deities, ancestors or nature spirits, and experiencing visions of divine, mystical or spiritual nature. Psychotic experiences often integrated into religious and cultural beliefs.

Middle Ages (500 CE – 1500 CE):

Religion: Spread and dominance of Christianity and Islam, religious conflicts, the Crusades, and the persecution of heretics and non-believers. Monastic orders and scholasticism.

Psychological Theories: Limited development, with some philosophical ideas about the mind, soul, and human nature by thinkers like St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, influenced by religious doctrine.

Conspiracy Theories/Folk Beliefs: Beliefs in witchcraft, sorcery, demonic possession, and the devil’s influence on human affairs. Superstitions and folk remedies for ailments and misfortunes.

Types of Psychosis: Delusions of being possessed by demons or witches, hearing voices of saints, demons or spiritual entities, and experiencing visions of divine or infernal nature. Psychotic experiences often interpreted as demonic possession or witchcraft.

Renaissance and Early Modern Period (1500 CE – 1800 CE):

Religion: The Protestant Reformation challenged Catholic dominance, leading to religious wars and persecution. The Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment challenged traditional religious beliefs and authorities.

Psychological Theories: Early psychological theories emerged, such as the humorism theory by Galen, the association theory by John Locke, and the ideas of René Descartes on mind-body dualism.

Conspiracy Theories/Folk Beliefs: Beliefs in secret societies like the Rosicrucians and Freemasons, occult practices like alchemy and astrology, and supernatural phenomena like ghosts and vampires.

Types of Psychosis: Delusions of being persecuted by secret societies, religious authorities or the devil, hearing voices of angels, demons or deceased persons, and experiencing visions of mystical, occult or supernatural nature. Psychotic experiences still interpreted through the lens of religion and the supernatural.

19th Century (1800 CE – 1900 CE):

Religion: The rise of new religious movements like Mormonism and the Baha’i Faith, increasing secularization and the clash between religion and science, especially after Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Psychological Theories: The development of modern psychology, including Freudian psychoanalysis, the emergence of abnormal psychology, and the study of hypnosis and altered states of consciousness.

Conspiracy Theories/Folk Beliefs: Beliefs in the Illuminati, Freemasons, and other secret societies controlling world events. Spiritualism and the belief in contacting the dead through mediums.

Types of Psychosis: Delusions of being persecuted by secret societies or government agencies, hearing voices of deceased relatives, spirits or religious figures, and experiencing visions of mystical, occult or supernatural nature. The rise of spiritualism influenced some psychotic experiences.

Early 20th Century (1900 CE – 1950 CE):

Religion: Increasing religious pluralism, the rise of new religious movements like Scientology and the Nation of Islam, and the impact of world wars on religious beliefs and practices.

Psychological Theories: The development of behaviorism by John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner, Gestalt psychology by Max Wertheimer, and the continued influence of psychoanalysis. The study of shell shock and battle fatigue in soldiers.

Conspiracy Theories/Folk Beliefs: Beliefs in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, anti-Semitic conspiracies, and the influence of secret societies on world events like the Bolshevik Revolution. Beliefs in the paranormal and pseudoscientific practices like eugenics.

Types of Psychosis: Delusions of being persecuted by governments, political ideologies or racial/ethnic groups, hearing voices of deceased relatives, historical figures or ideological leaders, and experiencing visions of a political, ideological or racial nature. The trauma of war influenced some psychotic experiences.

Late 20th Century (1950 CE – 2000 CE):

Religion: The rise of new religious movements like the International Society for Krishna Consciousness and the Unification Church, increasing religious pluralism, and the influence of the counterculture movement on religious beliefs and practices.

Psychological Theories: The development of cognitive psychology by Aaron Beck and Albert Ellis, humanistic psychology by Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers, and the emergence of new therapies like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and family systems therapy.

Conspiracy Theories/Folk Beliefs: Beliefs in government cover-ups like the JFK assassination and the Moon landing hoax, the existence of extraterrestrial life and ancient aliens, and the influence of secret organizations like the Illuminati on world events.

Types of Psychosis: Delusions of being monitored or controlled by government agencies, extraterrestrials or shadowy organizations, hearing voices of aliens, government agents or advanced technologies, and experiencing visions of extraterrestrial, technological or futuristic nature. The rise of science fiction and space exploration influenced some psychotic experiences.

21st Century (2000 CE – Present):