Exploring the Intersection of Empiricism and Spirituality

When his great Italian friend Michele Besso died, Einstein wrote a moving letter to Michele’s sister: ‘Michele has left this strange world a little before me. This means nothing. People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction made between past, present and future is nothing more than a persistent, stubborn illusion.’

The relationship between science and spirituality has been a subject of intense debate and fascination for centuries. On one hand, science is often seen as a bastion of objectivity, relying on empirical observation and rational analysis to uncover the fundamental laws and mechanisms that govern the natural world. On the other hand, spirituality is often associated with subjective experience, intuitive wisdom, and a sense of the sacred or transcendent that lies beyond the reach of scientific inquiry.

At first glance, these two perspectives may seem fundamentally incompatible, with science representing a materialist worldview that reduces all phenomena to physical processes, and spirituality representing a metaphysical worldview that posits the existence of non-material realities and ways of knowing. However, a closer examination reveals that the relationship between science and spirituality is more complex and nuanced than this simple dichotomy suggests.

In this blog post, we will explore the myth of science and the science of myth, examining the reasons behind these two perspectives and the experiences of scientists who have bridged the gap between the empirical and the mystical. We will delve into the key principles and assumptions of the scientific materialist perspective, as well as the key insights and experiences that support the spiritual/metaphysical perspective. We will also consider the implications of this debate for our understanding of the nature of reality, the limits of human knowledge, and the potential for a more integrative and holistic approach to science and spirituality.

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.”

– Albert Einstein

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- The relationship between science and spirituality is complex and nuanced, with potential for integration and mutual enrichment.

- Scientific materialism emphasizes empirical observation, causal mechanisms, and peer review.

- The spiritual/metaphysical perspective argues for forms of knowledge beyond materialist paradigms, including subjective experience and perennial wisdom.

- Quantum mechanics has revealed counterintuitive aspects of reality, challenging classical notions of objectivity and causality.

- The measurement problem in quantum mechanics raises questions about the role of consciousness in shaping reality.

- Various interpretations of quantum mechanics (Copenhagen, Many-Worlds, Implicate Order) offer different perspectives on the nature of reality.

- Mystical traditions have described concepts that seem to parallel modern scientific discoveries.

- The study of complex systems and chaos theory reveals the interconnectedness and self-organizing nature of the universe.

- The concept of emergence challenges reductionist approaches to understanding reality.

- Many scientists throughout history have been inspired by mystical or spiritual experiences.

- The post-secular sacred perspective seeks to integrate scientific understanding with a sense of the numinous.

- Consciousness studies raise profound questions about the nature of subjective experience and its relationship to the physical world.

- Various thinkers and movements have explored the intersection of science, spirituality, and consciousness, including psychoanalysis, Eastern mysticism, and psychedelic research.

- An integrative approach to science and spirituality may offer new ways to address complex global challenges.

- The document presents a wide range of perspectives on consciousness, reality, and the potential for bridging scientific and spiritual worldviews.

The Scientific Materialist Perspective:”The scientific method is a way of thinking skeptically about empirical evidence. That’s all it is.”

– Carl Sagan

The scientific materialist perspective is based on the assumption that reality is fundamentally physical, and that all phenomena can be explained through empirical observation and causal mechanisms. This view has its roots in the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, which saw the emergence of a new way of understanding the world based on reason, experimentation, and mathematical analysis.

At the heart of the scientific materialist perspective is the principle of empirical observability. According to this principle, knowledge can only be obtained through the observation, measurement, and experimentation of physical phenomena that can be empirically verified. This means that scientific theories and hypotheses must be based on concrete, observable evidence, rather than on intuition, revelation, or other non-empirical sources of knowledge.

Another key principle of the scientific materialist perspective is the search for causal mechanisms. Science seeks to identify the natural laws and causal relationships that govern the behavior of physical systems, from the smallest subatomic particles to the largest structures in the universe. By understanding these causal mechanisms, scientists can make predictions about the behavior of natural phenomena, and develop technologies and interventions that harness these mechanisms for human benefit.

The scientific materialist perspective also emphasizes the importance of peer review and falsifiability. Scientific theories and discoveries must withstand rigorous scrutiny by other experts in the field, who can test and verify the claims being made. Moreover, scientific theories must be falsifiable, meaning that they must make predictions that can be tested and potentially disproven by empirical evidence. This ensures that science is a self-correcting process, in which false or incomplete theories are eventually weeded out and replaced by more accurate and comprehensive ones.

The success of the scientific materialist perspective can be seen in the tremendous technological and scientific advancements that have transformed the human condition over the past few centuries. From the development of modern medicine and transportation to the exploration of space and the understanding of the fundamental building blocks of matter, science has provided us with a wealth of knowledge and capabilities that would have been unimaginable to our ancestors.

Moreover, the scientific materialist perspective has demonstrated a remarkable explanatory power, accounting for a vast array of natural phenomena in a coherent and parsimonious manner. From the laws of motion and thermodynamics to the principles of evolution and genetics, science has provided us with a comprehensive framework for understanding the workings of the natural world, from the smallest scales to the largest.

However, despite its many successes, the scientific materialist perspective has also faced criticism and challenges from those who argue that it fails to capture the full complexity and richness of human experience and the nature of reality.

Evidence for the Scientific Materialist Perspective:”The day science begins to study non-physical phenomena, it will make more progress in one decade than in all the previous centuries of its existence.”

– Nikola Tesla

Empirical Observability:

The scientific method is based on the observation, measurement, and experimentation of physical phenomena that can be empirically verified. This provides a concrete, testable foundation for knowledge.

Causal Mechanisms:

Science focuses on identifying the causal mechanisms and natural laws that govern the physical world, allowing for predictable and repeatable phenomena.

Peer Review and Falsifiability:

Scientific theories and discoveries must withstand rigorous peer review and be falsifiable, ensuring a self-correcting process of knowledge generation.

Technological Advancements:

The materialist approach has enabled tremendous technological and scientific progress that has transformed the human condition, providing tangible benefits.

Explanatory Power:

Scientific explanations have been able to account for a vast array of natural phenomena, from the subatomic to the cosmic scale, in a coherent and parsimonious manner.

The Spiritual/Metaphysical Perspective:

The spiritual/metaphysical perspective, on the other hand, argues that there are forms of knowledge and reality that cannot be fully captured by the materialist paradigm. This view has its roots in the world’s great spiritual and philosophical traditions, which have long emphasized the importance of subjective experience, intuitive wisdom, and a sense of the sacred or transcendent that lies beyond the reach of ordinary perception and analysis.

One of the key arguments in favor of the spiritual/metaphysical perspective is the primacy of subjective experience. Proponents of this view argue that consciousness, qualia, and other first-person experiences cannot be fully reduced to physical processes or explained by materialist theories. They suggest that there is an irreducible subjective dimension to reality that must be taken into account in any comprehensive understanding of the world.

Another argument in favor of the spiritual/metaphysical perspective is the existence of what is often called “perennial wisdom” – a set of universal principles and insights that have been discovered and rediscovered across cultures and throughout history. These include ideas such as the unity and interconnectedness of all things, the presence of a divine or transcendent reality that underlies the physical world, and the possibility of direct experiential knowledge of this reality through practices such as meditation, contemplation, and prayer.

Proponents of the spiritual/metaphysical perspective also point to the ineffable aspects of human experience, such as love, beauty, meaning, and the sacred, as evidence of a dimension of reality that transcends the purely physical. They argue that these experiences have a quality of depth, significance, and transcendence that cannot be fully captured by scientific or materialist explanations.

Another criticism of the scientific materialist perspective from the spiritual/metaphysical point of view is the limits of reductionism. While reductionism has been a powerful tool for understanding complex systems by breaking them down into their component parts, critics argue that it fails to adequately address the emergent properties and complex, interconnected nature of reality. They suggest that a more holistic and integrative approach is needed, one that takes into account the ways in which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Finally, proponents of the spiritual/metaphysical perspective point to the transformative power of spiritual and contemplative practices as evidence of a dimension of reality that goes beyond the purely physical. Practices such as meditation, prayer, and ritual are claimed to foster profound shifts in consciousness, emotional healing, and a sense of connection to something greater than oneself. While these experiences may be difficult to quantify or explain in materialist terms, they are seen as a valid and important aspect of human experience that must be taken into account.

Evidence for the Spiritual/Metaphysical Perspective:

Subjective Experience:

Proponents argue that there are forms of knowledge and reality that cannot be fully captured by the materialist paradigm, such as consciousness, subjective experiences, and transcendent phenomena.

Perennial Wisdom:

Spiritual and metaphysical traditions often point to “perennial wisdom” – universal principles and insights that are repeatedly discovered across cultures and throughout history, suggesting a non-material foundation of reality.

Ineffable Aspects of Existence:

Aspects of human experience, such as love, beauty, meaning, and the sacred, are seen by some as transcending the purely physical and requiring a more holistic, non-material understanding.

Limits of Reductionism:

Critics of scientific materialism argue that it fails to adequately address the emergent properties and complex, interconnected nature of reality, which may require a more integrative, non-reductive approach.

Personal Transformation:

Spiritual and metaphysical practices, such as meditation, contemplation, and ritual, are claimed to foster profound personal transformation and access to non-ordinary states of consciousness.

“Despite the materialistic tendency to understand the psyche as a mere reflection or imprint of physical and chemical processes, there is not a single proof of this hypothesis. Quite the contrary, innumerable facts prove that the psyche translates physical processes into sequences of images which have hardly any recognizable connection with the objective process. The materialistic hypothesis is much too bold and flies in the face of experience with almost metaphysical presumption. The only thing that can be established with certainty, in the present state of our knowledge, is our ignorance of the nature of the psyche. There is thus no ground at all for regarding the psyche as something secondary or as an epiphenomenon; on the contrary, there is every reason to regard it, at least hypothetically, as a factor sui generis…”

-Jung, Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

Scientists Inspired by Mysticism:

Throughout history, there have been numerous examples of scientists who have drawn inspiration from mystical experiences or spiritual traditions in their work. These scientists have often found that their spiritual insights and experiences have provided them with new ways of understanding the natural world, and have led to groundbreaking discoveries and innovations in their fields.

One famous example is the chemist Friedrich August Kekulé, who is credited with discovering the structure of the benzene ring. According to legend, Kekulé had a dream in which he saw a snake biting its own tail, which inspired him to propose the circular structure of the benzene molecule. While the story may be apocryphal, it reflects the idea that creativity and insight often arise from non-rational or intuitive sources.

Another example is the physicist Niels Bohr, who was deeply influenced by Eastern mysticism and the concept of complementarity. Bohr believed that the wave-particle duality of quantum mechanics could be understood as a manifestation of the principle of complementarity, which holds that opposite or contrasting qualities can be equally necessary and true. This idea, which has its roots in Taoist and Buddhist thought, helped Bohr to develop a more holistic and integrated understanding of the quantum world.

The physicist Werner Heisenberg, another pioneer of quantum mechanics, was also influenced by Eastern philosophy and mysticism. Heisenberg was fascinated by the idea of the unity of all things, and saw in quantum mechanics a way of understanding the interconnectedness of the universe. He believed that the strange and paradoxical behavior of subatomic particles could be seen as a reflection of the ultimate nature of reality, which transcends the categories of classical physics.

Other examples of scientists who have drawn inspiration from mysticism include Wolfgang Pauli, who collaborated with the psychologist Carl Jung to explore the relationship between quantum physics and the collective unconscious; Max Planck, who believed that science and religion were complementary ways of understanding the universe; and Erwin Schrödinger, who was influenced by Vedantic philosophy and saw in quantum mechanics a way of understanding the unity of consciousness and matter.

List of Mystic Scientists

Friedrich August Kekulé:

The German chemist credited with discovering the structure of the benzene ring claimed to have had a vision of a snake biting its own tail, inspiring his circular model.

Niels Bohr:

The Danish physicist, a pioneer of quantum physics, was deeply influenced by Eastern mysticism and incorporated ideas from Taoism and Buddhism into his model of the atom.

Werner Heisenberg:

The German physicist, a key figure in quantum mechanics, was interested in the relationship between Eastern philosophy and the paradoxes of quantum theory.

Wolfgang Pauli:

The Austrian physicist, known for the Pauli exclusion principle, collaborated with psychoanalyst Carl Jung to explore the links between quantum physics and Jungian archetypes.

Max Planck:

The German theoretical physicist, considered the founder of quantum theory, believed that science and religion were not incompatible and saw his work as uncovering the fundamental laws set in place by God.

Albert Einstein:

While not directly inspired by mysticism, the renowned physicist had a deep appreciation for the “cosmic religious feeling” and believed that the pursuit of science was akin to a religious quest to uncover the harmony of the universe.

Erwin Schrödinger:

The Austrian physicist, a pioneer of quantum mechanics, was influenced by the ancient Hindu text Vedanta and incorporated ideas of consciousness and the oneness of the universe into his scientific worldview.

Srinivasa Ramanujan:

The renowned Indian mathematician claimed his remarkable mathematical insights came to him through visions of the Hindu goddess Namagiri.

Johannes Kepler:

The German astronomer and mathematician derived his three laws of planetary motion through a combination of meticulous observation and a belief in an underlying divine harmony guiding the planets.

Nikola Tesla:

The Serbian-American inventor claimed many of his revolutionary ideas came to him through visions and intuitions rather than methodical experiments, believing these insights were granted to him by the universe itself.

Rudolf Steiner:

The Austrian philosopher and esotericist developed the spiritual philosophy of anthroposophy, relying heavily on intuition and clairvoyance to inform his scientific and social theories.

Maria Prophetissa:

Considered one of the earliest known female alchemists, her alchemical insights were said to have come through mystical visions and communion with the divine.

George Washington Carver:

The American agricultural scientist and inventor derived many of his innovations through meditation and communing with nature, which he saw as a means of accessing divine knowledge.

The Implications for Science and Spirituality:

The debate between the scientific materialist perspective and the spiritual/metaphysical perspective has important implications for both science and spirituality. On the one hand, it challenges scientists to consider the limits of their methods and assumptions, and to be open to the possibility of non-material realities and ways of knowing. On the other hand, it challenges spiritual and religious traditions to engage with the findings and methods of science, and to be willing to subject their claims to empirical scrutiny and rational analysis.

One potential way forward is to develop a more integrative and holistic approach to science and spirituality, one that recognizes the value of both empirical observation and subjective experience, rational analysis and intuitive insight. This approach would seek to bridge the gap between the two perspectives, by finding ways of incorporating spiritual and mystical experiences into scientific theories and models, and by using scientific methods to investigate the effects and mechanisms of spiritual practices.

An example of this approach can be seen in the field of contemplative neuroscience, which uses brain imaging and other scientific techniques to study the neural correlates of meditation, prayer, and other spiritual practices. By showing how these practices can lead to measurable changes in brain function and structure, contemplative neuroscience provides a way of integrating spiritual experiences into a scientific framework, without reducing them to purely physical processes.

Another example is the study of psychedelic drugs, which have been shown to induce powerful mystical and transformative experiences in some individuals. While the use of these drugs remains controversial and legally restricted in many parts of the world, some scientists and therapists are exploring their potential as tools for psychological healing and spiritual growth, in a controlled and clinical setting.

At the same time, the debate between science and spirituality also highlights the importance of humility and openness on both sides. Scientists must be willing to acknowledge the limits of their methods and theories, and to be open to the possibility of phenomena that may not fit neatly into their existing paradigms. Spiritual and religious traditions, on the other hand, must be willing to engage with the findings and methods of science, and to be open to the possibility that some of their claims may need to be revised or reinterpreted in light of empirical evidence.

Ultimately, the goal of integrating science and spirituality is not to create a single, monolithic worldview that encompasses all of reality, but rather to foster a spirit of dialogue, exploration, and mutual enrichment between these two great human endeavors. By recognizing the value and limitations of both perspectives, and by being open to new ways of understanding and experiencing the world, we can create a more comprehensive and holistic approach to the big questions of existence, meaning, and purpose.

The Risks Of Spiritual Experience

The Challenges of Discernment:

While these examples demonstrate the potential for mystical experiences to inspire scientific breakthroughs, it is important to acknowledge the difficulty in distinguishing between genuine intuitive insights and other psychological phenomena such as traumatic reactions, bias, delusion, or psychosis.

These experiences often originate from the most ancient parts of the brain, such as the brainstem, which operates at a much faster speed than the more evolved frontal and mid-brain regions. This can lead to spiritual or intuitive experiences that seem to bypass or override rational thought and ego consciousness, making them feel profoundly real and meaningful to the individual.

However, this subjective certainty can also be a feature of delusional thinking, as seen in cult leaders who claim divine status despite evidence to the contrary. The case of Amy Carlson, leader of the Love Has Won cult, serves as a cautionary tale of how charismatic individuals can inspire false beliefs in others through their own grandiose delusions.

“The most beautiful and most profound experience is the sensation of the mystical. It is the sower of all true science.”

– Albert Einstein

The Strange and Counterintuitive Findings of Quantum Mechanics

Quantum mechanics, the branch of physics that describes the behavior of matter and energy at the atomic and subatomic scales, has yielded some of the most puzzling and counterintuitive findings in the history of science. These findings challenge our everyday notions of reality and have profound implications for our understanding of the nature of the universe.

One of the most famous and perplexing aspects of quantum mechanics is the concept of wave-particle duality. This principle states that all matter and energy can exhibit both wave-like and particle-like properties, depending on how it is observed or measured. For example, in the famous double-slit experiment, a beam of electrons or photons is fired through two parallel slits and observed on a screen behind the slits. When the particles are not observed, they behave like waves, creating an interference pattern on the screen. However, when the particles are observed, they behave like discrete particles, passing through one slit or the other and creating two distinct bands on the screen.

This dual nature of matter and energy is completely foreign to our everyday experience, where objects are either waves (like sound or light) or particles (like bullets or billiard balls), but never both at the same time. Yet at the quantum level, this is precisely what happens. Particles can behave like waves, and waves can behave like particles, depending on how they are observed or measured.

Another strange and counterintuitive finding of quantum mechanics is the concept of superposition. This principle states that a quantum system can exist in multiple states or configurations simultaneously, until it is observed or measured. The most famous example of this is the Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment, in which a cat is placed in a sealed box with a vial of poison and a radioactive source. If a single atom of the radioactive material decays, it will trigger a mechanism that shatters the vial and kills the cat. However, according to quantum mechanics, the cat is both alive and dead at the same time, until an observer opens the box and collapses the wave function, forcing the cat into one state or the other.

This idea of superposition is deeply counterintuitive, as it suggests that reality is not as definite or deterministic as we might assume. Instead, it implies that the universe is inherently probabilistic, and that multiple realities or possibilities can coexist until they are observed or measured.

A third strange and counterintuitive finding of quantum mechanics is the concept of entanglement. This principle states that two or more particles can become correlated or linked in such a way that their properties are interdependent, even if they are separated by vast distances. For example, if two entangled particles are created and then sent to opposite ends of the universe, measuring the properties of one particle will instantly affect the properties of the other, regardless of the distance between them.

This idea of entanglement violates our common sense notions of locality and causality, which assume that events can only affect each other if they are in close proximity and that causes must precede their effects. Yet at the quantum level, entanglement allows for instantaneous correlations and “spooky action at a distance,” as Einstein famously put it.

These strange findings of quantum mechanics have led to a host of philosophical and metaphysical questions about the nature of reality, the role of consciousness, and the relationship between mind and matter. Some scientists and philosophers have argued that quantum mechanics implies a fundamentally indeterministic and probabilistic universe, in which the future is not fully determined by the past. Others have suggested that quantum mechanics points to a deeper level of reality, in which the apparent randomness and uncertainty of the quantum world is merely a reflection of our limited understanding and measurement capabilities.

Still others have argued that quantum mechanics suggests a role for consciousness in shaping reality, as the act of observation or measurement appears to be necessary to collapse the wave function and force a quantum system into a definite state. This idea has led to various interpretations of quantum mechanics, such as the Copenhagen interpretation, which emphasizes the role of the observer in creating reality, and the many-worlds interpretation, which posits an infinite number of parallel universes, each corresponding to a different quantum possibility.

Regardless of which interpretation one favors, it is clear that quantum mechanics has profound implications for our understanding of the nature of reality, and that it challenges many of our deepest assumptions and intuitions about the world we live in. As we continue to explore the strange and counterintuitive realm of the quantum, we may be forced to revise our most basic concepts of space, time, matter, and consciousness, and to embrace a more holistic and integrated view of the universe.

The Measurement Problem and the Role of the Observer

One of the most persistent and puzzling aspects of quantum mechanics is the measurement problem, which arises from the apparent role of the observer in collapsing the wave function and determining the outcome of a quantum measurement. This problem has been at the center of debates about the interpretation of quantum mechanics for nearly a century, and it remains one of the most important unresolved issues in the foundations of physics.

The measurement problem can be illustrated by considering a simple quantum system, such as an electron with two possible spin states: up or down. According to quantum mechanics, the electron can exist in a superposition of these two states, with a certain probability of being measured in each state. However, when we actually measure the electron’s spin, we always find it in one definite state or the other, either up or down, with a probability that depends on the details of the measurement process.

The question then arises: what causes the wave function to collapse and the electron to assume a definite state? Is it the act of measurement itself, or is there some other mechanism at work? And what is the role of the observer in this process?

One view, known as the Copenhagen interpretation, holds that the act of measurement is what causes the wave function to collapse and the system to assume a definite state. According to this view, the observer plays a crucial role in creating reality, as it is the observer’s choice of measurement apparatus and procedure that determines which aspect of the system is observed and which possibilities are realized.

However, this view has been criticized for its subjectivity and its apparent dependence on the existence of a conscious observer. If the observer is necessary for the wave function to collapse, then what happens when there is no observer present? And how do we define an observer in the first place? Is it a human being, a measuring device, or something else entirely?

Another view, known as the many-worlds interpretation, seeks to avoid the measurement problem by positing that every quantum possibility is realized in some parallel universe. According to this view, when we make a measurement, we are merely observing one particular branch of the wave function, while all the other possibilities continue to exist in other branches. This interpretation eliminates the need for a collapse of the wave function and the role of the observer, but it leads to a proliferation of parallel universes and raises questions about the nature of probability and the meaning of existence.

A third view, known as the objective collapse theory, holds that the wave function collapses spontaneously and objectively, without the need for an observer or a measurement. According to this view, the collapse of the wave function is a fundamental and irreducible feature of reality, and it occurs randomly and unpredictably, with a probability that depends on the details of the system. This interpretation avoids the subjectivity and dependence on observers of the Copenhagen interpretation, but it introduces a new element of randomness and indeterminacy into the fabric of reality.

Regardless of which interpretation one favors, the measurement problem and the role of the observer remain central and unresolved issues in the foundations of quantum mechanics. They raise deep questions about the nature of reality, the relationship between the observer and the observed, and the limits of scientific knowledge and objectivity.

Some researchers have suggested that the measurement problem may be related to the nature of consciousness itself, and that understanding the role of the observer in quantum mechanics may require a deeper understanding of the relationship between mind and matter. Others have argued that the measurement problem may be resolved by developing new mathematical frameworks or physical theories that go beyond the current formalism of quantum mechanics.

Ultimately, the measurement problem and the role of the observer in quantum mechanics point to the deep interconnectedness and interdependence of all aspects of reality, from the smallest subatomic particles to the largest structures in the universe. They suggest that the act of observation and measurement is not a passive or neutral process, but rather an active and participatory one that shapes and creates the reality we experience.

As we continue to explore the strange and counterintuitive realm of quantum mechanics, we may need to develop new ways of thinking about the nature of reality and our place within it. We may need to embrace a more holistic and integrated view of the universe, one that recognizes the fundamental unity and interdependence of all things, and that sees the observer and the observed as two sides of the same coin. Only by grappling with these deep and perplexing questions can we hope to unlock the full potential of quantum mechanics and to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of reality itself.

Interpretations of Quantum Mechanics: Copenhagen, Many-Worlds, and Implicate Order

The strange and counterintuitive findings of quantum mechanics have led to a wide range of interpretations and philosophical debates about the nature of reality and the meaning of the quantum formalism. Among the most prominent and influential of these interpretations are the Copenhagen interpretation, the many-worlds interpretation, and the implicate order interpretation.

The Copenhagen interpretation, developed by Niels Bohr and his colleagues in the 1920s and 1930s, is one of the oldest and most widely accepted interpretations of quantum mechanics. According to this view, the wave function represents our knowledge or information about a quantum system, rather than an objective reality. The act of measurement is what causes the wave function to collapse and the system to assume a definite state, and the role of the observer is crucial in determining the outcome of the measurement.

The Copenhagen interpretation emphasizes the probabilistic and indeterministic nature of quantum mechanics, and it holds that the behavior of quantum systems is fundamentally different from that of classical systems. It also introduces the concept of complementarity, which states that certain properties of a quantum system, such as position and momentum, are mutually exclusive and cannot be measured simultaneously with arbitrary precision.

While the Copenhagen interpretation has been successful in accounting for many of the experimental results of quantum mechanics, it has also been criticized for its subjectivity and its reliance on the concept of a collapse of the wave function. Some researchers have argued that the idea of a collapse is ad hoc and unsatisfactory, and that it fails to provide a complete and consistent description of reality.

The many-worlds interpretation, proposed by Hugh Everett in the 1950s, seeks to avoid the problems of the Copenhagen interpretation by eliminating the need for a collapse of the wave function. According to this view, every quantum possibility is realized in some parallel universe, and the wave function never collapses. Instead, when we make a measurement, we are merely observing one particular branch of the wave function, while all the other possibilities continue to exist in other branches.

The many-worlds interpretation is attractive because it avoids the subjectivity and dependence on observers of the Copenhagen interpretation, and because it provides a deterministic and objective description of reality. However, it also leads to a proliferation of parallel universes and raises questions about the nature of probability and the meaning of existence. Some critics have argued that the many-worlds interpretation is untestable and unfalsifiable, and that it fails to provide a satisfactory explanation for the apparent uniqueness and definiteness of our experience.

The implicate order interpretation, developed by David Bohm in the 1970s and 1980s, is a more holistic and integrated approach to quantum mechanics that seeks to reconcile the apparent contradictions and paradoxes of the theory. According to this view, the universe is fundamentally interconnected and interdependent, and the apparent separateness and independence of objects and events is merely a superficial appearance.

Bohm proposed that beneath the level of the explicate order, which is the realm of ordinary experience and classical physics, there is a deeper level of reality called the implicate order, which is a holographic and dynamic whole that contains all possible states and configurations of the universe. The implicate order is constantly unfolding and enfolding, giving rise to the explicate order and the apparent separateness and definiteness of objects and events.

In Bohm’s view, the wave function is not a description of the state of a quantum system, but rather a description of the state of our knowledge about the system. The act of measurement is not a collapse of the wave function, but rather a process of unfolding and enfolding between the implicate and explicate orders, in which the observer and the observed are fundamentally interconnected and interdependent.

The implicate order interpretation provides a more unified and integrated view of reality that avoids many of the problems and paradoxes of the Copenhagen and many-worlds interpretations. It also has important implications for our understanding of consciousness, free will, and the nature of time and space.

However, the implicate order interpretation has also been criticized for its complexity and its reliance on speculative and metaphysical concepts. Some researchers have argued that it fails to provide a clear and testable mathematical formalism, and that it goes beyond the bounds of scientific inquiry and into the realm of philosophy and mysticism.

Ultimately, the debate over the interpretation of quantum mechanics is likely to continue for many years to come, as new experimental results and theoretical insights shed light on the nature of reality at the quantum scale. While the Copenhagen, many-worlds, and implicate order interpretations offer different perspectives on the meaning and implications of quantum mechanics, they all point to the fundamental interconnectedness and interdependence of all aspects of reality, and to the need for a more holistic and integrated approach to science and philosophy.

As we continue to explore the strange and counterintuitive realm of the quantum world, we may need to develop new ways of thinking about the nature of reality and our place within it. We may need to embrace a more participatory and creative view of the universe, one that recognizes the role of consciousness and subjectivity in shaping the world we experience. And we may need to develop new mathematical and conceptual frameworks that can bridge the gap between the quantum and classical realms, and that can provide a more complete and consistent description of reality at all scales.

Only by grappling with these deep and perplexing questions can we hope to unlock the full potential of quantum mechanics and to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of the universe and our place within it. And only by embracing a more holistic and integrated view of reality can we hope to find the answers to some of the most profound and enduring questions of science and philosophy.

Nevertheless, the convergence between quantum mechanics and Eastern spirituality points to the need for a more holistic and integrated approach to science and philosophy, one that recognizes the fundamental interconnectedness and interdependence of all aspects of reality, and that sees the pursuit of knowledge and understanding as a collaborative and participatory process, rather than a purely objective and detached one.

By embracing the insights and methods of both science and spirituality, we may be able to develop a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the nature of reality, one that honors both the empirical and the experiential, the rational and the intuitive, the material and the transcendent. Such an approach could help us to navigate the complex challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, and to create a more harmonious and sustainable relationship between ourselves, each other, and the world around us.

Experiments on the Subjective or Objective Nature of Reality

The Double-Slit Experiment

This classic experiment demonstrates the wave-particle duality of light and matter. When a beam of particles (such as electrons) is fired at a screen with two slits, it creates an interference pattern that suggests the particles are behaving like waves. However, when the particles are observed or measured at the slits, they behave like discrete particles, and the interference pattern disappears. This experiment shows that the act of observation can fundamentally change the behavior of quantum systems.

Schrödinger’s Cat

This thought experiment, proposed by Erwin Schrödinger, illustrates the concept of quantum superposition. Imagine a cat in a sealed box with a device that has a 50% chance of killing the cat within an hour. According to quantum mechanics, until the box is opened and the cat is observed, it exists in a superposition of being both alive and dead simultaneously. This experiment highlights the strange nature of quantum states and the role of observation in collapsing these states into definite outcomes.

The EPR Paradox and Bell’s Inequality

The Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox and Bell’s inequality demonstrate the phenomenon of quantum entanglement. In this experiment, two particles are entangled, meaning that their quantum states are correlated even if they are separated by large distances. Measuring the state of one particle instantly affects the state of the other, regardless of the distance between them. This “spooky action at a distance” violates the principles of locality and realism, and suggests that quantum mechanics is fundamentally non-local.

The Quantum Eraser Experiment

This experiment further explores the role of observation in quantum systems. In this setup, a double-slit experiment is performed, but the path of each particle is marked by a “which-path” detector. When the path information is recorded, the interference pattern disappears. However, if the path information is “erased” before the particles reach the screen, the interference pattern reappears. This experiment shows that the act of erasing or preserving path information can retroactively affect the behavior of the particles.

The Delayed-Choice Experiment

This experiment, first proposed by John Wheeler, challenges our notions of causality and time in quantum systems. In this setup, a quantum system (such as a photon) is given the “choice” to behave like a wave or a particle, but this choice is made after the photon has already passed through the apparatus. The delayed choice can retroactively determine the behavior of the photon, suggesting that the future can affect the past in quantum systems.

The Quantum Zeno Effect

This phenomenon occurs when a quantum system is repeatedly measured or observed. In the quantum Zeno effect, frequent measurements can “freeze” the evolution of a quantum state, preventing it from changing or decaying. This effect highlights the role of measurement in quantum systems and the way in which observation can actively influence the behavior of quantum entities.

The Work of Fritjof Capra, Gary Zukav, and David Bohm

The idea of a convergence between quantum mechanics and Eastern spirituality has been explored by a number of influential thinkers and writers, including Fritjof Capra, Gary Zukav, and David Bohm.

Fritjof Capra, a physicist and systems theorist, is perhaps best known for his 1975 book “The Tao of Physics,” in which he argued that there are deep parallels between the worldview of modern physics and the philosophical and spiritual traditions of the East, particularly Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. Capra suggested that the findings of quantum mechanics, such as the wave-particle duality, the uncertainty principle, and the role of the observer in shaping reality, are strikingly similar to the ideas found in these ancient wisdom traditions, which emphasize the unity and interdependence of all things, the illusory nature of the material world, and the primacy of consciousness in the creation of reality.

Capra’s work helped to popularize the idea of a “new paradigm” in science and philosophy, one that would integrate the insights of modern physics with the perennial wisdom of the world’s spiritual traditions. He argued that such a paradigm shift was necessary in order to address the complex challenges facing humanity in the modern world, from environmental degradation and social inequality to the existential threats posed by nuclear weapons and other advanced technologies.

Gary Zukav, a former Green Beret and Harvard graduate, is another influential figure in the popularization of the convergence between quantum mechanics and Eastern spirituality. In his 1979 book “The Dancing Wu Li Masters,” Zukav explored the philosophical implications of quantum physics, and argued that the findings of modern science were pointing towards a new understanding of reality that was more in line with the teachings of Eastern mysticism than with the mechanistic worldview of classical physics.

Zukav’s book, which became a bestseller and a cultural touchstone, helped to bring the ideas of quantum mechanics and Eastern philosophy to a wider audience, and to spark a conversation about the nature of reality and the role of consciousness in shaping our experience of the world. He argued that the strange and counterintuitive findings of quantum mechanics, such as the observer effect and the uncertainty principle, suggested that the traditional Western view of a purely objective and deterministic universe was no longer tenable, and that a more participatory and creative understanding of reality was needed.

David Bohm, a physicist and philosopher, is perhaps the most influential figure in the development of a more integrative and holistic approach to science and spirituality. Bohm, who worked closely with Einstein and other leading scientists of his day, was deeply interested in the philosophical implications of quantum mechanics, and in the ways in which the findings of modern physics could be reconciled with the insights of Eastern mysticism and other wisdom traditions.

In his book “Wholeness and the Implicate Order,” published in 1980, Bohm proposed a new model of reality that he called the “implicate order,” which he saw as a deeper level of reality that underlies the apparent separateness and independence of the material world. According to Bohm, the implicate order is a holographic and dynamic whole that contains all possible states and configurations of the universe, and that is constantly unfolding and enfolding, giving rise to the “explicate order” of ordinary experience.

Bohm argued that the implicate order could provide a framework for understanding the relationship between consciousness and matter, and for bridging the gap between science and spirituality. He suggested that consciousness is not a product of the brain or the material world, but rather a fundamental aspect of reality that is intimately connected with the implicate order. Bohm’s work has had a profound influence on the development of integrative and holistic approaches to science and philosophy, and has inspired a new generation of thinkers and researchers to explore the frontiers of human knowledge and experience.The

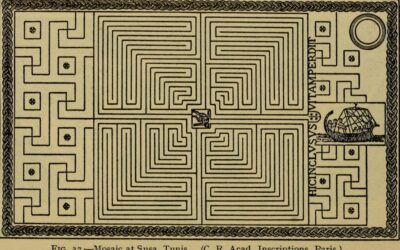

Mystical Traditions and Their Prescient Descriptions of Scientific Processes

Throughout history, various mystical and spiritual traditions have offered descriptions and metaphors that seem to preempt or parallel scientific processes and concepts, often in ways that the originators of these traditions could not have known based on the technology and scientific understanding available to them at the time. These prescient descriptions suggest that the mystical and spiritual experiences of these individuals may have provided them with intuitive glimpses into the fundamental nature of reality, which were then articulated through the language and symbolism of their respective traditions.

Kabbalah and the Concept of God as a Verb

One striking example of this phenomenon can be found in the Jewish mystical tradition of Kabbalah, particularly in its conception of God as a verb rather than a noun. In Kabbalah, God is understood not as a static, unchanging entity, but as a dynamic process of creation and transformation, constantly unfolding and evolving in response to the actions and choices of human beings.

This conception of God as a verb bears a remarkable resemblance to the modern scientific understanding of the universe as a vast, interconnected web of energy and information, constantly changing and evolving over time. The idea that the divine is not a fixed, eternal substance, but rather a dynamic, creative process, seems to anticipate the insights of quantum physics and complexity theory, which emphasize the inherent indeterminacy and potentiality of the natural world.

The Kabbalistic Tree of Life and the Interconnectedness of All Things

Another Kabbalistic concept that seems to anticipate modern scientific ideas is the Tree of Life, a symbolic representation of the divine emanations and the structure of the universe. The Tree of Life consists of ten “sefirot” or spheres, each representing a different aspect of the divine nature, and connected by a series of paths or channels.

The Tree of Life has been interpreted by some as a metaphor for the interconnectedness and interdependence of all things, with each sefirah representing a different level or dimension of reality, from the most abstract and spiritual to the most concrete and material. This idea of a holographic, fractal universe, in which each part contains the whole and the whole is reflected in each part, seems to anticipate the insights of modern physics and systems theory.

Indra’s Net and the Holographic Nature of Reality

In Buddhist philosophy, the concept of Indra’s Net offers a similar vision of the interconnectedness and interdependence of all things. Indra’s Net is described as a vast, infinite web of jewels, each reflecting and containing the image of all the others. This metaphor suggests that each individual phenomenon or entity in the universe is intimately connected to and reflective of all others, and that the boundaries between self and other, subject and object, are ultimately illusory.

The concept of Indra’s Net bears a striking resemblance to the holographic model of the universe proposed by physicist David Bohm, which suggests that the universe is a vast, interconnected whole, with each part containing information about the whole, and the whole being enfolded within each part. This holographic principle has been used to explain a wide range of phenomena, from the nonlocal effects of quantum entanglement to the nature of consciousness itself.

The Taoist Concept of Wu Wei and the Principle of Least Action

In Taoist philosophy, the concept of “wu wei” or “non-action” refers to a state of effortless, spontaneous action that is in harmony with the natural flow of the universe. This idea of acting without acting, of allowing things to unfold naturally without force or resistance, seems to anticipate the principle of least action in physics, which states that physical systems tend to evolve along the path of least resistance or effort.

The principle of least action has been used to explain a wide range of phenomena in physics, from the motion of planets and particles to the behavior of light and sound waves. The idea that the universe tends to follow the path of least resistance suggests a kind of inherent intelligence or optimization in the fabric of reality, which seems to parallel the Taoist vision of a harmonious, self-organizing cosmos.

The Vedic Concept of Maya and the Illusion of Separation

In Hindu philosophy, the concept of “maya” refers to the illusory nature of the material world, which is seen as a veil or screen that obscures the true nature of reality. According to this view, the apparent separation and diversity of the world is ultimately an illusion, and the true nature of reality is a unified, undifferentiated whole.

This idea of the world as an illusion or projection of consciousness seems to anticipate the insights of modern neuroscience and cognitive psychology, which suggest that our perception of the world is a construction of the brain, based on incomplete and ambiguous sensory data. The idea that the boundaries between self and other, subject and object, are ultimately illusory seems to parallel the insights of quantum physics, which challenge the classical notion of a clear distinction between observer and observed.

The Sufi Concept of the Unity of Being and the Interconnectedness of All Things

In Islamic mysticism or Sufism, the concept of “wahdat al-wujud” or the “unity of being” refers to the idea that all of existence is a manifestation of a single, divine reality. According to this view, the apparent diversity and multiplicity of the world is ultimately an illusion, and the true nature of reality is a unified, undifferentiated whole.

This idea of the unity of being seems to anticipate the insights of modern physics and systems theory, which emphasize the interconnectedness and interdependence of all things. The idea that the universe is a vast, interconnected web of relationships and processes, rather than a collection of separate, independent entities, seems to parallel the Sufi vision of a unified, all-encompassing divine reality.Alchemy and the

Transformation of Matter: Validating Alchemical Assumptions through Modern Science

The ancient practice of alchemy, which sought to transform base metals into gold, has often been dismissed as a pseudoscience or a mere symbolic and metaphorical pursuit. However, recent scientific discoveries have shed new light on the alchemical tradition, revealing that some of its assumptions about the nature of matter and the possibility of elemental transformation may have been more accurate than previously thought.

While modern chemistry has discredited the idea of literally transmuting one element into another, the alchemical concept of matter being composed of fundamental building blocks that can be manipulated and transformed has been validated by our current understanding of atomic structure. The discovery of subatomic particles such as protons, neutrons, and electrons has shown that the elements are not immutable and indivisible, but rather are composed of smaller, more fundamental components that can be rearranged and recombined.

The process of nuclear transmutation, in which one element is transformed into another through the addition or removal of protons, bears a striking resemblance to the alchemical goal of transmuting base metals into gold. While this process is not economically viable and requires advanced technology, it demonstrates that the fundamental idea behind alchemy – the ability to transform matter at the elemental level – is not entirely without merit.

Moreover, the alchemical emphasis on the purification and refinement of matter through a series of chemical processes can be seen as an early precursor to modern ideas about chemical reactions and the role of energy in the transformation of substances. The alchemists recognized that the elements were not static and unchanging, but rather were dynamic and reactive, capable of being transformed through the application of heat, light, and other forms of energy.

This idea has been validated by our modern understanding of chemical bonding and the role of electrons in determining the properties and behavior of elements. We now know that the stability and reactivity of an element depend on the configuration of its outermost electrons, and that by adding, removing, or rearranging these electrons, we can alter the chemical properties of a substance and induce chemical reactions.

In this sense, the alchemical concept of matter as a dynamic and transformative substance, capable of being purified and refined through a series of energetic processes, can be seen as a prescient anticipation of modern ideas about chemical bonding, reactivity, and the role of energy in the transformation of matter.

Of course, it would be a mistake to overstate the scientific accuracy or validity of alchemical ideas and practices. Much of what the alchemists believed and practiced was based on superstition, subjective projection onto objective realities, and a lack of genuine empirical knowledge about the nature of matter and energy. However, by recognizing the kernel of truth and insight that lies at the heart of the alchemical tradition, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the human capacity for intuitive and imaginative thinking, even in the absence of formal scientific knowledge.

The Neuroscience of Intuition and Unconscious Pattern Recognition

The Structure and Function of the Brain

The human brain is an incredibly complex and sophisticated organ, responsible for all aspects of our perception, cognition, emotion, and behavior. In order to understand the neuroscience of intuition and unconscious pattern recognition, it is important to first consider the basic structure and function of the brain.

The Brainstem: The Ancient Seat of Survival Instincts

The brainstem is the oldest and most primitive part of the brain, responsible for regulating basic survival functions such as breathing, heart rate, and alertness. It is also involved in processing sensory information and generating rapid, unconscious responses to potential threats or opportunities.

The brainstem is composed of three main structures: the midbrain, pons, and medulla oblongata. These structures work together to maintain homeostasis, or the stable internal environment necessary for survival. They also play a key role in generating instinctual behaviors, such as the fight-or-flight response, that can override conscious control in situations of extreme stress or danger.

The Limbic System: Emotion, Memory, and Intuition

The limbic system is a group of interconnected brain structures that are involved in emotion, motivation, and memory. It includes the amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, among other regions.

The amygdala is particularly important for the processing of emotionally salient stimuli, such as faces, social cues, and potential threats. It is involved in the formation and storage of emotional memories, and can generate rapid, unconscious responses to perceived dangers or opportunities.

The hippocampus, on the other hand, is critical for the formation and consolidation of declarative memories, or memories of facts and events. It works in concert with the amygdala to imbue these memories with emotional significance, and to allow for their rapid retrieval in relevant situations.

Together, the structures of the limbic system form the neural basis for intuition, or the ability to make rapid, unconscious judgments based on prior experience and emotional associations. They allow us to quickly assess the emotional and motivational significance of a situation, and to generate appropriate responses based on our past experiences and current goals.

The Neocortex: Higher-Order Thinking and Rational Decision Making

The neocortex is the most recently evolved part of the brain, and is responsible for higher-order cognitive functions such as language, abstract reasoning, and conscious decision making. It is divided into four main lobes: the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes.

The frontal lobe, in particular, is critical for executive function, or the ability to plan, organize, and regulate behavior in pursuit of long-term goals. It is involved in tasks such as working memory, attention, and impulse control, and allows us to override automatic or habitual responses in favor of more deliberate, rational decision making.

The parietal lobe is involved in processing sensory information and integrating it with motor commands, while the temporal lobe is important for language processing and semantic memory. The occipital lobe, meanwhile, is primarily involved in visual processing and perception.

Together, the various regions of the neocortex allow for the kind of conscious, deliberative thinking that we typically associate with human intelligence and rationality. They provide the neural basis for our ability to reason, plan, and make decisions based on a careful weighing of evidence and potential outcomes.

One of the key features of the lower brain regions, such as the brainstem and limbic system, is their ability to process information and generate responses at incredibly high speeds, often outside of conscious awareness.

The Rapid Response of the Brainstem

The brainstem, in particular, is capable of processing sensory information and generating motor responses in a matter of milliseconds. This rapid processing is critical for survival, as it allows us to quickly detect and respond to potential threats or opportunities in our environment.

For example, if we hear a loud noise or see a sudden movement in our peripheral vision, the brainstem can generate an immediate startle response, causing us to flinch or duck before we even have time to consciously process what is happening. This kind of rapid, reflexive response can mean the difference between life and death in situations of extreme danger.

he Role of the Amygdala in Threat Detection and Emotional Memory

The amygdala, too, is capable of processing emotional stimuli at incredibly high speeds, often before we are even aware of what we are seeing or feeling. This rapid emotional processing is thought to be an evolutionary adaptation, allowing us to quickly detect and respond to potential threats or opportunities in our environment.

For example, if we see a face with a fearful expression, the amygdala can generate an immediate emotional response, causing us to feel afraid or anxious before we even have time to consciously process what we are seeing. This kind of rapid emotional response can help us to avoid danger or to seize opportunities in social situations.

The amygdala is also involved in the formation and storage of emotional memories, allowing us to quickly retrieve past experiences that are relevant to our current situation. This can be adaptive, as it allows us to learn from our mistakes and to avoid repeating them in the future. However, it can also lead to the formation of traumatic or maladaptive memories, which can have long-lasting effects on our emotional and behavioral responses.

The Importance of Implicit Memory in Intuitive Decision Making

Implicit memory, or memory that is not consciously accessible, plays a key role in intuitive decision making. Unlike explicit memory, which involves the conscious recollection of facts and events, implicit memory operates outside of awareness, allowing us to draw on past experiences and associations without even realizing it.

For example, when we make a snap judgment about whether someone is trustworthy or not, we may be drawing on implicit memories of past experiences with similar individuals, even if we cannot consciously recall those experiences. Similarly, when we have a “gut feeling” about a particular course of action, we may be drawing on implicit memories of past successes or failures in similar situations.

The speed and efficiency of implicit memory processing is thought to be one of the key advantages of intuitive decision making. By allowing us to quickly access relevant past experiences and associations, implicit memory can help us to make rapid, accurate judgments in complex or ambiguous situations.

Unconscious Pattern Recognition and Intuition

Another key feature of the lower brain regions is their ability to unconsciously detect patterns and regularities in sensory input, and to use these patterns to generate intuitive judgments and decisions. The unconscious mind is vastly more powerful and efficient than the conscious mind, capable of processing enormous amounts of information in parallel and generating complex associations and inferences without our even being aware of it. This unconscious processing is thought to be the basis for many of our intuitive judgments and decisions, as well as for our ability to learn and adapt to new situations. By constantly monitoring our environment for patterns and regularities, the unconscious mind can help us to make sense of complex or ambiguous stimuli, and to generate rapid, accurate responses based on our prior experiences and knowledge.

Implicit learning, or learning that occurs without conscious awareness or intent, is thought to play a key role in skill acquisition and the development of expertise. Unlike explicit learning, which involves the conscious memorization of facts and procedures, implicit learning allows us to gradually absorb the patterns and regularities of a particular domain or activity, and to develop intuitive expertise over time.

For example, when we learn to play a musical instrument or to speak a new language, we are not consciously memorizing every note or every grammatical rule. Rather, we are gradually absorbing the patterns and regularities of the domain through repeated exposure and practice, and developing an intuitive sense of what “feels right” or “sounds right” in a given context.

This kind of implicit learning is thought to be particularly important in domains where there are many complex, interrelated variables to consider, and where conscious, rule-based reasoning may be too slow or cumbersome to be effective. In these situations, the unconscious mind can help us to quickly identify relevant patterns and generate appropriate responses, even if we cannot consciously articulate the reasons for our decisions.

The Relationship Between Intuition and Creativity

Intuition is also thought to play a key role in creativity and innovation, allowing us to generate novel ideas and solutions by drawing on unconscious associations and patterns.

When we engage in creative problem solving or brainstorming, we are often encouraged to “think outside the box” or to “let our minds wander” in order to generate new and original ideas. This kind of divergent thinking is thought to rely heavily on the unconscious mind, which can help us to make connections and associations that we might not have consciously considered.

Similarly, many creative individuals report that their best ideas often come to them suddenly and unexpectedly, as if “out of nowhere.” This kind of intuitive insight is thought to be the result of unconscious processing, which can help us to identify novel patterns and connections that we might not have consciously noticed.

The Challenges of Discernment

While intuition and unconscious pattern recognition can be powerful tools for decision making and problem solving, they are not infallible, and can sometimes lead us astray. One of the key challenges of relying on intuition is the difficulty of discerning between genuine insights and mere hunches or biases.

Distinguishing Between Intuition, Trauma and Instinct

One potential source of confusion is the difference between intuition and instinct. While both involve rapid, unconscious processing, instincts are innate, hardwired responses to specific stimuli, while intuitions are learned, context-dependent judgments based on prior experience and knowledge.

For example, the fight-or-flight response is an instinctual reaction to perceived threats, triggered by the brainstem and limbic system. In contrast, a chess master’s intuition about the best move to make in a particular position is the result of years of practice and experience, and is dependent on the specific context of the game.

Distinguishing between intuition and instinct can be difficult, as both can feel sudden and automatic. However, one key difference is that instincts are generally more rigid and inflexible, while intuitions are more adaptable and context-dependent.

The Influence of Bias and Heuristics on Intuitive Judgments

Another challenge of relying on intuition is the potential for bias and heuristics to distort our judgments. Heuristics are mental shortcuts or “rules of thumb” that we use to make rapid, efficient decisions in complex or uncertain situations. While heuristics can be useful in many contexts, they can also lead to systematic biases and errors in judgment.

For example, the availability heuristic is the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events that are easily remembered or imagined, while underestimating the likelihood of events that are less salient or memorable. This can lead us to make inaccurate judgments about risk and probability, based on our prior experiences and associations.

Similarly, confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out and interpret information in a way that confirms our existing beliefs and assumptions, while ignoring or discounting evidence that contradicts them. This can lead us to make intuitive judgments that are based more on our preconceptions than on objective reality.

The Risks of Unchecked Intuition in Decision Making

Given the potential for bias and error in intuitive judgments, it is important to recognize the risks of relying too heavily on intuition in decision making, particularly in high-stakes or consequential situations.

For example, in medical diagnosis, relying solely on intuition or “gut feelings” can lead to missed diagnoses or inappropriate treatments, with potentially serious consequences for patient outcomes. Similarly, in business or policy decisions, unchecked intuition can lead to flawed strategies or unintended consequences, with significant financial or social costs.

To mitigate these risks, it is important to balance intuition with more deliberative, analytical modes of thinking, and to subject intuitive judgments to rigorous testing and validation. This may involve seeking out additional data or perspectives, considering alternative hypotheses or scenarios, and explicitly examining assumptions and biases.

The Potential for Integrating Intuition and Rational Thinking

Despite the challenges and risks of relying on intuition, there is also significant potential for integrating intuitive and rational modes of thinking in a complementary and synergistic way. In many complex or uncertain situations, a purely analytical approach may be insufficient or impractical, due to the sheer number of variables and potential outcomes to consider. In these cases, intuition can provide a valuable starting point or “gut check” for generating hypotheses or identifying promising avenues for further exploration.

At the same time, rational analysis can help to refine and validate intuitive judgments, by subjecting them to rigorous testing and scrutiny. By combining the speed and efficiency of intuition with the rigor and objectivity of analysis, we can arrive at more robust and reliable decisions and solutions.

This kind of holistic approach to problem solving is particularly valuable in domains where there are many complex, interrelated factors to consider, such as in strategic planning, policy making, or scientific research. By leveraging both intuitive and rational modes of thinking, we can generate more creative and effective solutions, while also ensuring that they are grounded in evidence and logic.

Strategies for Cultivating and Refining Intuition

Given the potential benefits of intuition, it is worth considering strategies for cultivating and refining our intuitive capabilities, while also mitigating the risks of bias and error.

One key strategy is to actively seek out diverse experiences and perspectives, in order to broaden our knowledge base and expand our repertoire of unconscious associations and patterns. By exposing ourselves to new and challenging situations, we can develop a more flexible and adaptive intuitive sense, while also reducing the risk of becoming overly reliant on narrow or biased heuristics.

Another strategy is to practice mindfulness and self-reflection, in order to become more aware of our own thought processes and biases. By regularly examining our assumptions and mental models, we can identify potential blind spots or areas for improvement, and develop a more nuanced and accurate intuitive sense.

Finally, it can be valuable to cultivate a “beginner’s mind” or a stance of openness and curiosity, even in domains where we have significant expertise or experience. By approaching each situation with fresh eyes and a willingness to question our own assumptions, we can maintain a more flexible and adaptive intuitive sense, while also reducing the risk of becoming overly rigid or dogmatic in our thinking.

Synchronicity?

Carl Jung and Wolfgang Pauli: A Detailed Look at Their Correspondence

The correspondence between Carl Jung and Wolfgang Pauli, which lasted from 1932 to 1958, was a rich and dynamic exchange of ideas that shaped both men’s thinking and had a profound impact on their respective fields.

One of the central themes of their correspondence was the concept of synchronicity, which Jung first introduced in the early 1930s. Synchronicity refers to the meaningful coincidence of two or more events that are not causally related, but which seem to have a significant connection. Jung believed that synchronicity was evidence of an underlying unity between the physical world and the psychological realm, and that it could provide insights into the nature of reality and the workings of the unconscious mind.

Pauli was deeply intrigued by the concept of synchronicity and saw it as a potential bridge between quantum physics and psychology. In their correspondence, Pauli and Jung explored the implications of synchronicity for our understanding of causality, time, and the relationship between mind and matter.

Over the course of their exchanges, the concept of synchronicity evolved and took on new dimensions. Pauli helped Jung refine his ideas and provided insights from the world of physics that enriched Jung’s understanding of the phenomenon. For example, Pauli introduced Jung to the concept of “nonlocality” in quantum mechanics, which refers to the ability of particles to influence each other instantaneously across vast distances. This idea resonated with Jung’s notion of synchronicity and suggested that there may be a deeper level of reality that transcends the boundaries of space and time.

Another key aspect of their correspondence was the exploration of the relationship between the conscious and unconscious mind. Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, which posits the existence of a shared, inherited reservoir of symbols and archetypes, was of particular interest to Pauli. He saw parallels between the collective unconscious and the abstract mathematical structures that underlie the physical world, and believed that there may be a fundamental connection between the two.

Pauli also introduced Jung to the concept of “complementarity” in quantum mechanics, which holds that two seemingly contradictory descriptions of a phenomenon can both be true and necessary for a complete understanding. Jung saw this as analogous to the relationship between the conscious and unconscious mind, and believed that both were essential aspects of the psyche that needed to be integrated for wholeness and psychological health.

The influence of Albert Einstein on Jung’s thinking is evident throughout his correspondence with Pauli. Jung was deeply impressed by Einstein’s theory of relativity and saw it as a revolutionary breakthrough that challenged traditional notions of space, time, and causality. He believed that the theory of relativity had profound implications for psychology and that it could provide a framework for understanding the subjective nature of human experience.

In his writings, Jung often used the theory of relativity as a metaphor for the psychological relativity of the unconscious mind. Just as the perception of time and space is dependent on the observer’s frame of reference in physics, Jung believed that the contents of the unconscious are shaped by an individual’s unique history, culture, and personal experiences.

Einstein’s influence can also be seen in Jung’s conception of the “psychoid” nature of the archetypes. Jung believed that the archetypes were not purely psychological, but had a quasi-physical aspect that could manifest in the material world. This idea was inspired, in part, by Einstein’s notion of the “field” in physics, which suggests that seemingly empty space is actually filled with invisible forces and energies.

Throughout their correspondence, Jung and Pauli grappled with the implications of these ideas for the nature of reality and the relationship between mind and matter. They believed that the insights of depth psychology and quantum physics pointed towards a new understanding of the universe, one that recognized the fundamental interconnectedness of all things and the participatory role of consciousness in shaping reality.

These ideas continue to influence contemporary research in fields such as quantum cognition, psychophysics, and the study of consciousness. The legacy of Jung and Pauli’s collaboration is a testament to the value of interdisciplinary dialogue and the potential for science and spirituality to enrich and inform each other.

Their exploration of concepts such as synchronicity, the collective unconscious, and the complementarity of the psyche, as well as their engagement with the ideas of Albert Einstein and other leading thinkers of their time, continues to inspire and challenge researchers and scholars across a wide range of fields.

As we continue to grapple with the mysteries of the universe and the nature of human consciousness, the work of Jung and Pauli serves as a reminder of the importance of crossing disciplinary boundaries and remaining open to new and unconventional ways of thinking. By embracing the spirit of curiosity, collaboration, and intellectual humility that characterized their relationship, we may yet uncover new insights into the fundamental nature of reality and our place within it.

The Post-Secular Sacred Perspective