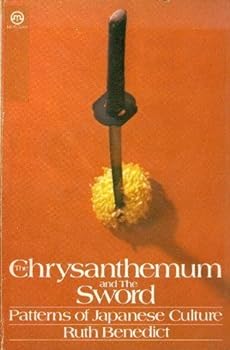

“The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” by Ruth Benedict, a landmark in cultural psychology, provides deep insights into the dynamics of guilt and shame within different cultures. Commissioned covertly as an exercise in weaponized anthropology by the OSS, now called the CIA, this book was originally intended to help Americans understand Japanese culture for post-war business and diplomatic relations. It offers an unparalleled window into how societies process trauma and how these mechanisms shape cultural identities.

“The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” by Ruth Benedict, a landmark in cultural psychology, provides deep insights into the dynamics of guilt and shame within different cultures. Commissioned covertly as an exercise in weaponized anthropology by the OSS, now called the CIA, this book was originally intended to help Americans understand Japanese culture for post-war business and diplomatic relations. It offers an unparalleled window into how societies process trauma and how these mechanisms shape cultural identities.

The Purpose of The Chrysanthemum and the Sword

Its purpose was to help American businesses understand how to do business with the newly capitalized Japanese. This was an attempt to stop the culture from reverting to back to an imperialist core and feudalistic policies of the state that could have created another war. In order for business partnerships to exist American business would have to learn to do business with a culture completely different from their own.

The role of Shinto Religion in Japanese Feudalism

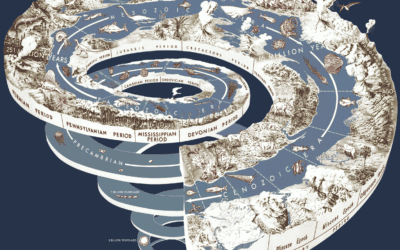

Prior to World War II, State Shinto was deeply embedded in Japanese national identity and governance. It was not just a religion but a state ideology that emphasized imperial worship and nationalism. This form of Shinto played a significant role in fostering the militarism and imperial expansion that led to Japan’s involvement in the war.

Disestablishment of State Shinto

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, the Allied occupation, led by the United States, initiated several reforms to dismantle the militaristic and imperial aspects of Japanese society. A key part of this process was the disestablishment of State Shinto. This involved removing Shinto’s influence from government and education, thereby separating religion from state affairs. The aim was to promote democratic values and prevent the resurgence of militaristic nationalism.

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, the Allied occupation, led by the United States, initiated several reforms to dismantle the militaristic and imperial aspects of Japanese society. A key part of this process was the disestablishment of State Shinto. This involved removing Shinto’s influence from government and education, thereby separating religion from state affairs. The aim was to promote democratic values and prevent the resurgence of militaristic nationalism.

“The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” and Cultural Understanding

Ruth Benedict’s “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” played a pivotal role in this transitional period. Commissioned to help Americans understand Japanese culture, the book provided insights into the fundamental values and social norms of Japan. It explored the dichotomy within Japanese culture – the aesthetic and pacifist qualities symbolized by the chrysanthemum, contrasted with the martial values represented by the sword.

Benedict’s work helped American policymakers and businessmen comprehend the complexities of Japanese society, including its religious and ethical systems. This understanding was crucial for the effective implementation of reforms and for establishing a foundation for future diplomatic and business relationships.

Prior to World War II, State Shinto was deeply embedded in Japanese national identity and governance. It was not just a religion but a state ideology that emphasized imperial worship and nationalism. This form of Shinto played a significant role in fostering the militarism and imperial expansion that led to Japan’s involvement in the war.

Disestablishment of State Shinto

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, the Allied occupation, led by the United States, initiated several reforms to dismantle the militaristic and imperial aspects of Japanese society. A key part of this process was the disestablishment of State Shinto. This involved removing Shinto’s influence from government and education, thereby separating religion from state affairs. The aim was to promote democratic values and prevent the resurgence of militaristic nationalism.

Ruth Benedict’s “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” played a pivotal role in this transitional period. Commissioned to help Americans understand Japanese culture, the book provided insights into the fundamental values and social norms of Japan. It explored the dichotomy within Japanese culture – the aesthetic and pacifist qualities symbolized by the chrysanthemum, contrasted with the martial values represented by the sword.

Benedict’s work helped American policymakers and businessmen comprehend the complexities of Japanese society, including its religious and ethical systems. This understanding was crucial for the effective implementation of reforms and for establishing a foundation for future diplomatic and business relationships.

Published in 1946, “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” was pivotal in shaping American perceptions of Japan after World War II. This book dissected the complex fabric of Japanese culture, highlighting the interplay between the aesthetic gentleness of the chrysanthemum and the disciplined harshness of the sword. Benedict’s analysis provided a framework for understanding Japanese social norms and business etiquette, crucial for Americans in the post-war era.

Japan and Godzilla

The 1954 film Godzilla serves as a profound cultural metaphor for Japan’s processing of trauma. It reflects the nation’s struggle with its imperialist past and the moral quandary of the double edged sword of becoming a nuclear power. The movie can be seen as Japan’s attempt to come to terms with the horrors of war and its aftermath, illustrating the complex relationship between cultural expression and historical events. Japan was devastated by nuclear weapons for many years after due to the effects of radiation. Japan remains one of the most opposed countries to the growth of nuclear weapons.

The 1954 film Godzilla serves as a profound cultural metaphor for Japan’s processing of trauma. It reflects the nation’s struggle with its imperialist past and the moral quandary of the double edged sword of becoming a nuclear power. The movie can be seen as Japan’s attempt to come to terms with the horrors of war and its aftermath, illustrating the complex relationship between cultural expression and historical events. Japan was devastated by nuclear weapons for many years after due to the effects of radiation. Japan remains one of the most opposed countries to the growth of nuclear weapons.

Beyond its nuclear symbolism, Godzilla also represents a reflection on Japan’s imperial history. During the early 20th century, Japan engaged in aggressive expansionism, leading to its involvement in World War II and eventual defeat. Godzilla can be interpreted as an allegory for this period of militaristic ambition, where the pursuit of power led to catastrophic consequences. The monster’s uncontrollable nature and the destruction it brings reflect the uncontrollable consequences of imperial overreach.

The recurring theme of Godzilla in Japanese cinema highlights the nation’s ongoing process of cultural reflection and trauma processing. Each iteration of Godzilla addresses different aspects of Japan’s history and current concerns, serving as a vessel for collective memory and introspection. The films offer a way for Japanese society to engage with and process its complex history, from the impact of war to the ethical dilemmas of technological advancement and modernization.

The Chrysanthemum: Symbol of Peace and Beauty

The chrysanthemum, revered in Japanese culture, symbolizes elegance, refinement, and the transient nature of life. It is associated with the Imperial family, often referred to as the Chrysanthemum Throne, signifying nobility and purity. In a broader cultural context, the chrysanthemum represents the more peaceful, aesthetic aspects of Japanese society. It embodies beauty, artistic expression, and the delicate balance of nature. This flower is also integral to various Japanese festivals and rituals, further solidifying its role as a symbol of harmony and tranquility. The celebration of the chrysanthemum in Japanese art and literature underscores the value placed on beauty, impermanence, and the cyclical nature of life.

The chrysanthemum, revered in Japanese culture, symbolizes elegance, refinement, and the transient nature of life. It is associated with the Imperial family, often referred to as the Chrysanthemum Throne, signifying nobility and purity. In a broader cultural context, the chrysanthemum represents the more peaceful, aesthetic aspects of Japanese society. It embodies beauty, artistic expression, and the delicate balance of nature. This flower is also integral to various Japanese festivals and rituals, further solidifying its role as a symbol of harmony and tranquility. The celebration of the chrysanthemum in Japanese art and literature underscores the value placed on beauty, impermanence, and the cyclical nature of life.

The Sword: Emblem of Honor and Strength

The sword, particularly the samurai sword or katana, is a potent symbol of Japanese history and ethics. It represents the martial virtues of bravery, honor, and loyalty. The sword is deeply connected to the samurai code, known as bushido, which emphasizes courage, honor, and personal sacrifice for the greater good. In “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword,” the sword symbolizes the disciplined, warrior aspect of Japanese culture. It stands for the capacity for order, the respect for hierarchical relationships, and the willingness to defend one’s honor and duty, even at the cost of one’s life. The sword also reflects the historical period of feudal Japan, where the samurai class played a pivotal role in shaping societal norms and values.

The sword, particularly the samurai sword or katana, is a potent symbol of Japanese history and ethics. It represents the martial virtues of bravery, honor, and loyalty. The sword is deeply connected to the samurai code, known as bushido, which emphasizes courage, honor, and personal sacrifice for the greater good. In “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword,” the sword symbolizes the disciplined, warrior aspect of Japanese culture. It stands for the capacity for order, the respect for hierarchical relationships, and the willingness to defend one’s honor and duty, even at the cost of one’s life. The sword also reflects the historical period of feudal Japan, where the samurai class played a pivotal role in shaping societal norms and values.

Dual Symbolism in Japanese Culture

Benedict’s choice of these two symbols – the chrysanthemum and the sword – captures the essence of Japanese culture, which harmonizes soft, aesthetic values with strong, disciplined virtues. This duality is a recurring theme in Japanese history and society, where grace and beauty coexist with strength and honor.

The interplay of these symbols reflects the complexities of Japanese identity, where societal harmony (represented by the chrysanthemum) is as prized as individual bravery and moral integrity (symbolized by the sword). This balance is evident in various aspects of Japanese life, from its art and literature to social customs and government policies.

The Dichotomy of Guilt and Shame Cultures

Benedict’s work highlights a significant cultural divide in how guilt and shame are perceived and managed in different societies. In the United States, influenced by Protestantism and Catholicism, guilt is an internalized emotion. Catholicism and Protestantism handle guilt differently but both emphasis private penance and confession of guilt and sin. Moral and ethical lapses are dealt with privately, leading to what Benedict describes as a ‘guilt culture.’ United States movie heroes often suffer with a traumatized past that they reconcile with privately and seek to atone for. This internalization often results in personal moral responsibility but can also cause isolation and internalized distress, impacting mental health.

In Japan, conversely, shame is a public and performative emotion. Japan’s ceremonial past meant that coming to terms with guilt and shame was a public event and social merit came from publicly atoning for wrong doing. In Japan harmony and adherence to societal norms are paramount, leading to a ‘shame culture.’ This approach encourages community cohesion and external regulation of behavior, but can also suppress individual expression and lead to social anxiety and low self-esteem.

Mental Health Implications

The differing approaches to guilt and shame in these cultures have significant mental health implications. In guilt cultures, the emphasis on personal conscience can foster autonomy and ethical behavior but can also lead to depression and anxiety due to internalized guilt. Shame cultures, while promoting social harmony, can cause individuals to suppress their emotions, potentially leading to issues like low self-esteem and social anxiety.

Understanding these cultural nuances was crucial for Western businesses entering Japan in the mid-20th century. “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” provided them with essential insights into Japanese social norms and business practices. This knowledge allowed Western businessmen to navigate Japanese corporate culture effectively, respecting its hierarchical structure and collective decision-making processes.

Conclusion

“The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” remains a vital resource in understanding the intricate ways in which societies process guilt and shame. For psychotherapists and cultural analysts, this book offers invaluable insights into the impacts of these emotions on individual and societal levels. By exploring the cultural dimensions of guilt and shame, we can better understand and navigate the complex landscape of international relations and mental health.

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/

Bibliography:

Benedict, R. (1946). The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture. Houghton Mifflin. This landmark work in cultural anthropology, commissioned by the U.S. government during World War II, provides deep insights into the cultural dynamics of Japan, particularly the interplay between the aesthetics and martial values symbolized by the chrysanthemum and the sword. Benedict’s analysis of the role of shame and guilt in Japanese society has had a lasting impact on our understanding of cross-cultural differences in psychological and social norms.

Godzilla. (1954). Directed by Ishirō Honda. The iconic Japanese film Godzilla serves as a profound cultural metaphor for Japan’s processing of the trauma of World War II and the moral quandary of becoming a nuclear power. The film reflects the nation’s struggle with its imperialist past and the complex relationship between cultural expression and historical events. Godzilla has been the subject of extensive analysis by scholars exploring the intersection of Japanese identity, collective memory, and the ethical dilemmas of technological advancement.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books. Yalom, a influential figure in modern psychotherapy, has acknowledged the impact of Moreno’s ideas on his own existential approach. Yalom’s work emphasizes the therapist-client relationship as a journey of mutual discovery and growth, resonating with Moreno’s philosophy of the therapeutic process being a shared experience of healing and insight.

Yalom, I. D. (2002). The Gift of Therapy: An Open Letter to a New Generation of Therapists and Their Patients. HarperCollins. In this seminal work, Yalom shares his reflections on the art and craft of psychotherapy, drawing inspiration from his predecessors like Moreno. Yalom’s emphasis on the therapist’s openness, empathy, and willingness to learn from clients aligns with Moreno’s model of the therapist as a collaborative partner in the therapeutic journey.

Moreno, J. L. (1946). Psychodrama (Vol. 1). Beacon House. Moreno’s groundbreaking work on psychodrama, a therapeutic method that uses spontaneous dramatization and role-playing, was a revolutionary departure from traditional psychoanalytic techniques. Psychodrama’s focus on action, interaction, and the exploration of interpersonal dynamics has had a lasting influence on the field of group therapy and experiential approaches to mental health.

Moreno, J. L. (1953). Who Shall Survive? Foundations of Sociometry, Group Psychotherapy and Sociodrama (2nd ed.). Beacon House. In this seminal work, Moreno lays the foundations for his theories of sociometry, group psychotherapy, and sociodrama. His innovative approaches to understanding and working with group dynamics have been widely adopted in various therapeutic modalities, including family therapy and organizational development.

Kellermann, P. F. (1992). Focus on Psychodrama: The Therapeutic Aspects of Psychodrama. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. Kellermann’s comprehensive exploration of the therapeutic aspects of psychodrama provides a deep dive into Moreno’s methods and their practical applications in clinical settings. This work delves into the key components of psychodrama, such as role reversal, the use of props, and the role of the director-therapist, offering a thorough understanding of Moreno’s pioneering approach.

Further Reading:

Blatner, A. (1996). Acting-In: Practical Applications of Psychodramatic Methods (3rd ed.). Springer Publishing Company. This book offers a practical guide to incorporating psychodramatic techniques into various therapeutic settings, highlighting the versatility and efficacy of Moreno’s methods. Blatner’s work provides a comprehensive overview of the theoretical foundations and practical applications of psychodrama, sociodrama, and related experiential approaches.

Blatner, A., & Blatner, A. (1988). Foundations of Psychodrama: History, Theory, and Practice (4th ed.). Springer Publishing Company. This seminal text delves into the historical development, theoretical underpinnings, and practical implementation of psychodrama, sociodrama, and related experiential therapies. Blatner’s extensive exploration of Moreno’s work and its evolution over time offers a deep understanding of the philosophical and practical significance of this approach.

Corsini, R. J. (1995). Role Playing in Psychotherapy. Routledge. Corsini’s work examines the role of role-playing and enactment in various therapeutic modalities, including psychodrama. This book provides a comprehensive analysis of the theoretical and practical aspects of using role-playing as a tool for personal growth, conflict resolution, and emotional exploration.

Dayton, T. (2005). The Living Stage: A Step-by-Step Guide to Psychodrama, Sociometry, and Experiential Group Therapy. Health Communications, Inc. Dayton’s practical guide offers a detailed overview of the psychodramatic method, including step-by-step instructions for facilitating psychodrama sessions. This resource serves as a valuable tool for therapists and practitioners seeking to incorporate Moreno’s techniques into their clinical work.

Schützenberger, A. A. (1998). The Ancestor Syndrome: Transgenerational Psychotherapy and the Hidden Links in the Family Tree. Routledge. Schützenberger’s work explores the concept of transgenerational trauma and the impact of ancestral experiences on individual and family dynamics. This book highlights the relevance of Moreno’s sociometric approach in understanding and addressing intergenerational patterns and their influence on personal growth and healing.

Lebra, T. S. (1976). Japanese Patterns of Behavior. University of Hawaii Press. Lebra’s comprehensive study of Japanese cultural norms, social structures, and interpersonal dynamics provides a deeper understanding of the context in which Benedict’s “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” was written. This work offers valuable insights into the nuances of Japanese society and the cultural factors that shape individual and collective behavior.

Doi, T. (1981). The Anatomy of Dependence. Kodansha International. Doi’s seminal work on the cultural concept of “amae” in Japan, which refers to a unique form of dependent behavior, offers a nuanced perspective on the psychological and social dynamics within Japanese society. This understanding is crucial in interpreting the cultural implications of Benedict’s analysis and the challenges faced by Western businesses and policymakers in navigating Japanese norms.

Wiessner, S. (2015). The Cultural Dynamics of Shellshock: The Godzilla Phenomenon in Post-War Japan. Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema, 9(2), 134-152. This scholarly article delves into the cultural symbolism and psychological underpinnings of the Godzilla franchise, exploring how the iconic monster serves as a vessel for Japan’s collective processing of the traumas of war and the ethical dilemmas of technological advancement. The analysis sheds light on the complex relationship between cultural expression and historical events in the Japanese context.

0 Comments