Back in the 1970s, the founders of NLP claimed they’d discovered something remarkable: that you could tell what someone was thinking by watching where their eyes moved. Look up and to the right? Creating a visual image. Down and to the left? Accessing feelings. It was elegant, seductive, and as it turned out, completely unsupported by research.

But here’s where things get interesting. While the idea of reading thoughts through eye movements fell apart under scientific scrutiny, something else emerged. Therapists noticed that guiding people’s eyes through specific movements while they recalled difficult memories seemed to help. Not in the way NLP predicted, but help nonetheless.

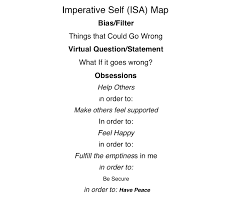

The Imperative Self-Analysis map represents one attempt to salvage something useful from the wreckage of NLP’s eye accessing cues. Instead of claiming to decode inner experience by watching where someone naturally looks, the IS map provides a framework for deliberately moving the eyes to facilitate therapeutic change. It’s the difference between claiming you can read someone’s mind by their eye movements and using eye movements as an intervention tool.

From Chaos to Structure

The original NLP model had a fundamental problem: it wasn’t reproducible. Different trainers taught different patterns. Some said up-right was visual constructed, others said it was visual remembered for left-handed people. The whole system was a mess of contradictions and special cases.

The IS map attempts to solve this by creating a standardized grid. Think of it like moving from everyone having their own personal map of a city to finally agreeing on north being up. The map typically organizes the visual field into zones, with practitioners guiding clients to move their eyes to specific positions while holding traumatic or problematic material in awareness.

Upper positions get associated with imagery and future thinking. Middle positions with present awareness. Lower positions with body sensations and past experiences. But here’s the crucial difference from NLP: these aren’t claimed as hardwired brain facts. They’re organizational tools, scaffolding for the intervention rather than neurological truth claims.

EMI Versus EMDR: Two Roads Diverged

Eye Movement Integration grew directly from attempts to systematize NLP patterns. Developed by Connirae and Steve Andreas, EMI involves smooth, continuous eye movements across multiple directions. You might trace figure-eights, diagonal lines, or circles while maintaining focus on traumatic material. The idea is to access and integrate different aspects of the traumatic memory by engaging different neural networks.

EMDR took a different path. Francine Shapiro famously discovered the technique while walking in a park, noticing that disturbing thoughts lost their charge when her eyes moved rapidly back and forth. She developed this observation into a structured eight-phase protocol focusing primarily on horizontal bilateral movements.

The key difference isn’t just in the movements themselves but in what happened next. EMDR accumulated decades of controlled trials, meta-analyses, and neuroimaging studies. EMI remained largely in the realm of clinical practice without the same rigorous testing. One became an empirically supported treatment; the other remained an interesting possibility.

The Memory Reconsolidation Revolution

Here’s where modern neuroscience offers a potential explanation for why any of this works. When you retrieve a memory, it doesn’t just play back like a video. The memory temporarily destabilizes, becoming changeable before reconsolidating back into long-term storage. This window of plasticity, lasting perhaps a few hours, allows for the emotional charge or meaning of the memory to be updated.

Think of it like opening a Word document. While the file is open, you can edit it. When you save and close it, those changes become permanent. Memory reconsolidation works similarly. The act of retrieving a traumatic memory while simultaneously experiencing something incompatible with the original encoding (safety, bilateral stimulation, dual awareness) may allow the memory to reconsolidate with less emotional intensity.

Eye movements might facilitate this process in several ways. They tax working memory, making it harder to hold the traumatic image in full vividness. They activate bilateral brain networks, potentially facilitating integration. They create a mismatch between what the nervous system expects (danger) and what’s actually happening (sitting safely in a therapist’s office moving your eyes).

What Actually Works

The research tells us that bilateral stimulation, particularly eye movements, can reduce the vividness and emotionality of traumatic memories. This finding replicates across multiple laboratories and populations. What’s less clear is whether the specific patterns matter. Does a figure-eight work better than simple horizontal movements? Does accessing different eye positions engage different aspects of memory? These questions remain largely unanswered.

The IS map and similar frameworks might work not because they accurately map internal neurology but because they provide structure and intentionality to the intervention. They give both therapist and client a sense of systematic progress, of covering all the bases. This isn’t nothing. The therapeutic relationship and the sense of working through something methodically both contribute to healing.

The Pragmatic Middle Path

The Pragmatic Middle Path

So where does this leave us? We have theoretical frameworks built on discredited foundations that nonetheless seem to help some people. We have varying levels of evidence for different approaches. And we have clients who need help now, not after another decade of research.

The pragmatic approach acknowledges both what we know and what we don’t. EMDR has strong empirical support and should probably be the first choice for trauma work involving eye movements. But for clients who don’t respond to standard EMDR, or for clinicians trained in other approaches, frameworks like the IS map offer structured alternatives.

The key is transparency. Clients deserve to know what’s established science and what’s innovative practice. They should understand that while memory reconsolidation is real neuroscience, the specific zones of the IS map are organizational tools rather than brain facts. This isn’t deception; it’s informed consent.

Looking Forward

The evolution from NLP’s eye accessing cues to structured interventions like the IS map shows how ideas transform in the crucible of clinical practice. What started as an oversimplified claim about reading minds through eye movements has evolved into sophisticated protocols for facilitating therapeutic change.

The next generation of research will likely focus on identifying the active ingredients in these interventions. Is it the eye movements themselves? The bilateral stimulation? The dual awareness? The memory reconsolidation? Or some combination of factors we haven’t yet identified? Advanced neuroimaging and carefully designed component studies will eventually provide answers.

Until then, clinicians will continue doing what they’ve always done: using the best available tools while remaining open to innovation. The IS map represents one such tool, born from questionable origins but potentially useful nonetheless. Not because it reveals hidden truths about how the brain organizes information, but because it provides a systematic way to engage therapeutic processes we’re only beginning to understand.

The real lesson might be that even flawed theories can lead to useful practices, as long as we’re willing to let go of the theory when evidence contradicts it while keeping what actually helps people heal.

0 Comments