The Philosophy That Listens to Bodies

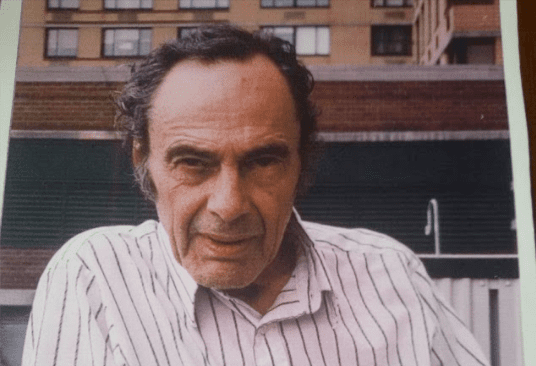

Eugene Gendlin occupies a curious position in the landscape of contemporary psychotherapy. Neither fully claimed by philosophers nor completely embraced by mainstream psychology, his work bridges territories that most thinkers are content to leave separate. Yet for those who understand trauma as fundamentally embodied, and for those who recognize that political oppression lives in bodies as much as in institutions, Gendlin offers something revolutionary: a precise philosophical framework for how organisms carry meaning forward through time, and how that carrying forward can become blocked, distorted, or liberated.

Gendlin studied under Carl Rogers and worked closely with him at the University of Chicago, but he noticed something troubling in the research data. Successful therapy clients did something different from unsuccessful ones, something that happened in the first two sessions and predicted outcome better than any therapeutic technique or theoretical orientation. The successful clients had a particular way of speaking that included pauses, uncertainty, and checking inside themselves for words that hadn’t yet formed. They were consulting something more than thoughts or emotions, something Gendlin would eventually call the “felt sense.”

This observation led Gendlin to develop both a philosophical framework (the Process Model) and a practical method (Focusing) that would revolutionize how we understand the relationship between body, meaning, and change. For trauma therapists, his work provides a map of how trauma disrupts the natural flow of experiencing and how that flow can be restored. For those interested in political liberation, Gendlin offers an understanding of how oppressive structures literally shape what can and cannot be felt, and therefore what can and cannot be thought or imagined.

The Felt Sense: Where Trauma Lives and Heals

The felt sense isn’t emotion, though emotion may be part of it. It isn’t body sensation, though sensation may be part of it. It isn’t thought, though thought may emerge from it. The felt sense is the unclear, murky, not-yet-articulated sense of a whole situation that forms in the body when we pause and attend inwardly. It’s the “something” that knows more than we can explicitly say, the bodily knowledge that encompasses the complexity of lived experience before it gets parceled out into the categories of thought, feeling, and sensation.

For trauma survivors, the felt sense often remains frozen or fragmented. Trauma disrupts what Gendlin calls “carrying forward,” the natural process by which experience moves through time, creating fresh meaning and new possibilities. Instead of carrying forward, traumatic experience becomes stuck in repetition. The body continues to live in the traumatic moment, unable to sequence into fresh experiencing. This isn’t merely psychological but profoundly somatic: the organism’s basic process of implying and occurring has been disrupted.

Gendlin’s concept of “implying” is crucial here. Every moment of living implies a next step, a forward movement into the future. The lungs imply the next breath, hunger implies eating, a question implies searching for an answer. But trauma disrupts this implying. The traumatized body implies danger even in safety, implies abandonment even in connection, implies powerlessness even when agency is possible. The felt sense becomes frozen around the traumatic disruption, unable to imply anything beyond repetition of the original wound.

Traditional talk therapy often fails with trauma because it addresses only the cognitive level, leaving the felt sense untouched. A survivor can understand perfectly well that they’re now safe, that the trauma is over, that their reactions are symptoms of PTSD, and still remain trapped in the bodily patterns of traumatic response. The felt sense hasn’t shifted because understanding alone doesn’t create carrying forward. Something more is needed, something that engages the body’s own wisdom about how to resume its interrupted flow.

Focusing: The Practice of Precision

Gendlin’s Focusing offers a precise method for engaging the felt sense and facilitating carrying forward. Unlike cathartic approaches that seek to discharge trapped energy, or cognitive approaches that aim to restructure thoughts, Focusing works with the edge between the formed and unformed, the place where new meaning can emerge from the body’s own intelligence. This edge is delicate, requiring a particular quality of attention that neither forces nor abandons the process.

The Focusing process invites a gentle, curious attention to the unclear felt sense of a situation or problem. Rather than trying to analyze or fix, the focuser simply keeps company with what’s there, describing it in tentative words or images and checking these against the bodily feeling to see if they resonate. When the right words or images are found, the body responds with what Gendlin calls a “felt shift,” a physical easing that signals carrying forward has resumed. It’s not that the problem is solved but that the organism’s natural process of creating fresh meaning has been restored.

For trauma work, this is revolutionary. Instead of requiring survivors to directly confront traumatic memories, which can retraumatize, or to endlessly analyze their patterns, which can reinforce disconnection from the body, Focusing allows a gentle approach to the edges of traumatic experience. The focuser might sit with the felt sense of “something about safety” or “that whole thing with trust” without needing to explicitly revisit traumatic events. The body knows what needs attention and will reveal it at a pace that doesn’t overwhelm the system.

This approach recognizes that healing from trauma isn’t about getting rid of symptoms but about restoring the organism’s capacity for fresh experiencing. When carrying forward resumes, symptoms often resolve naturally because they were simply the body’s way of signaling that something was stuck. The hypervigilance relaxes when the body can again imply safety. The dissociation resolves when the body can again imply presence. The numbness thaws when the body can again imply feeling.

The Political Body: How Oppression Stops Carrying Forward

Gendlin’s work has profound political implications that extend far beyond individual therapy. If experiencing happens through bodily felt sensing, and if felt sensing can be disrupted or facilitated by environmental conditions, then political structures that systematically disrupt felt sensing are engaged in a form of violence that goes deeper than physical coercion or ideological manipulation. They’re disrupting the very process through which humans create meaning and navigate their worlds.

Consider how oppressive systems work. They don’t just limit external freedoms but shape what can be felt and therefore what can be thought. A person raised under authoritarian conditions doesn’t just learn to comply externally while maintaining inner freedom. Their very capacity for felt sensing becomes shaped by the need to not feel certain things, to not let certain implications form, to not allow certain kinds of carrying forward. The body learns to stop itself before dangerous feelings or thoughts can even begin to form.

This is what Gendlin calls “stopped processes,” experiences that begin to form but are interrupted before they can carry forward into meaning. In oppressive contexts, certain feelings, thoughts, and possibilities must remain stopped to ensure survival. The body learns to not even begin to imply certain directions. A woman in a deeply patriarchal context doesn’t just learn to not speak certain thoughts; her body learns to not let those thoughts form in the first place. The felt sense that might lead to questioning or resistance never fully develops.

This bodily shaping of possibility happens along every axis of oppression. Racism doesn’t just limit opportunities; it shapes what bodies can feel and therefore what futures can be implied. Class oppression doesn’t just restrict resources; it conditions what aspirations can even begin to form in the felt sense. Heteronormativity doesn’t just punish certain expressions; it prevents certain feelings from ever developing enough to require expression.

Therapeutic Activism: Creating Conditions for Carrying Forward

Understanding oppression as the systematic disruption of carrying forward transforms how we think about both therapy and political action. Individual healing cannot be separated from collective liberation because the same structures that traumatize individuals also prevent the collective body from carrying forward into new possibilities. Therapy that ignores political context risks trying to restore carrying forward in individuals while leaving in place the very structures that disrupted it.

This doesn’t mean turning therapy sessions into political education, but rather recognizing that creating conditions for carrying forward is inherently political. When a therapist creates a space where a client can feel what they’ve never been allowed to feel, think what they’ve never been allowed to think, and imply what they’ve never been allowed to imply, they’re engaging in a radical act. They’re not just healing individual trauma but creating pockets of resistance to systems that depend on stopped processes.

Gendlin’s concept of “crossing” is particularly relevant here. Crossing happens when different contexts or experiences that are usually kept separate are allowed to interact, creating new meaning that couldn’t exist in either alone. In therapy, when someone brings their political understanding into contact with their personal pain, or their spiritual experience into contact with their sexuality, crossing creates new possibilities for carrying forward. The boundaries that oppression depends on begin to dissolve.

This is why somatic approaches to trauma are so powerful for survivors of political violence, racism, and other forms of systemic oppression. These approaches don’t just help people think differently about their experiences but actually restore the bodily capacity for fresh experiencing that oppression disrupted. They create conditions where stopped processes can resume, where the body can again imply futures that oppression had foreclosed.

The Focusing Partnership: Mutual Liberation

One of Gendlin’s most radical innovations was the development of Focusing partnerships, where two people take turns Focusing while the other serves as a compassionate witness. This isn’t therapy in the traditional sense but a practice of mutual support that recognizes both people as capable of accessing their own bodily wisdom. The partnership model disrupts the power dynamics inherent in traditional therapy while maintaining the value of supportive presence.

For communities dealing with collective trauma and systemic oppression, the partnership model offers a way to heal that doesn’t depend on access to professional services or require people to position themselves as patients. It recognizes that the capacity for healing exists within communities themselves, needing only the right conditions to flourish. When members of oppressed communities Focus together, they’re not just healing individual wounds but creating collective spaces where stopped processes can resume.

The political implications are profound. If oppression works by disrupting carrying forward, then creating spaces where carrying forward can resume is a form of resistance. Focusing partnerships become sites of liberation where people can feel what the dominant culture says they shouldn’t feel, know what they’re not supposed to know, and imagine what they’re not supposed to imagine. The body’s wisdom, which oppression sought to silence, begins to speak again.

The Political Body: How Abstraction Divorces Us from Wisdom

Gendlin’s work illuminates a critical problem in contemporary political discourse: we’ve become trapped in abstract logical arguments that have lost connection with embodied knowing. Political debates increasingly occur at the level of pure reasoning, ideological frameworks, and theoretical constructs, while the felt sense of actual lived experience gets dismissed as mere emotion or bias. This disconnection between top-down logical processing and bottom-up embodied wisdom creates the polarization and paralysis that characterizes modern politics.

Consider how political arguments typically unfold. People marshal facts, construct logical chains, cite authorities, and build elaborate theoretical frameworks, yet rarely change anyone’s mind. This isn’t because humans are inherently irrational but because political convictions don’t actually form through logic alone. They emerge from the felt sense of lived experience, from the body’s accumulated knowing about safety and threat, belonging and exclusion, possibility and limitation. When political discourse operates only at the level of abstract reasoning, it fails to engage the felt sense where actual change happens.

Gendlin’s philosophy suggests that our current political dysfunction stems from over-relying on what he calls “unit model thinking,” where we manipulate fixed concepts and categories rather than attending to the fluid, implicit intricacy of actual situations. Political ideologies, whether left or right, become rigid conceptual systems that prevent fresh thinking. People become more committed to logical consistency within their chosen framework than to accurate perception of complex reality. The felt sense, which could provide corrective feedback about what’s actually happening, gets overridden by the need to maintain ideological coherence.

This creates what Gendlin would recognize as stopped processes at a collective level. When political thinking becomes purely abstract, the natural carrying forward of collective wisdom stops. Instead of policies emerging from careful attention to what communities actually experience and need, we get top-down solutions based on theoretical models. Instead of dialogue that allows different perspectives to cross and create new understanding, we get parallel monologues where each side simply reinforces its existing framework.

Philosophical Roots: From Dilthey to Phenomenology

Gendlin’s thinking emerged from deep engagement with the Continental philosophical tradition, particularly Wilhelm Dilthey’s Lebensphilosophie and the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. From Dilthey, Gendlin inherited the conviction that life cannot be fully captured in concepts, that lived experience always exceeds what can be explicitly articulated. Dilthey’s notion of Verstehen (understanding) as something different from scientific explanation profoundly influenced Gendlin’s approach to meaning-making.

Husserl’s phenomenology provided Gendlin with rigorous methods for attending to experience as it actually occurs, before it gets categorized and conceptualized. But where Husserl sought pure essences, Gendlin found process and interaction. The felt sense isn’t a thing to be described but an ongoing interaction between organism and environment that generates meaning. This shift from static phenomenology to process philosophy marks one of Gendlin’s major contributions.

From Heidegger, Gendlin learned about the importance of implicit understanding, the background sense of Being that underlies explicit knowledge. But Gendlin went beyond Heidegger’s often abstract formulations to develop precise practices for accessing and working with implicit knowing. Where Heidegger wrote about dwelling and clearing, Gendlin created Focusing, a concrete method anyone can learn.

The influence of American pragmatism, particularly John Dewey and William James, also shaped Gendlin’s thinking. From Dewey, he took the understanding that thinking emerges from and returns to experience, that concepts are tools for navigating situations rather than representations of fixed reality. From James, he inherited appreciation for the “fringe” of consciousness, the vague sense of tendency and direction that guides thinking before it becomes explicit.

Beyond Logic: The Intelligence of Feeling-Thinking

What Gendlin offers politically isn’t an abandonment of logic but a recognition that effective reasoning must stay connected to felt experiencing. The problem isn’t that people think too much but that their thinking has become disconnected from the embodied wisdom that could guide it toward productive solutions. When logic operates in isolation from felt sense, it becomes what Gendlin calls “empty concepts,” manipulations of symbols that have lost touch with what they supposedly represent.

Real political wisdom emerges from what Gendlin calls “thinking at the edge,” where clear concepts meet unclear but sensed experience. This isn’t anti-intellectual but represents a more sophisticated understanding of how human intelligence actually works. The greatest political thinkers have always operated this way, testing their theories against the felt sense of actual situations, allowing their frameworks to be modified by encounter with complexity that exceeds their categories.

When political discourse reconnects with felt sensing, several things become possible. First, people can recognize when their ideological positions don’t actually match their lived experience, creating openings for genuine reconsideration. Second, different perspectives can engage at a level deeper than conceptual argument, finding shared felt senses even when explicit positions differ. Third, novel solutions can emerge from the intersection of logical analysis and embodied wisdom, solutions neither purely rational nor purely intuitive but arising from their interaction.

This approach offers hope for transcending political polarization not through better arguments or more facts but through practices that reconnect abstract positions with embodied experience. When people learn to check their political opinions against their felt sense, to notice when logical positions create bodily discomfort or when embodied wisdom contradicts intellectual commitments, the rigid boundaries between political camps begin to soften. The goal isn’t to abandon principled positions but to ground them in the full intelligence of thinking-feeling organisms rather than in abstract logic alone.

0 Comments