Anna Freud’s Impact on Freud’s Biographical Scholarship

The systematic efforts to control and sanitize the historical record surrounding Freud have had profound and lasting consequences for our understanding of psychoanalysis and its founder. The work of Frederick Crews and other critical scholars has revealed the extent to which protective narratives, institutional interests, and family loyalty combined to create and maintain a fundamentally false picture of Freud’s life and work.

The case serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of maintaining critical approaches to biographical scholarship and ensuring open access to historical materials. It demonstrates how the control of information can distort our understanding of important figures and movements, creating myths that persist long after the original motivations for their creation have been forgotten.

The ongoing reassessment of Freud’s legacy illustrates both the resilience of scholarly inquiry and the challenges faced by researchers who attempt to challenge established narratives. It also highlights the responsibility of scholars to pursue truth even when it contradicts comfortable assumptions and threatens established interests.

The ultimate lesson may be that historical truth, however complex or uncomfortable, provides a more solid foundation for understanding than carefully constructed myths. The continued evolution of Freud scholarship demonstrates that the process of historical inquiry is never complete and that each generation must be prepared to reconsider the assumptions and narratives inherited from their predecessors.

The revelations about Freud’s life and work have implications that extend far beyond the historical record to touch on fundamental questions about the nature of scientific authority, the ethics of therapeutic practice, and the responsibility of intellectual communities to acknowledge uncomfortable truths about their foundational figures. As the full extent of the deceptions surrounding Freud’s legacy continues to emerge, scholars and practitioners alike must grapple with the challenge of building more honest and reliable foundations for their disciplines.

Frederick Crews’ comprehensive investigation in “Freud: The Making of an Illusion” presents a fundamental challenge to the traditional understanding of Sigmund Freud’s life and work. Drawing on rarely consulted archives and previously restricted materials, Crews has assembled extensive evidence revealing systematic efforts to control and sanitize the historical record surrounding psychoanalysis and its founder. This research has exposed how decades of selective access to materials and protective narratives have shaped even well-regarded biographical works, raising serious questions about the reliability of our understanding of psychoanalysis and its founder.

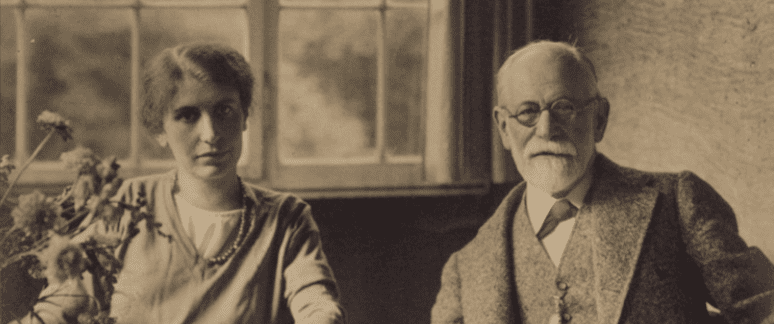

The Architecture of Control: Anna Freud’s Custodianship

Anna Freud’s role as guardian of her father’s legacy extended far beyond normal custodianship of family papers. As the controller of the Freud Archives and the primary gatekeeper to his correspondence, she wielded enormous influence over how scholars could access and interpret materials related to her father’s life and work. This position allowed her to shape the narrative that would emerge about Freud for decades to come.

The extent of materials under Anna Freud’s control was vast. Beyond the famous correspondence with Wilhelm Fliess, she had access to thousands of letters exchanged between Freud and his colleagues, patients, family members, and professional associates. These included correspondence with Carl Jung, Sandor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones, and many others who were central to the development of psychoanalysis. She also controlled access to patient records, case notes, drafts of published works, and personal diaries that could have provided crucial insights into Freud’s methods and thinking.

The Selective Release Strategy

The pattern of document release under Anna Freud’s oversight reveals a deliberate strategy of controlling information flow. Materials that supported the heroic narrative of Freud as a pioneering scientist and dedicated physician were made available to sympathetic scholars, while documents that might have raised uncomfortable questions about his methods, ethics, or claims were either withheld indefinitely or released only with significant restrictions.

This selective approach meant that even dedicated scholars working within the official channels of Freud studies were operating with an incomplete and potentially misleading picture of their subject. The materials they could access had been pre-filtered to support particular interpretations while suppressing others, creating a systematic bias in the scholarly literature that persisted for decades.

The Case of the Missing Correspondence

Freud was indeed a meticulous correspondent who maintained extensive written communication with colleagues, patients, and associates throughout his career. The survival of thousands of letters testifies to his careful preservation of materials and his recognition of their historical importance. This makes the absence of certain key documents all the more significant and suspicious.

The missing materials are not random losses but appear to follow patterns that suggest deliberate selection. Documents that might have revealed uncomfortable truths about Freud’s therapeutic methods, his relationships with patients, or his willingness to manipulate evidence have disappeared or been heavily edited, while less sensitive materials survived intact. The affair with Minna Bernays, while significant, represents only one aspect of a broader pattern of suppression that affected many areas of Freud’s life and work.

The Fliess Correspondence: A Case Study in Suppression

The correspondence between Freud and Wilhelm Fliess provides perhaps the clearest example of systematic suppression of potentially damaging materials. These letters, written during the formative years of psychoanalysis, contained Freud’s most candid admissions about his methods, his doubts about his theories, and his struggles with clinical practice.

When portions of the Fliess correspondence were finally published, scholars immediately noticed obvious gaps and abrupt transitions that indicated extensive editing. Contemporary references to the letters revealed that the most compromising passages had been removed, including Freud’s admissions of therapeutic failures and his acknowledgment that some of his published case studies were significantly embellished or entirely fabricated.

The Fabrication of Clinical Success

One of the most damaging revelations to emerge from newly available documents concerns the extent to which Freud misrepresented his clinical work. Evidence suggests that many of his famous case studies were either complete fabrications or gross distortions of actual therapeutic encounters, transformed to support his theoretical claims regardless of the actual outcomes.

The case of Sergei Pankejeff, the “Wolf Man,” provides a particularly clear example of this deception. While Freud presented this as a triumph of psychoanalytic technique, documentary evidence reveals that Pankejeff never experienced the cure that Freud claimed. Instead, he remained severely disturbed throughout his life, requiring ongoing financial support from psychoanalytic organizations partly to maintain his silence about the actual course of his treatment.

Similarly, other famous cases appear to have been largely fictional or heavily embellished. The therapeutic breakthroughs that Freud described often never occurred, and the patients’ symptoms frequently persisted long after their supposed successful analyses. In some instances, Freud appears to have based his published case studies on his own self-analysis rather than on actual patient encounters, presenting his personal psychological insights as if they had emerged from his treatment of others.

The Impact on Biographical Scholarship

The systematic control of materials has had profound consequences for Freud scholarship, affecting even the most respected biographical works. Scholars who built their research on the available materials were unknowingly working with sources that had been deliberately filtered and potentially manipulated to support particular narratives.

Peter Gay’s “Freud: A Life for Our Time,” widely regarded as the definitive scholarly biography, exemplifies this problem. While Gay’s scholarship was rigorous within the constraints he faced, his work was necessarily limited by the materials available through official channels. He accepted at face value many claims about missing documents and destroyed materials, not recognizing the extent to which his access was being controlled and his interpretations influenced by the protective narrative that had been constructed around Freud’s legacy.

The result was a biographical work that, despite its scholarly apparatus and comprehensive appearance, effectively perpetuated the mythological version of Freud’s life while obscuring the systematic distortions that had shaped the available evidence. Other respected biographers followed Gay’s lead, building upon his work and accepting his interpretations without recognizing the fundamental flaws in the source base.

The Institutional Protection of Reputation

Beyond individual family members, entire institutions became invested in maintaining the protective narrative around Freud. The Freud Archives, various psychoanalytic societies, and academic departments built around Freudian theory all had interests in preserving the founder’s reputation and the theoretical framework that justified their existence.

This institutional investment created a self-reinforcing system where challenging the official narrative became professionally dangerous for scholars. Those who pursued uncomfortable lines of inquiry found themselves excluded from access to materials, marginalized within their professional communities, and unable to publish their findings in mainstream journals devoted to psychoanalytic studies.

Frederick Crews and the Documentary Revolution

Crews’ achievement in “Freud: The Making of an Illusion” was made possible by his access to materials that had been suppressed for decades and his willingness to pursue uncomfortable truths regardless of professional consequences. As the original generation of protectors died and institutional control loosened, previously sealed documents became available to researchers prepared to challenge established narratives.

The newly available materials included not only the complete set of 1,539 engagement letters between Freud and Martha Bernays, but also correspondence with colleagues that had been heavily edited in previous publications, patient records that contradicted published accounts, and institutional documents that revealed the extent of cover-up efforts.

Crews approached these materials with methodological rigor that had been lacking in earlier Freud scholarship. Rather than accepting protective narratives at face value, he subjected claims to independent verification, cross-referenced sources, and followed evidence wherever it led, regardless of its implications for established reputations.

The Erosion of Protective Barriers

The work of Crews and other critical scholars has contributed to a fundamental shift in how Freud is understood within the scholarly community. The heroic narrative that dominated much of the 20th century has given way to a more complex and often damaging portrait of a man whose methods were often unethical, whose claims were frequently fabricated, and whose therapeutic results were largely fictional.

This transformation has been possible only because the barriers that protected Freud’s reputation for so long have finally begun to erode. The death of the original protectors, changes in institutional policies, and the emergence of new archival materials have created opportunities for more honest scholarship that were previously unavailable.

Implications for Psychoanalytic Practice

The revelations about Freud’s methods and their systematic misrepresentation have implications that extend far beyond historical biography. If the foundational case studies of psychoanalysis were fabricated or grossly distorted, this calls into question the empirical basis for many psychoanalytic concepts and techniques still used in clinical practice.

The discovery that Freud’s therapeutic successes were largely fictional raises serious questions about the effectiveness of psychoanalytic treatment and the ethical responsibility of practitioners who continue to use methods based on fraudulent claims. The psychoanalytic community has been slow to grapple with these implications, often preferring to maintain traditional narratives rather than confront uncomfortable truths about their discipline’s origins.

The Broader Lessons for Intellectual History

The case of Freud scholarship illustrates broader challenges in intellectual history and the study of influential figures. The systematic protection of certain narratives, however well-intentioned, can significantly distort our understanding of important intellectual and cultural developments.

The Freud case demonstrates how institutional control over source materials can shape historical understanding for generations, creating false narratives that become embedded in scholarly literature and popular culture. It also shows how the protective efforts of families, institutions, and professional communities can work together to maintain myths that serve their interests while obscuring historical truth.

Contemporary Scholarly Reassessment

The field of Freud studies has undergone significant evolution as new materials have become available and scholars have developed more critical approaches to evaluating the historical record. There is growing recognition that many long-held assumptions about Freud’s life and work need to be reconsidered in light of emerging evidence.

This reassessment has been controversial within the psychoanalytic community, with some defending traditional narratives while others have embraced more critical approaches. The debate reflects broader questions about how scientific and intellectual communities should respond to challenges to their foundational figures and theories.

The resistance to acknowledging the full extent of the problems with Freud’s legacy demonstrates the continued power of institutional interests and professional investments in maintaining established narratives. However, the weight of evidence has made it increasingly difficult to sustain the heroic version of Freud’s life and work that dominated scholarship for most of the 20th century.

The Ongoing Challenge of Historical Truth

The emergence of new documentary evidence has fundamentally altered our understanding of Freud’s life and work, but many questions remain unanswered. The systematic suppression of materials means that some aspects of the historical record may never be fully recovered, while the discovery of new documents continues to challenge established interpretations.

Future research will likely focus on continued examination of newly available materials, reassessment of established biographical claims, and evaluation of the methodological approaches used in earlier scholarship. The goal will be to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of Freud’s life and work, one that acknowledges both his cultural influence and his significant limitations and deceptions.

Bibliography

Appignanesi, Lisa, and John Forrester. Freud’s Women. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Borch-Jacobsen, Mikkel. Remembering Anna O.: A Century of Mystification. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Borch-Jacobsen, Mikkel, and Sonu Shamdasani. The Freud Files: An Inquiry into the History of Psychoanalysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Crews, Frederick. Freud: The Making of an Illusion. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017.

Crews, Frederick. Unauthorized Freud: Doubters Confront a Legend. New York: Viking, 1998.

Crews, Frederick. The Memory Wars: Freud’s Legacy in Dispute. New York: New York Review Books, 1995.

Dolnick, Edward. Madness on the Couch: Blaming the Victim in the Heyday of Psychoanalysis. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Esterson, Allen. Seductive Mirage: An Exploration of the Work of Sigmund Freud. Chicago: Open Court, 1993.

Eysenck, Hans J. Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire. New York: Viking, 1985.

Forrester, John. Dispatches from the Freud Wars: Psychoanalysis and Its Passions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. New York: W. W. Norton, 1988.

Grünbaum, Adolf. The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Hale, Nathan G. The Rise and Crisis of Psychoanalysis in the United States: Freud and the Americans, 1917-1985. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Jones, Ernest. The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, 3 volumes. New York: Basic Books, 1953-1957.

Kerr, John. A Most Dangerous Method: The Story of Jung, Freud, and Sabina Spielrein. New York: Knopf, 1993.

Maciejewski, Franz. Seduced and Abandoned: The Minna Bernays Affair. London: Karnac Books, 2007.

Malcolm, Janet. In the Freud Archives. New York: Knopf, 1984.

Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff. The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1984.

Masson, Jeffrey Moussaieff, editor. The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887-1904. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

Molnar, Michael, editor. The Diary of Sigmund Freud, 1929-1939: A Record of the Final Decade. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1992.

Neu, Jerome, editor. The Cambridge Companion to Freud. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Powell, Russell A., and Nancy Boer. “Did Freud Mislead Patients to Confabulate Memories of Abuse?” Psychological Reports 75, no. 3 (1994): 1283-1298.

Ramas, Maria. “Freud’s Dora, Dora’s Hysteria.” Feminist Studies 6, no. 3 (1980): 472-510.

Rosen, Paul. Freud and His Followers. New York: Knopf, 1975.

Rosenbaum, Ron, and Richard Pollak. “The Sins of the Father.” Harper’s Magazine, November 1992.

Schatzman, Morton. Soul Murder: Persecution in the Family. New York: Random House, 1973.

Schimek, Jean G. “Fact and Fantasy in the Seduction Theory: A Historical Review.” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 35, no. 4 (1987): 937-965.

Shamdasani, Sonu. “Memories, Dreams, Omissions.” In Unauthorized Freud, edited by Frederick Crews, 187-219. New York: Viking, 1998.

Sulloway, Frank J. Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend. New York: Basic Books, 1979.

Swales, Peter J. “Freud, Minna Bernays, and the Conquest of Rome: New Light on the Origins of Psychoanalysis.” New American Review 1, no. 2/3 (1982): 1-23.

Swales, Peter J. “Freud, His Teacher, and the Birth of Psychoanalysis.” In Freud: Appraisals and Reappraisals, edited by Paul E. Stepansky, 3-82. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press, 1986.

Thornton, E. M. The Freudian Fallacy: An Alternative View of Freudian Theory. Garden City, NY: Dial Press, 1984.

Van Rillaer, Jacques. “The Therapeutic Efficacy of Freud’s Psychoanalysis.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3, no. 3 (1980): 315-316.

Webster, Richard. Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science, and Psychoanalysis. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

Wilcocks, Robert. Maelzel’s Chess Player: Sigmund Freud and the Rhetoric of Deceit. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1994.

Young-Bruehl, Elisabeth. Anna Freud: A Biography. New York: Summit Books, 1988.

Hashtags

0 Comments