Memory Reconsolidation: The Hidden Mechanism Behind Why Therapy Works

For over a century, neuroscientists believed that once memories consolidated into long-term storage, they became essentially permanent. Sure, you might forget details over time, and new learning could interfere with old memories, but the original memory trace itself was thought to be stable and unchangeable. This understanding shaped how we thought about everything from education to psychotherapy. If traumatic memories were permanent, the best therapy could do was help people cope with them or build competing positive associations.

Then, around the turn of the millennium, a series of experiments shattered this fundamental assumption. Memories, it turned out, could be fundamentally rewritten. Not just covered over or competed with, but actually changed at their core. This discovery would eventually explain why many psychotherapy techniques work and suggest new directions for treating everything from PTSD to addiction.

The Accidental Discovery

The story begins not with humans but with rats in a laboratory in Brooklyn. In 1968, researchers Donald Lewis, John Misanin, and colleague were studying memory in rats using a standard fear conditioning paradigm. They’d pair a tone with a foot shock until the rats froze in fear whenever they heard the tone. Standard stuff for a behavioral neuroscience lab.

But Lewis and his team did something unusual. After the fear memory had consolidated, they reminded the rats of the fear by playing the tone again. Immediately after this reminder, they gave the rats electroconvulsive shock, known to disrupt memory formation. Classical theory said this should have no effect since the memory was already consolidated. Instead, the rats acted as if they’d never learned to fear the tone at all.

This was bizarre. Electroconvulsive shock given without the reminder did nothing to the memory. The shock only erased the memory when given right after the memory was retrieved. It was as if retrieving the memory had temporarily returned it to a fragile state where it could be disrupted.

The finding was so at odds with established theory that it was largely ignored. Some researchers tried to replicate it and failed. Others dismissed it as an artifact. The idea that consolidated memories could become fragile again seemed too radical. The paper languished in relative obscurity for decades.

The Resurrection

Everything changed in 2000 when Karim Nader, a postdoc in Joseph LeDoux’s lab at New York University, decided to revisit the phenomenon. Nader had better tools than Lewis had in 1968. Instead of crude electroconvulsive shock, Nader could inject specific protein synthesis inhibitors directly into the amygdala, the brain’s fear center. These drugs, particularly one called anisomycin, prevented cells from making new proteins, a process essential for forming new memories.

Nader’s experiment was elegant. First, he trained rats to fear a tone. Then, after the memory had consolidated, he played the tone again to reactivate the memory. Immediately after, he injected anisomycin into the amygdala. Just as Lewis had found decades earlier, the fear memory was erased. But if he injected the drug without playing the tone, or if he waited too long after playing the tone, the memory remained intact.

The implications were staggering. Consolidated memories weren’t permanent after all. When retrieved, they entered a temporary state of plasticity requiring new protein synthesis to restabilize. Block that process, and the memory could be erased or modified. Nader called this process “reconsolidation.”

The paper, published in Nature in 2000, sparked a revolution. Suddenly, researchers around the world were investigating reconsolidation. They found it in different species, from sea slugs to humans. They found it for different types of memory, from fear to motor skills to drug addiction. The phenomenon was real, robust, and potentially transformative for understanding and treating memory-related disorders.

The Molecular Machinery

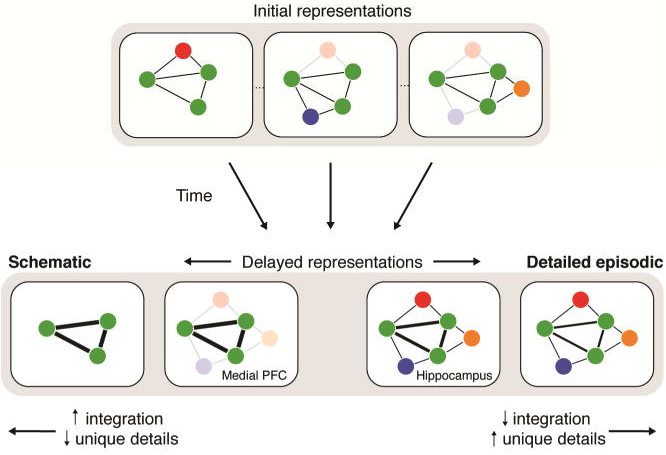

To understand reconsolidation, you need to understand a bit about how memories form in the first place. When you experience something significant, patterns of neurons fire together. If the experience is important enough, these neurons undergo lasting changes that make them more likely to fire together in the future. This is the memory trace or engram.

At the molecular level, this involves a cascade of cellular events. Neurotransmitters activate receptors, which trigger signaling cascades, which activate genes, which produce proteins, which modify synapses. One key player is CREB, a protein that acts like a molecular switch for memory genes. Another is Arc, a protein that helps strengthen specific synapses. The process requires several hours and can be disrupted by protein synthesis inhibitors, which is why a blow to the head can cause amnesia for events just before the injury.

Reconsolidation involves remarkably similar machinery. When a memory is retrieved, the synapses that encode it become active. This activity triggers the same molecular cascades involved in initial consolidation. CREB is phosphorylated, Arc is expressed, new proteins are synthesized. The memory trace literally rebuilds itself.

But here’s the crucial part: during this rebuilding process, the memory is labile. New information can be incorporated. Emotional associations can be strengthened or weakened. In extreme cases, with the right pharmacological or behavioral interventions, the memory can be erased entirely.

The window of plasticity is limited. In most studies, it lasts between one and six hours after retrieval. Miss that window, and the memory reconsolidates in its original form. But hit it right, and you can rewrite the past, at least as it exists in the brain.

The Boundary Conditions

Not every retrieval triggers reconsolidation. This makes evolutionary sense. If every time you remembered something it became fragile and changeable, memory would be unreliable. So the brain has safeguards.

Susan Sara, working in Paris, helped define these boundary conditions. First, the reminder has to be strong enough to fully activate the memory but not so strong as to create a new memory. Second, there needs to be something unexpected, what researchers call a “prediction error.” If everything matches expectations, the memory doesn’t destabilize.

Age of the memory matters too. Newer memories reconsolidate more readily than older ones. Stronger memories, those formed under intense emotion or repeated training, are harder to destabilize but not impossible. The strength of reactivation matters. Too little and the memory doesn’t destabilize. Too much and you might form a new memory instead of updating the old one.

Individual differences play a role. Some people’s memories reconsolidate more readily than others. Stress hormones affect the process. So do genetic variations in memory-related genes. What works for one person might not work for another, a crucial consideration for therapy.

The Clinical Revolution

While neuroscientists were mapping the molecular mechanisms of reconsolidation, psychologist Bruce Ecker was approaching the same phenomenon from a completely different angle. Working with clients in his psychotherapy practice, Ecker had noticed something curious. Sometimes, therapeutic breakthroughs produced sudden, complete, and lasting change. Not gradual improvement, but transformation. Symptoms that had persisted for years would simply disappear.

Ecker and his colleague Laurel Hulley began systematically studying these transformative moments. They found a pattern. The client would access the emotional memory driving their symptoms. Then they would simultaneously experience something that contradicted the memory’s expectation or meaning. Not just intellectually knowing something different, but viscerally experiencing it. When this happened, the symptom would often disappear permanently.

They called this process “memory reconsolidation” without initially knowing about the neuroscience research. When Ecker discovered Nader’s work, he realized they were observing the same phenomenon from different angles. The neuroscientists were erasing fear memories in rats. Ecker was transforming emotional memories in humans. The underlying mechanism was the same.

Ecker formulated what he called the “therapeutic reconsolidation process.” First, activate the target memory along with its emotional components. Second, create a mismatch experience, something that contradicts what the memory expects. Third, repeat this juxtaposition to consolidate the change. This mapped perfectly onto the neuroscience findings.

Explaining the Past

Once you understand reconsolidation, many puzzling aspects of psychotherapy history suddenly make sense. Why did Freud’s patients sometimes have sudden cathartic breakthroughs that produced lasting change? They were retrieving traumatic memories in a context that violated the memory’s predictions, triggering reconsolidation.

Consider systematic desensitization, developed by Joseph Wolpe in the 1950s. The client imagines feared situations while deeply relaxed. The standard explanation was reciprocal inhibition, that you can’t be anxious and relaxed simultaneously. But reconsolidation offers a deeper explanation. The fear memory is activated then reconsolidates in association with a calm state.

Or take empty chair technique from Gestalt therapy. The client has an imaginary dialogue with someone from their past, often a parent. They express things left unsaid, sometimes switching chairs to play both roles. From a reconsolidation perspective, this activates the emotional memory of the relationship while simultaneously violating its expectations. The parent who never listened is now hearing everything. The power dynamic is reversed.

Even cognitive therapy fits the model. When Aaron Beck had depressed patients examine their automatic thoughts, he was having them activate the emotional schemas underlying depression. When they found evidence contradicting these schemas, it created prediction error. The memory reconsolidated with updated information.

EMDR, with its bilateral eye movements, makes more sense through a reconsolidation lens. The traumatic memory is activated while the client simultaneously experiences bilateral stimulation and dual awareness of past and present. This mismatch between the memory’s expectation of danger and the current reality of safety may trigger reconsolidation.

The Modern Experiments

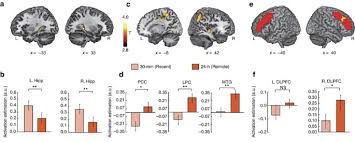

The most dramatic demonstration of reconsolidation in humans came from Merel Kindt’s lab in Amsterdam. Kindt used a Pavlovian fear conditioning paradigm similar to what researchers use with rats. Volunteers saw pictures of spiders paired with electric shock until they showed a fear response to the pictures alone.

The next day, Kindt reactivated the fear memory by showing the spider pictures again. Immediately after, some participants received propranolol, a beta-blocker that interferes with reconsolidation. Others got placebo. On day three, the propranolol group showed dramatically reduced fear responses. Not just subjectively, but in objective measures like skin conductance and startle response.

The effect was specific and lasting. Propranolol only worked if given after memory reactivation. Without reactivation, it did nothing. The fear reduction persisted for months. Most remarkably, declarative memory remained intact. Participants remembered that the spider pictures had been paired with shock. They just no longer felt afraid.

This dissociation between declarative and emotional memory was crucial. You could erase the emotional component of a traumatic memory without erasing the memory itself. This addressed ethical concerns about memory modification. People could remember what happened without being tormented by it.

Other labs extended these findings. Daniela Schiller at Mount Sinai showed you could update fear memories using purely behavioral methods. By introducing new information during the reconsolidation window, she could reduce fear responses without any drugs. This opened the door for purely psychological interventions based on reconsolidation.

Tom Beckers in Belgium demonstrated that even remote, strongly consolidated fear memories could be modified through reconsolidation. The key was using the right retrieval cues and creating sufficient prediction error. Older, stronger memories required more precise targeting, but they weren’t immune to change.

The Addiction Connection

Some of the most promising applications of reconsolidation research involve addiction. Drug memories, the associations between cues and drug effects, drive craving and relapse. These memories are notoriously resistant to extinction. An addict can go through treatment, stay clean for months, then relapse after encountering a drug-associated cue.

Barry Everitt’s group at Cambridge showed that drug memories undergo reconsolidation just like fear memories. When rats were reminded of cocaine-associated cues, then given a protein synthesis inhibitor, they lost their drug-seeking behavior. The effect was specific and lasting. The rats remembered the instrumental response but no longer found drug cues motivating.

Human studies followed. Ravi Das at Cambridge gave recovering alcoholics propranolol after retrieving alcohol-associated memories. The treatment reduced craving and attentional bias toward alcohol cues. Similar studies targeted nicotine addiction and even behavioral addictions like gambling.

The challenge with addiction is that drug memories are extensive and redundant. An alcoholic doesn’t just have one drinking memory but thousands. Each context, each drinking buddy, each emotional trigger represents a separate memory trace. Successful treatment might require targeting multiple memory networks.

The Trauma Protocols

Several groups have developed psychotherapy protocols explicitly based on reconsolidation. Ecker’s Coherence Therapy provides a systematic method for identifying and transforming the emotional learnings maintaining symptoms. The therapist helps the client discover the implicit emotional knowledge driving their symptoms, then creates experiences that contradict this knowledge during memory activation.

Alain Brunet in Montreal developed a protocol combining propranolol with memory reactivation for PTSD. Patients write a narrative of their trauma, then read it aloud after taking propranolol. Repeated sessions progressively reduce the emotional intensity of the memory. Clinical trials show substantial and lasting reduction in PTSD symptoms.

Richard Gray’s Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories protocol uses a sequence of eye movements, visualizations, and somatic interventions designed to maximize prediction error during trauma memory retrieval. Preliminary studies show rapid reduction in trauma symptoms, though more research is needed.

These protocols differ in their methods but share core features. They all involve activating the target memory with its emotional components. They all create some form of prediction error or mismatch experience. And they all work within the reconsolidation window to produce lasting change.

The Mechanisms of Change

Research has identified several mechanisms that can trigger reconsolidation and update memories. Prediction error is crucial. When retrieved information doesn’t match stored information, the memory destabilizes. This can be as simple as expecting danger but experiencing safety, or as complex as discovering that a limiting belief is false.

Interference during reconsolidation can weaken or alter memories. This can be pharmacological, like propranolol blocking noradrenergic signaling, or behavioral, like performing a competing task during the reconsolidation window. The interference doesn’t have to completely block reconsolidation, just alter it enough to change the memory’s emotional impact.

New learning during reconsolidation can update memory content. If you retrieve a memory then immediately learn something that contradicts it, the new information can be incorporated into the reconsolidating trace. This might explain why insight-oriented therapies sometimes produce sudden change. The “aha” moment occurs while the relevant emotional memory is active and reconsolidating.

Somatic interventions might work through reconsolidation. When Peter Levine has trauma clients track sensations while recalling traumatic events, or when Pat Ogden uses sensorimotor approaches, they’re potentially creating prediction error at the body level. The memory expects certain somatic responses that don’t occur or resolve differently.

The Neuroscience Updates

Recent neuroscience research has revealed additional complexity in reconsolidation mechanisms. It’s not just about protein synthesis in the amygdala. The hippocampus, crucial for contextual and episodic memory, undergoes its own reconsolidation. The medial prefrontal cortex, involved in memory suppression and emotion regulation, plays a modulatory role.

Different memory components reconsolidate independently. The who, what, where, when, and emotional components of an episodic memory can be separately modified. This might explain why some therapeutic interventions reduce emotional distress without affecting memory accuracy.

Epigenetic mechanisms are involved. Reconsolidation involves not just new protein synthesis but changes in gene expression patterns. DNA methylation and histone modifications that occurred during initial encoding can be reversed during reconsolidation. This suggests memories are even more modifiable than initially thought.

Neural oscillations coordinate reconsolidation across brain regions. Theta rhythms synchronize the hippocampus and cortex during memory retrieval. Disrupting these rhythms can prevent reconsolidation. Conversely, enhancing them might facilitate therapeutic memory modification.

The Challenges and Controversies

Not everyone is convinced that reconsolidation is the miracle cure for emotional disorders. Some memories, particularly those involving multiple traumatic events or developmental trauma, seem resistant to reconsolidation interventions. The boundary conditions discovered in lab studies don’t always predict what happens in clinical settings.

There’s debate about whether all therapeutic change involves reconsolidation or whether some involves different mechanisms. Extinction learning, forming new inhibitory memories that compete with old ones, remains important. Some researchers argue that what looks like reconsolidation is really just enhanced extinction.

Individual differences are substantial and poorly understood. Why do some people’s traumatic memories readily reconsolidate while others’ don’t? Genetic factors, developmental history, and current stress all seem to play roles, but we can’t yet predict who will respond to reconsolidation-based interventions.

Ethical concerns persist about memory modification. Even if we’re only changing emotional associations rather than factual content, are we altering something fundamental about personal identity? If someone’s trauma shaped who they became, is it ethical to erase that influence? These questions become more pressing as reconsolidation interventions become more powerful.

The Future Directions

Research is moving in several exciting directions. Optogenetics allows researchers to activate and inactivate specific memory engrams with light, revealing the neural substrates of reconsolidation with unprecedented precision. This technology, though currently limited to animal research, is revealing exactly which neurons encode memories and how they change during reconsolidation.

Pharmacological enhancement of reconsolidation is another frontier. Rather than just blocking reconsolidation to weaken memories, researchers are exploring drugs that enhance reconsolidation to strengthen therapeutic learning. D-cycloserine, a partial NMDA receptor agonist, might enhance the incorporation of new information during reconsolidation.

Combination approaches show promise. Using multiple reconsolidation triggers simultaneously, targeting different memory systems in sequence, or combining pharmacological and behavioral interventions might overcome the limitations of single approaches. The goal is personalized protocols based on individual memory characteristics.

Brain stimulation techniques offer new possibilities. Transcranial magnetic stimulation or direct current stimulation applied during memory retrieval might enhance or direct reconsolidation. Early studies show promise for treating depression and PTSD, though much work remains to optimize protocols.

The Clinical Integration

For practicing therapists, reconsolidation research offers both validation and challenge. It validates what many have observed, that transformative change is possible, sometimes rapidly. It explains why certain techniques work and suggests how to make them more effective. But it also challenges therapists to be more precise in their interventions.

Timing matters more than previously thought. Activating a memory without creating prediction error might actually strengthen it through reconsolidation. Creating mismatch experiences outside the reconsolidation window might be ineffective. The casual eclecticism of much psychotherapy might need to give way to more targeted approaches.

The research suggests that the field’s historical divide between insight-oriented and somatic approaches is artificial. Effective therapy might require both cognitive understanding and embodied experience. The memory has to be activated in all its components, cognitive, emotional, and somatic, for reconsolidation to occur.

Training implications are significant. Therapists need to understand not just techniques but the underlying mechanisms. They need to recognize when a memory is activated, how to create appropriate prediction error, and how to work within the reconsolidation window. This requires a different kind of clinical thinking, more precise and mechanistic.

The Broader Implications

Memory reconsolidation has implications beyond psychotherapy. Education might benefit from understanding how to update rather than just overlay previous learning. Criminal justice might reconsider approaches to rehabilitation if criminal behavior is driven by modifiable emotional memories. Even political beliefs and prejudices, to the extent they’re based on emotional learning, might be amenable to reconsolidation-based change.

The discovery challenges fundamental assumptions about the fixity of the past. While we can’t change what happened, we can change how past experiences live in our nervous systems. This is both hopeful and unsettling. Hopeful because it means suffering based on past experience isn’t necessarily permanent. Unsettling because it means our memories, which feel like bedrock truth, are more constructed and reconstructible than we imagined.

The Scientific Process

The reconsolidation story also illustrates how science progresses. Lewis’s original finding in 1968 was ignored because it didn’t fit the dominant paradigm. It took decades and new techniques for the field to accept what was always there. This raises questions about what other dismissed findings might deserve reconsideration.

The convergence of neuroscience and psychotherapy around reconsolidation is notable. Researchers studying molecular mechanisms in rats and therapists observing clinical change in humans independently discovered the same phenomenon. This convergent evidence from multiple levels of analysis strengthens confidence in reconsolidation’s reality and importance.

The translation from basic science to clinical application has been remarkably rapid. Only twenty years elapsed between Nader’s Nature paper and multiple clinical protocols based on reconsolidation. This translation was facilitated by researchers willing to bridge disciplines, combining rigorous neuroscience with clinical sensitivity.

Memory reconsolidation represents a fundamental discovery about how brains work and how people can change. It explains why some therapeutic interventions produce lasting change while others don’t. It suggests new approaches to treating not just PTSD but potentially any condition driven by emotional learning. Most fundamentally, it reveals that the past, as it lives in our brains, is not fixed but continually reconstructed.

The discovery doesn’t mean that change is easy or that all suffering can be simply erased. Many factors affect whether and how memories reconsolidate. Individual differences are substantial. Some memories seem particularly resistant to modification. But the basic finding that consolidated memories can be updated rather than just managed or competed with opens new possibilities for healing.

As research continues, we’re likely to discover additional mechanisms and develop more sophisticated interventions. The crude approaches of today, giving propranolol after memory retrieval or creating mismatch experiences in therapy, might seem primitive compared to future techniques. But the fundamental insight will remain that memory is not a recording but a reconstruction, and that each reconstruction is an opportunity for change.

The philosophers always suspected it, the poets knew it intuitively, and now the scientists have proven it. The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past. It lives in our neurons, reconstructing itself each time we remember. And in that reconstruction lies the possibility of freedom from what has been and transformation into what might be.

0 Comments