For much of the 20th century, the dominant paradigm in psychology was behaviorism, which focused on observable behavior and sought to understand the mind through the lens of stimulus-response conditioning. This approach gave rise to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which remains one of the most widely practiced forms of psychotherapy today.

While CBT has proven effective for certain conditions, particularly anxiety disorders, it is fundamentally limited by its reliance on a narrow, mechanistic view of the psyche that fails to account for the depth, complexity, and paradoxical nature of human consciousness. By prioritizing symptom reduction and behavioral change over the exploration of meaning, CBT and behaviorism often mistake the map for the territory, treating surface-level distress as the root problem rather than as a sign of deeper psychospiritual imbalance.

To truly heal the modern soul, psychotherapy must move beyond the constraints of the behaviorist paradigm and re-engage with the symbolic, emotional, and transpersonal dimensions of the self. This requires a shift towards more integrative, depth-oriented approaches that honor the wisdom of the unconscious and the transformative power of the therapeutic relationship itself. Only by embracing the full spectrum of human experience – from the somatic to the symbolic, the personal to the archetypal – can we hope to address the epidemic of meaninglessness and disconnection that underlies so much of contemporary suffering.

The Behaviorist Worldview and Its Discontents

At the heart of behaviorism is a fundamentally mechanistic view of the human being. Pioneered by thinkers like Ivan Pavlov and B.F. Skinner, behaviorism emerged in the early 20th century as an attempt to make psychology more “scientific” by focusing solely on observable, measurable behavior. The mind itself was seen as a “black box,” unknowable and irrelevant to the prediction and control of behavior, which was understood as a product of environmental conditioning.

This worldview gave rise to a form of therapy oriented around the modification of maladaptive behaviors and thought patterns. In the behaviorist model, psychological distress is the result of dysfunctional learning, whether through classical conditioning (in which neutral stimuli become associated with negative responses) or operant conditioning (in which behaviors are reinforced or extinguished through reward and punishment). The goal of therapy, then, is to identify and change these learned responses through techniques like exposure, cognitive restructuring, and behavioral activation.

While these approaches can be effective for certain presentations, particularly phobias and compulsive behaviors, they are ill-equipped to address the deeper existential and relational roots of much psychological suffering. By focusing narrowly on symptom reduction and surface-level change, CBT often fails to engage with the emotional, symbolic, and transpersonal dimensions of the psyche that give rise to distress in the first place.

The Limits of Symptom-Focused Treatment

One of the central limitations of the behaviorist approach is its tendency to pathologize and medicalize normal human suffering. In the CBT model, painful emotions like anxiety, depression, and grief are seen primarily as symptoms to be eliminated, rather than as meaningful responses to life circumstances that may require deeper exploration and integration.

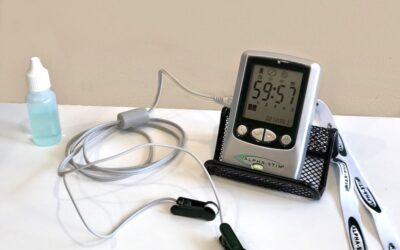

This symptom-focused orientation is reflected in the over-reliance on standardized assessment tools and diagnostic categories in contemporary psychotherapy. Checklists like the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 are used to quickly screen for and quantify depression and anxiety, reducing the rich complexity of human emotional experience to a set of decontextualized, numerical scores. While these tools have their place, they often serve to objectify distress and distance therapists from the lived realities of their clients.

Moreover, by emphasizing symptom reduction as the primary goal of treatment, CBT can inadvertently reinforce the very conditions that give rise to suffering in the first place. For example, a client who has learned to cope with anxiety through avoidance and suppression may experience temporary relief through CBT techniques like relaxation training and thought challenging. However, without addressing the underlying emotional conflicts and relational patterns that fuel the anxiety, these strategies may ultimately serve to maintain the problem by preventing deeper healing and growth.

The psychiatrist and scholar Joel Kovel offers a trenchant critique of this approach in his book “The Age of Desire,” where he argues that psychotherapy’s tendency to prioritize “ego strength” over depth-psychological exploration leads to thepsychological impoverishment of both patients and therapists. By overemphasizing rational self-control and adaptation to external reality, therapies like CBT may inadvertently contribute to the alienation and existential emptiness that characterize modern life.

The Power of the Unconscious

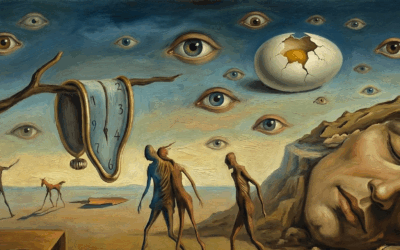

The behaviorist paradigm’s narrow focus on conscious, rational processes fails to account for the profound influence of unconscious factors on human behavior and experience. From a depth psychological perspective, the psyche is not a unitary, transparent entity, but a complex, multi-layered system shaped by powerful forces beyond the reach of the conscious mind.

The psychoanalytic tradition, in particular, has long recognized the centrality of the unconscious in psychological life. Freud’s topographical model of the mind, which divides the psyche into conscious, preconscious, and unconscious levels, suggests that much of our mental activity occurs outside of conscious awareness. Later thinkers like Jung and Lacan expanded on this model, pointing to the existence of a collective unconscious shaped by archetypal patterns and cultural symbols.

Contemporary research in cognitive neuroscience has provided empirical support for the notion of unconscious mental processing. Studies using techniques like priming and implicit association tests have shown that our judgments, decisions, and behaviors are often influenced by stimuli that we are not consciously aware of. This research suggests that the conscious mind is more like the tip of the iceberg, with much of our psychological functioning occurring below the surface.

The failure of behaviorism to engage with the unconscious dimensions of the psyche is particularly problematic when it comes to the treatment of trauma. Traumatic experiences, by their very nature, often involve a breakdown of the normal processes of memory consolidation and integration, leading to the fragmentation and dissociation of mental content. In many cases, traumatic memories are encoded somatically or symbolically, outside of verbal-linguistic processing, making them difficult to access through purely cognitive interventions.

Depth-oriented therapies like psychodynamic therapy, Jungian analysis, Brainspotting, and ETT (emotional transformation therapy) are designed to work directly with the unconscious mind, using techniques like free association, dream analysis, and bilateral stimulation to facilitate the integration of traumatic material. By bypassing the defenses of the rational mind and working with the symbolic language of the psyche, these approaches can help clients access and transform the deeper roots of their suffering.

The Emotional Brain

Another key limitation of the behaviorist approach is its neglect of the central role of emotion in human experience and behavior. While CBT acknowledges the importance of emotional states, it tends to view them primarily as epiphenomena of cognition – byproducts of our thoughts and beliefs that can be altered through rational deliberation.

However, a growing body of research in affective neuroscience suggests that emotions are not merely secondary to cognition, but are in fact primary drivers of behavior and decision-making. The work of Antonio Damasio, for example, has shown that patients with damage to the emotional centers of the brain (particularly the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex) often struggle with decision-making and social functioning, despite having intact cognitive abilities.

This research points to the existence of an “emotional brain” that operates largely independently of the “rational brain,” and that plays a central role in motivating and directing behavior. From an evolutionary perspective, emotions can be understood as adaptive responses that helped our ancestors survive and reproduce in a dangerous world – the fear response, for example, mobilizes the body for fight or flight in the face of threat.

The problem arises when these emotional responses become dysregulated or dissociated from their appropriate contexts, as often happens in cases of chronic stress, trauma, or attachment disruption. In these cases, the emotional brain can become stuck in patterns of hyperarousal or numbness, leading to a range of psychological and physiological symptoms.

CBT’s emphasis on rational disputation and cognitive restructuring may be of limited use in addressing these deeper emotional patterns. While challenging negative thoughts can provide relief in the short term, it does not necessarily address the underlying affective and somatic experiences that give rise to those thoughts in the first place.

Emotion-focused and experiential therapies, by contrast, work directly with the felt sense of emotion in the body, using techniques like focusing, chair work, and expressive arts to help clients access and transform their inner experience. These approaches recognize that emotions are not just mental events, but embodied states that require somatic and relational attunement to fully resolve.

The Wisdom of the Body

The behaviorist model’s emphasis on mental processes fails to account for the profound intelligence and healing potential of the body itself. From a somatic perspective, psychological distress is not just a product of dysfunctional thoughts or behaviors, but a reflection of deeper physiological and energetic imbalances.

The field of somatic psychology, pioneered by thinkers like Wilhelm Reich and Alexander Lowen, views the body as a storehouse of unresolved emotional and traumatic material. When this material is not fully processed and integrated, it can manifest as chronic muscle tension, postural distortions, and other physical symptoms.

Somatic therapies like Hakomi, sensorimotor psychotherapy, and bioenergetics work directly with the body to release this stored tension and promote greater integration and wholeness. These approaches use techniques like mindful tracking, body-based interventions, and movement to help clients develop greater awareness and regulation of their physical experience.

Research in psychoneuroimmunology and epigenetics has also highlighted the powerful role of the body in shaping mental and emotional health. Studies have shown that chronic stress and trauma can alter gene expression and immune function, leading to a range of physical and psychological disorders. Conversely, practices like yoga, meditation, and tai chi have been shown to promote neuroplasticity, emotional regulation, and overall well-being.

The implication is that any truly comprehensive approach to psychotherapy must include a focus on somatic experience and embodiment. By attending to the wisdom of the body and working with the physiological substrates of emotion and memory, therapists can help clients access a deeper level of healing and transformation.

The Transformative Power of Meaning

Perhaps the most fundamental limitation of the behaviorist paradigm is its inability to engage with the deeper questions of meaning and purpose that underlie so much of human suffering. From an existential perspective, psychological distress is not just a matter of maladaptive thoughts or behaviors, but a reflection of the inherent challenges and contradictions of the human condition.

The existential tradition, represented by thinkers like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Sartre, emphasizes the individual’s freedom and responsibility in the face of an absurd and meaningless universe. For the existentialists, the task of therapy is not to eliminate suffering, but to help clients confront the ultimate concerns of existence – death, isolation, freedom, and meaninglessness – and to create a life of authenticity and purpose in spite of them.

Logotherapy, developed by Viktor Frankl based on his experiences in Nazi concentration camps, is a form of existential therapy that focuses specifically on the healing power of meaning. Frankl argued that the primary human drive is not pleasure or power, but the search for meaning and purpose in life. He saw psychological distress as arising from a “noogenic neurosis” – a sense of inner emptiness and lack of meaning that cannot be resolved through conventional psychotherapy.

Logotherapy aims to help clients discover their unique “will to meaning” – the specific values, goals, and responsibilities that give their life a sense of direction and purpose. Through techniques like Socratic dialogue, paradoxical intention, and dereflection, logotherapists help clients shift their focus from their symptoms to the deeper sources of meaning in their lives.

Other meaning-centered approaches, like narrative therapy and constructivist psychotherapy, emphasize the role of language and storytelling in shaping our sense of self and world. These approaches view psychological distress as arising from “problem-saturated” narratives that limit our ability to see new possibilities and generate alternative solutions. By deconstructing these limiting stories and co-creating new, more empowering narratives, therapists can help clients find new meaning and agency in their lives.

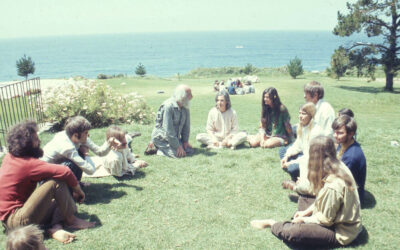

The Therapeutic Relationship as Sacred Space

Finally, the behaviorist model fails to fully recognize the transformative power of the therapeutic relationship itself. From a relational perspective, the healing potential of therapy lies not just in the specific techniques or interventions used, but in the quality of presence and attunement that the therapist brings to the encounter.

Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, provides a framework for understanding how early relational experiences shape our capacity for emotional regulation and interpersonal connection. Securely attached individuals, who have experienced consistent, attuned care from their primary caregivers, tend to have a greater capacity for self-reflection, empathy, and emotional resilience. Insecurely attached individuals, by contrast, often struggle with trust, intimacy, and affect regulation, leading to a range of interpersonal and psychological difficulties.

Attachment-based therapies, like Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) and Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy (AEDP), aim to provide a corrective emotional experience that can help repair early attachment wounds and promote greater security and resilience. These approaches emphasize the role of the therapist as a safe haven and secure base, providing a holding environment in which clients can explore their deepest fears, longings, and vulnerabilities.

From a transpersonal perspective, the therapeutic relationship can be seen as a sacred space – a crucible for the transformation of consciousness itself. Transpersonal therapies, like psychosynthesis and holotropic breathwork, view the therapist-client relationship as a vehicle for accessing higher states of awareness and connection to the divine.

In this view, the therapist is not just a technician applying evidence-based interventions, but a fellow traveler on the path of awakening, offering a compassionate presence and attuned guidance to help the client navigate the depths of their inner world. The goal of therapy is not just symptom relief or behavioral change, but a fundamental shift in the client’s relationship to themselves, others, and the cosmos.

Towards an Integrative, Depth-Oriented Approach The limitations of behaviorism and CBT point to the need for a more integrative, depth-oriented approach to psychotherapy – one that honors the full complexity of the human psyche and recognizes the transformative power of the unconscious, the body, and the therapeutic relationship itself.

Such an approach would draw on the insights of multiple traditions – from psychoanalysis and humanistic psychology to somatic therapies and transpersonal studies – to create a comprehensive framework for understanding and treating psychological distress. It would view symptoms not just as problems to be eliminated, but as meaningful expressions of deeper psychospiritual conflicts and imbalances that require exploration and integration.

This integrative approach would prioritize the cultivation of emotional depth, somatic awareness, and relational attunement, using a variety of experiential and embodied techniques to help clients access and transform their inner world. It would recognize the centrality of meaning and purpose in human life, and work to help clients discover and actualize their unique values and potentials.

Most importantly, an integrative, depth-oriented approach would view the therapeutic relationship as the heart of the healing process – a sacred space in which two individuals come together in a spirit of curiosity, compassion, and mutual discovery. By creating a holding environment of safety, acceptance, and attunement, therapists can help clients develop greater self-awareness, emotional resilience, and capacity for authentic connection.

Ultimately, the goal of psychotherapy is not just to alleviate suffering, but to facilitate the emergence of the client’s deepest truth and fullest potential. This requires a willingness to engage with the full spectrum of human experience – from the depths of the unconscious to the heights of spiritual awakening – and to recognize the inherent wisdom and healing power of the psyche itself.

As the poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote, “The only journey is the one within.” By embracing the depth and complexity of this inner landscape, and by serving as compassionate guides on the path of self-discovery, therapists can help clients find their way home to themselves – and, in so doing, contribute to the healing and transformation of our world.

The crisis of meaning and connection in contemporary society calls for a fundamental reimagining of the role and scope of psychotherapy. While behaviorism and CBT have their place in the treatment of certain conditions, they are fundamentally limited by their mechanistic view of the psyche and their narrow focus on symptom reduction and behavioral change.

To truly heal the modern soul, we must move beyond the constraints of the medical model and re-engage with the profound mysteries of human consciousness. This requires a shift towards more integrative, depth-oriented approaches that honor the transformative power of the unconscious, the body, and the therapeutic relationship itself.

Such approaches recognize that psychological distress is not just a matter of maladaptive thoughts or behaviors, but a reflection of deeper psychospiritual imbalances that require exploration and integration. They view symptoms as meaningful expressions of the psyche’s innate wisdom, pointing the way towards greater wholeness and self-realization.

By embracing the full complexity of the human condition – from the depths of trauma and despair to the heights of creativity and transcendence – therapists can serve as midwives for the emergence of a new paradigm of healing and awakening. This is the great challenge and invitation of our time – to reclaim the soul of psychotherapy and, in so doing, to help birth a world of greater compassion, connection, and meaning.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978).

Patterns of attachment in infancy: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. Putnam.

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. Standard Edition, 4-5.

Greenberg, L. S. (2015). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Kurtz, R. (1990). Body-centered psychotherapy: The Hakomi method. LifeRhythm.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

May, R. (1983). The discovery of being: Writings in existential psychology. W. W. Norton & Company.

Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Houghton Mifflin.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). Mindsight: The new science of personal transformation. Bantam Books.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Additional Resources and Further Reading:

- “The Mind-Brain Relationship” by Regina Pally – This book offers a comprehensive overview of the latest research on the neurobiology of psychotherapy, highlighting the complex interplay between mind, brain, and body in the healing process.

- “The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy: Healing the Social Brain” by Louis Cozolino – Drawing on cutting-edge research in neuroscience and attachment theory, Cozolino shows how psychotherapy can literally rewire the brain for healthier functioning and more fulfilling relationships.

- “The Mindful Therapist: A Clinician’s Guide to Mindsight and Neural Integration” by Daniel J. Siegel – In this book, Siegel applies his groundbreaking theory of interpersonal neurobiology to the practice of psychotherapy, offering practical guidance for cultivating therapeutic presence and attunement.

- “Trauma and the Soul: A Psycho-Spiritual Approach to Human Development and Its Interruption” by Donald Kalsched – Kalsched explores the spiritual dimensions of trauma and healing, drawing on Jungian and psychoanalytic perspectives to illuminate the archetypal forces at work in the psyche.

- “The Healing Power of Emotion: Affective Neuroscience, Development & Clinical Practice” edited by Diana Fosha, Daniel J. Siegel, and Marion Solomon – This collection brings together leading experts in affective neuroscience and experiential psychotherapy to explore the transformative power of emotional experience in the therapeutic process.

- “Awakening Clinical Intuition: An Experiential Workbook for Psychotherapists” by Terry Marks-Tarlow – Marks-Tarlow offers a range of exercises and practices for developing the intuitive, right-brain capacities that are essential for deep therapeutic work, yet often neglected in traditional training programs.

- “Depth Psychology and a New Ethic” by Erich Neumann – In this classic work, Neumann argues for a new ethical framework grounded in the insights of depth psychology, one that recognizes the shadow side of human nature and the need for greater individual and collective responsibility.

- “Revisioning Transpersonal Theory: A Participatory Vision of Human Spirituality” by Jorge N. Ferrer – Ferrer presents a pioneering revision of transpersonal psychology that critiques the field’s traditional focus on individual transcendence in favor of a more relational, embodied, and socially engaged spirituality.

0 Comments