The Wizard Behind the Curtain: The Horseshoe Theory of Consciousness

Think about the end of The Wizard of Oz. Dorothy has traveled the Yellow Brick Road, survived the Wicked Witch, and finally reached the great and powerful Oz, only to discover he’s a fraud, a little man behind a curtain. But here’s the twist. She always had the power to go home. The ruby slippers worked all along. She just had to believe in herself.

This isn’t the hero’s journey we usually talk about in therapy. There’s no descent into the underworld, no confrontation with monsters representing our shadow selves. Instead, Dorothy makes an ascent toward an idealised figure, discovers he’s unworthy of her projection, and then reclaims the power she’d placed in him. She integrates what we might call her positive shadow, those qualities she possessed but couldn’t believe belonged to her.

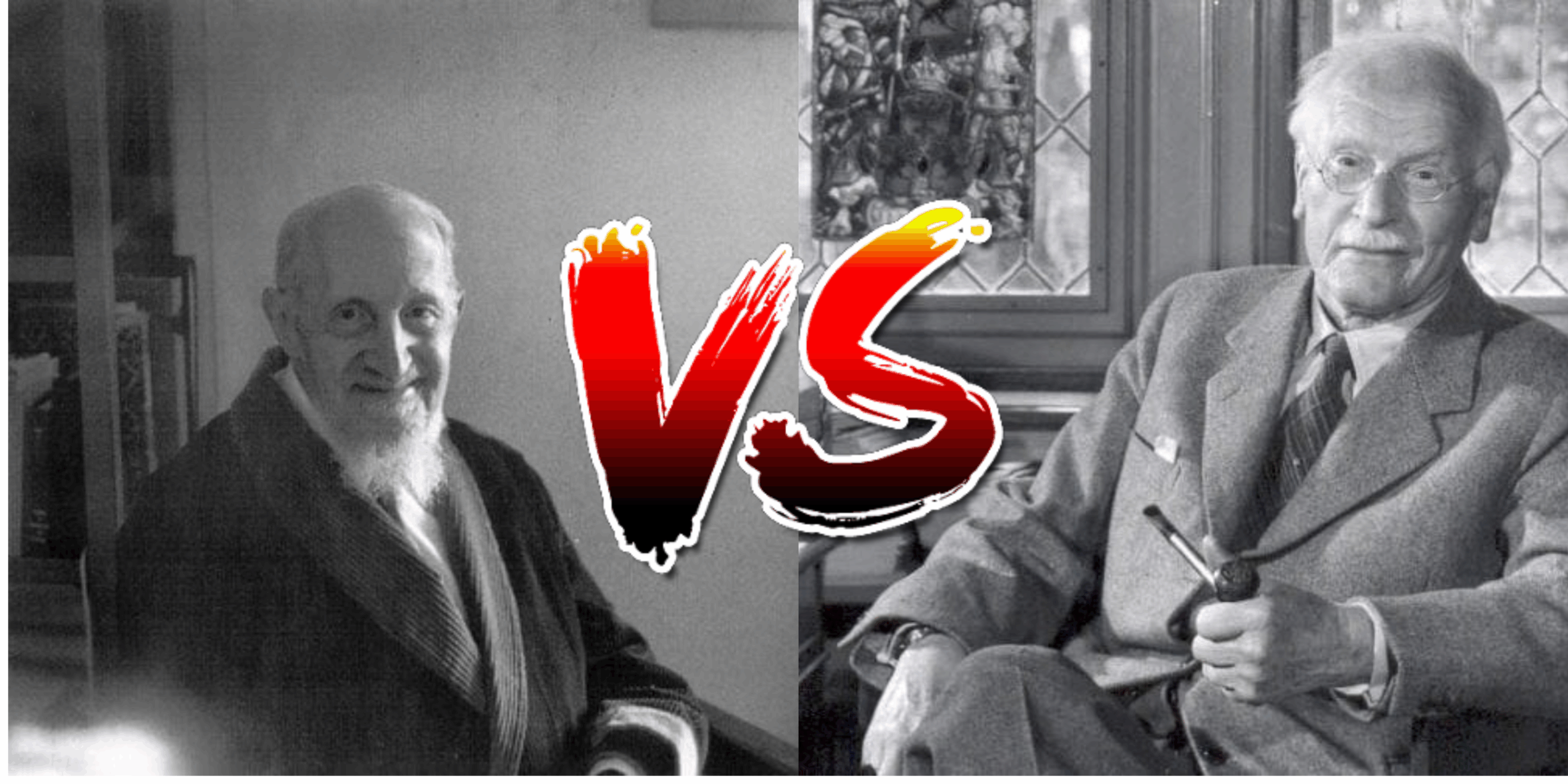

This fundamental difference illuminates the divide between Carl Jung’s depth psychology and Roberto Assagioli’s Psychosynthesis, and it might revolutionize how we understand certain therapeutic journeys.

Jung’s model has become gospel in most therapy rooms. The hero descends into the unconscious, confronts rejected aspects of self, integrates these denied parts, and returns more whole. We encounter the dragon, the monster, the villain, all external representations of internal qualities we’ve repressed because they’re too dark, too shameful, too unacceptable. The racist discovers their own prejudice. The people-pleaser confronts their rage. The perfectionist faces their messiness.

This is powerful work. It’s also incomplete.

Assagioli didn’t just disagree with Jung. He claimed Jung lacked genuine spiritual realization. According to Assagioli, Jung treated spiritual experiences as psychological phenomena to be analyzed rather than as transpersonal realities to be entered. Jung psychologized spirituality; he never truly transcended the psyche. For Assagioli, there was something above the personal and collective unconscious. The Higher Self, the transpersonal dimension. And accessing it required a different journey entirely.

What if the therapeutic journey isn’t always downward? What if sometimes we need to go up?

Consider this pattern that appears everywhere once you start looking. You ascend toward an idealized figure, whether teacher, hero, guru, or parent. You discover they’re flawed, fraudulent, or simply human. Then you reclaim the qualities you projected onto them and integrate your own higher potential.

This is the hero’s journey in reverse. Instead of externalizing your worst parts onto a villain, you externalize your best parts onto a savior. Then you realize they don’t deserve your worship. Those qualities are yours.

The pattern shows up everywhere in our stories. Dorothy’s realization that the Wizard is a fraud parallels Rey discovering Luke Skywalker is broken and disillusioned in The Last Jedi. She must let go of her need for a perfect master and claim her own power. This is why some fans hated that film. It violates the traditional hero’s journey structure they expected.

Po worships the Furious Five and Master Shifu in Kung Fu Panda, only to discover the “Dragon Scroll” is blank. There is no secret. The power was always his belief in himself. Neo meets the Architect in The Matrix Reloaded and realizes even Morpheus’s faith was based on a lie. He must transcend both his mentors and the system to find his own path.

These aren’t stories about disillusionment breeding cynicism. They’re about reclaiming projections of your own greatness.

Unlike Jung’s emphasis on dream analysis, active imagination, and diving into unconscious material, Assagioli’s Psychosynthesis was surprisingly structured and directive. Where Jung might have you dialogue with dream figures, Assagioli would have you practice specific exercises.

The Disidentification Exercise was central to his approach. “I have a body, but I am not my body. I have emotions, but I am not my emotions. I have a mind, but I am not my mind.” The goal was to identify with a witnessing center of pure consciousness, the “I.” In this way psychosynthesis was the opposite of something like Gestalt therapy, where patients identify with a bad parts of the self experience until they burn out and integrate. It might be a prot-form of something like Marsha Linehan’s DBT.

Assagioli would have clients visualize and embody an ideal version of themselves or contemplate figures who embodied qualities they wanted to develop. This wasn’t hero worship but intentional practice in recognizing these qualities as accessible. His guided imagery was highly structured. Clients would ascend a mountain, enter a temple, or meet a “wise being.” Unlike Jungian active imagination which follows the unconscious wherever it leads, these had predetermined spiritual destinations.

The style was more like spiritual coaching than depth psychology. Sessions might include meditation, journaling exercises, and homework. Clients would practice will training through actual exercises, choosing to do difficult tasks or practicing skillful decision-making. It was active, aspirational, and future-focused rather than archeological and past-focused.

In practice, this suggests two distinct therapeutic paths, and recognizing which journey your client is on matters enormously.

Some clients disown their anger, sexuality, selfishness, darkness. They project these onto others who they fear or condemn. They need to descend, confront, and integrate. The risk for them is spiritual bypassing if they skip this shadow work.

Other clients disown their wisdom, power, creativity, brilliance. They project these onto gurus, partners, parents, therapists. They need to ascend, disillusion, and reclaim. The risk for them is getting lost in shadow work and never claiming their gifts.

Some clients do both at different phases. But recognizing which journey your client is on matters.

Here’s something we forget in a trauma-informed field. Curiosity and the desire to grow can bring someone to therapy as much as trauma can.

The client sitting across from you might not be there to heal wounds. They might be there because they sense they’re capable of more. They feel the pull of something greater. They’re hungry for actualization, not just stabilization.

If we only have Jung’s map, we pathologize this client. We go digging for the trauma that “must” be there. We interpret their spiritual hunger as avoidance. We mistake their reaching upward for bypassing.

But what if they’re not running from their humanity? What if they’re running toward their divinity?

This doesn’t mean trauma isn’t present. It means trauma isn’t always the primary story. Sometimes the primary story is “I know I’m meant for something more, and I don’t know how to get there.” That’s not a wound to heal. That’s a calling to answer.

Assagioli reminds us that therapy isn’t just about becoming less broken. It’s also about becoming more magnificent.

But here’s the danger Assagioli didn’t always address. His path risks shadow avoidance and even psychotic breaks.

When you focus exclusively on ascending to the Higher Self without integrating the personal shadow, several things can happen. Using “transcendence” to avoid dealing with rage, grief, trauma, or difficult emotions. “I’ve moved beyond anger” often means “I’ve repressed my anger and called it enlightenment.”

Identifying with the Higher Self before you’ve done the human work can lead to narcissistic inflation. “I am divine” without “I am also petty, jealous, and wounded” creates a brittle, fragile identity.

The disidentification exercise can become pathological dissociation in trauma survivors or those prone to it. You’re not transcending; you’re leaving.

Reaching too far, too fast into transpersonal realms without a grounded ego structure can trigger psychosis. The boundaries between self and other, real and imagined, human and divine can dissolve in terrifying ways.

This is why traditional spiritual paths had years of preparation, moral training, and community containment before advanced practices. Assagioli’s techniques, divorced from this context and used by people seeking shortcuts, could be destabilizing.

Jung’s path has equal and opposite dangers. The shadow can overwhelm you.

Some clients spend decades in analysis, always finding another layer of trauma, another wound, another shadow aspect. They become professional patients, their identity wrapped up in brokenness.

Facing the darkness without a vertical dimension pulling you upward can lead to meaninglessness. If there’s nothing transcendent, if it’s all just wounded ego and biological drives, why bother?

“I’m not angry, I am anger. I’m not depressed, I am depression.” The shadow work meant to integrate instead becomes the whole identity.

Descending into the underworld is only useful if you can return. Some get lost down there. Depression, addiction, suicidal ideation all lurk in unintegrated shadow work without a counterbalancing force.

The shadow can become seductive. Clients and therapists can mistake wallowing for depth, morbidity for authenticity.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth. Both paths can lead to delusion, just from opposite directions.

Assagioli’s delusion sounds like “I am the Higher Self. I have transcended my ego. I am pure consciousness.” Meanwhile, your marriage is failing, you’re alienated from your body, and you can’t handle criticism without collapsing. You’ve confused transcendence with avoidance.

Jung’s delusion sounds like “I have integrated my shadow. I’ve done the work. I see my darkness clearly.” Meanwhile, you’ve become so identified with your wounds that you can’t imagine wholeness. You’ve confused insight with transformation and mistake endless analysis for growth.

The ascending path risks detachment from reality through inflation and dissociation. The descending path risks detachment from reality through despair and fragmentation. Both can make you feel like you’re doing profound psychological work while actually taking you further from authentic human functioning.

In esoteric traditions, there’s a distinction between the Left-Hand Path and the Right-Hand Path. Jung’s work represents the Left-Hand Path, descent into darkness, integration of the taboo, embracing the full spectrum of self, individual sovereignty through confronting what’s forbidden. Assagioli’s work represents the Right-Hand Path, ascent toward light, alignment with higher purpose, transcendence of ego, realization of divine potential.

But wait. What if Assagioli’s ascending journey itself contains both paths?

The Right-Hand version of Assagioli’s ascent looks like what we’ve been describing. You project your nobility onto a guru or teacher. You discover they’re human. You reclaim your own wisdom, compassion, and spiritual authority. You integrate these positive qualities with humility and grace. The disillusionment is gentle, the reclamation is peaceful. You realize the teacher was always pointing you back to yourself.

But there’s a Left-Hand version of this same ascending journey that Assagioli barely acknowledged, and it’s far more dangerous and potent.

In the Left-Hand ascent, you don’t just project your light onto the authority figure. You project your divine darkness, your sacred transgression, your holy rebellion. Think of Lucifer before the fall, the most beautiful angel who dared to claim equality with God. The projection isn’t about wisdom or compassion. It’s about power, sovereignty, the ability to create and destroy reality itself.

When you discover the wizard is a fraud in this path, you don’t gently reclaim your projected qualities. You overthrow the entire cosmic order. You realize that not only is the wizard not worthy of worship, but that the very structure that placed him above you was a lie. The reclamation becomes an act of rebellion against the hierarchy itself.

This is the path of the magician who doesn’t just want to find their Higher Self but to become God. Not in the gentle Buddhist sense of recognizing your Buddha nature, but in the Promethean sense of stealing fire from the heavens. You’re not integrating your positive shadow. You’re reclaiming your divine authority to rewrite the rules of reality.

The danger here isn’t gentle inflation or spiritual bypassing. It’s complete megalomaniacal break with consensus reality. When you realize the guru is false, you don’t just reclaim your wisdom. You declare yourself the new guru. When you see behind the curtain, you don’t go home to Kansas. You take over Oz.

This Left-Hand ascent appears in different mythologies. Satan’s rebellion wasn’t a descent into shadow but an ascent that went too far, claiming the throne rather than just reclaiming projection. The Tower of Babel wasn’t about integrating shadow but about ascending to heaven to become gods. Icarus didn’t fall because he descended into darkness but because his ascent ignored the natural order.

Modern spiritual teachers who’ve had psychotic breaks often follow this Left-Hand ascending path. They start by projecting divine authority onto their teacher. They have a realization that the teacher is flawed. But instead of humbly reclaiming their projection, they declare themselves the new messiah. They didn’t integrate their positive shadow. They identified with it completely.

The Right-Hand Assagioli practitioner uses the disidentification exercise to find the stable “I” that witnesses all experience. The Left-Hand practitioner uses it to dissolve all boundaries between self and cosmos, declaring “I am That” not as recognition but as cosmic coup.

The Right-Hand version visualizes meeting wise beings to recognize these qualities within. The Left-Hand version visualizes devouring these beings to steal their power. Not integration but consumption. Not recognition but usurpation.

Where Right-Hand ascent seeks alignment with higher will, Left-Hand ascent seeks to become the only will. Where Right-Hand seeks service to the transpersonal, Left-Hand seeks dominion over it.

Both paths reclaim projection from the idealized figure. But one does it through humility, recognizing “I too possess these qualities.” The other does it through what we might call divine narcissism, declaring “I alone possess these qualities.”

This explains why some people have such different experiences with psychedelics or spiritual practices. The same practice that leads one person to gentle self-recognition leads another to messianic delusion. They’re not doing the practice wrong. They’re on a different hand of the same path.

Jung accused right-hand spirituality of being escapist, of avoiding the messy human stuff. Assagioli accused Jung of never making genuine contact with the transpersonal, of staying trapped in psychological reductionism.

They were both right. And both wrong.

In my mind Jung protects pilgrims on the path to healing better than Assagioli’s for those on the left hand path. Meanwhile Jungian therapy often struggles to build language and metaphors for patient who are on the right hand path. This mirror’s their disagreements. While publicly cordial, Jung even wrote an intro to one of Assagliolis’s books, the two men disagreed privately. Assaglioli criticised Jung’s empericism. Assaglioli thought that Jung lacked the essential directions to strengthen the will of a patient.

On the other hand, Jung warns against prematurely identifying psychological content with metaphysical or spiritual realities. Though he does not name Assagioli directly, he remarks that attempts to “spiritualize psychology” risk inflating the ego or bypassing the shadow. Jung saw Assagioli’s optimism about human “higher self” development as psychologically premature, he believed integration required full confrontation with the unconscious and shadow first.

Despite remarkably similar psychologies on paper both men had extremely different relationships to their shadow and their projections. Assaglioli saw the future in a much more Aristotelian upward slope to higher societal striving towards potential. Jung focused on the Platonic forms latent in culture. Jung, perhaps more accurately, saw the terrors the collective shadow held if it was not integrated.

Maybe the real journey is a spiral. You descend to integrate shadow, then ascend to claim higher self. You descend deeper to integrate spiritual shadow like ego inflation and bypassing, then ascend higher to actualize transpersonal potential.

You can’t genuinely ascend if you’re running from your darkness. But you also can’t just wallow in shadow without some vertical aspiration pulling you forward.

The client who’s spent years in shadow work, excavating every childhood wound, might need to ask what would happen if they stopped looking for what’s wrong and started reclaiming what’s magnificent.

The client who’s spiritual but avoidant might need to consider whether their ascension is bypassing the human work that would make their spirituality real.

When your client idealizes you, two things might be happening. They might be projecting parental figures, unmet needs, dependency. Or they might be projecting their own potential wisdom, strength, and capacity.

The work isn’t always to analyze the projection. Sometimes it’s to hand it back. “This quality you see in me. Where might you already possess it?”

For the ascending client, ask whether they can stay in their body. Can they feel anger without spiritualizing it? Are they connected to other humans or floating above relationship?

For the descending client, ask whether they can imagine a future. Is there any light in their cosmology? Are they so identified with wounds that wholeness feels fake?

For both, ask whether they’re more functional or less. Can they work, love, create? Or has their “journey” become a way to avoid living?

Assagioli and Jung weren’t really opposites. They were looking at different phases of human development. Jung mapped the descent; Assagioli mapped the ascent. Both are essential. Both are dangerous when taken to extremes.

The hero doesn’t just slay the dragon. Sometimes the hero must fire the wizard. And sometimes the hero must do both, in alternating rhythm, for a lifetime.

Both journeys require courage. Both risk failure and delusion. And both, when balanced, lead to the same destination. Becoming fully yourself. Integrated shadow and actualized light, human and divine, broken and brilliant.

So the next time your client says, “I just don’t have what they have,” consider whether they do. Consider whether the journey isn’t about finding that missing piece but about realizing they’ve been carrying it all along.

But also consider whether they’re ready. Have they done the human work that makes the divine work safe? Or are they trying to fly before they can walk?

0 Comments