You’ve been in therapy for six months. Every week, you sit across from a perfectly nice therapist who nods sympathetically as you describe your symptoms. They teach you breathing exercises for your panic attacks. They help you identify cognitive distortions. They encourage you to journal about your feelings. And every week, you leave feeling like you’re putting Band-Aids on bullet wounds.

What nobody told you – what your well-meaning therapist might not even realize – is that trauma therapy is a completely different animal from regular therapy. It’s not just therapy with the word “trauma” slapped on front. It requires specialized training, a different understanding of the brain and body, and approaches that might seem bizarre compared to traditional talk therapy. More importantly, regular therapy applied to trauma can actually make things worse, re-traumatizing you in ways that are subtle but profound.

The search for a “trauma therapist near me” isn’t just about finding someone who’s willing to listen to your trauma story. It’s about finding someone who understands how trauma fundamentally rewires your nervous system, changes your brain structure, and lives in your body in ways that can’t be reached through conversation alone. It’s about finding someone who knows that your “irrational” responses are actually perfectly rational responses to what you’ve survived.

What Makes a Therapist “Trauma-Informed”

True trauma-informed therapy starts with understanding that trauma isn’t just what happened to you – it’s what happens inside you as a result of what happened to you. It’s the way your nervous system got stuck in survival mode. It’s the way your brain learned to see danger everywhere. It’s the way your body holds the memory even when your mind has tried to forget.

A trauma-informed therapist understands that your nervous system is running the show. You’re not choosing to overreact to that trigger – your amygdala hijacked your prefrontal cortex before you even registered what was happening. You’re not being dramatic when a certain smell sends you into a panic – your body is remembering something your conscious mind might not have access to. You’re not weak for freezing when confronted – your nervous system is doing exactly what it learned to do to keep you safe.

This understanding changes everything about how therapy is conducted. A trauma-informed therapist knows that pushing you to tell your trauma story before you’re resourced and stable can flood your system and reinforce the trauma pathways. They understand that your window of tolerance – the zone where you can process without getting overwhelmed or shutting down – might be narrow, and their job is to help you widen it gradually, not blast through it.

Safety isn’t just a nice idea in trauma therapy; it’s the foundation everything else is built on. A trauma-informed therapist spends significant time establishing safety – in the relationship, in your body, in the therapy space. They know that without felt safety, your nervous system won’t allow healing to happen. Your survival brain needs to know, on a deep biological level, that this person and place are safe before it will let down its guard.

This might look like spending sessions just getting comfortable in the space, practicing grounding exercises, or building resources before ever touching trauma content. To someone expecting to dive into their trauma story immediately, this might feel slow or even avoidant. But it’s actually precision work – building the container strong enough to hold what needs to be processed.

Trauma-informed therapists are also trained to recognize and work with dissociation. They understand that “checking out” isn’t rudeness or resistance – it’s a survival strategy your nervous system employs when things get too intense. They know how to recognize when you’re dissociating, how to help you come back to the present, and how to titrate the work so you stay within your capacity.

They understand trauma responses beyond fight or flight. Freeze, fawn, and flop are equally valid survival responses, each with their own wisdom and challenges. If you’re a fawner who compulsively people-pleases to avoid conflict, they won’t just tell you to “set boundaries.” They’ll understand that your nervous system equates conflict with life-threatening danger and work with you to gradually build capacity for healthy assertion.

Cutting-Edge Trauma Modalities Explained

Let’s dive into the actual methods that can reach trauma where it lives. These aren’t your grandmother’s therapy approaches – some of them might sound like science fiction. But they’re grounded in our evolving understanding of neuroscience and the biology of trauma.

Brainspotting is based on the principle “where you look affects how you feel.” Discovered by David Grand in 2003, it uses the visual field to access the subcortical brain where trauma is stored. Your therapist helps you find eye positions – “brainspots” – that connect to traumatic activation in your body. Then, instead of talking about the trauma, you simply hold that eye position while your brain naturally processes and releases the trapped material.

What makes Brainspotting different is that it bypasses the thinking brain entirely. You don’t need to have a coherent narrative of your trauma. You don’t even need to know what you’re processing. Your brain knows, and given the right conditions, it knows how to heal itself. Sessions might involve sitting in silence for long periods, just holding an eye position while internal processing happens. To an outside observer, it might look like nothing is happening. Inside, your brain is doing profound reorganization.

I’ve seen Brainspotting work for clients who’ve tried everything else. One client, a combat veteran, had done years of talk therapy, CBT, even some EMDR, but still couldn’t sleep through the night without nightmares. After three Brainspotting sessions, focusing on a spot that activated the sensation in his chest where the fear lived, the nightmares stopped. He couldn’t explain why or how – it just shifted.

EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) might be the most researched trauma therapy we have. It uses bilateral stimulation – originally eye movements, but also tapping or audio tones – to help your brain reprocess traumatic memories. The bilateral stimulation seems to activate the same processing that happens during REM sleep, when your brain naturally consolidates and integrates memories.

In EMDR, you don’t just talk about trauma – you reprocess it. You hold the traumatic image in mind while following your therapist’s finger back and forth, or holding buzzers that alternate between your hands. The memory doesn’t disappear, but it loses its emotional charge. It becomes something that happened, not something that’s still happening every time you remember it.

What’s remarkable about EMDR is how it can work even when you don’t fully remember the trauma. Your therapist can work with body sensations, emotional fragments, or even just the negative beliefs trauma left behind. “I’m not safe,” “I’m powerless,” “It’s my fault” – these beliefs can be targets for EMDR even if you can’t access the specific memories that created them.

Somatic Experiencing, developed by Peter Levine, is based on the observation that animals in the wild don’t get PTSD. A gazelle chased by a lion shakes it off and goes back to grazing. Humans, with our complex brains and social conditioning, interrupt this natural discharge process. The survival energy gets trapped in our nervous system, creating trauma symptoms.

SE teaches you to track sensations in your body with curiosity rather than judgment. That tension in your shoulders isn’t just stress – it might be your body still bracing for impact. That collapse in your chest isn’t just depression – it might be your body still playing dead. By gently attending to these sensations and allowing them to complete their natural cycle, the trapped survival energy can finally discharge.

This work is incredibly gentle. Unlike some trauma therapies that can feel like ripping off a bandage, SE is about building capacity slowly. You might spend a session just noticing the difference between tension and relaxation in your hand. This isn’t avoidance – it’s teaching your nervous system that it’s safe to feel again, safe to complete what was interrupted.

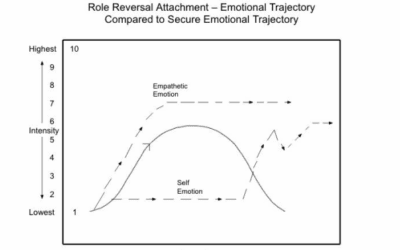

Internal Family Systems (IFS) recognizes that trauma creates internal fragmentation. Parts of you get stuck in the trauma, frozen in time, carrying burdens they were never meant to carry. You might have a part that’s still seven years old, terrified and alone. Another part might be the teenage protector who learned to use anger to keep people at distance. Another might be the perfectionist who believes if you’re good enough, bad things won’t happen.

IFS doesn’t pathologize these parts. Every part, even the ones causing problems, has a positive intention. The angry part is trying to protect you. The anxious part is trying to keep you safe. The numb part is trying to help you survive overwhelming pain. In IFS, you learn to relate to these parts with curiosity and compassion, to understand their roles, and ultimately to help them release the burdens they carry.

What’s powerful about IFS is how it explains the internal chaos trauma survivors often experience. That inner critic isn’t you – it’s a part trying to protect you from judgment. The self-sabotage isn’t weakness – it’s a part that doesn’t believe you deserve good things. By differentiating these parts from your core Self, you can begin to lead your internal system with compassion rather than being hijacked by traumatized parts.

Neurofeedback is like physical therapy for your brain. Trauma changes brainwave patterns, often leaving the brain stuck in high-alert beta waves or dissociative theta waves. Neurofeedback uses EEG sensors to monitor your brainwaves in real-time, then uses visual or auditory feedback to train your brain toward healthier patterns.

You might watch a movie that only plays when your brain produces calm alpha waves. Or play a game that rewards your brain for reducing anxiety-related beta waves. Over time, your brain learns to produce healthier patterns on its own. It’s not about thinking differently – it’s about actually changing the electrical activity in your brain.

For some trauma survivors, especially those with developmental trauma that shaped their brain’s formation, neurofeedback can create changes that talk therapy alone couldn’t achieve. It’s particularly powerful for symptoms like hypervigilance, dissociation, and emotional dysregulation that have become hardwired into the nervous system.

Why Traditional Therapy Can Fail Trauma Survivors

Here’s the hard truth that many therapists don’t want to admit: traditional talk therapy can actually be harmful for trauma survivors. Not because therapists mean harm, but because approaches designed for non-traumatized nervous systems can overwhelm and re-traumatize already dysregulated systems.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, the gold standard for many mental health issues, often falls short with trauma. CBT assumes you can think your way to better feelings and behaviors. But trauma doesn’t live in the thinking brain – it lives in the survival brain, the parts that operate below conscious awareness. You can know intellectually that you’re safe now, that the trauma is over, that your thoughts are “distorted,” and still have your body react as if danger is imminent.

Challenging trauma-related thoughts as “cognitive distortions” can actually be invalidating. That hypervigilance that CBT wants to label as catastrophizing? It’s what kept you alive. That assumption that people will hurt you? It’s based on real experience. Having a therapist tell you these thoughts are “irrational” can feel like being gaslit all over again.

The homework-based approach of CBT can also be problematic for trauma survivors whose executive functioning is compromised by chronic stress. Being unable to complete thought logs or behavioral assignments can trigger shame, reinforcing the belief that they’re failing at therapy like they fail at everything else.

Traditional insight-oriented therapy assumes that understanding equals healing. But you can have all the insight in the world about how your childhood shaped your current patterns and still be triggered into a flashback by a smell, a sound, a tone of voice. Insight doesn’t retrain your amygdala. It doesn’t discharge trapped survival energy. It doesn’t integrate fragmented parts of self.

There’s also the risk of premature trauma exploration. A well-meaning therapist asks you to tell your story, to process your feelings about what happened. But without proper resourcing and stabilization, this can flood your system with more than it can handle. You leave therapy feeling raw, exposed, and destabilized, then spend the week until your next session trying to stuff everything back in the box.

The “just talking about it” approach assumes that verbal processing is sufficient for healing. But traumatic memories are often stored as fragments – sensations, images, emotions without words. Trying to force these fragments into a coherent narrative can be like trying to describe a nightmare that doesn’t follow logical rules. The pressure to make sense of something that doesn’t make sense can itself be traumatizing.

Many traditional therapists also underestimate the somatic component of trauma. They might acknowledge that you feel anxiety in your body but still focus primarily on your thoughts about the anxiety. Meanwhile, your body is screaming unheard, holding patterns and memories that no amount of talking will shift. You might leave therapy intellectually understanding your trauma but still jumping at sudden noises, still unable to tolerate physical intimacy, still feeling unsafe in your own skin.

PTSD vs. Complex PTSD Treatment Differences

Not all trauma is created equal, and the distinction between PTSD and Complex PTSD is crucial for effective treatment. Single-incident PTSD – from a car accident, a natural disaster, a single assault – is what most people think of when they hear “trauma.” The nervous system was stable, something terrible happened, and now it’s dysregulated. Treatment can focus on processing that specific incident and restoring the nervous system to its previous baseline.

Complex PTSD is a different beast entirely. It develops from prolonged, repeated trauma, especially in childhood when the nervous system is still developing. This isn’t about processing a single bad thing – it’s about a nervous system that developed within trauma, that never had a chance to establish healthy baseline functioning. The trauma isn’t an event; it’s the entire context in which you developed.

If you have C-PTSD, your symptoms go beyond flashbacks and hypervigilance. You might struggle with emotional regulation, swinging from numbness to overwhelming intensity. Relationships feel simultaneously essential and terrifying. You might have a fragmented sense of self, unsure who you really are beneath all the survival adaptations. Shame isn’t just a feeling – it’s the core belief that you are fundamentally flawed.

Traditional PTSD treatment often focuses on processing traumatic memories. But with C-PTSD, which memories do you process? The entirety of your childhood? That time when you were four? Or seven? Or thirteen? The trauma is woven throughout your development, shaping your nervous system, your attachment style, your sense of self and others.

This is why phase-oriented treatment is crucial for C-PTSD. Phase one is all about stabilization and safety – building resources, learning regulation skills, establishing secure relationships. This phase might take months or years. Only when you have sufficient internal and external resources do you move to phase two – processing traumatic material. Phase three involves integration and rebuilding your life beyond trauma.

For single-incident PTSD, approaches like EMDR or prolonged exposure might be sufficient. The trauma is processed, integrated, and resolved. But C-PTSD requires a more comprehensive approach. You’re not just processing memories – you’re building capacities you never had the chance to develop. You’re learning to regulate emotions, to maintain relationships, to have a coherent sense of self.

The question “how is PTSD caused” has different answers depending on the type. Single-incident PTSD is caused by an overwhelming event that exceeds your nervous system’s capacity to cope. Your brain couldn’t process and file the memory properly, so it remains active, unintegrated, triggering your survival responses.

C-PTSD is caused by repeated exposure to inescapable trauma, particularly in relationships where you depend on the person hurting you. Your developing nervous system adapts to chronic threat. Hypervigilance becomes your baseline. Dissociation becomes your refuge. These aren’t symptoms to eliminate – they’re adaptations that allowed you to survive.

When we ask “what events can cause PTSD,” we need to broaden our understanding beyond the obvious traumas. Yes, combat, sexual assault, and life-threatening accidents cause PTSD. But so does chronic emotional neglect. Repeated bullying. Medical trauma. Racial trauma from living in a systemically oppressive society. Any experience that overwhelms your capacity to cope and leaves you feeling helpless and alone can be traumatic.

For C-PTSD, it’s often not events but environments. Growing up with a parent with untreated mental illness. Living in poverty with chronic threat of instability. Being a parentified child responsible for emotional caretaking of adults. These ongoing circumstances shape a nervous system that never learns safety, that never develops secure attachment, that operates from survival rather than growth.

Accessing Specialized Trauma Therapy

Finding a truly trauma-informed therapist requires more detective work than just Googling “trauma therapist near me.” You need to know what questions to ask, what certifications matter, and what red flags to watch for. This isn’t about being picky – it’s about protecting yourself from well-meaning but inadequately trained therapists who could inadvertently cause harm.

Start with certifications. Look for therapists certified in specific trauma modalities: EMDR (through EMDRIA), Somatic Experiencing (SEP designation), Brainspotting (through Brainspotting International), IFS (through the IFS Institute). These certifications require extensive training, supervision, and continuing education. A weekend workshop doesn’t make someone a trauma specialist.

Ask about their specific trauma training. How many hours? Through what organizations? How recently? Trauma treatment is rapidly evolving, and someone who learned about trauma in graduate school twenty years ago might be working from outdated models. You want someone committed to ongoing learning in trauma specialization.

Inquire about their experience with your type of trauma. Someone excellent with single-incident trauma might be out of their depth with complex developmental trauma. Someone skilled with combat trauma might not understand religious trauma. It’s okay to ask, “Have you worked with clients with similar experiences to mine?” Their answer should be honest and nuanced, not a blanket “I treat all trauma.”

Watch for therapists who immediately want to dive into trauma processing. A skilled trauma therapist will prioritize stabilization and resourcing first. They should assess your current capacity, your support systems, your coping strategies. If someone wants to do EMDR in your first session, run. That’s not trauma-informed; it’s reckless.

Pay attention to how they handle boundaries and pacing. A trauma-informed therapist respects your autonomy and your right to say no. They check in regularly about how you’re doing. They notice when you’re approaching your window of tolerance and help you regulate before you’re overwhelmed. They understand that going slow is going fast when it comes to trauma.

Red flags include therapists who promise quick fixes, who claim one approach works for all trauma, or who seem uncomfortable with intense emotions. Be wary of therapists who push forgiveness as necessary for healing, who minimize your trauma (“others have had it worse”), or who seem fascinated by trauma details in a way that feels voyeuristic rather than therapeutic.

Now let’s talk about the financial reality. BCBS coverage for trauma therapy varies by plan, but most cover the standard trauma treatments like EMDR and CBT for PTSD. However, some of the more innovative approaches like neurofeedback might not be covered, or might be covered under different codes. Call your insurance and ask specifically about coverage for the modality you’re interested in.

Here’s a insider tip: many trauma specialists don’t take insurance directly but will provide superbills for out-of-network reimbursement. If you have out-of-network benefits with BCBS, you might pay upfront and get reimbursed for a percentage. It requires more paperwork, but it dramatically expands your options for specialized care.

For those without BCBS or with high deductibles, sliding scale fees make trauma therapy accessible. Many trauma therapists reserve spots for reduced-fee clients because they understand that trauma often impacts financial stability. Trauma disrupts education, employment, relationships – all the things that contribute to financial security. Ethical trauma therapists recognize this and build accessibility into their practice models.

Don’t be ashamed to ask about sliding scale. You’re not taking advantage or being cheap. You’re prioritizing your healing despite financial constraints, and that takes courage. A therapist who makes you feel bad about needing reduced fees is showing you they’re not safe for other vulnerabilities either.

Consider group therapy for trauma as a cost-effective option. Trauma thrives in isolation and heals in connection. Group therapy provides not just professional support but peer support from others who get it. Many trauma-focused groups are covered by BCBS at lower copays than individual therapy. You might do individual therapy biweekly and group weekly, maximizing support while managing costs.

0 Comments