African American Folk Arts as a Means to Heal Inter-Generational Trauma

The African American experience in the United States is a testament to the capacity of the human spirit to transmute suffering into beauty. African American folk arts and traditions have played a vital role in shaping the cultural landscape of the United States, particularly in the Deep South. These practices—encompassing music, quilting, storytelling, ironworking, and culinary arts—have served as powerful means of expression, community-building, and resilience in the face of centuries of oppression, trauma, and displacement.

Psychologically, these arts function as more than just aesthetic hobbies; they are vehicles for processing intergenerational trauma. Research into epigenetics and historical trauma suggests that the stress of systemic oppression can be passed down physiologically. However, culture is also passed down. By tracing the roots of these traditions back to Africa and exploring their evolution in the context of American slavery and the Jim Crow South, we gain a deeper understanding of how African Americans have used creativity to assert humanity and resist dehumanization. In Birmingham, Alabama, a city forged in iron and civil rights struggle, these traditions remain a living, breathing part of the community’s mental health and identity.

A Jungian Perspective on Folk Arts: Soul-Making in the South

James Hillman, a prominent American psychologist and the founder of archetypal psychology, offers valuable insights into the significance of folk culture and myth. Hillman’s work emphasizes that the “soul” of a person or a people is not found in the abstract, but in the gritty, messy details of daily life and imagination.

In his seminal book The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling, Hillman explores the “acorn theory,” which posits that each individual (and by extension, each culture) is born with a unique essence that seeks fulfillment. For the African American diaspora, this essence was often violently suppressed by external forces. Hillman argues that when the “acorn” is crushed, the soul expresses itself through symptom or myth. Folk art acts as the bridge, turning the “symptom” of trauma into the “myth” of survival.

Hillman’s essay The Myth of Analysis suggests that engaging with cultural myths—like the trickster archetype embodied by Anansi and Brer Rabbit—allows individuals to tap into a reservoir of collective wisdom. This is not merely intellectual; it is therapeutic. When a community participates in call-and-response singing or communal quilting, they are engaging in what Hillman calls “Soul-making”—the act of deepening one’s connection to the world and one’s history, thereby healing the fragmentation caused by trauma.

Music and Quilting: The Geometry of Healing

Two of the most significant and enduring African American folk traditions are music and quilting. These practices are particularly resonant in Alabama, home to the world-renowned Gee’s Bend quilters. Located just a few hours south of Birmingham, the women of Gee’s Bend developed a quilting style that broke all the rules of European symmetry, opting instead for bold, improvisational geometric abstractions that mirror the rhythms of Jazz.

The Psychology of the Quilt

Quilting emerged as a practical necessity for enslaved African Americans, yet it evolved into a sophisticated language of survival. The “Underground Railroad Quilt Code” theory suggests that specific patterns were used to signal safety or danger to escaping slaves. Psychologically, the act of quilting is an act of re-integration. It involves taking scraps—discarded, torn, and useless fragments—and stitching them together into a unified, functional whole. This is a profound metaphor for the trauma survivor’s journey: taking the fragmented memories of a painful past and stitching them into a new narrative of warmth and protection.

The Rhythms of Birmingham

Music in Birmingham has served a similar function. From the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame to the legacy of Tuxedo Junction, music provided a container for emotions that were too dangerous to speak aloud. African American music, encompassing spirituals, blues, and jazz, utilizes polyrhythms and blue notes (flattened thirds and sevenths) to express the complexity of the human condition.

The “Call and Response” structure found in Black gospel and work songs is a powerful therapeutic tool. It validates the individual’s voice (“The Call”) by integrating it into the support of the community (“The Response”). This combats the isolation that trauma often induces. In the steel mills of Birmingham, such as Sloss Furnaces, work songs were not just for morale; they were essential for safety, synchronizing the movements of workers handling dangerous molten iron.

Bottle Trees and Haint Blue: The Architecture of Protection

Trauma often leaves individuals feeling unsafe in their own environments. African American folk traditions addressed this through spiritual technologies of protection, deeply rooted in African cosmology.

The Bottle Tree: Originating in the Congo region of Africa, the tradition involves placing glass bottles on the branches of trees. It was believed that evil spirits (or “haints”) would be attracted to the reflection in the glass, become trapped inside the bottle, and be destroyed by the morning sun. In the psychological landscape of the South, this served as a tangible boundary against the “evil” of systemic racism and personal misfortune. You can still see bottle trees in gardens across Birmingham, from Fountain Heights to Avondale, serving as modern sculptures of spiritual defense.

Haint Blue: If you walk through the historic neighborhoods of Birmingham, you will notice many porch ceilings painted a specific shade of pale, blue-green. This is “Haint Blue.” Rooted in Gullah Geechee culture, the color was believed to trick spirits into thinking the ceiling was water (which spirits cannot cross) or the sky (causing them to fly away). This architectural choice created a “safe container” for the family, a psychological sanctuary where the external traumas of the Jim Crow South could not enter.

Anansi and Brer Rabbit: The Trickster as Survival Guide

African American storytelling traditions are another rich source of cultural resilience. One of the most prominent figures is the Trickster. In West African folklore, Anansi the Spider is a god of knowledge who uses cunning to defeat stronger opponents. In the American South, Anansi transformed into Brer Rabbit.

These stories were not merely entertainment for children; they were survival manuals for adults living under the regime of slavery. Brer Rabbit, physically weaker than Brer Fox or Brer Bear, wins through wit, linguistic dexterity, and psychological manipulation. For a population that was legally and physically disempowered, the Trickster offered a psychological outlet for aggression and a blueprint for subverting authority.

In Jungian terms, the Trickster represents the Shadow—the chaotic, rule-breaking aspect of the psyche that is necessary for change. By identifying with the Trickster, African Americans could access a sense of power and agency that was denied to them in the social hierarchy. Birmingham’s own Civil Rights Institute documents how this “Trickster” energy—the ability to outmaneuver a rigid system—was utilized in the strategic planning of the Children’s Crusade and Project C.

The Physiology of Folk Rhythm: Regulating the Nervous System

Enslaved Africans brought with them a sophisticated understanding of rhythm that modern neuroscience is only beginning to understand. The banning of drums in many parts of the enslaved South (because slave owners feared they were used to communicate) led to the development of hambone or Juba dance—using the body itself as a percussion instrument.

From a trauma therapy perspective, rhythmic movement and drumming are powerful regulators of the autonomic nervous system. Trauma is stored in the lower brain (the brainstem), which speaks the language of sensation and rhythm, not logic. The complex polyrhythms of African American folk music help to synchronize the brain hemispheres and discharge the “freeze” energy of trauma. This is why somatic therapies often look to these ancient traditions for guidance on how to move trauma out of the body.

Birmingham: A Living Museum of Resilience

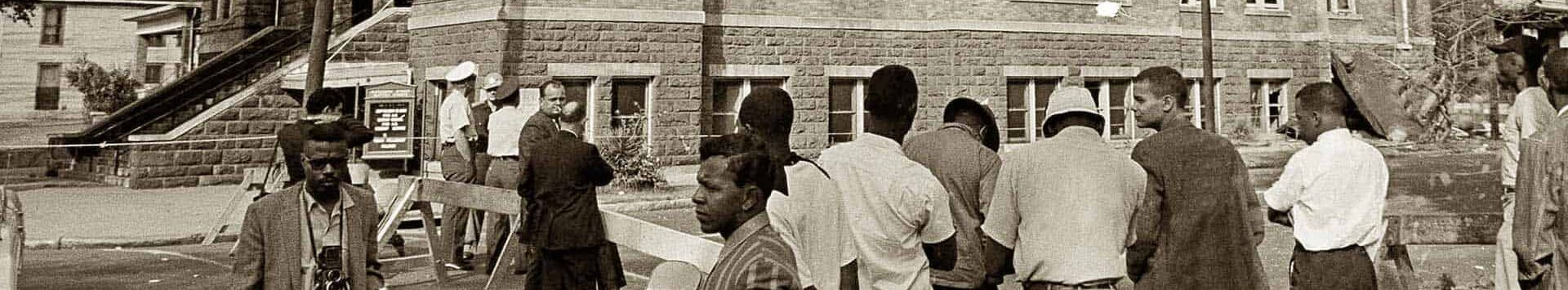

Birmingham, Alabama, stands as a unique intersection of these folk traditions. As an industrial hub, it drew Black workers from the rural Black Belt, bringing the blues of the Delta and the quilting traditions of Gee’s Bend into an urban, industrial context. This migration created a vibrant culture of resilience that fueled the Civil Rights Movement.

According to census data, from 1910 to 1970, six million African Americans moved from the rural South to the urban North and West, yet Birmingham remained a critical cultural anchor. Today, with a population that is approximately 68.5% African American (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022), the city is reclaiming these folk arts not as relics of the past, but as tools for future healing. Events like the Magic City Classic or festivals at the Birmingham Museum of Art continue to showcase how these traditions evolve.

As we continue to grapple with the ongoing legacy of racism and inequality, it is vital to recognize African American folk arts as high-level psychological technologies. They are the mechanisms by which a people preserved their souls in a world that sought to crush them. By embracing these traditions, we honor the resilience of the ancestors and provide a roadmap for healing the generations to come.

Explore More on Culture and Psychology in Birmingham:

- African American Writing and Music: Combating Generational Trauma

- Spider Martin: Visualizing the Struggle for Civil Rights

- Southern Gothic Literature and the Jungian Shadow

- The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

- Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark

Bibliography

- Baker, H. A. (1984). Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature: A Vernacular Theory. University of Chicago Press.

- Brown, E. B. (1989). “African-American Women’s Quilting: A Framework for Conceptualizing and Teaching African-American Women’s History.” Signs, 14(4), 921-929.

- Hillman, J. (1996). The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. Random House.

- Hurston, Z. N. (1935). Mules and Men. J. B. Lippincott Company.

- Levine, L. W. (1977). Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Thompson, R. F. (1983). Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. Random House.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). QuickFacts: Birmingham city, Alabama. Retrieved from census.gov.

- Wahlman, M. S. (2001). Signs and Symbols: African Images in African American Quilts. Tinwood Books.

0 Comments