Mary Main’s Groundbreaking Attachment Research

Mary Main (1943-2023) transformed our understanding of attachment through her revolutionary contributions to developmental psychology and attachment research. As a protégé of Mary Ainsworth at Johns Hopkins University, Main expanded attachment theory beyond its original three categories by discovering a fourth pattern known as disorganized/disoriented attachment and developing the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) to assess attachment representations across generations. Her work revealed how early attachment experiences create enduring patterns that manifest not only psychologically but also somatically, setting the stage for contemporary body-based therapeutic approaches. Main’s influence extends far beyond her direct contributions, inspiring researchers and clinicians such as Daniel Siegel, Allan Schore, Steven Vazquez, and Karl Heinz Brisch to develop innovative approaches that integrate attachment theory with neuroscience and somatic interventions.

The Discovery of Disorganized Attachment

While replicating Ainsworth’s Strange Situation research in the 1970s at UC Berkeley, Main noticed that approximately 10% of infants displayed behaviors that didn’t fit neatly into Ainsworth’s original three categories of secure, anxious-avoidant, and anxious-resistant attachment. These children exhibited contradictory behaviors, such as approaching the caregiver while displaying apprehension, freezing or stilling behaviors, or sequential and simultaneous displays of contradictory behavioral patterns. Main recorded these “odd” behaviors meticulously, refusing to follow Ainsworth’s initial suggestion to force-fit these children into existing categories.

In 1986, Main, together with Judith Solomon, formally introduced the disorganized/disoriented (D) attachment classification after reviewing discrepant infant behaviors in Strange Situation tapes from various research groups including the Grossmanns, Mary J. O’Connor, Elizabeth Carlson, Leila Beckwith, and Susan Spieker. This discovery has been described by Michael Rutter as one of the five great advances to psychology contributed by attachment research. Main and Erik Hesse proposed that disorganized attachment results from a paradoxical situation where the attachment figure is simultaneously the source of and solution to the infant’s alarm. This paradox can occur when caregivers are frightening, frightened, or dissociated due to their own unresolved trauma. Research has shown that approximately 48% of infants in the D category have experienced some form of neglect or abuse, though Main and Hesse emphasized that frightening or frightened caregiver behavior represents “one highly specific and sufficient, but not necessary, pathway to D attachment status.”

The Adult Attachment Interview

In the early 1980s, Main and her graduate students Nancy Kaplan and Carol George developed the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) as part of the Berkeley Social Development Study. This semi-structured interview assesses adults’ state of mind regarding attachment by examining how they narrate their early attachment experiences. The development process involved a “guess and uncover” system where researchers conducted parent interviews, guessed what the babies might act like in situations based on what was said, then compared the children’s behaviors and the parents’ responses to refine their understanding. Through this iterative process, they developed the AAI that many mental health professionals use today.

Main’s work showed that securely attached adults have coherent life narratives and can reflect on their experiences with balanced perspective, while insecurely attached adults show various forms of incoherence in their attachment narratives. The AAI revealed that parents’ attachment representations strongly predicted their infants’ attachment patterns, demonstrating intergenerational transmission of attachment. This finding linked attachment patterns to the integration of memory systems and the ability to mentalize about attachment experiences. The research showed that approximately 45% of adults were not securely attached, a figure that has profound implications for understanding relationship difficulties and the transmission of attachment patterns across generations.

The Legacy of Mary Main: Influence on Contemporary Researchers and Clinicians

Mary Main’s revolutionary work has profoundly influenced a generation of researchers and clinicians who have expanded our understanding of attachment and its neurobiological underpinnings. Daniel Siegel, who has been photographed with Main at various conferences, integrated her insights into his interpersonal neurobiology framework, emphasizing how secure attachment promotes neural integration and how mindfulness practices can help develop “earned secure attachment.” Siegel frequently cites Main’s work in explaining how attachment patterns shape the developing brain and how therapeutic interventions can create new neural pathways even in adulthood.

Allan Schore, often referred to as the “American Bowlby,” has built extensively on Main’s discoveries about disorganized attachment, focusing on how early attachment experiences literally shape the developing right brain and affect regulation systems. Schore’s work on the neurobiology of attachment trauma directly extends Main’s insights about frightened and frightening caregiving behaviors, demonstrating at a neurobiological level how these experiences create lasting impacts on the autonomic nervous system and stress response systems. His research has shown that the right hemisphere of the brain, which processes emotional and relational information, develops in direct response to early attachment experiences, validating Main’s observations about the profound impact of early relationships.

Steven Vazquez, developer of Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT), represents another avenue through which Main’s work has influenced contemporary practice. Vazquez explicitly describes ETT as an “attachment-based interpersonal approach” that recognizes how early attachment experiences create patterns stored both psychologically and somatically. His innovative use of light, color, and visual brain stimulation to access and transform attachment-related trauma builds on Main’s understanding that attachment experiences involve multiple levels of processing beyond conscious awareness. Vazquez’s work demonstrates how Main’s insights about the pre-verbal and implicit nature of attachment experiences have inspired entirely new therapeutic modalities.

Other researchers influenced by Main include Marinus van IJzendoorn, who has noted that Main’s concept of “state of mind” regarding attachment is fundamentally about “the direction and organization of attention and memory,” inspiring his research on genetic polymorphisms that influence the dopamine system and attachment. Giovanni Liotti further developed Main’s ideas about disorganized attachment and dissociation, while Mary True and Kazuko Behrens, both students of Main, extended her work cross-culturally, demonstrating the universality of attachment patterns while respecting cultural variations.

The influence of Main’s work extends to clinical practice through numerous therapeutic innovators. Diana Fosha’s Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy (AEDP) builds on attachment theory to create transformative therapeutic experiences. Pat Ogden’s Sensorimotor Psychotherapy directly addresses how attachment patterns are held in the body, while Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing, though not exclusively focused on attachment, recognizes the fundamental importance of early relational experiences in shaping nervous system regulation.

Emotional Arcs and Somatic Storage in Attachment

The Concept of Emotional Arcs

Attachment experiences create what can be conceptualized as “emotional arcs”—patterns of emotional activation, expression, and resolution that become templates for future emotional experiences. In secure attachment, these arcs follow a natural trajectory: emotions arise in response to needs or threats, are expressed and met with attuned responses, reach a peak, and then resolve, returning the system to baseline. This complete arc allows for emotional integration and the development of effective self-regulation.

However, in insecure and disorganized attachment patterns, these emotional arcs become disrupted or incomplete. Parts of the emotional experience may be split off, suppressed, or amplified, creating fragmented or dysregulated patterns that persist into adulthood.

Somatic Storage of Attachment Patterns

Contemporary neuroscience reveals that attachment patterns are encoded not just in explicit memory and cognitive schemas, but deeply embedded in implicit memory systems that include somatic, sensory, and procedural components. The body literally holds the history of our attachment experiences through:

- Muscle tension patterns: Chronic bracing or collapse reflecting defensive strategies

- Breathing patterns: Restricted or dysregulated breathing associated with anxiety or dissociation

- Autonomic nervous system settings: Hypervigilance or hypoarousal states

- Movement patterns: Approach-avoidance conflicts embodied in physical gestures

- Visceral responses: Gut reactions and bodily sensations that signal relational safety or threat

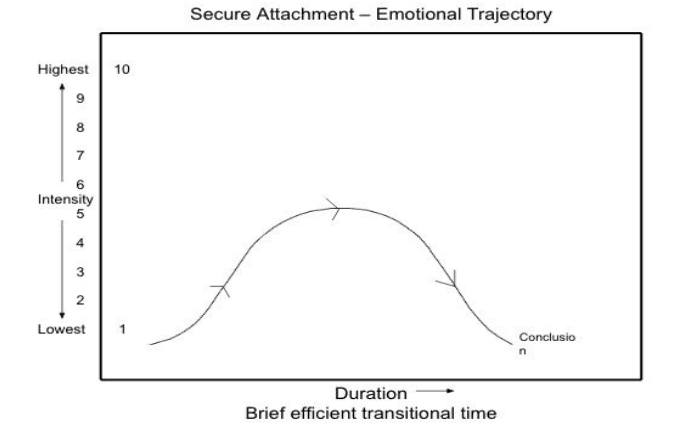

Attachment Styles and Their Somatic Manifestations: Main’s Classifications and Brisch’s Extensions

Mary Main’s research identified specific behavioral and emotional patterns associated with each attachment style, which manifest somatically throughout the lifespan. Research has shown that secure attachment, representing approximately 55% of the population according to Main’s studies, is characterized by resilience, appropriate grief responses, and positive affect most of the time. These individuals had parents who responded warmly, were accessible, attuned, and responsive to their emotional needs. As adults, they speak coherently, possess good recall of their history, and can move through distress until it reaches conclusion. Their emotional arcs follow a bell-shaped curve, with emotion elevating to medium intensity before decreasing until permanently concluded.

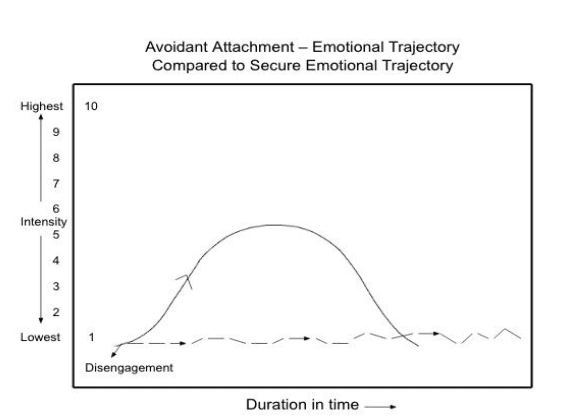

The avoidant attachment pattern, comprising approximately 20% of the population, develops when parents are unaffectionate, rigid, and insensitive or rejecting of the child’s signals. These children appear friendly and independent but are indifferent to the parent’s absence or return and are non-emotionally expressive. As adults, they exhibit non-disclosing, non-feeling, minimizing patterns, intellectualization, and selective idealization. They may appear secure but in crises will have avoidant, detached responses. Their somatic profile includes chronic muscle tension, particularly in the back, shoulders, and jaw, restricted breathing patterns, and a tendency to “hold” or contain bodily sensations.

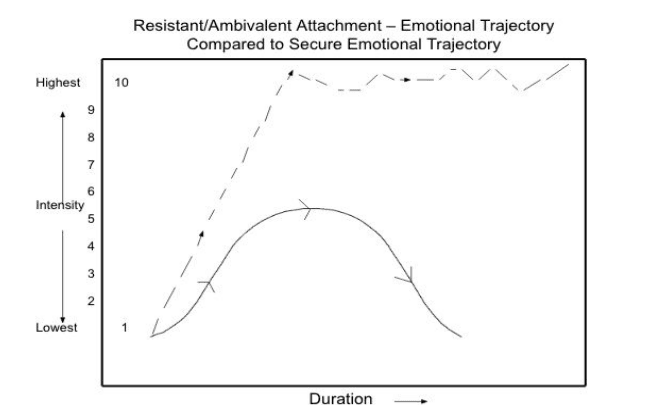

The anxious-ambivalent or resistant attachment pattern, affecting approximately 10% of the population, emerges when parents are unresponsive or inconsistently responsive to the child’s emotional needs and regard the child as a nuisance. These children are preoccupied with attachment issues, easily distressed by separation, not easily comforted, and will cling or resist. As adults, they express excessive intense emotion with rapid escalation, achieve little or no resolution to distress, exhibit extreme worry, and may possess suicidal ideation. Their somatic manifestations include alternating patterns of tension and collapse, irregular breathing, heightened sensitivity to bodily sensations, and difficulty self-soothing.

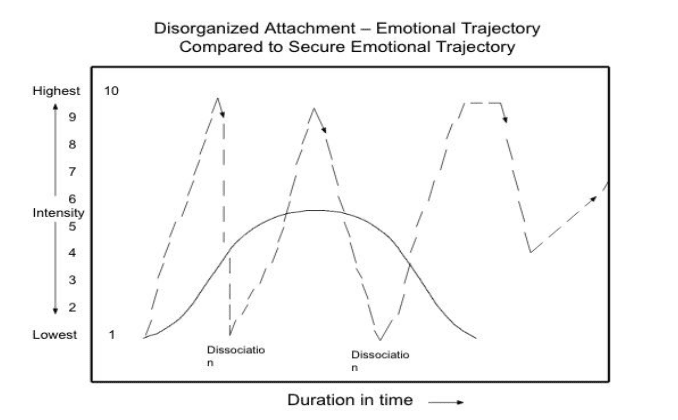

The disorganized attachment pattern, identified by Main and Solomon as affecting approximately 15% of the population, occurs when parents exhibit maltreatment, possess a history of trauma themselves, or display frightened or frightening behavior. These children show contradictory, confusing behavior, dazed expressions, interrupted movements, and alternate between being expressive and “freezing.” As adults, they exhibit fragmented or incoherent narrations, disconnected content, intense emotional expression, dissociation, and chaotic presentations. Somatically, they experience sudden shifts between hyper- and hypoarousal states, freezing responses, dissociative phenomena, and fragmented body awareness.

Karl Heinz Brisch’s Expanded Attachment Classifications

Building on Main’s foundational work, Karl Heinz Brisch identified additional subcategories of attachment patterns that provide more nuanced understanding of how attachment manifests across the lifespan. His contributions are particularly valuable for recognizing variations within the major attachment categories and their specific somatic and therapeutic implications.

Brisch identified the undifferentiated attachment disorder as a form of avoidant attachment where individuals avoid actual intimacy despite high degrees of social interaction. These children were friendly toward everyone but difficult to console, having experienced emotional neglect often in foster care settings. As adults, they disclose too quickly, sometimes causing others to distance, exhibit excessive verbalization with tangents, lack depth of intimacy, and may take the peacemaker role. Their somatic pattern involves a diffuse bodily awareness that lacks clear boundaries, reflecting their interpersonal style.

The exaggerated attachment disorder, a subcategory of avoidant attachment viewed as codependent, develops when parents have experienced unresolved loss, inadvertently use their children as their secure base, and panic when children show independence. These children exhibit excessive clinging and are very anxious and inconsolable. As adults, they resist bonding to new people but have difficulty with separation once committed, stay in bad relationships too long, continue attachment to people who are gone or deceased, and are loyal but possessive. Somatically, they experience chronic tension patterns that reflect their holding on, with restricted breathing that mirrors their fear of letting go.

Inhibited attachment disorder, a subcategory of resistant/ambivalent attachment, emerges when parents are physically or verbally abusive. These children appear inhibited and excessively compliant with attachment figures, can be more open with strangers, and show fear-based repression and suppression of emotional expression. As adults, they exhibit entrenched inhibited behaviors, are anxious, phobic, nervous, and shy, finding closeness frightening. Their bodies reflect this inhibition through chronic muscular bracing, shallow breathing, and a tendency toward somatic anxiety symptoms.

Aggressive attachment disorder, another subcategory of resistant/ambivalent attachment, develops when parents exhibit violent behavior and frequent angry moods. These children show aggressive, violent reactions to separation, their behavior often provokes rejection, yet they are calmed when attachment takes place. As adults, they exhibit chronic hostility leading to negative reactions which reinforces their negative beliefs about others, hold adversarial views, believe they have justifiable anger, blame others, are suspicious, and sometimes explosive. Somatically, they carry chronic muscular tension associated with anger, elevated baseline arousal, and difficulty down-regulating their nervous system.

Role reversal attachment, a subcategory of avoidant attachment, occurs when parents experience significant psychological victimization, repeated loss without adequate coping skills, and lack appropriate boundaries with the child. These children focus on the needs of others like parents or siblings and assume parental responsibility prematurely. As adults, they are nice and likeable but possess an external locus of control, have an excessive sense of responsibility with poor boundaries, and worry obsessively about others. Their somatic profile includes chronic tension in the upper body from carrying others’ burdens and restricted breathing patterns that reflect their self-sacrifice.

Psychosomatic attachment disorder represents another subcategory of avoidant attachment where emotional responses are repressed and redirected into physical symptoms. Parents exhibited pronounced avoidance of the child’s emotional expression and a distancing attitude. These children showed repeated, often legitimate physical symptoms. As adults, they exhibit frequent and chronic physical symptoms while appearing in control and not emotionally expressive. Their entire somatic experience becomes the container for unexpressed emotions.

Finally, Brisch identified patterns of no signs of attachment, occurring when children experience abandonment or severe neglect. These individuals may not seek human contact and develop various forms of self-soothing. As adults, they may show overt inability to bond, narcissistic and exploitive patterns, antisocial behavior, and lack of empathy. Somatically, they often exhibit profound disconnection from bodily sensations and an absence of the normal physiological responses to interpersonal connection.

Emotional Trajectories in Attachment: Visual Representations and Clinical Applications

Understanding Emotional Arcs Through Attachment Diagrams

The visual representation of emotional trajectories provides clinicians with powerful tools for understanding how different attachment patterns manifest in the processing of emotional experiences. These diagrams, based on attachment research, illustrate the fundamental differences in how individuals with various attachment styles experience, express, and resolve emotional activation.

The secure attachment emotional trajectory demonstrates the optimal emotional response to distressing events. The bell-shaped curve shows emotion and emotional expression elevating to a medium level of intensity (approximately 5 on a 10-point scale) and then decreasing until it reaches permanent conclusion. This trajectory is characterized by brief, efficient transitional time and complete resolution. Clinically, this pattern indicates healthy emotional regulation where the individual can fully experience emotions, express them appropriately, and move through them to completion. Therapists can use this as a baseline for comparison with other attachment patterns and as a goal for therapeutic progress.

The resistant/ambivalent attachment emotional trajectory reveals a dramatically different pattern. The diagram shows rapid escalation to maximum intensity (10 on the scale) with a fragmented, incomplete resolution pattern indicated by the dashed line that remains elevated. This visual representation captures how individuals with this attachment style experience excessive intense emotion with rapid escalation but achieve little or no resolution to distress. The extended duration and lack of conclusion reflect their ongoing preoccupation with attachment-related concerns. Clinically, this helps therapists understand why these clients may present with chronic anxiety, extreme worry, and difficulty achieving emotional closure.

The avoidant attachment emotional trajectory, when compared to the secure trajectory, shows marked minimization of emotional experience. The dashed line remains low (between 1-2 on the intensity scale) throughout the duration, with a notation of “disengagement” at the beginning. This visual representation illustrates how avoidant individuals truncate their emotional experience, maintaining a disconnection from their internal states. The diagram helps clinicians recognize that what appears as emotional stability may actually represent profound disconnection from authentic emotional experience.

The disorganized attachment emotional trajectory presents the most complex pattern, showing multiple spikes of high intensity (reaching 9-10) with periods of dissociation marked on the diagram. The fragmented nature of the line, alternating between solid and dashed segments, represents the discontinuous experience of emotion characteristic of disorganized attachment. The multiple peaks without resolution and the notation of dissociative episodes illustrate why these individuals experience such difficulty in emotional regulation and integration.

Clinical Applications of Emotional Trajectory Diagrams

These visual representations serve multiple clinical functions. For assessment purposes, therapists can use these diagrams to help clients identify their own emotional patterns. Showing clients these trajectories can facilitate recognition of their attachment style in a non-threatening, educational manner. Many clients experience relief when they see their emotional patterns represented visually, as it validates their experience while offering hope for change.

In treatment planning, understanding a client’s typical emotional trajectory informs intervention strategies. For secure attachment clients, therapy can proceed with standard emotional processing techniques, as these individuals have the capacity to move through complete emotional arcs. For resistant/ambivalent clients, interventions must focus on containing and titrating intense emotions, breaking down overwhelming emotional floods into manageable components, and teaching skills for achieving resolution.

For avoidant clients, the therapeutic task involves gradually increasing tolerance for emotional intensity, helping them stay present with feelings rather than disengaging. The visual representation helps therapists recognize that pushing for emotional expression too quickly will likely increase avoidance. Instead, therapy must proceed slowly, celebrating small increases in emotional awareness and expression.

For disorganized attachment, the trajectory diagram illustrates why traditional emotional processing may be contraindicated initially. The multiple spikes and dissociative episodes indicate a need for stabilization before processing traumatic material. Therapists must first help these clients develop capacity for emotional regulation and maintain awareness during emotional activation.

Brisch’s Subcategory Trajectories and Clinical Implications

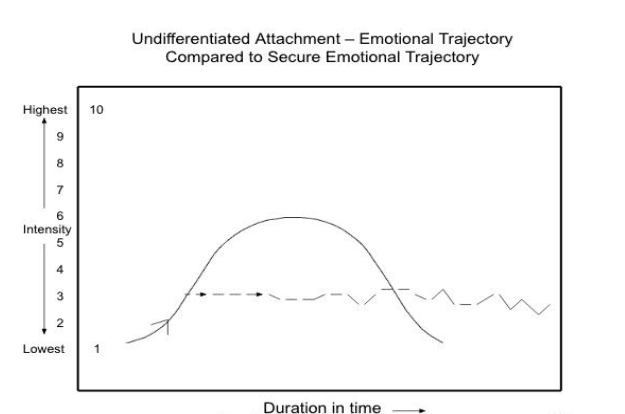

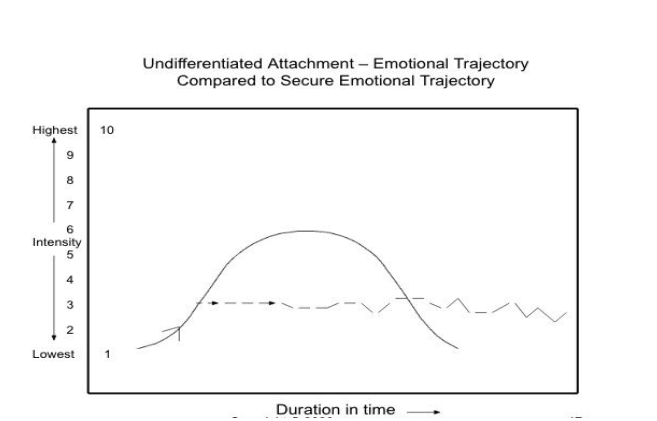

The emotional trajectories for Brisch’s subcategories provide even more nuanced clinical information. The undifferentiated attachment trajectory shows a pattern similar to avoidant attachment but with slight elevation (2-3 on the scale) that remains constant over time without resolution. This persistent low-level activation without conclusion reflects their pattern of superficial engagement without genuine emotional connection.

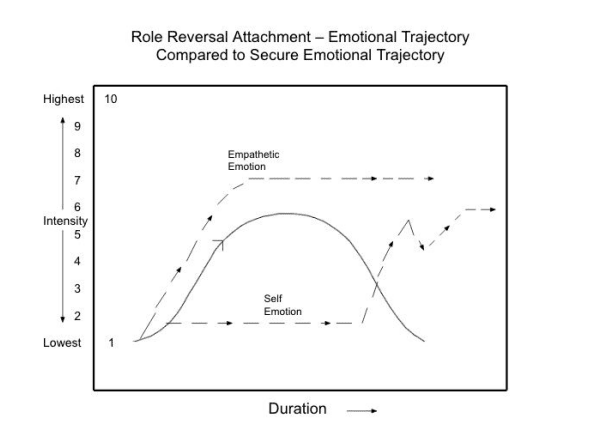

The role reversal attachment trajectory uniquely shows two lines: one representing “empathetic emotion” that remains elevated at 7, and another representing “self emotion” that remains suppressed at 1-2. This dual trajectory powerfully illustrates how these individuals maintain high attunement to others’ emotions while disconnecting from their own, explaining their chronic pattern of caretaking at the expense of self-awareness.

Integration with Personality Disorders

These attachment-based emotional trajectories provide crucial insights into personality disorder presentations. Borderline personality disorder often correlates with disorganized attachment patterns, and the trajectory diagram helps explain the emotional dysregulation, fear of abandonment, and identity disturbance characteristic of this disorder. The multiple intensity spikes and dissociative episodes shown in the diagram mirror the affective instability and dissociative symptoms seen in borderline presentations.

Narcissistic personality disorder frequently correlates with avoidant attachment patterns, particularly the “no signs of attachment” subcategory identified by Brisch. The emotional trajectory for this pattern would show minimal fluctuation, remaining at a constant low level without genuine engagement or resolution. This helps clinicians understand the emotional emptiness and lack of empathy characteristic of narcissistic presentations.

Dependent personality disorder often emerges from exaggerated attachment patterns, where the emotional trajectory would show persistent elevation when separated from attachment figures, with resolution only occurring through reunion or reassurance. This visual representation helps therapists understand the intense anxiety these individuals experience around autonomy and separation.

Therapeutic Use of Trajectory Diagrams

Clinicians can use these diagrams as psychoeducational tools, showing clients their typical patterns and contrasting them with secure attachment trajectories. This visual approach often resonates more deeply than verbal explanations, as clients can literally see the difference between their patterns and healthier alternatives.

Progress monitoring becomes more concrete when therapists and clients can track changes in emotional trajectories over time. As therapy progresses, clients with resistant/ambivalent attachment might notice their intensity peaks becoming less extreme and their resolution time decreasing. Avoidant clients might observe gradual increases in their emotional intensity, moving from the 1-2 range toward the healthy 5-6 range of secure attachment.

For somatic therapists particularly, these diagrams provide a bridge between cognitive understanding and bodily experience. Therapists can help clients notice where in their body they experience different points on their emotional trajectory. For instance, a client might recognize that the rapid escalation phase corresponds with chest tightness and shallow breathing, while the incomplete resolution phase manifests as chronic shoulder tension.

The integration of these visual tools with somatic approaches creates powerful therapeutic possibilities. During Brainspotting sessions, therapists might reference these trajectories to help clients understand what they’re experiencing as they process attachment wounds. In Somatic Experiencing, the diagrams can help clients recognize when they’re moving through healthy pendulation versus getting stuck in hyperarousal or hypoarousal. Lifespan Integration practitioners can use these trajectories to assess progress as clients move through their timelines, noticing how emotional patterns shift with repeated integration.

These diagrams also serve as valuable tools for explaining treatment goals to clients and their support systems. Family members often struggle to understand why their loved one cannot simply “get over” emotional pain. Showing them the different attachment trajectories helps them appreciate the neurobiological reality of these patterns and the patience required for change.

Contemporary Somatic Approaches to Attachment Healing

The recognition that attachment patterns are somatically encoded has led to the development of body-based therapeutic approaches that work directly with these embodied patterns. Four prominent modalities—Brainspotting, Somatic Experiencing, Lifespan Integration, and Emotional Transformation Therapy—offer unique yet complementary approaches to detecting and resolving attachment trauma stored in the body.

Brainspotting

Overview

Developed by David Grand in 2003, Brainspotting identifies and utilizes the connection between eye position and emotional activation. The approach is based on the principle that “where you look affects how you feel,” using specific eye positions to access and process subcortical brain regions where trauma and attachment wounds are stored.

Attachment Applications

Brainspotting is particularly effective for attachment work because:

- It accesses implicit, pre-verbal attachment experiences without requiring explicit memories

- The dual attunement process (neurobiological and relational) directly addresses attachment needs

- It helps develop “internal secure attachment” through the co-regulation experience with the therapist

- The approach respects the client’s innate wisdom and self-directed healing capacity

Key Mechanisms

- Focused activation: Identifying “brainspots” that correlate with attachment-related activation

- Dual attunement: Simultaneous attention to neurobiological and relational processes

- Subcortical processing: Accessing deep brain structures involved in attachment

- Resource development: Building positive somatic states as anchors for security

Somatic Experiencing (SE)

Overview

Created by Peter Levine based on observations of how animals naturally discharge traumatic stress, Somatic Experiencing focuses on completing interrupted defensive responses and releasing trapped survival energy. SE recognizes that trauma symptoms result from dysregulation in the autonomic nervous system rather than the event itself.

Attachment Applications

SE addresses attachment through:

- Recognition that early attachment trauma creates specific patterns of nervous system dysregulation

- Focus on building capacity for co-regulation and self-regulation

- Attention to how attachment ruptures manifest as incomplete defensive responses

- Integration of resource-building to create somatic experiences of safety

Key Mechanisms

- Titration: Working with small amounts of activation to prevent overwhelming

- Pendulation: Moving between states of activation and calm

- Completion of thwarted responses: Allowing the body to complete interrupted defensive movements

- Resource building: Developing somatic anchors for safety and connection

Lifespan Integration (LI)

Overview

Developed by Peggy Pace in 2002, Lifespan Integration uses repetitions of a visual timeline of memories to promote neural integration across the lifespan. LI specifically addresses how early attachment experiences create fragmentation in the self-system and uses the innate healing capacity of the brain to create more coherent self-organization.

Attachment Applications

LI directly targets attachment repair through:

- Protocols specifically designed for different developmental stages and attachment wounds

- Use of imaginal “re-parenting” to provide missing attachment experiences

- Integration of fragmented self-states resulting from early attachment trauma

- Building coherent autobiographical narrative, a hallmark of secure attachment

Key Mechanisms

- Timeline repetitions: Creating proof of survival and time passage at a deep neural level

- Neural integration: Connecting isolated neural networks across developmental stages

- Right-brain to right-brain connection: Replicating early attachment dynamics in the therapeutic relationship

- State shifts: Facilitating movement through multiple self-states toward integration

Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT)

Overview

Developed by Dr. Steven Vazquez, Emotional Transformation Therapy represents a unique synthesis of attachment-based psychotherapy with innovative visual brain stimulation techniques. Vazquez explicitly acknowledges the influence of attachment theory on his work, describing ETT as an “attachment-based interpersonal approach” that recognizes how early attachment experiences create patterns requiring intervention at multiple levels. ETT uses four main components including psychotherapy, light therapy, eye movement, and brainwave entrainment/disentrainment to access and transform deeply held attachment patterns.

Attachment Applications

ETT specifically addresses attachment wounds through several mechanisms. The approach recognizes that attachment trauma often exists below the level of conscious awareness and uses precise wavelengths of light and color to access subcortical brain regions where these experiences are stored. The visual brain stimulation amplifies the therapeutic relationship, creating conditions for rapid transformation of attachment-related distress. Vazquez has documented how ETT can relieve emotional symptoms in seconds and create lasting change in attachment patterns that traditional talk therapy might take months or years to address.

Key Mechanisms

The core mechanisms of ETT include the use of maximally saturated spectral charts of colors for immediate diagnostic information about emotional states, an original form of directed eye movement that facilitates relief of emotional distress within minutes, peripheral eye stimulation techniques, and the emission of precise wavelengths of light into the client’s eyes during verbal processing. This multi-modal approach dramatically amplifies the effect of the therapeutic relationship and creates profound changes in the brain, as documented by pre and post brain scans. ETT’s emphasis on the visual system reflects an understanding that attachment experiences involve multiple sensory and processing systems beyond verbal cognition.

Integration of Approaches: Common Themes and Mechanisms

Despite their different origins and techniques, these four somatic approaches share several key features that make them effective for attachment healing:

1. Bottom-Up Processing

All four approaches work from the body up to cognition, recognizing that attachment patterns are primarily encoded in subcortical, implicit systems that cannot be accessed through top-down, verbal interventions alone.

2. Attention to the Window of Tolerance

Each modality carefully tracks and works within the client’s capacity to tolerate activation without becoming overwhelmed or dissociated, recognizing that healing happens within an optimal zone of arousal.

3. Emphasis on Safety and Co-Regulation

The therapeutic relationship serves as a secure base, with the therapist’s regulated nervous system providing co-regulation that was missing in early attachment relationships.

4. Integration Rather Than Catharsis

Rather than simply releasing emotions, these approaches focus on integrating fragmented aspects of experience into a more coherent whole.

5. Respect for the Body’s Wisdom

Each approach trusts the innate capacity of the body-mind system to heal when provided with the right conditions and support.

Clinical Implications and Applications

Assessment Considerations

When working with attachment from a somatic perspective, clinicians should assess patterns of muscle tension and holding, breathing patterns and restrictions, capacity for co-regulation in the therapeutic relationship, ability to track and tolerate bodily sensations, defensive movement patterns and gestures, and signs of autonomic dysregulation. Understanding the specific attachment subcategories identified by both Main and Brisch allows for more precise assessment and intervention planning.

Treatment Planning and Attachment-Specific Interventions

Effective somatic attachment therapy requires establishing safety and creating a secure therapeutic container, building resources and developing somatic anchors for positive states, gradual exploration by slowly approaching attachment wounds with titration, integration work to help new patterns stabilize in the nervous system, and relational repair using the therapeutic relationship as a corrective experience.

For secure attachment clients, therapy progresses more smoothly as they can utilize the therapeutic relationship effectively. These clients respond well to most interventions and can move through emotional arcs to completion. The therapist should be prepared for these clients to respond to counseling better than most and not have false doubt about their responses.

For avoidant attachment patterns, including the subcategories identified by Brisch, therapeutic responses must avoid pressuring disclosure of emotions which will increase avoidance. The pace should be slowed, with the therapist empathizing with any marginal hint of emotional distress and gently refocusing dialogue on the client’s emotions. For psychosomatic presentations, frequently monitoring bodily experiences and helping clients connect emotions with bodily sensations is essential.

For anxious-ambivalent patterns and their subcategories, interventions include interrupting verbal onslaughts of multiple emotions and breaking them down one at a time, empathetic attunement to each emotion, exhibiting and teaching good interpersonal boundaries, and teaching self-soothing. For inhibited attachment, kind and gentle empathy is particularly valuable, with encouragement of even rambling, and praise when emotions like anger emerge.

For disorganized attachment, optimal responses include interrupting chaotic verbal expression and encouraging clarity, slowing down the process to attune to each emotion, asking for completion of unfinished sentences, and being stable, consistent, and reliable. The therapist must be prepared for sudden shifts in the client’s state and maintain their own regulation throughout.

For aggressive attachment patterns, therapists should initially match the client’s intensity and pace to prevent domination, not allow ongoing venting, refocus anger to underlying contributing issues, distract and redirect instead of directly confronting, and validate more vulnerable emotions.

For role reversal attachment, maintaining appropriate interpersonal boundaries is crucial, prohibiting the client from taking care of the therapist, redirecting their focus from others to their own inner experiences, and reinforcing their value and emotions.

For those with no signs of attachment, therapy requires expecting slow bonding, being aware that false or superficial bonding is possible, challenging lack of authenticity while being a good role model, and being appropriately cautious while pursuing appropriate intimate contact.

Karl Heinz Brisch’s Clinical Contributions and Therapeutic Approach

Theoretical Framework and Clinical Philosophy

Karl Heinz Brisch, a German child and adolescent psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and attachment researcher, has made substantial contributions to the clinical application of attachment theory across the lifespan. His work bridges psychoanalytic tradition with contemporary attachment research, creating a comprehensive framework for understanding and treating attachment disorders from pregnancy through old age. Brisch views attachment as a “fundamental human motivation” that is always present and operating in the therapeutic relationship, regardless of the presenting problem or diagnostic category.

Brisch’s approach is characterized by several key principles. First, he maintains that attachment pathology is as important as psychodynamic theory in understanding and treating psychological disorders. Second, he emphasizes the transgenerational transmission of attachment patterns and the importance of early intervention. Third, he advocates for a flexible, individualized approach that adapts to the specific attachment needs of each client while maintaining theoretical rigor. His work demonstrates how attachment issues manifest differently across developmental stages and how therapeutic interventions must be tailored accordingly.

Clinical Assessment and Diagnostic Approach

Brisch’s diagnostic approach extends beyond the DSM criteria for Reactive Attachment Disorder to encompass a broader spectrum of attachment-related difficulties. He developed a comprehensive assessment framework that examines attachment patterns across multiple domains including the quality of early caregiving experiences, current relational patterns and their somatic manifestations, transgenerational attachment patterns within families, cultural and contextual factors influencing attachment, and the interplay between attachment disturbances and other psychological symptoms.

His assessment process involves careful observation of both verbal and non-verbal communication, attention to somatic manifestations of attachment patterns, and consideration of the client’s entire relational history. Brisch emphasizes that attachment disturbances often underlie various presenting problems including psychosomatic symptoms, school difficulties, behavioral problems, and relationship issues. His diagnostic formulations integrate attachment theory with psychodynamic understanding, creating rich clinical pictures that guide intervention.

Therapeutic Techniques and Interventions

Brisch’s therapeutic approach combines psychoanalytic techniques with attachment-based interventions, creating a unique synthesis that addresses both the unconscious dynamics and the attachment system. His treatment methods include several key components. The therapeutic relationship serves as a new attachment experience, with the therapist providing the consistent, attuned responsiveness that may have been missing in early relationships. Brisch emphasizes the importance of the therapist’s own attachment security and capacity for mentalization in facilitating client change.

For work with children and families, Brisch developed specific techniques that address attachment at the dyadic level. These include video feedback interventions where parents observe their interactions with their children, helping them recognize patterns and develop more attuned responses. He also uses play therapy techniques that specifically target attachment themes, allowing children to work through attachment-related conflicts in a safe, symbolic space.

With adults, Brisch’s approach involves helping clients recognize how their early attachment experiences continue to influence current relationships and symptoms. He uses a combination of interpretive work, somatic awareness, and relational experiences within the therapy to facilitate change. His case examples demonstrate how seemingly unrelated symptoms often have attachment origins, and how addressing these underlying attachment issues can lead to symptom resolution.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources – Mary Main

Main, M. (1973). Exploration and play in ten-month-old infants raised in an institution. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 12(1), 44-78.

Main, M. (1981). Avoidance in the service of attachment: A working paper. In K. Immelmann, G. Barlow, L. Petrinovich, & M. Main (Eds.), Behavioral development: The Bielefeld interdisciplinary project (pp. 651-693). Cambridge University Press.

Main, M. (1990). Cross-cultural studies of attachment organization: Recent studies, changing methodologies, and the concept of conditional strategies. Human Development, 33(1), 48-61.

Main, M. (1991). Metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive monitoring, and singular (coherent) vs. multiple (incoherent) model of attachment: Findings and directions for future research. In C. M. Parkes, J. Stevenson-Hinde, & P. Marris (Eds.), Attachment across the life cycle (pp. 127-159). Tavistock/Routledge.

Main, M. (1995). Recent studies in attachment: Overview, with selected implications for clinical work. In S. Goldberg, R. Muir, & J. Kerr (Eds.), Attachment theory: Social, developmental, and clinical perspectives (pp. 407-474). Analytic Press.

Main, M. (1996). Introduction to the special section on attachment and psychopathology: 2. Overview of the field of attachment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 237-243.

Main, M. (2000). The organized categories of infant, child, and adult attachment: Flexible vs. inflexible attention under attachment-related stress. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 48(4), 1055-1096.

Main, M., & George, C. (1985). Responses of abused and disadvantaged toddlers to distress in agemates: A study in the day care setting. Developmental Psychology, 21(3), 407-412.

Main, M., & Goldwyn, R. (1984). Predicting rejection of her infant from mother’s representation of her own experience: Implications for the abused-abusing intergenerational cycle. Child Abuse & Neglect, 8(2), 203-217.

Main, M., & Goldwyn, R. (1998). Adult attachment scoring and classification system. Unpublished classification manual, Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley.

Main, M., & Hesse, E. (1990). Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 161-182). University of Chicago Press.

Main, M., & Hesse, E. (1992). Disorganized/disoriented infant behavior in the Strange Situation, lapses in the monitoring of reasoning and discourse during the parent’s Adult Attachment Interview, and dissociative states. In M. Ammaniti & D. Stern (Eds.), Attachment and psychoanalysis (pp. 86-140). Gius, Laterza & Figli.

Main, M., & Hesse, E. (2006). Frightening, frightened, dissociated, or disorganized behavior on the part of the caregiver: A coding system for frightening parent-infant interactions. In M. C. Moran, D. Pederson, D. Peitsch, & C. Krupka (Eds.), Unresolved attachment, dissociation, and disorganization (pp. 203-212). Jason Aronson.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1-2), 66-104.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95-124). Ablex.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 121-160). University of Chicago Press.

Main, M., & Weston, D. R. (1981). The quality of the toddler’s relationship to mother and to father: Related to conflict behavior and the readiness to establish new relationships. Child Development, 52(3), 932-940.

Primary Sources – Karl Heinz Brisch

Brisch, K. H. (1999). Treating attachment disorders: From theory to therapy. Guilford Press.

Brisch, K. H. (2002). Disorders of attachment: From theory to treatment. W. W. Norton.

Brisch, K. H. (2004). Bindungsstörungen: Von der Bindungstheorie zur Therapie [Attachment disorders: From attachment theory to therapy]. Klett-Cotta.

Brisch, K. H. (2009). Attachment disorders in children and adolescents. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie, 58(4), 244-270.

Brisch, K. H. (2011). SAFE – Sichere Ausbildung für Eltern: Sichere Bindung zwischen Eltern und Kind [SAFE – Secure training for parents: Secure attachment between parents and child]. Klett-Cotta.

Brisch, K. H. (2012). Attachment and early prevention. Attachment & Human Development, 14(3), 233-242.

Brisch, K. H. (2014). Attachment in psychotherapy. W. W. Norton.

Brisch, K. H. (2017). SAFE – Sichere Ausbildung für Eltern: Sichere Bindung zwischen Eltern und Kind (2nd ed.). Klett-Cotta.

Brisch, K. H. (2018). Attachment-based prevention and intervention programs. Attachment & Human Development, 20(2), 133-154.

Brisch, K. H., & Hellbrügge, T. (Eds.). (2003). Bindung und Trauma: Risiken und Schutzfaktoren für die Entwicklung von Kindern [Attachment and trauma: Risk and protective factors for child development]. Klett-Cotta.

Brisch, K. H., & Hellbrügge, T. (Eds.). (2006). Kinder ohne Bindung: Deprivation, Adoption und Psychotherapie [Children without attachment: Deprivation, adoption and psychotherapy]. Klett-Cotta.

Brisch, K. H., & Hellbrügge, T. (Eds.). (2010). Wege zu sicherer Bindung in Familie und Gesellschaft: Prävention, Begleitung, Beratung und Psychotherapie [Paths to secure attachment in family and society: Prevention, support, counseling and psychotherapy]. Klett-Cotta.

Secondary Sources – Attachment Theory

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1967). Infancy in Uganda: Infant care and the growth of love. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1973). The development of infant-mother attachment. In B. M. Caldwell & H. N. Ricciuti (Eds.), Review of child development research (Vol. 3, pp. 1-94). University of Chicago Press.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46(4), 333-341.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1985). Adult Attachment Interview. Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Berkeley.

Grossmann, K. E., Grossmann, K., & Waters, E. (Eds.). (2005). Attachment from infancy to adulthood: The major longitudinal studies. Guilford Press.

Hesse, E. (2016). The Adult Attachment Interview: Protocol, method of analysis, and selected empirical studies: 1985-2015. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 553-597). Guilford Press.

Lyons-Ruth, K., & Jacobvitz, D. (2016). Attachment disorganization from infancy to adulthood: Neurobiological correlates, parenting contexts, and pathways to disorder. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 667-695). Guilford Press.

Rutter, M. (1995). Clinical implications of attachment concepts: Retrospect and prospect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36(4), 549-571.

Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 7(4), 349-367.

van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1995). Adult attachment representations, parental responsiveness, and infant attachment: A meta-analysis on the predictive validity of the Adult Attachment Interview. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 387-403.

van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (1996). Attachment representations in mothers, fathers, adolescents, and clinical groups: A meta-analytic search for normative data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(1), 8-21.

van IJzendoorn, M. H., Schuengel, C., & Bakermans-Kranenberg, M. J. (1999). Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology, 11(2), 225-249.

Influenced Researchers and Clinicians

Cozolino, L. (2014). The neuroscience of human relationships: Attachment and the developing social brain (2nd ed.). W. W. Norton.

Cozolino, L. (2017). The neuroscience of psychotherapy: Healing the social brain (3rd ed.). W. W. Norton.

Fosha, D. (2000). The transforming power of affect: A model for accelerated change. Basic Books.

Fosha, D. (2008). Transformance, recognition of self by self, and effective action. In K. J. Schneider (Ed.), Existential-integrative psychotherapy: Guideposts to the core of practice (pp. 290-320). Routledge.

Fosha, D., Siegel, D. J., & Solomon, M. F. (Eds.). (2009). The healing power of emotion: Affective neuroscience, development & clinical practice. W. W. Norton.

Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the tiger: Healing trauma. North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

Liotti, G. (2004). Trauma, dissociation, and disorganized attachment: Three strands of a single braid. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41(4), 472-486.

Liotti, G. (2006). A model of dissociation based on attachment theory and research. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(4), 55-73.

Ogden, P. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. W. W. Norton.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. W. W. Norton.

Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment. W. W. Norton.

Schore, A. N. (1994). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: The neurobiology of emotional development. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schore, A. N. (2003a). Affect dysregulation and disorders of the self. W. W. Norton.

Schore, A. N. (2003b). Affect regulation and the repair of the self. W. W. Norton.

Schore, A. N. (2012). The science of the art of psychotherapy. W. W. Norton.

Schore, A. N. (2016). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: The neurobiology of emotional development (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Schore, A. N. (2019). Right brain psychotherapy. W. W. Norton.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J. (2007). The mindful brain: Reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. W. W. Norton.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J. (2020). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J., & Hartzell, M. (2003). Parenting from the inside out: How a deeper self-understanding can help you raise children who thrive. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin.

Solomon, M. F., & Siegel, D. J. (Eds.). (2003). Healing trauma: Attachment, mind, body, and brain. W. W. Norton.

Vazquez, S. R. (2012). Emotional transformation therapy: An interactive ecological psychotherapy. Jason Aronson.

Vazquez, S. R. (2013). The neurobiology of attachment-based psychotherapy: Understanding the healing power of emotional transformation therapy. International Journal of Healing and Caring, 13(2), 1-15.

Somatic Therapy Approaches

Corrigan, F. M., & Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: Recruiting the midbrain for accessing and healing sensorimotor memories of traumatic activation. Medical Hypotheses, 80(6), 759-766.

Dana, D. (2018). The polyvagal theory in therapy: Engaging the rhythm of regulation. W. W. Norton.

Dana, D. (2020). Polyvagal exercises for safety and connection: 50 client-centered practices. W. W. Norton.

Gendlin, E. T. (1996). Focusing-oriented psychotherapy: A manual of the experiential method. Guilford Press.

Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: The revolutionary new therapy for rapid and effective change. Sounds True.

Grand, D. (2016). This is your brain on sports: The science of underdogs, the value of rivalry, and what we can learn from the T-shirt cannon. Random House.

Heller, L., & LaPierre, A. (2012). Healing developmental trauma: How early trauma affects self-regulation, self-image, and the capacity for relationship. North Atlantic Books.

Kain, K. L., & Terrell, S. J. (2018). Nurturing resilience: Helping clients move forward from developmental trauma. North Atlantic Books.

Kurtz, R. (1990). Body-centered psychotherapy: The Hakomi method. LifeRhythm.

Levine, P. A. (2008). Healing trauma: A pioneering program for restoring the wisdom of your body. Sounds True.

Levine, P. A., & Frederick, A. (1997). Waking the tiger: Healing trauma. North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P. A., & Kline, M. (2007). Trauma through a child’s eyes: Awakening the ordinary miracle of healing. North Atlantic Books.

Ogden, P. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: One method for processing traumatic memory. In U. Schnyder & M. Cloitre (Eds.), Evidence based treatments for trauma-related psychological disorders (pp. 417-440). Springer.

Pace, P. (2003). Lifespan integration: Connecting ego states through time. Lifespan Integration.

Pace, P. (2012). Lifespan integration: The theory and application. Lifespan Integration.

Payne, P., Levine, P. A., & Crane-Godreau, M. A. (2015). Somatic experiencing: Using interoception and proprioception as core elements of trauma therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 93.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton.

Rothschild, B. (2000). The body remembers: The psychophysiology of trauma and trauma treatment. W. W. Norton.

Scaer, R. C. (2005). The trauma spectrum: Hidden wounds and human resiliency. W. W. Norton.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). Mindsight: The new science of personal transformation. Bantam.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Research Studies and Meta-Analyses

Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2009). The first 10,000 Adult Attachment Interviews: Distributions of adult attachment representations in clinical and non-clinical groups. Attachment & Human Development, 11(3), 223-263.

Benoit, D., & Parker, K. C. (1994). Stability and transmission of attachment across three generations. Child Development, 65(5), 1444-1456.

Carlson, E. A. (1998). A prospective longitudinal study of attachment disorganization/disorientation. Child Development, 69(4), 1107-1128.

Cyr, C., Euser, E. M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 87-108.

Duschinsky, R. (2020). Cornerstones of attachment research. Oxford University Press.

Fearon, R. P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Lapsley, A. M., & Roisman, G. I. (2010). The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children’s externalizing behavior: A meta-analytic study. Child Development, 81(2), 435-456.

George, C., & Solomon, J. (2008). The caregiving system: A behavioral systems approach to parenting. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 833-856). Guilford Press.

Groh, A. M., Roisman, G. I., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Fearon, R. P. (2012). The significance of attachment security for children’s social competence with peers: A meta-analytic study. Attachment & Human Development, 14(2), 79-102.

Madigan, S., Atkinson, L., Laurin, K., & Benoit, D. (2013). Attachment and internalizing behavior in early childhood: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 672-689.

Verhage, M. L., Schuengel, C., Madigan, S., Fearon, R. M. P., Oosterman, M., Cassibba, R., … & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). Narrowing the transmission gap: A synthesis of three decades of research on intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 142(4), 337-366.

Weinfield, N. S., Sroufe, L. A., Egeland, B., & Carlson, E. A. (2008). Individual differences in infant-caregiver attachment: Conceptual and empirical aspects of security. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 78-101). Guilford Press.

0 Comments