The Dark Mirror of the Soul

In the humid, kudzu-draped landscapes of the American South, a literary tradition emerged that would plumb the depths of the human psyche like few others. Southern Gothic literature, with its haunting tales of decay, madness, and the supernatural, serves as a powerful lens through which we can examine the complexities of the human mind. From the perspective of Jungian psychology, these stories offer rich territory for exploring concepts like the shadow, collective unconscious, and the journey towards individuation.

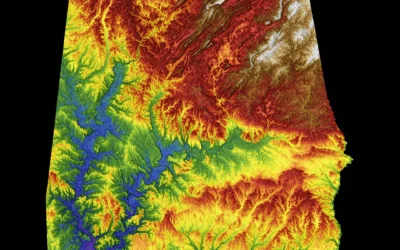

Birmingham, Alabama, nestled in the heart of the South, has its own connections to this literary tradition. While not as widely recognized as other Southern literary hubs, Birmingham’s history of racial tension, industrial boom and bust, and the lingering echoes of the Civil War provide fertile ground for Gothic themes. The city’s Sloss Furnaces, now a haunting industrial museum, could easily serve as a backdrop for a Southern Gothic tale, its rusted structures looming like the decaying mansions so common in the genre.

To truly understand the psychological power of Southern Gothic literature, we must first turn to two of its most prominent practitioners: Truman Capote and Flannery O’Connor. Both authors, though different in style and background, share a fascination with the darker aspects of human nature and the hidden currents that shape our lives.

Truman Capote

Truman Capote, born in New Orleans but spending much of his childhood in Alabama, crafted stories that often dealt with themes of isolation and the struggle for identity. His novella “Other Voices, Other Rooms” is a prime example of how Southern Gothic can serve as a vehicle for exploring Jungian concepts. The protagonist, Joel Knox, embarks on a journey to find his father, which can be read as a metaphor for the quest to understand one’s own psyche. The strange and often grotesque characters Joel encounters along the way can be seen as manifestations of different aspects of the psyche, particularly the shadow.

In Jungian psychology, the shadow represents the aspects of ourselves that we repress or deny. It’s the dark mirror of our conscious self, containing all the traits and impulses we’d rather not acknowledge. Southern Gothic literature excels at bringing these shadow elements to the forefront. Capote’s decrepit Skully’s Landing, with its reclusive and mysterious inhabitants, serves as a physical manifestation of the shadow realm. Joel’s journey through this landscape is a journey into his own unconscious, confronting the parts of himself he’s yet to integrate.

Flannery O’Connor

Flannery O’Connor, perhaps the most renowned Southern Gothic author, takes this exploration of the shadow to even greater extremes. Her stories are populated by characters who are physically or mentally grotesque, often serving as exaggerated embodiments of human flaws and failings. In “Good Country People,” the character of Hulga, with her wooden leg and Ph.D. in philosophy, represents the intellect divorced from the body and spirit. Her encounter with the Bible salesman who steals her prosthetic leg can be seen as a brutal confrontation with the shadow, forcing Hulga to recognize the limitations of her purely intellectual approach to life.

O’Connor’s work is particularly rich in mystical and transcendental elements, often culminating in moments of harsh grace that force characters to confront their true selves. In “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” the Misfit serves as a dark agent of transformation, his violent actions paradoxically leading to the grandmother’s moment of spiritual clarity. This aligns with Jung’s concept of the transcendent function, where opposing elements of the psyche are brought into dialogue, potentially leading to a higher state of consciousness.

Other Southern Gothic authors have similarly explored these Jungian themes. William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County serves as a collective unconscious for the South, its tangled family histories and buried secrets representing the psychological legacy we all inherit. Carson McCullers’ exploration of alienation and the search for connection in works like “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter” speaks to the Jungian concept of individuation, the process of becoming one’s true self.

Even contemporary Southern Gothic works continue this tradition. Birmingham’s own Gin Phillips, in her novel “Come In and Cover Me,” uses ghostly visitations as a means of exploring memory, grief, and self-discovery. The protagonist’s archaeological work serves as a metaphor for digging into the layers of the psyche, unearthing buried truths and confronting the shadows of the past.

The Archetypal in Southern Gothic

The power of Southern Gothic literature lies in its ability to externalize internal psychological states. The decaying mansions, overgrown gardens, and oppressive heat serve as physical manifestations of psychological conditions. This externalization allows readers to confront difficult truths about themselves in a way that might be too threatening if approached directly.

The mystical elements common in Southern Gothic literature align well with Jung’s interest in the numinous and transcendent aspects of the psyche. The genre’s frequent use of religious imagery and supernatural occurrences speaks to the human need for meaning beyond the material world. This can be particularly relevant in a place like Birmingham, where religious faith remains a significant part of the cultural landscape.

The concept of the collective unconscious and inter-generational trauma is also vividly illustrated in Southern Gothic works. The genre’s preoccupation with history, particularly the lingering effects of slavery and the Civil War, speaks to the psychological burdens we inherit from our culture and ancestors. In Birmingham, a city marked by its civil rights history, this aspect of Southern Gothic resonates strongly. The shadows of the past are ever-present, influencing the present in ways both subtle and overt.

It’s worth noting that while Southern Gothic literature often deals with dark and disturbing themes, it’s not without hope. The genre’s use of humor, albeit often dark, serves as a means of confronting difficult truths. This aligns with Jung’s belief in the importance of accepting all aspects of oneself, including the shadow, as a path to wholeness.

Furthermore, the transformative journeys undertaken by many Southern Gothic protagonists mirror the process of individuation. Characters are forced to confront their shadows, integrate disparate aspects of their psyches, and emerge changed. While this process is often painful and fraught with danger, it ultimately leads to greater self-awareness and authenticity.

In conclusion, Southern Gothic literature serves as a powerful tool for exploring the depths of the human psyche. Its vivid externalization of internal states, its confrontation with the shadow, and its exploration of mystical and transcendent experiences all align closely with Jungian psychology. For readers and therapy clients alike, these stories offer a mirror in which to see our own psychological struggles and potential for growth.

As we walk the streets of Birmingham, from the historic civil rights districts to the revitalized loft areas, we might consider how the city’s own history of struggle and renewal reflects the transformative journeys found in Southern Gothic literature. The genre reminds us that growth often comes through confronting our shadows, and that even in the most unlikely places – be it a decaying Southern mansion or a former industrial city – we can find the path to our true selves.

In the end, Southern Gothic literature, like Jungian psychology, invites us to embrace the fullness of human experience – the beautiful and the grotesque, the rational and the mystical, the conscious and the unconscious. It’s a tradition that continues to resonate, offering insight and catharsis to those willing to venture into its shadowy, kudzu-covered realms.

Bibliography:

1. Bloom, H. (2009). Flannery O’Connor (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views). Infobase Publishing.

2. Capote, T. (1948). Other Voices, Other Rooms. Random House.

3. Carpenter, B. (2013). “Splendid Failure”: Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Humanities, 2(4), 756-782.

4. Ciuba, G. M. (2007). Desire, Violence & Divinity in Modern Southern Fiction: Katherine Anne Porter, Flannery O’Connor, Cormac McCarthy. LSU Press.

5. Faulkner, W. (1929). The Sound and the Fury. Jonathan Cape & Harrison Smith.

6. Fowler, D. (1997). Faulkner: The Return of the Repressed. University of Virginia Press.

7. Gentry, M. B. (1986). Flannery O’Connor’s Religion of the Grotesque. Univ. Press of Mississippi.

8. Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and His Symbols. Doubleday.

9. Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological Types (Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 6). Princeton University Press.

10. McCullers, C. (1940). The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. Houghton Mifflin.

11. O’Connor, F. (1955). A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

12. Phillips, G. (2012). Come In and Cover Me. Riverhead Books.

13. Proehl, K. B. (2019). Queer Gothic Literature: An Annotated Bibliography. McFarland.

14. Rubin, L. D. (1985). The History of Southern Literature. LSU Press.

15. Skei, H. H. (1999). Reading Faulkner’s Best Short Stories. University of South Carolina Press.

16. Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court.

17. Todorov, T. (1975). The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Cornell University Press.

18. Yaeger, P. (2000). Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women’s Writing, 1930-1990. University of Chicago Press.

19. Young-Eisendrath, P., & Dawson, T. (Eds.). (2008). The Cambridge Companion to Jung. Cambridge University Press.

20. Zimmerman, B. (1999). The Safe Sea of Women: Lesbian Fiction 1969-1989. Beacon Press.

Birmingham Arts and Culture

0 Comments