Hans J. Wegner: Archetypes of Danish Chair Design

The Valet Chair. Hang your suit, hang your shirts and shoes, get dressed, sit down.

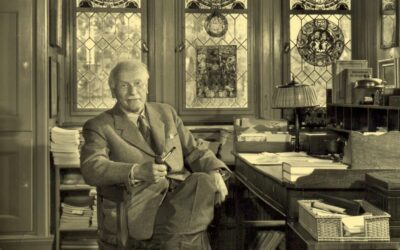

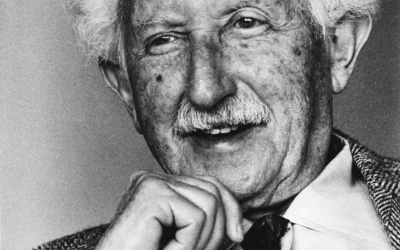

Hans J. Wegner (1914-2007) was a pioneering Danish furniture designer whose work helped define the aesthetic of mid-century modern design. Over a prolific career spanning nearly seven decades, Wegner crafted a stunning array of chairs that married the sleek functionality of modernism with the warmth and organic sensibility of natural materials. His designs, at once timeless and utterly original, gave expression to the deepest principles of form and craftsmanship. Distilling the essence of a chair to its purest elements, Wegner created archetypal seats that continue to inspire designers, enchant users, and shape our collective imagination of what furniture can be.

Who was Hans Jørgensen Wegner?

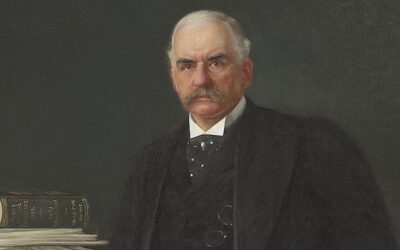

Hans Jørgensen Wegner was born on April 2, 1914, in Tønder, a small town in southern Denmark. As a young man, Wegner apprenticed as a cabinetmaker before attending the School of Arts and Crafts in Copenhagen. After completing his studies in 1938, he began working as an assistant to architect and furniture designer Arne Jacobsen.

In 1943, Wegner established his own design studio in Aarhus, Denmark. He quickly gained recognition for his innovative chair designs, which combined traditional craftsmanship with a modernist sensibility. Over the course of his career, Wegner designed more than 500 chairs, many of which have become icons of 20th-century design.

Wegner’s work was characterized by a deep respect for wood and a mastery of joinery techniques. He often spent months or even years perfecting a single design, making countless prototypes until he achieved the perfect balance of form and function. His chairs were not only beautiful but also incredibly comfortable, thanks to his keen understanding of ergonomics and the human body.

In addition to his work as a designer, Wegner was also an influential teacher and mentor. From 1977 to 1979, he served as Rector of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, where he inspired a new generation of Danish designers.

Wegner continued to design furniture well into his eighties, always striving for simplicity, functionality, and beauty. He passed away on January 26, 2007, at the age of 92, leaving behind an unparalleled legacy in the world of furniture design.

Key Ideas and Contributions

Organic Functionalism

At the heart of Wegner’s design philosophy was a commitment to what he called “organic functionalism.” For Wegner, a chair was not merely a machine for sitting but a dynamic sculptural presence that should engage the body, mind, and spirit of the user. His chairs, while rigorously constructed and exquisitely proportioned, eschew the cold industrial look of much modernist furniture in favor of an inviting, almost animate warmth.

Wegner achieved this vitality through his deep attunement to the organic properties of his materials, primarily wood. He had an uncanny ability to “listen” to the wood, to discern the inner logic of the grain and let it guide his designs. His forms often seem to grow organically from the material, as if they were latent possibilities coaxed into being by the craftsman’s hand.

This organic sensibility is evident in the gentle curves and flowing lines of Wegner’s chairs, which often mirror natural motifs like leaves, branches, or bones. There is a sense of growth and movement in his designs, a feeling that they have been shaped by the same evolutionary forces that mold living creatures. At the same time, Wegner’s chairs are marvels of structural integrity, with each element honed to perfection and joined seamlessly to the whole.

Archetypal Forms

Wegner’s genius lay in his ability to distill the essence of a chair into archetypal forms that seem at once freshly original and utterly timeless. He had an uncanny knack for creating designs that, in his own words, “summarize all of the chairs that have ever been and all of the chairs that will ever be.”

This quest for archetypal purity is evident in Wegner’s most iconic designs, such as the Round Chair (1949), the Wishbone Chair (1950), and the Ox Chair (1960). Each of these masterpieces seems to capture the platonic ideal of a chair, the core structure and gesture that defines the very concept of sitting.

The Round Chair, for example, with its simple, sweeping curves and tapered legs, evokes the primordial grace of a tree or a human body. It is a study in poise and balance, a visual haiku that says everything there is to say about the art of repose. Similarly, the Wishbone Chair, with its signature Y-shaped back, marries the sturdiness of a workhorse with the lightness of a dancer. It is at once earthy and ethereal, a seat that seems to emerge organically from the floor and float effortlessly in space.

In distilling his chairs to their archetypal essence, Wegner tapped into something universal and deeply resonant in the human psyche. His designs seem to awaken a primal recognition, a sense of having encountered these forms before in some ancestral memory. They connect us to the long lineage of human making and dwelling, to the timeless rituals of crafting, sitting, and communing that have shaped our species since the dawn of time.

Wegner’s Most Iconic Designs

The Wishbone Chair (1949)

Also known as the Y Chair, this design is perhaps Wegner’s most recognizable and commercially successful creation. Its distinctive Y-shaped back support and woven seat combine comfort with a light, airy aesthetic.

The Round Chair (1949)

Often simply called “The Chair,” this design gained international fame when it was used in the televised 1960 U.S. presidential debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Its elegant simplicity and perfect proportions make it a quintessential example of Danish modern design.

The Papa Bear Chair (1951)

This oversized armchair, with its enveloping form and “bear hug” armrests, exemplifies Wegner’s ability to combine comfort with sculptural presence.

The Ox Chair (1960)

With its distinctive headrest reminiscent of ox horns, this chair showcases Wegner’s playful approach to design and his ability to create statement pieces that are also functional.

Collaboration with Manufacturers

Wegner’s long-standing collaboration with Danish furniture manufacturer Carl Hansen & Søn was crucial to bringing his designs to a wider audience. This partnership, which began in the 1940s, allowed Wegner to maintain high standards of craftsmanship while producing his chairs on a larger scale.

Other important manufacturing partnerships included PP Møbler and Johannes Hansen, both of which worked closely with Wegner to realize his designs with the utmost attention to detail and quality.

The Chair as Portrait

For Wegner, every chair was a kind of portrait – a study in the endless variations of human posture and personality. He approached each design as a unique challenge to create a seat that would not only support the body but express some essential quality of the sitter.

This anthropomorphic sensibility is evident in the way Wegner’s chairs seem to embody different character types and moods. The Papa Bear Chair (1951), for example, with its massive, enveloping frame, exudes a sense of paternal comfort and security. The Ox Chair, with its muscular, hunched form and horn-like armrests, suggests a brooding, almost primal energy. And the Peacock Chair (1947), with its fan-like back and delicate spindles, evokes the showy elegance of its avian namesake.

In designing chairs that capture these archetypal human qualities, Wegner created more than just functional objects. He gave form to the intangible textures of our inner lives – the yearning for comfort, the need for strength, the delight in beauty. His chairs are not merely inanimate props but active partners in the drama of human existence. They shape the way we inhabit space and time, the way we feel and relate to the world around us.

This empathic dimension of Wegner’s work reflects his deep humanism, his belief in design as a medium for enhancing and celebrating the richness of embodied life. For Wegner, the chair was the ultimate test of a designer’s ability to marry form and function, aesthetics and ergonomics, in service of human flourishing. Each of his designs is a love letter to the art of sitting, a tribute to the endless poetry of the body at rest.

Craftsmanship as Spiritual Practice

Underlying Wegner’s design philosophy was a profound reverence for the art and craft of making. He saw woodworking not merely as a means to an end but as a spiritual practice, a way of attuning oneself to the inherent wisdom of natural materials and the age-old rhythms of handcraft.

Wegner’s process was one of deep dialogue with his medium. He would spend hours studying a piece of wood, running his hands over the grain, feeling for the hidden potential within. His designs emerged not from abstract calculations but from a kind of tactile intuition, a felt sense of what the wood “wanted to be.”

This intimacy with his materials was reflected in Wegner’s legendary attention to detail. Every joint, every curve, every plane of his chairs was meticulously considered and refined, often through countless iterations. Wegner was known to spend months, even years, perfecting a single design, tweaking angles and proportions until he achieved the perfect balance of strength, comfort, and visual harmony.

For Wegner, this obsessive pursuit of perfection was not merely a technical exercise but a spiritual discipline. It was a way of honoring the inherent dignity of his materials, of giving voice to the mute poetry of wood. In lavishing such care and attention on each piece, Wegner was practicing a kind of devotional craftsmanship, a meditation on the sacred art of making.

This spiritual dimension of Wegner’s work reflects a broader ethos of mindfulness and presence that suffuses Danish design culture. In the Danish tradition, the act of making is seen not merely as a means to an end but as an end in itself, a way of cultivating a deep attunement to the here and now. By pouring himself fully into the present moment of crafting, Wegner was participating in a timeless ritual of creation, a cosmic dance of hand, heart, and material.

Democratizing Design

While Wegner’s chairs are often regarded as elite objects, coveted by collectors and enshrined in museums, his vision was fundamentally democratic. He believed that good design should be accessible to all, that the benefits of beauty and craftsmanship should be shared widely.

This egalitarian ethos was shaped by Wegner’s experiences of scarcity and hardship during World War II. As a young cabinetmaker in Copenhagen, he witnessed firsthand the deprivations of the Nazi occupation, the scarcity of materials and the desperate need for functional, affordable furniture. These experiences instilled in him a deep commitment to creating designs that were not only beautiful but also durable, efficient, and within reach of the average consumer.

Wegner’s democratic vision was embodied in his close collaboration with Danish manufacturer Carl Hansen & Søn, which produced many of his most iconic designs. By working with industrial methods and materials, Wegner was able to translate his handcrafted prototypes into mass-produced chairs that retained the warmth and integrity of the originals. His Round Chair, for example, was specifically designed for efficient factory production, with a simplified construction that could be easily replicated without compromising its sculptural grace.

In making his designs accessible to a broad public, Wegner helped to democratize the idea of good design. He showed that the values of craftsmanship, materiality, and organic form were not the exclusive preserve of the wealthy elite but could be woven into the fabric of everyday life. His chairs became staples of Danish homes and public spaces, beloved for their comfort, durability, and understated beauty.

This democratic legacy continues to inspire designers today, who look to Wegner as a model of how to marry high artistic vision with social responsibility. In an age of rampant consumerism and disposable goods, Wegner’s chairs stand as enduring testaments to the value of investing in timeless, well-made objects that enrich our daily lives. They remind us that the true measure of a design’s worth lies not in its price tag or prestige but in its capacity to serve and delight the widest possible audience.

The Enduring Relevance of Wegner’s Vision

Half a century after their creation, Wegner’s chairs continue to captivate us with their timeless grace and ingenuity. In a world of fast-paced change and digital distraction, they offer a tangible link to the enduring values of craftsmanship, materiality, and mindful presence. They remind us of the simple, profound pleasure of inhabiting a well-made object, of feeling the weight and warmth of natural wood against our bodies.

But Wegner’s legacy extends beyond the individual chairs he created. His larger vision of organic functionalism, of design attuned to the rhythms of nature and the needs of the human spirit, remains as urgent and relevant today as ever. In an age of ecological crisis and social fragmentation, Wegner’s work points the way towards a more holistic, humane approach to shaping our material world.

At the heart of this approach is a deep respect for the inherent wisdom of natural materials, a willingness to listen and adapt to the constraints and opportunities they offer. Wegner’s chairs embody this ecological sensibility, not only in their use of sustainable woods but in their organic forms and structures. They remind us that the most enduring designs are those that work with, rather than against, the flows and forces of nature.

Wegner’s work also speaks to the enduring power of archetypal forms to shape our experience of the world. His chairs tap into something deep and primal in the human psyche, awakening a sense of recognition and belonging. In a culture of constant novelty and superficial sensation, Wegner’s designs offer a grounding connection to the timeless patterns and gestures that have defined human experience across the ages.

Perhaps most importantly, Wegner’s legacy reminds us of the vital role of craftsmanship in an age of mass production and digital automation. His chairs are not merely functional objects but embodied expressions of human care, skill, and imagination. They bear the traces of the hands that made them, the countless hours of attention and devotion that went into each curve and joint.

In a world increasingly disconnected from the tangible realities of making, Wegner’s chairs invite us to reconnect with the transformative power of craftsmanship. They remind us that the objects we surround ourselves with are not merely inanimate props but active partners in shaping our sense of self and world. By investing in things that are made with love and skill, we not only enrich our immediate environment but also support a wider ecology of artisanship and sustainable production.

Ultimately, Wegner’s enduring relevance lies in his unwavering commitment to design as a humanistic practice, a way of enhancing and celebrating the richness of embodied life. His chairs are not merely beautiful objects but instruments of empathy and care, shaped to support and delight the bodies and spirits of those who use them. They embody a vision of design as a form of service, a way of attuning ourselves to the needs and desires of others.

In this sense, Wegner’s legacy offers a powerful counterpoint to the prevailing ethos of our time, with its obsessive focus on individual expression and personal branding. His work reminds us that the true measure of a designer’s worth lies not in their ability to impose a signature style but in their capacity to listen and respond to the world around them. It calls us to a more generous, empathetic understanding of design as a collaborative practice, a way of bringing forth the latent potentials of materials and people alike.

As we navigate the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, Wegner’s vision offers a compelling model for how to design with integrity, humility, and care. His chairs are not merely beautiful artifacts but embodied manifestos, calling us to a more mindful, responsible engagement with the material world. They remind us of the enduring power of archetypal forms to shape our experience, the vital role of craftsmanship in an age of mass production, and the transformative potential of design to enrich and ennoble human life.

May we heed the wisdom of these silent teachers, these humble yet profound expressions of the designer’s art. May we learn from Wegner’s example to listen more deeply to the materials and people around us, to attune ourselves to the timeless rhythms of nature and craft. And may we carry forward his vision of design as a humanistic practice, a way of shaping a world that honors the dignity and diversity of all living things.

Timeline of Wegner’s Chair Designs and Historical Context

1914: Hans J. Wegner is born in Tønder, Denmark.

1938: Wegner begins his career as a cabinetmaker’s apprentice.

1940: Denmark is occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II, leading to scarcity of materials and a need for functional, affordable furniture.

1943: Wegner designs the Chinese Chair, inspired by portraits of Danish merchants sitting in Ming chairs.

1944: Wegner establishes a joint studio with Børge Mogensen and begins designing for Carl Hansen & Søn.

1947: Wegner designs the Peacock Chair, with its distinctive fan-like back.

1949: The Round Chair (later known as “The Chair”) is designed, becoming an icon of Danish modernism. It gains international popularity after being used in the first televised U.S. presidential debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960.

1950: Wegner designs the Wishbone Chair, his most commercially successful design, which has been in continuous production since its inception.

1951: The Papa Bear Chair is introduced, with its generous proportions and embrace.

1952: The United Nations Building in New York City is completed, symbolizing the postwar internationalist spirit that helped popularize Scandinavian modernism.

1955: The U.S. magazine Interiors features Wegner’s designs, bringing international attention to Danish modern furniture.

1960: Wegner designs the Ox Chair, with its distinctive headrest shaped like ox horns.

1962: The CH07 Shell Chair is introduced, showcasing Wegner’s mastery of bent plywood techniques.

1963: Wegner receives the Lunning Prize, a prestigious award for Scandinavian designers.

1965: The Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) features an exhibition entitled “Elegant Chairs,” which includes three contributions by Wegner: the Round Chair, the Folding Chair, and the Wishbone Chair.

1969: Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin land on the moon, reflecting the technological optimism of the Space Age that influenced mid-century design.

1977 to 1979: Wegner serves as Rector of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen.

1980s-1990s: Wegner continues to design chairs, increasingly focusing on designs that feature upholstery.

1992: Wegner reissues the Ox Chair, originally designed in 1960, with an updated upholstery method.

1997: The EU Parliament building in Brussels installs over 500 of Wegner’s Ox Chairs in its Danish Parliament Office.

2000s: Wegner’s designs experience a resurgence in popularity, with many of his classic chairs being reissued and celebrated as icons of 20th-century design.

2007: Hans J. Wegner passes away at the age of 92, leaving behind a legacy of over 500 chair designs.

2014: The Design Museum Denmark hosts a major retrospective exhibition to mark the 100th anniversary of Wegner’s birth.

0 Comments