How Religious Trauma Shapes Your Adult Relationships and Self-Perception

Religious trauma is a deeply wounding experience that can have far-reaching effects on an individual’s emotional, psychological, and spiritual well-being. It is a complex phenomenon that often occurs in the context of authoritarian, fear-based religious environments that prioritize rigid doctrine over individual autonomy and critical thinking.

At its core, religious trauma represents a profound betrayal of trust. When a religious institution or leader that one has relied on for guidance, community, and meaning-making is revealed to be abusive, manipulative, or deceptive, it can shatter one’s foundational assumptions about the world and one’s place in it.

The impact of this betrayal can be particularly acute when it occurs during childhood or adolescence, when the self is still forming and the need for secure attachment is paramount. A child who is subjected to religious abuse – whether in the form of emotional manipulation, physical violence, or sexual exploitation – may internalize a profound sense of shame, guilt, and self-doubt.

The Developmental Impact of Religious Trauma

To understand the long-term effects of religious trauma, it’s helpful to consider the role of religion in human development. For many individuals, religion provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the world, one’s purpose in it, and the nature of reality itself. It offers answers to existential questions, codes of moral conduct, and rituals for marking significant life transitions.

In healthy religious environments, this framework can provide a sense of meaning, belongingness, and transcendence. It can foster the development of virtues like compassion, gratitude, and forgiveness. It can offer solace in times of suffering and a sense of continuity across generations.

However, in environments where religion is used as a means of control and manipulation, it can have a profoundly distorting effect on development. When a child is taught that they are inherently sinful, that their thoughts and feelings are untrustworthy, and that they must submit unquestioningly to authority, it undermines the very foundations of healthy self-formation.

Moreover, the child may learn to split off parts of themselves that do not conform to the rigid religious ideal. They may develop a false self that is compliant, pious, and self-denying, while their authentic self remains hidden and unexpressed. This self-fragmentation can lead to chronic feelings of emptiness, disconnection, and self-alienation.

The Relational Imprint of Religious Trauma

The impact of religious trauma extends beyond the individual psyche; it also shapes the way one relates to others. Having been betrayed by those they trusted most, survivors of religious trauma may struggle with profound relational ambivalence and insecurity.

On one hand, they may long for deep, authentic connection – for the unconditional love and acceptance that was denied them in their religious upbringing. They may seek out intense, merger-like relationships in an attempt to fill the spiritual void left by their trauma.

On the other hand, they may be terrified of vulnerability and dependence, having learned that relying on others leads to betrayal and pain. They may oscillate between enmeshment and isolation, yearning for intimacy yet struggling to trust.

This relational ambivalence can manifest in various ways. Some survivors may find themselves repeatedly drawn to partners or friends who replicate the dynamics of their abusive religious environment – controlling, shaming, or dogmatic. Others may struggle to set healthy boundaries, having been taught that their needs and desires are unimportant or sinful.

Still others may adopt a stance of rigid self-sufficiency, believing that they can only rely on themselves. They may view relationships as a threat to their hard-won autonomy and fiercely guard against any perceived encroachment on their independence.

Reconstructing Faith: The Spiritual Aftermath of Religious Trauma

Beyond its psychological and relational impact, religious trauma also represents a profound spiritual wound. It is a rupture in one’s relationship with the sacred, a loss of faith not just in a particular religion but in the very possibility of finding meaning and connection in the universe.

For many survivors, the immediate aftermath of religious trauma is marked by a period of intense deconstruction. They may reject all things religious or spiritual, viewing them as inherently oppressive or delusional. They may embrace atheism or agnosticism, finding solace in a purely secular worldview.

However, for some, the longing for spiritual connection and transcendence persists even in the wake of trauma. They may embark on a journey of reconstruction, seeking to build a new relationship with the sacred that is grounded in their own authentic experience and values.

This process of reconstruction can take many forms. Some survivors may explore other religious traditions, finding resonance in teachings or practices that emphasize personal growth, social justice, or direct mystical experience. Others may cobble together their own eclectic spirituality, drawing on elements of psychology, philosophy, art, and nature.

Still others may find spiritual nourishment in secular pursuits – in activism, creativity, or scientific inquiry. They may come to see the sacred not as an external deity or dogma, but as an immanent quality of life itself – the awe and mystery of existence in all its pain and beauty.

Therapeutic Approaches to Religious Trauma Recovery

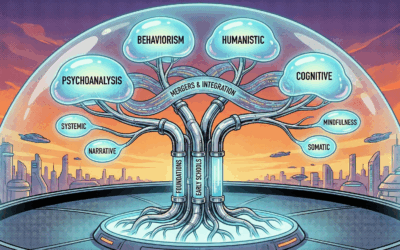

Given the complexity and pervasiveness of religious trauma, healing often requires a multi-faceted, integrative approach. Various therapeutic modalities can offer valuable tools and insights for this journey of recovery.

Depth Psychology: Engaging the Religious Imagination

Depth psychology, with its emphasis on the symbolic, archetypal dimensions of the psyche, can be particularly illuminating in working with religious trauma. Jungian analysis, for example, views the religious impulse as an expression of the collective unconscious – a deeply rooted human need for meaning, wholeness, and transcendence.

From this perspective, religious trauma is not just a personal wound, but a rupture in one’s relationship with the archetypal realm. The abusive religious environment can be seen as a distortion of sacred symbols and energies – a perversion of the “god-image” that resides in the psyche.

Depth psychotherapy can provide a space for survivors to engage with these archetypal dimensions in a healing way. Through practices like dream work, active imagination, and mythological amplification, they can begin to reclaim the religious imagination from the distortions of trauma.

This may involve confronting and transforming internalized images of a punitive, controlling god, and discovering a more benevolent, life-affirming divine presence. It may involve reconnecting with the archetypal energies of the wounded child, the wise elder, or the spiritual warrior within.

Parts Work: Reclaiming the Fragmented Self

As mentioned earlier, religious trauma often leads to a profound fragmentation of the self. Parts-based therapies like Internal Family Systems (IFS) and Ego State Therapy can be powerful tools for healing this inner fracturing.

In working with religiously traumatized parts, the therapist may encounter protector parts that rigidly adhere to religious dogma, believing that it is the only way to ensure safety and belonging. They may encounter wounded child parts that carry the shame, terror, and confusion of abuse. They may encounter rebel parts that reject all things religious with righteous anger.

The goal of parts work is to bring these disparate parts into compassionate dialogue, under the guidance of the wise, unconditionally loving Self. As the parts learn to trust the Self’s leadership, they can begin to release their extreme roles and burdens. The religious protectors can soften their grip, the wounded children can receive the care and validation they needed, and the rebels can channel their energy into healthy self-assertion.

Through this process of inner integration, the survivor can begin to reclaim a sense of wholeness and authenticity. They can develop a more flexible, nuanced relationship with religion and spirituality – one that honors their own truth and experience.

Somatic Approaches: Embodying the Sacred

For many survivors of religious trauma, the body itself is a site of wounding. They may have been subjected to physical abuse or sexual violation in the name of religion. They may have been taught to view their bodies as sinful, shameful, or impure. They may have learned to dissociate from their bodily sensations and needs as a means of coping with trauma.

Somatic therapies like Sensorimotor Psychotherapy and Hakomi can be transformative in helping survivors reconnect with their embodied experience. By gently guiding attention to the body’s sensations, impulses, and movement patterns, these approaches can help to release trapped survival energy and restore a sense of safety and vitality.

For religiously traumatized clients, somatic work may also involve a process of reclaiming the body as a site of the sacred. This may involve exploring practices like yoga, dance, or martial arts that foster a sense of embodied presence and power. It may involve developing rituals that honor the body’s wisdom and resilience – anointing the skin with oil, chanting affirmations of bodily sovereignty, or engaging in sacred movement.

As survivors learn to inhabit their bodies with compassion and reverence, they may begin to experience a sense of spiritual connection that is grounded in their own flesh and blood. They may discover that the sacred is not a distant, disembodied realm, but a pulsing, vivid presence that permeates every cell.

Existential Therapy: Forging Meaning From the Ashes

At its core, religious trauma is an existential crisis – a shattering of one’s fundamental assumptions about the nature of reality, the purpose of existence, and the possibility of redemption. In the wake of this shattering, many survivors find themselves grappling with profound questions of meaning and identity.

Existential therapy can provide a framework for navigating these questions with courage and authenticity. Drawing on the insights of philosophers like Nietzsche, Camus, and Sartre, existential therapists view the human condition as inherently marked by uncertainty, freedom, and responsibility.

From this perspective, the task of healing from religious trauma is not to find a new set of absolute truths or certainties, but to forge meaning and purpose in the face of life’s inherent ambiguity. It is to confront the existential anxieties that religion often serves to assuage – the fear of death, the burden of freedom, the ache of isolation – and to find ways to live with them creatively and courageously.

For some survivors, this may involve a process of values clarification – of discerning what truly matters to them in the absence of religious dictates. It may involve developing a sense of personal ethics grounded in their own experiences of suffering and compassion.

For others, it may involve a process of existential creativity – of using art, music, writing, or other forms of expression to give shape and form to their struggles and insights. It may involve finding ways to contribute to the world, to leave a legacy of healing and resilience.

Ultimately, existential therapy invites survivors to become the authors of their own lives – to take responsibility for the meaning they make of their trauma and their recovery. It is a call to radical honesty, to unflinching self-examination, and to ongoing, courageous engagement with life in all its uncertainty and possibility.

Integrating the Journey

Healing from religious trauma is a profoundly personal and often lifelong journey. It is a process of untangling the threads of abuse and indoctrination that have been woven into the fabric of one’s being, and of reclaiming the sacred strands of self-trust, embodiment, and authentic spirituality.

It is a journey that may lead through dark nights of the soul, through painful confrontations with the past and the unknown. But it is also a journey that can lead to profound transformation – to a more vital, compassionate, and resilient sense of self, and to a more intimate, creative, and joyful engagement with life.

Ultimately, there is no single path or destination for this journey. Each survivor must find their own way, drawing on the resources and practices that resonate most deeply with their own experience and aspirations.

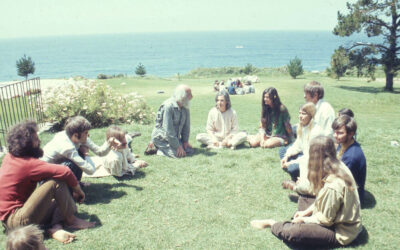

What is essential is that they do not walk this path alone. The support of skilled therapists, compassionate peers, and understanding loved ones can make all the difference in navigating the challenges and celebrating the triumphs of recovery.

May all those who have been wounded by religious trauma find the companions and the courage they need to reclaim their sacred birthright – their innate wholeness, wisdom, and wonder. May they come to know, in the marrow of their bones, that they are not broken, not forsaken, but radiant with the love and light that is their truest nature.

Bibliography:

Attig, T. (2012). How We Grieve: Relearning the World. Oxford University Press.

Corbett, L. (2011). The Sacred Cauldron: Psychotherapy as a Spiritual Practice. Chiron Publications.

Harris, B. (2021). Deceived No More: How Jesus Led Me out of the New Age and into His Arms. Cascade Books.

Johnson, S. (2019). The Myth of the Untroubled Therapist: Private Life, Professional Practice. Routledge.

Kalsched, D. (2013). Trauma and the Soul: A psycho-spiritual approach to human development and its interruption. Routledge.

Loewen, J. A. (2022). The Way of the Wounded Healer: Transforming Your Pain into Purpose. Broadleaf Books.

Miller, A. (1991). Breaking Down the Wall of Silence: The Liberating Experience of Facing Painful Truth. Basic Books.

Romanyshyn, R. D. (2013). The Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind. Spring Journal Books.

Sherwood, L. (2020). Soul-Making: In Between Spaces of Religious Transformation and Growth. Brill.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

0 Comments