Is Religious Cosmology Just the Unlived Life of the Parent?

A commonly quoted fact about astronomy is that the Universe is “expanding”, but that’s not really true. Our universe is nothing more than a giant ball of rules that we can measure. Rules like time, temperature, and distance. We say that the Universe is “expanding” because the amount of space we can measure inside it is increasing. We have no way of knowing what is outside of this ball of rules. It is doubtful that measurements like time and temperature would make much sense there.

-The Spider and the Birdhouse

Jungian psychology posits that the unlived life of the parent is the largest force in a child’s life. It encompasses all the things they don’t bring into therapy because they are off the map, a complete set of things that may contain the client’s shadow and possible potential but contain goals that they don’t even know were possible. Often we learn what makes us loveable from the parent of the opposite sex, or what our caliilng or purpose is. However we learn how to be in the world or our coping style from the parent of the same sex. This is because as children we see the parent of the same sex as a template for how to model our own behavior but the parent of the opposite sex as somethiing that is fundamentally different that we seek to discover how to get the attention of. For example some social workers I have known lean that their purpose is to help others and fight injustice. However their inter personal style is often uncompromising or hostile. THis type of anti social social worker is a common phenomenon that most gradschools now set asside some time for reflection on. This is only one example but there are many dynamics like this in the helping professions where the goal of a person is clashing with the way that they seek to accomplish that goal in the world.

Freud’s Unlived Life

Sigmund Freud‘s life exemplifies this concept. His mother doted on him, believing he was destined for greatness from birth as he was born in a caul, which she took as a sign of his future renown. She delighted in his intelligence and told him from an early age that he would bring their family fame. He was her “little golden Siggy”. In contrast, Freud’s father was a hardworking but passive man who never strove for greatness himself. Freud recalls being shocked and ashamed as a boy when his father was mocked and insulted by anti-Semites, remaining implacable and positive in the face of humiliation.

From his mother, Freud learned that becoming brilliant made him lovable. From his father, he learned to be complacent in confrontation and avoid conflict at all costs. This extreme passivity led Freud to repress his competitive and aggressive energies, which became a major tenet of his psychology. He avoided asserting himself to such a degree that it is difficult to find a case in his biography where conflict with an equal does not result in the dissolution of the relationship entirely. Through out his life Freud remained incapable of direct aggressionor even confrontation. He was however desperate to control the spaces that he inhabited and inable to tollerate descent. He was brilliant and quite capable of maintaining control of mmost rooms with his eloquence and acerbic insight. He ws however blind to his own blindspots and motivations. Many of his own theories were informed by his own emotional enmeshments and avoidances not through unimpeded intuition or psychological clarity.

Jung’s Tumultuous Relationship with Freud

Carl Jung relived his own father wound through his tumultuous encounter with Freud. The two had initially formed a close bond, with Freud seeing Jung as his intellectual heir and the future of the psychoanalytic movement. However, their relationship began to fracture as Jung started to question and diverge from some of Freud’s core theories.

The breaking point came when Jung and Freud were analyzing one of Jung’s dreams together. Jung proposed an interpretation that differed from Freud’s, suggesting that the dream symbolism was not primarily sexual in nature, as Freud insisted, but rather pointed to deeper, more archetypal dimensions of the psyche.

Freud, who could not tolerate any challenge to his intellectual authority, reacted with a kind of psychological collapse. Jung recounts that Freud began looking at him with an expression of intense fear and mistrust, before finally fainting dead away on the floor. When he came to, Freud accused Jung of harboring a “death wish” towards him and abruptly cut off all contact with his once beloved protégé.

For Jung, this traumatic rupture was a recapitulation of his own father’s emotional abandonment and inability to hold space for his son’s developing spiritual and intellectual identity. Jung’s father, a pastor who had lost his faith, could not bear the intensity of his son’s religious questioning and metaphysical speculations, shutting down in the face of Jung’s precocious need for meaning and mythic embodiment.

In the same way, Freud could not accommodate Jung’s urgent need to expand the horizons of psychoanalytic theory beyond the confines of Freud’s own neurotic obsessions and reductive materialism. Freud’s insistence on the primacy of the sexual instinct and the Oedipus complex was, for Jung, a kind of intellectual cage, a refusal to grapple with the deeper, more numinous aspects of the human experience.

The Conflict Over Bog Bodies

During one of their last moments, Jung and Freud found themselves examining the phenomenon of bog bodies – ancient human remains naturally mummified in peat bogs. Jung, ever attuned to the archetypal and mythological dimensions of such artifacts, saw in these preserved corpses a powerful symbol of the human psyche’s relationship to death and the unconscious.

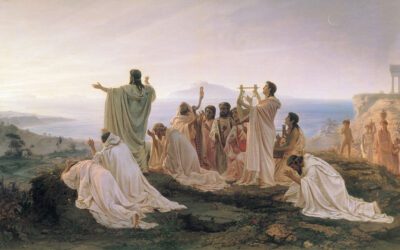

For Jung, the bog bodies represented a kind of “sacral regicide,” a ritualized sacrifice of the king or ruler to appease the chthonic forces of the underworld. He argued that this motif of the “dying and resurrecting god” was a central archetype of the collective unconscious, one that found expression in myths and religious rites across cultures.

Freud, however, was deeply uncomfortable with Jung’s interpretation. As a committed atheist and materialist, he was loath to entertain any notion of a collective unconscious or archetypal symbolism. For Freud, the bog bodies were simply historical curiosities, their significance limited to what they might reveal about the specific societies and individuals that produced them.

More than that, Freud seemed to have a visceral, almost phobic reaction to the very idea of death and mortality. He had suffered from a morbid fear of dying since childhood, a fear that was only exacerbated by the loss of his own father and the existential upheavals of World War I. The thought of confronting death head-on, of staring into the abyss of non-existence, was simply too much for Freud to bear.

So when Jung insisted on the psychological and spiritual significance of the bog bodies, Freud responded with a kind of defensive dismissal. He accused Jung of indulging in “mystical nonsense” and of projecting his own neurotic obsessions onto the archaeological record. He simply could not countenance any challenge to his own theoretical framework, which posited the individual psyche as the sole locus of meaning and motivation.

But beneath this intellectual disagreement lay a deeper, more personal dynamic. Freud, like Jung’s own father, could not tolerate any questioning of his authority or any deviation from his own worldview. For Freud, Jung’s ideas were not just intellectually wrongheaded, but emotionally threatening – a kind of “death wish” directed at the father figure and the psychoanalytic establishment he had created.

In this moment, we see the full force of Freud’s own father complex coming to bear on his relationship with Jung. Just as Freud had learned his own father’s passivity and avoidance of conflict, so he now demanded the same unquestioning obedience from his “son” and heir apparent. Any challenge to that authority, any insistence on Jung’s own intellectual and spiritual autonomy, was experienced by Freud as a kind of psychological annihilation.

This dynamic came to a head in the famous fainting spell that Freud experienced during one of his last meetings with Jung. As Jung recounted the episode, Freud had become increasingly agitated and defensive as their discussion of religion and mythology grew more heated. Finally, overcome by some inner terror or revulsion, Freud collapsed to the floor in a dead faint.

For Jung, this dramatic moment crystallized the fundamental impasse between them. Freud’s inability to confront the deeper, more numinous aspects of the psyche, his refusal to acknowledge the reality of the unconscious and its archetypal manifestations, was not just an intellectual failing, but a symptom of his own unresolved trauma and spiritual arrested development.

In a sense, Freud was reenacting his own father’s abdication of spiritual and emotional authority, his capitulation to the “death” of meaningful religious experience in the face of modernity’s disenchantments. By fainting at the mere suggestion of a realm beyond the ego and its rational categories, Freud was revealing the depths of his own psychic wounds and the unlived life he had inherited from his father.

Jung’s Red Book and the Birth of Analytical Psychology

Jung’s Red Book, formally known as Liber Novus (“The New Book”), is a red leather‐bound folio manuscript crafted by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung between 1915 and about 1930. It recounts and comments upon the author’s imaginative experiences between 1913 and 1916, and is based on manuscripts first drafted by Jung in 1914–15 and 1917.

Jung wrote the Red Book as a way to contain his subsequent split with reality so that it did not devolve into full-blown psychosis or schizophrenia. The work served as both a record of and container for Jung’s confrontation with the unconscious and the archetypal forces within his own psyche.

The creation of the Red Book was, in many ways, the crucible out of which Jung’s entire psychological system emerged. It was through this intensive period of self-analysis and active imagination that Jung began to formulate his core concepts of the collective unconscious, archetypes, the anima and animus, and the individuation process.

In this sense, Jungian therapy itself started as a result of the father wound and the unlived life of the parent that Jung watched his own father refuse to embody. Jung’s father was a priest who had lost his faith but had to continue in his role regardless of his lack of belief for fiinancial and cultural reasons. Jung developed his psychology partially to offer his father a pathway to meaning, wanting him to see that theology could be more like psychology – a living, symbolic experience rather than a set of empty doctrines. Jung spent his career arguing that psychology needed to understand why theology and mythology existed and repeated certain patterns.

Jung’s Archetypal Dreams and Religious Views

Two significant dreams shaped Jung’s views on the limitations of traditional religion. In one, he saw a subterranean phallic god on a throne beneath a cathedral, revealing that religious experience had a profound psychological dimension beyond conventional Christian teachings. In another, he dreamt of God taking a large poop on a church, symbolizing for Jung the failure and decay of religious tradition in providing true transformative meaning to the modern person.

These dreams, along with Jung’s broader experiences, led him to believe that the psyche contains within it the full range of human potential, both light and dark, divine and demonic. For Jung, the goal of psychotherapy was not simply to alleviate symptoms, but to facilitate a process of individuation, whereby the individual comes to integrate these disparate elements into a more whole and authentic self.

This process often involves confronting what Jung called the shadow, those aspects of the personality that have been repressed or denied due to social conditioning or personal shame. It also involves coming to terms with the anima and animus, the contrasexual archetypes that Jung believed exist within each individual’s unconscious.

Jung encountered two warring personalities within himself, a reaction to the unlived spiritual life of his father who was radically repressing one element of his own psyche. Freud, too, could not accept Jung’s offering of a new psychological perspective on religion’s symbols and experiences, likely because Jung had developed his theory of psychological types (which would later become the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator) partially as a peace offering to Freud, in an attempt to explain how their minds processed the world so differently. But just as with Jung’s father, this gesture of reconciliation was rejected.

Jung’s Phenomenological Approach

As a phenomenologist, Jung valued subjectivity and case studies over strict empiricism, believing that objectivity was worthless without a deep understanding of subjectivity and how it colors all of human experience. This is something academic psychology has failed to fully integrate to this day, often dismissing Jung’s work as unscientific without grasping his core epistemological argument.

For Jung, the raw data of psychology was not behavior or cognition as such, but the lived, embodied experience of the individual. He believed that any attempt to understand the psyche must start with a careful and compassionate attention to the unique ways in which each person constructs meaning and navigates their inner world.

The Metaphysical Question of Jungian Psychology

So the provocative question remains – is Jungian psychology or depth psychology in general just a thinly veiled apologetics for a literal faith in religion and spirituality? Many Jungians were indeed raised religious and are pivoting to something that allows them to apply that familiar cosmology to psychology. They argue that at sufficient depth, the psyche reflects universal religious cosmology through the collective unconscious.

There’s a semi-serious joke often heard at Jungian conferences that Jungians are “nice people in recovery” – recovery from avoiding some threatening truth that would have caused major conflict with a parent, until that avoidance became overwhelming, putting them face to face with greater, repressed truths. To fully individuate requires encountering inconvenient, shadow material.

Jung’s radically phenomenological approach leaves all doors open, conceptualizing the raw matter of psychology as a kind of radio antenna that picks up archetypal signals without definitively confirming or denying their metaphysical origin. He used the language and concepts of his time, like the collective unconscious, emerging genetics, physics metaphors, but who can say with certainty where these patterns, archetypes, and perennial philosophies emanate from? Perhaps it’s in the quantum interactions of molecules, as neuroscience continues to speculate.

Critics accused Jung of sneaking metaphysics and literalized religion in through the back door of psychology, but he vehemently rejected this, despising those who retreated into comforting subjectivity as much as he criticized the strict materialists. He once scoffed disparagingly at the New Age as such: “What is the point in people just swaying and intoning ‘vibration’ over and over? That is nothing but ego-fascination and delusion!”

Jung was both limited and empowered by using phenomenology as a singular lens, collaborating with geniuses like physicist Wolfgang Pauli and Albert Einstein when he needed more technical expertise. Jungian therapy today is admittedly a bit of a mess, with some taking his metaphysics too literally and concretely, others rejecting all metaphysics and becoming nihilistic literalists, and most latching onto one aspect of his incredibly vast psychology while downplaying or ignoring the rest.

So, is Jungian psychology merely an eloquent apologetics for a faith-based, supernatural worldview? Is metaphysics always just a projection and argument with a long dead parent? Is it just Catholicism without the rituals? Most Jungian-leaning therapists feel that Jung arrived at the same experiential truths and psycho-spiritual topography that earnest introspection, intuition and inner work would have revealed regardless of creed. But they also acknowledge the impossibility of fully separating one’s familial and cultural religious background from the psychological individuation journey.

Confronting the Unlived Life

Once we leave behind the unlived life of the parent to the degree we can, what do we really see when we honestly look within? Are you living a life true to your own inner vision, however strange or terrifying, or are you still confined to the safe, narrow range that never occurred to you to question or reflect on, that your parents could not conceive of as valid? Are you the hero of your own unfolding myth, or a passive footnote in someone else’s? Are you reading this right now because of a genuine burning drive to understand your own mind, or because your family of origin could never truly consider or discuss these ideas? Whatever the answer, Jung would argue, at least you’re asking the question, which is where the real work begins.

How to Find Unlived Lives of Parents in Your Own Psychology and Cosmology

1. Inherited Spiritual Longing or Deficit

If a parent has an unfulfilled spiritual or religious life, a child may unconsciously inherit that longing or sense of something missing. This feeling of “lack” is often deeply felt in the child’s early years, as the parent may have either rejected their religious beliefs or failed to fully embody them. For example, a parent who had lost faith might still unconsciously wish that their child will somehow bring the sense of meaning or connection that they themselves have lost. The child may pick up on this energy, even if it’s never explicitly spoken about.

Religious energy here can feel like an invisible force that pushes the child to seek meaning, to ask existential questions, or to try to make sense of the world in a way that resonates with what their parent once believed or hoped for. It might also feel like a need to fill the void that the parent left, emotionally or spiritually, and to search for a kind of meaning that the parent was unable to find.

2. The Child as a Spiritual Surrogate

If a parent had unmet spiritual aspirations or an unconscious belief that their own spirituality was somehow flawed, the child might come to feel as though they are being subtly placed in the role of a “spiritual heir.” For instance, if a parent repressed their own religious feelings—maybe because of trauma or disbelief—they might unconsciously wish for their child to embody those unexpressed spiritual dimensions.

Religious energy here might feel like a heavy mantle being placed upon the child, as if the child must “complete” what the parent couldn’t, or “save” the parent’s spiritual narrative. This might manifest as a feeling of spiritual responsibility, a desire to live up to some unspoken (or even unconscious) expectation, or an overwhelming sense that the child must somehow transcend or heal the parent’s spiritual struggles. The child might unconsciously develop a religious framework that feels more like a duty or burden than a personal calling—reflecting the parent’s unmet needs rather than their own.

3. Transference of Parent’s Shadow and Beliefs

Jung often spoke of the shadow, those parts of the self that are repressed or rejected. The parent’s repressed spiritual or religious dimensions (such as fear of faith, loss of belief, or the inability to embrace certain divine or mythological ideas) can become part of the child’s shadow. This can create a complex religious cosmology, where the child feels a push-pull relationship to religion: they are drawn to it but also afraid of it, because it is wrapped up in their parent’s unresolved issues.

For example, if a parent had deep-seated fears about divine retribution or guilt (but never expressed them), the child may begin to feel a deep, unconscious fear of religious authority, punishment, or failure, even if they haven’t directly experienced these feelings. Religious energy in this case feels ambivalent or paradoxical: the child may feel simultaneously drawn to and repelled by religious ideas, haunted by the specter of the parent’s unresolved spiritual conflicts.

4. Religious Exploration as a Search for Wholeness

If a parent never explored or fully embraced their own spiritual path—perhaps rejecting religion or unable to connect to deeper meaning—the child might take on an almost unconscious task of spiritual exploration. This can feel like a drive to seek answers to questions of meaning, truth, and purpose that the parent either couldn’t or didn’t want to answer.

Religious energy here can manifest as a deeply felt yearning, a search for something greater than oneself, or a compulsion to explore spiritual traditions and myths that feel like they hold the key to healing or wholeness. In this sense, the child might feel that their personal growth or transformation is connected to reclaiming something their parent lost or abandoned—a sense of spiritual completion or fulfillment.

5. Inherited Archetypes and Mythic Themes

Jung believed that there are universal patterns and symbols within the human psyche—archetypes—that reflect the shared human experience. If a parent has an unlived life involving religious or spiritual themes, the child may inherit those archetypes and live them out unconsciously. This could involve the child unconsciously identifying with archetypes such as the “wounded healer,” the “lost soul,” or the “searching pilgrim.”

Religious energy here might feel like an inner compulsion to embody these mythic figures in one’s own life, whether through creative expression, psychological struggles, or spiritual seeking. The child may feel drawn to religious or spiritual narratives that mirror the struggles, desires, and unfulfilled potentials of the parent, and in doing so, come to live out these archetypes in their own life. This might lead to the child viewing their own life as a kind of mythic journey—one that is unconsciously tied to the parent’s unresolved, unlived story.

6. Emotional Intensity and Sacred Meaning

For some children, the unlived life of a parent manifests as a sense of profound emotional intensity around religious or spiritual issues. This might manifest as an overwhelming urge to find or create meaning, a deep longing for connection, or a heightened sensitivity to spiritual or mystical experiences. If a parent had intense religious feelings—either positive or negative—that were not fully explored, the child may feel an unconscious pull toward these same intense emotional states.

Religious energy here feels like a deep emotional current that leads the child to search for meaning or transcendence. This might also be expressed through an unconscious alignment with particular religious or mystical traditions that mirror the parent’s own emotional state, whether it’s fervent belief, spiritual despair, or the rejection of spirituality altogether. The child may feel the need to fill the emotional void left by the parent’s repressed or avoided spiritual life, and this search can take on a sacred, almost divine quality.

7. Rejection and Rebellion Against Parental Cosmology

In some cases, the child may reject the spiritual or religious beliefs of their parent entirely. This rejection might occur if the parent’s own religious life was stifling, authoritarian, or rigid. However, this rebellion still carries an unconscious charge—it isn’t a neutral stance, but rather a reaction to the parent’s unexpressed or repressed religious energy. In rejecting the parent’s beliefs, the child may unconsciously be re-enacting the parent’s struggles with meaning, or they may create a religious cosmology that is, in some ways, an exaggerated contrast to what the parent tried to impose.

Religious energy here feels like a force of defiance—an intense spiritual rebellion that still feels like an engagement with the religious dynamics of the parent. Even though the child rejects the parent’s religious framework, they are still shaped by it, and in doing so, they create a new cosmology that often reflects the parent’s unresolved conflicts with faith.

The Child’s Spiritual Journey

In summary, the unlived life of the parent shapes the child’s spiritual and religious worldview in profound, often unconscious ways. The child may feel a deep unacknowledged longing for something their parent could not embody—a longing for meaning, for transcendence, or for spiritual fulfillment. This religious energy can be a source of deep emotional drive, spiritual questing, or even rebellion. The key point is that this energy often isn’t purely personal—it reflects the unresolved dimensions of the parent’s life that have been passed down and internalized by the child. This inheritance shapes the child’s spiritual journey and their unconscious cosmology, whether they accept, reject, or reshape it.

Jungian therapy seeks to bring this unconscious material into consciousness, allowing the individual to break free from these inherited, unexamined patterns and find their own path to wholeness and spiritual understanding. By acknowledging the influence of the unlived life of the parent, the child can begin to form a more authentic cosmology, one that is not simply a repetition of the parent’s unresolved spiritual struggles but a true reflection of their own evolving sense of meaning and connection.

0 Comments