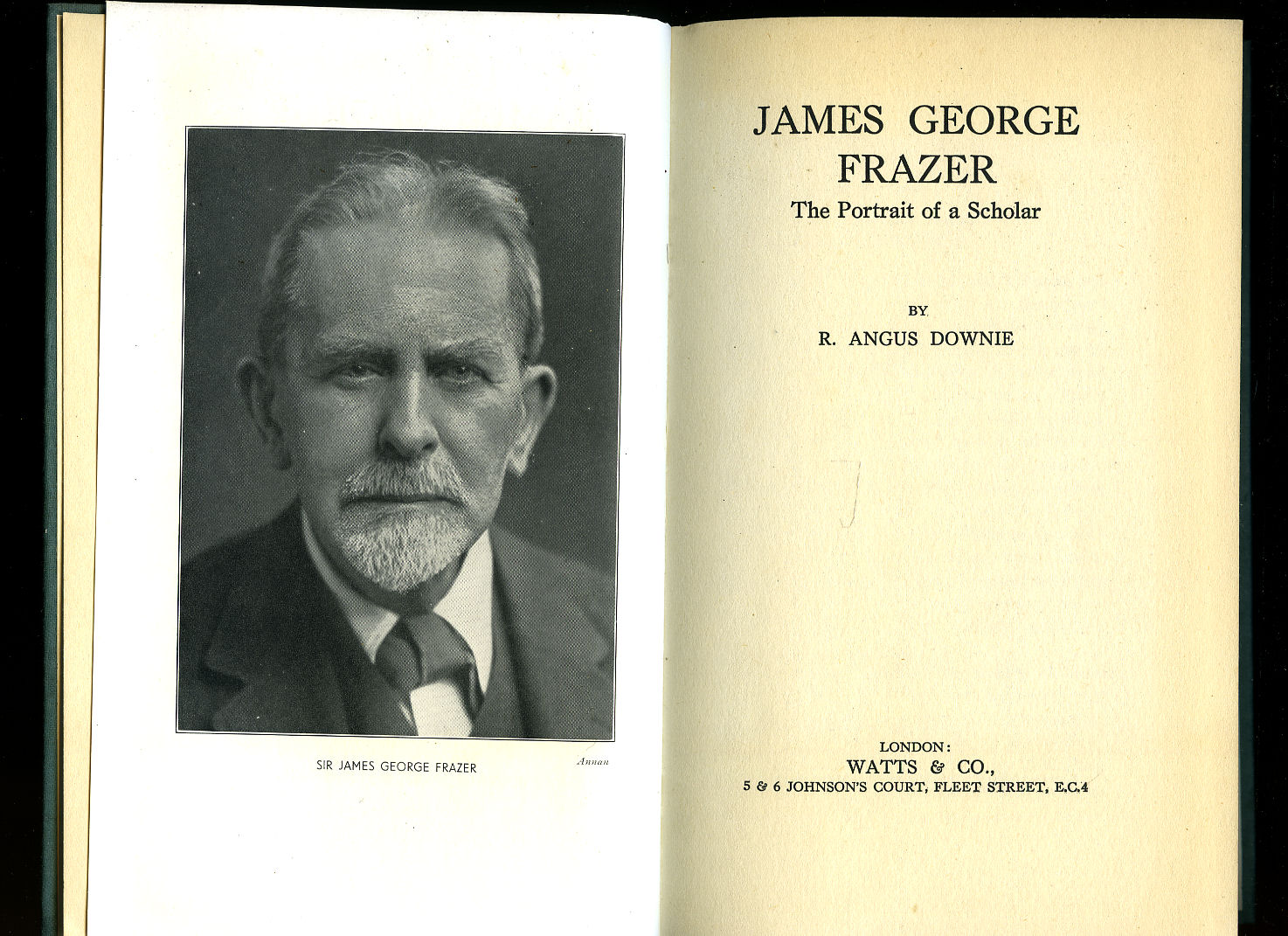

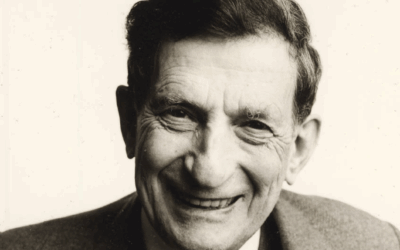

Who was James George Frazer?

James George Frazer (1854-1941) was a groundbreaking Scottish anthropologist, folklorist, and classical scholar whose work laid the foundations for modern anthropology, psychology, and comparative religious studies. Best known for his monumental study of myth and religion, The Golden Bough, Frazer pioneered the comparative method in anthropology, seeking to unveil universal patterns and evolutionary sequences in human beliefs and practices across cultures. His ideas not only shaped the emerging fields of social science in the early 20th century, but also exerted a profound influence on depth psychology, literature, and modernist thought.

The Comparative Method and the Study of Culture

Frazer’s most enduring contribution to anthropology was his development and application of the comparative method. Inspired by the work of Edward Tylor and the evolutionary theories of his time, Frazer sought to collect, classify, and compare ethnographic data from around the world, discerning underlying similarities and tracing developmental sequences in cultural forms.

In The Golden Bough, originally published in two volumes in 1890 and later expanded to twelve volumes, Frazer surveyed a vast range of myths, rituals, and religious practices, from fertility rites and human sacrifice to magic, taboo, and the worship of sacred kings. He argued that all societies pass through three stages of belief – magic, religion, and science – each characterized by a different understanding of causality and relationship to nature.

While Frazer’s evolutionary schema and some of his specific conclusions have been critiqued by later anthropologists, his comparative approach helped to establish cultural anthropology as a science and laid the groundwork for cross-cultural analysis. By assembling such a wealth of ethnographic material and subjecting it to systematic comparison, Frazer demonstrated the power of the comparative method for revealing patterns and generating insights into the diversity and commonalities of human cultures.

Myth, Ritual, and the Roots of Religion

Central to Frazer’s analysis in The Golden Bough was the relationship between myth, ritual, and the origins of religion. Frazer argued that myth and ritual were intimately entwined in primitive cultures, with myths serving to explain and justify rituals, and rituals acting out the sacred stories told in myths.

Frazer paid particular attention to the widespread motifs of the dying and resurrecting god, the sacrificial king, and the scapegoat – themes he traced across multiple mythologies and religious traditions. He saw in these recurrent patterns the origins of religion in fertility cults centered on the cycle of death and rebirth in nature.

For Frazer, primitive religions arose from magical practices aimed at controlling the forces of nature and securing the fertility of crops, animals, and humans. As these magical rites evolved into institutionalized rituals and priestly hierarchies, they gave rise to more complex religious systems, with myths elaborating the cosmologies and sacred histories that undergirded ritual practices.

While some of Frazer’s specific theories about the origins and evolution of religion have been challenged, his insights into the intimate relationship between myth and ritual and the importance of fertility motifs in early religions have had an enduring influence. His work helped to establish the study of mythology and comparative religion as vital fields of inquiry and paved the way for later theorists like Mircea Eliade, Joseph Campbell, and Carl Jung.

The Resonance with Depth Psychology

Perhaps one of the most remarkable aspects of Frazer’s legacy is the way his ideas resonated with and influenced the emerging field of depth psychology in the early 20th century. Both Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung were deeply impacted by The Golden Bough, finding in its comparative analysis of myths and symbols a key to understanding the workings of the unconscious mind.

Freud drew on Frazer’s work in his explorations of the Oedipus complex, totemism, and the savage roots of civilization in books like Totem and Taboo. He saw in the universal motifs that Frazer traced – patricide, incest, sacrifice – evidence for his theories of infantile sexuality and the repression of primitive impulses in the development of culture.

For Jung, Frazer’s revelations of the ubiquity of archetypal themes across cultures provided crucial support for his theory of the collective unconscious. The recurring motifs of the divine child, the sacrificial king, and the hieros gamos that Frazer documented resonated with the archetypal patterns Jung discerned in dreams, myths, and psychopathology. Frazer’s explorations of the primitive roots of religion also harmonized with Jung’s view of the religious instinct as springing from the depths of the psyche.

Both Freud and Jung found in Frazer a kindred spirit – a fellow explorer of the deep strata of the mind and the origins of human culture. While they took Frazer’s insights in different directions, both used his comparative ethnographic material as a lens for examining the psyche and a means of connecting individual psychology to the larger matrix of human history and culture.

In this way, Frazer helped to build vital bridges between anthropology and psychology, showing how the study of culture and the study of the mind could illuminate each other. His influence on depth psychology, and on the modernist imagination more broadly, attests to the power of his vision and the fecundity of his thought.

The Golden Bough and the Modernist Imagination

Beyond his impact on anthropology and psychology, Frazer’s work also had a profound effect on literature, art, and the modernist sensibility. The Golden Bough became a key text for poets, novelists, and artists in the early 20th century, who found in its densely layered symbolism and revelations of primitive ritual a new vocabulary for the modern imagination.

T.S. Eliot famously acknowledged the influence of The Golden Bough on his poem The Waste Land, which weaves together motifs of fertility, sacrifice, and the Fisher King drawn from Frazer’s work. James Joyce similarly drew on Frazer in Ulysses, using the structure of the fertility rituals Frazer analyzed to shape the novel’s symbolic texture.

In the visual arts, painters like Pablo Picasso and Jackson Pollock found inspiration in the primal energies and mythic resonances that Frazer’s work evoked. The motifs of the sacrificial king, the sacred tree, and the labyrinth that recur throughout The Golden Bough became key symbols for the Surrealist and Abstract Expressionist movements.

For many modernist artists and thinkers, Frazer’s revelations of the savage substrate of culture offered a way of tapping into the elemental forces of the psyche and reimagining the modern world. His comparative method, with its juxtapositions of the primitive and the civilized, the sacred and the profane, provided a model for the modernist collage aesthetic and the mythical method of writers like Eliot and Joyce.

In this way, Frazer’s influence extended far beyond the academy, shaping the cultural imagination of the 20th century. His ideas permeated the zeitgeist, offering new ways of seeing the world and the self in relation to the deep strata of history and the collective unconscious.

Frazer’s Legacy and Continuing Relevance

While some of Frazer’s specific theories and evolutionary assumptions have been critiqued by later scholars, his larger vision and the questions he posed continue to resonate. His comparative approach, his fascination with the primitive roots of culture, and his insight into the power of myth and symbol anticipated many of the key themes of 20th-century thought.

In anthropology, Frazer’s comparative method laid the groundwork for later theorists like Claude Lévi-Strauss, who used structuralist analysis to discern the deep patterns underlying myths and cultural forms. In religious studies, Frazer’s exploration of the mythic underpinnings of Christianity and other world religions paved the way for the work of scholars like Mircea Eliade and Joseph Campbell.

In psychology, Frazer’s influence can be seen not only in the work of Freud and Jung, but also in later thinkers like James Hillman and the archetypal school. Hillman’s explorations of the “poetic basis of mind” and the role of myth in shaping psychic life owe much to Frazer’s pioneering studies.

Perhaps most importantly, Frazer’s work continues to inspire us to look beneath the surface of our cultural forms and to seek the deeper patterns that connect us to our primitive roots. His revelations of the mythic substrates of religion, his insight into the intimate relationship between ritual and the rhythms of nature, and his discernment of archetypal themes across cultures offer enduring resources for the study of the human mind and spirit.

At a time when we are grappling with the ecological crisis and seeking to reforge our connection to the living world, Frazer’s explorations of the primal roots of culture seem newly relevant. His vision of the continuity between primitive magic and modern science, and his insights into the role of ritual in attuning human communities to the cycles of nature, offer potent resources for reimagining our relationship to the more-than-human world.

Frazer’s legacy, then, is not just a matter of historical interest but a living resource for our time. As we seek to navigate the challenges of the 21st century, his comparative insights and psychological acumen offer vital tools for understanding ourselves and our world. By following the golden bough that Frazer extended to us, we may yet find our way back to the sacred groves of the imagination and the regenerative wellsprings of culture.

0 Comments