Our fight or flight response was a gift that kept us alive while we were living in the wild. When we heard a tiger growl, we either had to fight a tiger or run away from a tiger. The first thing that happens during the fight or flight response is that our mind loses our connection to our body. If you are going to fight a tiger or run fifty miles away from one, you don’t want to feel what is happening to your body.

The fight or flight system is less helpful when it is being activated by fear of social situations or by traumatic memories in our past. When our fight or flight system becomes activated and there is no one to fight and nowhere to run, we can not discharge the enormous amount of emotional energy our brains are carrying. When we become disconnected from our bodies we are not aware of the physiological responses that are accelerating the stress response.

We do not feel our heart rate skyrocketing. We do not feel our bodies warm and start to sweat as blood moves into the small capillaries across the top level of our skin. We do not feel our muscles store tension and lock up. These physical responses, when we are not aware of them, cause us emotional distress. If we do not take steps to interrupt the stress response our minds will continue to obsess and our thoughts to race. This experience of fear, directed at a problem we cannot solve by more thinking, will make us feel powerless, the world feel unsafe, and the future feel hopeless.

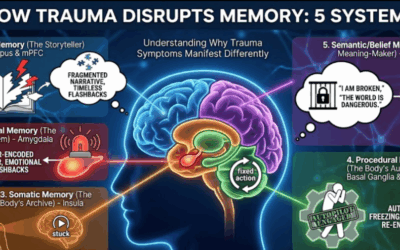

When we are experiencing trauma our brain is in such an activated state that it is not able to record memories correctly. Traumatic memories are written into the brain improperly. These memories are experienced somatically and emotionally as if they were currently happening to us every time we recall the memory. Intellectually we may know that these events occurred in the past, but emotionally and physically we experience the sensations of the trauma in the present. Normal healthy memories we can recall as past events that we are able to think about, form new ideas about, and have new perspectives on.

Because the traumatic memory is something that we are forced to relive every time we access it, we are not able to integrate these memories into a larger story and are stuck with the beliefs that we held about ourselves and our surroundings during the trauma. These trauma memories or traumatic fears are “stuck” or “black and white”. We are not able to understand the trauma as an event that is no longer our current reality. The part of our brain that is activated during our fight or flight response is not able to tell time. The stuck memory will activate the amygdala without activating the other parts of the brain we need to think and reason. These stuck memories are the reason that we panic and dissociate. Reliving the emotions and beliefs from a past experience makes us feel powerless, as we attempt to escape from an event that is no longer taking place.

This inability to think about the trauma without experiencing it means that we are trapped within the distressing feelings we had about ourselves during the trauma. This is why we feel powerless, hopeless, responsible, or dirty, even though the incident is no longer taking place. These negative beliefs about the self during the trauma, are often the most lasting and damaging part of the traumatic incident. Recognizing and combating being overwhelmed by the trauma belief is the first step towards pulling yourself away from the incident and back into your current surroundings and current reality. There is no one way to achieve this. However EMDR is one of the fastest and most evidence based techniques that we have found so far.

EMDR, or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, is a therapeutic technique where a mental health practitioner will have you move your eyes in a way that uses both parts of your brain to become activated and process memory. The left half of the brain is our logical and detail oriented center. It is active when we implement a scientific concept or calculate an equation. Non verbal memories, such as those found in PTSD and trauma patients, are stored in the prefrontal cortex on this half of the brain. The right half of the brain is creative and abstract. It can have realizations and understand new perspectives. During REM sleep when we dream our eyes move back and forth as the right half of our brain helps us to process and understand the logical content of our thoughts and experiences.

In PTSD and trauma patients, it is the right side of the brain that logically and methodically experiences the event of the trauma and our beliefs about it over and over again. By using EMDR to activate both parts of the brain while a clinician directs you to think about the traumatic experience, we can involve the left half of the brain as well. Just like in REM sleep, EMDR allows us to form new understandings and ideas about events stored in our logical memory. Just as REM sleep allows the dreamer to create new realities from their past experience, EMDR can help us let go of the things that trauma forced us to believe about ourselves at one time.

By bringing the creative and resilient part of our cognition into the trauma experience, we can understand new things, create new perspectives on the experience and feel less trapped in our beliefs at the time of the trauma. Additionally, EMDR allows the “stuck” memory to be reprocessed and rewritten into the brain correctly as an event that we can understand as a part of our past and not our current reality. Even though we cannot change the fact that trauma occurs, we can change the way that we think and feel about the trauma into a more adaptable way.

Bibliography:

van der Kolk, Bessel A. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books, 2014.

Shapiro, Francine. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy, Third Edition: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. Guilford Press, 2017.

Levine, Peter A. Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. North Atlantic Books, 1997.

Porges, Stephen W. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. W.W. Norton & Company, 2011.

Lanius, Ruth, et al. Healing the Traumatized Self: Consciousness, Neuroscience, Treatment. W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Further Reading:

Rothschild, Babette. The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment. W.W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Damasio, Antonio. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt Brace, 1999.

Siegel, Daniel J. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. Guilford Press, 2015.

Emerson, David, and Elizabeth Hopper. Overcoming Trauma and PTSD. New Harbinger Publications, 2011.

Mate, Gabor. When the Body Says No: Exploring the Stress-Disease Connection. Wiley, 2011.

Arden, John B., and Lloyd Linford. Brain-Based Therapy with Adults: Evidence-Based Treatment for Everyday Practice. Wiley, 2008.

Ogden, Pat, and Janina Fisher. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment. W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Briere, John, and Catherine Scott. Principles of Trauma Therapy: A Guide to Symptoms, Evaluation, and Treatment. SAGE Publications, 2014.

Van Der Hart, Onno, et al. The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatization. W.W. Norton & Company, 2006.

0 Comments