The Subcortical Brain and the Roots of the Unconscious

The Subcortical Brain and the Roots of the Unconscious

The human mind is a vast and complex landscape, with conscious awareness representing only the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface lies a realm of unconscious processes, instincts, and archetypal patterns that profoundly shape our perceptions, emotions, and behaviors. In recent years, advances in neuroscience and depth psychology have begun to shed light on the evolutionary roots of the unconscious mind and its intimate connection to the subcortical brain structures.

This blog post will take a deep dive into how the rapid processing of the subcortical brain gives rise to unconscious phenomena, the role of the prefrontal cortex in filtering and gating this information, and the implications for understanding trauma, intuition, and the practice of psychotherapy. We’ll explore cutting-edge theories and research, trace the evolutionary origins of key brain structures, and consider how this knowledge can inform a more integrative, whole-person approach to mental health and well-being.

So let’s embark on this journey into the depths of the mind, starting with the very foundations of unconscious processing in the subcortical brain.

The Parietal Eye in Reptilian Ancestors

To really understand the origins of the intuitive capacities of the human mind, and their relationship to trauma responses, we need to go back in time to the age of reptiles. Many ancient reptiles, such as certain lizards and the ancestors of modern birds, possessed a unique sensory organ known as the parietal eye or “third eye”.

This parietal eye was positioned on the top of the head, sitting just beneath a translucent scale that allowed light to penetrate through to light-sensitive cells. Physically, it looked somewhat like a small, primitive eye, with a lens, retina and nerve fibers connecting it to the brain. However, its function was quite different from that of the two main eyes.

Rather than forming detailed visual images, the parietal eye was attuned to detecting changes in light intensity and polarization, as well as sensing magnetic fields. This allowed reptiles to orient themselves in space, detect the position of the sun even on cloudy days, and maintain circadian rhythms and seasonal cycles. In essence, the parietal eye provided a kind of ‘ambient’ sensory awareness, a background sense of the animal’s position and orientation in the environment.

Neurologically, the parietal eye was intimately connected with the epithalamus, a region of the diencephalon or “interbrain” that serves as a relay station for sensory and motor signals. Within the epithalamus, the key structure was the pineal gland, a small, pinecone-shaped organ that received direct input from the parietal eye.

The pineal gland, in turn, was rich in light-sensitive cells and had neural connections to other parts of the limbic system and brainstem involved in circadian regulation, hormone secretion, and behavioral responses to environmental stimuli. So in these ancient reptiles, there was a direct pathway from the parietal eye to the pineal gland to the subcortical brain regions involved in instinctive, unconscious processing.

Functionally, this parietal eye-pineal-limbic axis seems to have provided a kind of ‘deep intuition’ or non-conceptual awareness of subtle energetic and temporal patterns in the environment. By tuning into the cycles of light and dark, the Earth’s magnetism, and perhaps even other forces and fields that we are unaware of, reptiles could adjust their behavior and physiology to stay in harmony with their ecosystem.

This wasn’t a verbal, rational kind of knowledge, but a felt sense, an instinct, a gut feeling about what to do and when to do it. And critically, this intuitive awareness flowed from the parietal eye to the subcortical brain without needing to pass through the ‘higher’ cortical centers involved in conscious cognition. It was a direct line from the environment to the primal, instinctive core of the nervous system.

The Shift to the Pineal-Limbic System and the Dual Nature of Intuition and Trauma

As evolution progressed and the parietal eye began to regress in early mammals, the pineal gland and its deep connections to the limbic system and subcortical brain took on new functions and significance. While the pineal gland lost its direct photosensitivity, it retained a key role in regulating circadian rhythms, sleep-wake cycles, and states of consciousness through its secretion of the hormone melatonin.

However, the pineal gland’s influence goes beyond mere physiological regulation. Situated as a nexus between the ancient, reptilian brain structures and the more recently evolved limbic and neocortical regions, the pineal gland and its associated networks serve as a sort of “primal antenna” for subtle environmental and internal cues. This deep, embodied wisdom of the pineal-limbic system often manifests as intuitive “gut feelings”, “hunches”, or instinctive responses that seem to arise from a place beyond conscious thought.

Interestingly, this intuitive mode of knowing shares many qualities with the spatial awareness functions of the parietal eye in lower vertebrates. Just as the parietal eye provided a direct, non-visual pathway for detecting changes in light, movement, and orientation in the environment, the pineal-limbic system offers a kind of “felt sense” of the world, an immediate, pre-verbal attunement to the energetic and emotional landscape within and around us.

In a sense, the situational awareness capacities that were once mediated by the parietal eye have been internalized and transformed into a more abstract, intuitive form of perception. Rather than detecting physical changes in the external environment, the pineal-limbic system is attuned to the subtler fluctuations of meaning, valence, and felt sense in our experiential world.

This transition reflects the larger shift from the concrete, sensorimotor cognition of our early vertebrate ancestors to the more symbolic, conceptual cognition of the human mind. As the parietal eye atrophied and its functions were subsumed by deeper brain structures like the superior colliculus and the posterior parietal cortex, the raw data of sensory perception was increasingly filtered through layers of associative memory, emotional valence, and narrative meaning.

The result is a kind of “mapping” of the external world onto the internal landscape of the psyche, a projection of our own unconscious contents and complexes onto the screen of reality. In this way, the intuitive wisdom of the pineal-limbic system can be both a source of profound insight and a potential trap, leading us to mistake our own unresolved fears, desires, and traumas for objective truth.

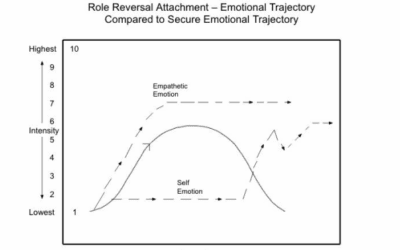

This is where the dual nature of intuition and trauma becomes apparent. On one hand, the pineal-limbic system and its associated networks are the wellspring of our deepest creativity, empathy, and spiritual connection. When this system is functioning optimally, we have a strong sense of attunement to ourselves, others, and the world around us. We can access a kind of “direct knowing” that bypasses the discursive intellect and speaks to us in the language of symbol, metaphor, and felt meaning.

On the other hand, this same system is also the seat of our most primal wounds and reactive patterns. When the limbic system and brainstem are overwhelmed by traumatic stress, they can become chronically hyperaroused or dissociated, leading to a state of dysregulation and disconnection from the body and the environment. In this state, the individual may feel trapped in a kind of “survival mode”, constantly scanning for threats and unable to access higher-order capacities for reasoning, perspective-taking, and self-reflection.

This is where Carl Jung‘s concept of the “shadow” becomes particularly relevant. For Jung, the shadow represents the repressed, rejected, or unconscious aspects of the personality that are split off from the conscious ego and projected onto the outside world. These shadow contents are often rooted in early experiences of trauma, neglect, or overwhelming emotion, which are too painful or threatening to integrate into our conscious self-image.

When we are possessed by a complex or a traumatic shadow, we may find ourselves repeatedly drawn into destructive patterns of thought and behavior, as if caught in the gravitational pull of a black hole. We may feel a deep sense of shame, worthlessness, or fear that colors all of our experiences and relationships. And critically, we may mistake the voice of the wounded shadow for the voice of our intuitive wisdom, leading us to make choices and interpretations that perpetuate our suffering.

The task of healing and integration, then, is to bring these shadow contents into the light of conscious awareness, so that they can be met with compassion, understanding, and choice. This is the essence of Jung’s individuation process – the lifelong journey of becoming more fully ourselves, by embracing and integrating all of our disparate parts and potentials.

In the context of trauma, this often involves revisiting and reworking the painful experiences that have been encoded in the limbic system and the body. By slowly and safely titrating the activation of the traumatic memories, and by providing a corrective experience of attunement, empowerment, and completion, the individual can begin to discharge the frozen energy of the trauma response and restore a sense of coherence and resilience.

This is where embodied, experiential therapies like Somatic Experiencing, EMDR, and Brainspotting can be incredibly effective. By working directly with the felt sense of the body and the implicit memories stored in the subcortical brain, these approaches aim to gently uncouple the automatic, reflexive responses of the trauma system from the adaptive, creative capacities of the whole self.

As the individual becomes more skilled at tracking and regulating their own internal states, they can begin to develop a more nuanced and reliable sense of intuition. Rather than being hijacked by the trauma responses of the limbic system, they can learn to discern between the true signals of their organismic wisdom and the false alarms of their wounded past. They can cultivate a kind of “sacred pause” between stimulus and response, in which they have the space to consult multiple ways of knowing before taking action.

In this view, the pineal gland and its associated networks represent not just a remnant of our evolutionary history, but a vital bridge between the primal and the transcendent, the instinctual and the intuitive, the personal and the collective. By honoring and integrating these multiple ways of knowing, we can begin to access a more fully human way of being in the world – one that embraces the full spectrum of our embodied experience and empowers us to co-create a more just, compassionate, and sustainable future.

Sensory Gating, Intuition, and Schizophrenia: A Continuum of Perception

The evolutionary transition from the parietal eye to the pineal-limbic system reveals a fundamental aspect of human perception: the delicate balance between filtering sensory input and maintaining an open channel to the unconscious. This balance is at the heart of what modern neuroscience refers to as sensory gating, a crucial mechanism that determines how much raw sensory information enters conscious awareness and how much is inhibited to prevent overload. Sensory gating is deeply tied to intuition, as both involve the selective attunement to certain patterns while filtering out irrelevant noise. However, when this system becomes dysregulated, it can manifest in extreme forms, such as in schizophrenia, where the filtering mechanisms break down, allowing an overwhelming flood of unconscious material into awareness.

The Role of the Thalamus and the Sensory Gating Mechanism

The thalamus, a central relay station in the brain, plays a critical role in sensory gating by regulating the flow of sensory data to the cortex. In a well-functioning system, the thalamus acts as a filter, permitting only the most salient sensory stimuli to reach conscious awareness while dampening extraneous signals. This process allows individuals to maintain a stable perception of reality, focusing on relevant stimuli while ignoring irrelevant or misleading information.

However, in certain states—whether due to trauma, heightened intuitive perception, or neurological dysfunction—the gating mechanism may either become too restrictive, suppressing essential signals, or too porous, allowing an unmediated flood of sensory input. The latter scenario is particularly relevant to schizophrenia, where deficits in thalamic filtering contribute to the intrusion of unconscious material, hallucinations, and an altered perception of reality.

Intuition as an Adaptive Function of Sensory Gating

At its core, intuition relies on a finely tuned sensory gating system that selectively permits deep unconscious insights to enter awareness. When functioning optimally, this system enables individuals to sense patterns and make decisions based on implicit knowledge rather than explicit reasoning. This process is likely rooted in the same subcortical circuits that once mediated the parietal eye’s awareness of light cycles and environmental changes. Just as the parietal eye provided reptiles with a direct, non-conceptual awareness of their surroundings, human intuition functions as a rapid, holistic mode of perception that draws from unconscious pattern recognition.

Research on intuitive decision-making suggests that experienced professionals—such as firefighters or surgeons—can make split-second, accurate judgments based on minimal explicit information. This is possible because their brains have learned to recognize deep patterns over time, allowing for rapid, unconscious processing of complex scenarios. However, such intuitive faculties require a properly calibrated sensory gating system that permits meaningful insights while filtering out noise and irrelevant stimuli.

Sensory Gating Deficits in Schizophrenia and the Overload of the Unconscious

Schizophrenia provides a compelling case study of what happens when the sensory gating system fails. Individuals with schizophrenia often exhibit a breakdown in the thalamic filtering of sensory input, leading to excessive stimulation and difficulty distinguishing between internal and external reality. Auditory hallucinations, for example, may result from the intrusion of subconscious thoughts into conscious awareness without the usual gating mechanisms to distinguish them as self-generated.

Neuroscientific research has shown that individuals with schizophrenia exhibit reduced pre-pulse inhibition (PPI), a measure of sensory gating that reflects the brain’s ability to suppress an exaggerated response to stimuli. This deficiency suggests that their nervous systems are overwhelmed by an excess of raw, unfiltered sensory and unconscious material. The breakdown of these barriers creates an altered experience of reality in which symbolic, archetypal, and emotionally charged material floods into perception, often in the form of hallucinations, delusions, and heightened sensitivity to environmental cues.

In many ways, schizophrenia represents an extreme example of what happens when the unconscious becomes too accessible. Unlike the refined intuition of a well-regulated mind, where unconscious material is gradually integrated into awareness in a structured manner, schizophrenia allows unmediated access to deep psychic content without the necessary cognitive or emotional scaffolding to make sense of it. Jungian psychology has long proposed that psychosis represents a state in which archetypal material overwhelms the ego, creating an experience akin to mythological possession.

Trauma, Sensory Gating, and Hypervigilance

Interestingly, trauma can also dysregulate sensory gating, though often in the opposite direction. Instead of an unfiltered flood of unconscious material, trauma survivors may develop excessively restrictive gating mechanisms as a protective response. This hypervigilance, often seen in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), leads to a narrowed focus of attention where only threat-related stimuli penetrate awareness, while broader perceptual awareness is diminished. This creates a chronic state of scanning for danger, impairing the ability to engage with the environment in an open, intuitive way.

Moreover, some trauma survivors experience transient episodes of sensory gating failure, particularly under stress, leading to dissociation, intrusive memories, or hallucinatory experiences reminiscent of schizophrenia. In such cases, traumatic imprints stored in the limbic system may bypass the usual cortical filtering mechanisms, intruding into consciousness in the form of flashbacks, body memories, or overwhelming emotional states.

Trauma, Intuition and the Primal Brain

The pathway from parietal to pineal system in evoloution is of course highly speculative. I am a social worker not a anthropologist, evoloutionary biologist or neurologist. However these pathways are neuroplausible based on the existing scholarship and potential usefull for understanding what is effective in therapy. This evolutionary history becomes particularly relevant when we consider the impact of trauma on the human psyche. Traumatic experiences, especially those that occur early in life or that are prolonged and severe, have been shown to profoundly alter the structure and function of the subcortical brain regions, including the amygdala, hippocampus and limbic system.

These changes can lead to a chronic state of hyperarousal and reactivity, where the individual becomes hypersensitive to potential threats and can easily become overwhelmed by stress and intense emotions. In a sense, trauma ‘rewires’ the primal brain to be stuck in a kind of perpetual fight-flight-freeze mode, always scanning for danger and ready to react at a moment’s notice.

Interestingly, some researchers have suggested that this state of post-traumatic hypervigilance may in some ways resemble the heightened sensory awareness of our reptilian ancestors. Just as the parietal eye was attuned to subtle changes in light and magnetic fields, the traumatized individual becomes acutely attuned to subtle cues of potential danger in their environment, whether that’s a certain tone of voice, a particular facial expression, or a vague sense of unease.

Of course, in the case of trauma, this heightened awareness is often maladaptive, leading to false alarms and overreactions that can be debilitating. But it points to the fact that trauma doesn’t just impact the ‘higher’ cognitive functions of the brain, but can penetrate into the deepest, most primal layers of our being.

At the same time, this connection between trauma and the subcortical brain may also hold keys for healing and transformation. Just as the parietal eye once provided a direct conduit for intuitive, embodied wisdom to flow from the environment to the organism, therapeutic practices that work with the body and the non-verbal mind may be able to tap into this ancient capacity for self-regulation and resilience.

These defensive strategies can take on a life of their own, operating outside of conscious awareness and masquerading as intuitive truths. For example, an individual who was repeatedly betrayed or abandoned in childhood may develop a deep-seated belief that they are unlovable and that others cannot be trusted. As an adult, they may find themselves constantly drawn to unavailable or abusive partners, mistaking their traumatized attachment patterns for romantic chemistry or soulmate connections.

Similarly, individuals who have experienced religious or spiritual abuse may struggle to differentiate between the voice of their own inner guidance and the internalized voice of the abuser. They may feel a profound sense of shame, unworthiness, or fear around their spiritual longings, believing that they are fundamentally flawed or sinful for having such desires. Alternatively, they may become rigidly attached to certain beliefs or practices, using them as a way to control their environment and avoid the uncertainty and vulnerability of genuine spiritual exploration.

In the therapeutic process, it is crucial to help traumatized individuals learn to distinguish between the adaptive wisdom of their intuition and the maladaptive patterns of their trauma. This involves a gradual process of reconnecting with the body, learning to tolerate and regulate intense emotions, and developing a more nuanced and compassionate understanding of the self.

A Timeline of Parietal-Pineal Evolution

The Parietal Eye in Ancient Reptiles (300-200 million years ago)

In the early evolution of reptiles, the parietal eye first appears as a photoreceptive organ connected to the pineal gland in the epithalamus. This “third eye” likely served a variety of functions:

- Detecting changes in light intensity and day length to regulate circadian rhythms and seasonal cycles.

- Sensing the polarization and angle of sunlight to aid in navigation and orientation.

- Possibly perceiving magnetic fields and other subtle environmental cues.

At this stage, the parietal eye provided a direct, non-visual channel for information to flow from the environment to the primal, subcortical brain regions involved in instinct, emotion, and bodily regulation. This allowed reptiles to respond quickly and automatically to changing conditions, without the need for complex cognition or problem-solving.

The Transition to Mammals (200-100 million years ago)

As mammals evolved from their reptilian ancestors, the parietal eye began to regress and internalize. Several factors likely contributed to this shift:

- The evolution of fur and changes in skull morphology made an external eye less viable.

- The nocturnal habits of early mammals reduced the usefulness of a light-sensitive organ.

- The expansion of the neocortex allowed for more sophisticated processing of sensory information from the main visual pathway.

However, while the parietal eye itself disappeared, the pineal gland and its connections to the limbic system and brainstem remained intact. The pineal gland took on a new role as a neuroendocrine transducer, converting environmental signals (primarily light) into chemical outputs like melatonin to regulate circadian rhythms.

The Rise of the Neocortex (100-10 million years ago)

With the evolution of primates and other mammalian lineages, the neocortex underwent massive expansion and differentiation. This allowed for the development of complex cognitive abilities like:

- Sensory integration and perceptual binding

- Memory and learning

- Language and symbolic thought

- Abstract reasoning and problem-solving

As the neocortex took on these “higher” functions, the subcortical brain regions became increasingly dedicated to “lower” functions like instinct, emotion, and bodily regulation. The flow of information from the environment to the primal brain became more indirect, filtered through the thalamus and the cortical sensory areas.

This created a kind of split between the “rational” mind of the neocortex and the “emotional” mind of the limbic system and brainstem. While this division of labor allowed for greater cognitive flexibility and problem-solving power, it also set the stage for potential conflicts between reason and instinct, thought and feeling.

The Human Condition (10 million years ago – present)

With the emergence of human consciousness and culture, the split between the neocortex and the subcortical brain became even more pronounced. As Paul MacLean argued with his “triune brain” model, the human mind is a kind of “palimpsest” of evolutionary layers:

- The “reptilian complex” of the brainstem and cerebellum, governing instinct and survival functions.

- The “paleomammalian complex” of the limbic system, mediating emotion and memory.

- The “neomammalian complex” of the neocortex, enabling language, abstraction, and self-awareness.

While these layers are deeply interconnected, they can also come into conflict, as when our rational goals clash with our emotional impulses, or when traumatic stress overwhelms our cognitive capacities.

According to Erich Neumann, this evolutionary history is recapitulated in the psychological development of each individual. The infant begins in a state of “uroboric” fusion with the mother and the environment, dominated by instinct and emotion. Only gradually does the ego emerge from this primal unity, as the neocortex develops and the child learns to differentiate self from other, subject from object.

However, this process of ego development is never complete, and the adult mind remains shaped by the deep, unconscious forces of the subcortical brain. For Neumann, the goal of psychological growth is not to repress or transcend these forces, but to integrate them with the conscious ego in a dynamic, creative balance.

In this view, the pineal gland and its associated structures can be seen as a kind of “vestigial” bridge between the modern, rational mind and the ancient, intuitive wisdom of the body. While we no longer have a literal “third eye”, we still possess the capacity to tap into the subtle cues and signals of our environment, to respond with instinct and feeling as well as reason and analysis.

However, as both MacLean and Neumann recognized, this integration is not easy to achieve. In the modern world, we are often cut off from the rhythms and cues of the natural environment that shaped our evolutionary development. Our culture values rational, linear thinking over intuitive, embodied knowing. And the stresses and traumas of life can create deep rifts between our conscious and unconscious minds, leading to psychological conflict and suffering.

Simplified Timeline

To help clarify this complex evolutionary story, here’s a simplified timeline of the key events in the transformation of the parietal eye system into the pineal-limbic complex:

- 300-400 million years ago: The parietal eye first appears in the ancestors of modern reptiles and birds. It is connected to the pineal gland and serves as a ‘third eye’ for detecting light, shadow and magnetic fields.

- 200-300 million years ago: As reptiles diversify into various niches, the parietal eye becomes more or less prominent in different lineages. In some, like modern lizards, it remains well-developed; in others, like snakes, it regresses.

- 150-200 million years ago: With the emergence of early mammals, the parietal eye starts to disappear, likely due to lifestyle changes (nocturnality, burrowing) and the expansion of the cerebral cortex. However, the pineal gland and its connections to the limbic system remain intact.

- 50-150 million years ago: In early primates, the pineal gland continues to function as a light-sensitive organ, regulating circadian rhythms and seasonal cycles. It also maintains its role as a conduit for non-verbal, intuitive information to flow from the environment to the subcortical brain.

- 1-10 million years ago: In early hominins and humans, the pineal gland becomes less directly light-sensitive, but still plays a key role in regulating sleep-wake cycles and modulating states of consciousness. Its connections to the limbic system and brainstem are preserved, allowing for the flow of embodied, intuitive wisdom.

- Present day: While the pineal gland is no longer a literal ‘third eye’, it remains a key part of the subcortical brain, influencing our physiology, behavior and conscious experience in subtle but profound ways. Trauma, stress and other challenges can disrupt the healthy functioning of this system, leading to states of dysregulation and disconnection. However, somatic and embodied therapies may offer a path to reconnect with the wisdom of the primal mind and restore a sense of wholeness and resilience.

Of course, this is a highly simplified timeline, and there are many nuances and variations across different species and individuals. But it hopefully provides a rough sketch of the deep evolutionary roots of the pineal gland and its role in mediating between the environment, the body and the mind.

Telling the Difference Between Trauma and Intuition

Activating the Primal Brain: Somatic and Experiential Therapies

As we’ve seen, the pineal gland and its associated subcortical networks represent a kind of “fossil record” of our evolutionary history, a vestigial link to the ancient, pre-rational ways of knowing and being that characterized our distant ancestors. While the parietal eye itself has long since disappeared, the deep brain structures it once served continue to shape our experience in profound ways, particularly in the realm of instinct, emotion, and embodied awareness.

This understanding has important implications for the theory and practice of psychotherapy, particularly for approaches that emphasize the role of the body and the non-verbal, experiential dimensions of healing. By engaging these primal systems directly, rather than relying solely on verbal, cognitive interventions, these therapies may be able to access and transform deeply rooted patterns of trauma, stress, and maladaptive behavior.

Let’s look at a few specific examples:

Brainspotting

Brainspotting is a more recent therapy that combines elements of EMDR, somatic experiencing, and mindfulness-based approaches. Developed by David Grand, brainspotting involves identifying specific eye positions or “brainspots” that seem to activate or resonate with the client’s traumatic memories or emotional states.

By holding these brainspots with focused attention and mindful awareness, the client can gently process and release the underlying neurophysiological patterns that maintain the trauma. Brainspotting seems to work by engaging the subcortical brain directly, bypassing the verbal, analytical mind and accessing the deeper, more primal layers of emotional and somatic experience.

One possible explanation for the effectiveness of brainspotting is that the specific eye positions may correspond to different “fields” or “vectors” of subcortical activation, reflecting the evolutionary layering of the brain. For example, a brainspot that triggers a sense of fear or anger may be engaging the amygdala and the limbic system, while a brainspot that evokes a feeling of collapse or shut-down may be tapping into the immobilization response of the brainstem.

By systematically exploring and integrating these different brainspots, the client may be able to build a more coherent, resilient sense of self, one that encompasses the full range of their evolutionary heritage. In a sense, brainspotting can be seen as a kind of “archeology of the soul”, a way of excavating and healing the deep, buried strata of the psyche.

Embodied and Experiential Approaches

Of course, these are just a few examples of the many therapies and practices that work with the body and the subcortical brain in the service of healing and growth. Other approaches, like sensorimotor psychotherapy, hakomi, focusing, and authentic movement, also prioritize the non-verbal, experiential dimensions of the therapeutic process.

What these approaches have in common is a recognition that the rational, analytical mind is not the whole story when it comes to human consciousness and change. By engaging the body, the senses, and the primal, instinctive layers of the brain, these therapies aim to access a deeper, more fundamental level of being, one that is rooted in our evolutionary history and our ancestral ways of knowing.

This is not to say that cognitive, insight-oriented approaches are not important or valuable – far from it. The development of the neocortex and its capacities for language, abstraction, and self-reflection has been a crucial step in our evolution as a species, and has opened up vast new realms of creativity, innovation, and meaning-making.

However, as MacLean and Neumann recognized, the higher functions of the neocortex can also become disconnected or dissociated from the deeper, more primal layers of the brain, leading to a kind of “disembodied” consciousness that is cut off from its own instinctive roots. In this state, we may become overly identified with our thoughts, beliefs, and narratives, losing touch with the felt sense of our own aliveness and the living world around us.

The goal of embodied and experiential therapies, then, is not to bypass or transcend the rational mind, but rather to bring it into a more integrated, harmonious relationship with the rest of the brain and body. By cultivating a more direct, immediate connection with our sensory experience, our emotional states, and our intuitive ways of knowing, we can begin to bridge the gap between reason and instinct, mind and body, self and world.

Ultimately, this may be the key to a truly holistic and integrative model of human development and potential – one that honors the full spectrum of our evolutionary heritage, from the ancient wisdom of the reptilian brain to the abstract reasoning of the neocortex, and everything in between. By embracing and integrating all of these layers of our being, we can begin to actualize a more whole, authentic, and creative way of living, one that reflects the vast intelligence and resilience of the embodied mind.

Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT)

Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT), developed by Dr. Steven Vazquez, is a therapeutic approach that utilizes light, color wavelengths, and eye movement to facilitate emotional and physiological healing. Unlike traditional talk therapies, ETT operates on the premise that exposure to specific wavelengths of light can directly influence neural activity, modulate mood states, and even restructure deep-seated trauma patterns within the brain.

ETT’s foundation lies in the understanding that the human brain is highly responsive to visual stimuli, particularly light and color. The therapy utilizes specialized equipment to expose clients to varying frequencies of light, often in conjunction with guided emotional processing. This exposure is believed to influence the hypothalamus, a key regulatory center that governs autonomic and emotional responses, as well as the pineal gland, which plays a significant role in circadian rhythms and neurohormonal balance.

In therapeutic sessions, clients are guided to focus on specific emotional concerns while engaging in light-stimulated processes. This combination of sensory input and cognitive focus facilitates the rapid transformation of emotional states, often allowing individuals to access and resolve deeply buried trauma with remarkable speed. The process is particularly effective for conditions such as PTSD, depression, and anxiety, which are often rooted in dysregulated subcortical activity.

A key element of ETT is its capacity to access and recondition implicit memories—those deeply stored experiences that influence behavior and perception beyond conscious awareness. By targeting these memories at a neurophysiological level, ETT helps to disentangle trauma responses from present-moment intuition, fostering a clearer and more accurate sense of self-awareness. This distinction is crucial, as many individuals struggling with trauma may mistake hypervigilance or fear-based responses for intuition. Through ETT, clients can recalibrate their nervous system, making it easier to differentiate between trauma-driven reactivity and genuine intuitive knowing.

Furthermore, ETT’s use of eye movement techniques shares similarities with EMDR and Brainspotting but adds the element of photonic stimulation, which appears to enhance neuroplasticity and deepen the therapeutic process. By integrating light, movement, and emotional processing, ETT not only releases stored trauma but also strengthens the brain’s ability to access higher-order states of awareness, creativity, and embodied presence.

Jungian Analysis

Jungian analysis, rooted in the work of Carl Gustav Jung, offers another profound approach to distinguishing between trauma and intuition by exploring the unconscious through symbolic meaning, archetypes, and deep psychological integration. Unlike many trauma-focused therapies that emphasize physiological regulation, Jungian analysis delves into the narrative and mythological structures that shape an individual’s psyche, providing a pathway to self-discovery and individuation.

Central to Jungian thought is the idea that the unconscious contains both personal and collective dimensions. The personal unconscious holds repressed memories and unresolved emotional conflicts, while the collective unconscious consists of inherited archetypal patterns that shape human experience. Trauma often creates psychological complexes—autonomous emotional patterns that distort perception and behavior. These complexes can interfere with intuition, creating projections, anxieties, and compulsions that mask as inner knowing. By working through these complexes in analysis, individuals can discern the difference between fear-based reactivity and authentic intuition.

Jungian therapy often employs active imagination, dream analysis, and symbolic interpretation to bring unconscious material into conscious awareness. Dreams, in particular, serve as a bridge between the unconscious and waking life, often revealing underlying conflicts and deep wisdom. Many individuals with unresolved trauma experience recurring themes in their dreams, such as being chased, trapped, or lost. By working through these symbols with a trained Jungian analyst, one can unravel the hidden messages within these dreams and integrate fragmented aspects of the psyche.

Another key concept in Jungian analysis is the differentiation between the ego and the Self. The ego represents the conscious sense of identity, while the Self is the totality of the psyche, encompassing both conscious and unconscious elements. Trauma can fracture the connection between the ego and the Self, causing individuals to operate from a place of fear, rigidity, or dissociation. Intuition, in contrast, emerges from a well-integrated psyche in which the ego is in dialogue with the deeper wisdom of the Self. Jungian analysis seeks to restore this connection through symbolic engagement, inner work, and the therapeutic relationship.

Shadow work is another essential aspect of Jungian analysis that aids in distinguishing trauma from intuition. The shadow consists of repressed or denied aspects of the self—both negative and positive. Many trauma survivors project their disowned emotions onto others or the world at large, mistaking unresolved wounds for intuitive insight. By confronting and integrating shadow aspects, individuals reclaim lost parts of themselves, leading to a clearer and more authentic inner guidance system.

Ultimately, Jungian analysis provides a long-term, transformative path toward understanding the intricate layers of the psyche. By engaging with symbols, mythology, and unconscious processes, individuals can move beyond trauma-driven perception and access a deeper, more reliable form of intuition—one that is not reactive or fear-based, but grounded in the wholeness of the Self.

In Summation

Somatic Experiencing (SE)

Developed by Peter Levine, SE is a body-oriented approach to healing trauma that draws on insights from neuroscience, ethology, and indigenous healing practices. The core idea of SE is that trauma is primarily a physiological phenomenon, a disruption of the natural rhythms and responses of the autonomic nervous system.

When we experience a traumatic event, our bodies mobilize a massive amount of energy to defend against the threat. However, if this energy is not fully discharged, it can become “stuck” in the nervous system, leading to a range of symptoms like hypervigilance, dissociation, and emotional reactivity.

SE works by gently guiding the client’s attention to the felt sense of the body, particularly to the subtle sensations and impulses that arise in response to trauma-related cues. By staying with these sensations and allowing them to unfold and resolve in their own time, the client can gradually release the trapped energy and restore a sense of safety and equilibrium.

Interestingly, many of the key principles of SE seem to reflect an intuitive understanding of the evolutionary role of the subcortical brain. The emphasis on instinctive, sensory-motor responses, the attention to subtle shifts in arousal and energy, the trust in the body’s innate wisdom and self-regulating capacities – all of these align with the idea of a primal, embodied intelligence that operates beneath the level of conscious awareness.

In a sense, SE can be seen as a way of “reverse engineering” the ancient survival responses of the reptilian brain, using the language of sensation and movement to communicate with and modulate these deep, instinctive patterns. By working with the body directly, rather than trying to override or control it with the rational mind, SE may be able to access a more fundamental level of healing and transformation.

EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing)

EMDR is another widely used trauma therapy that incorporates somatic and experiential elements. Developed by Francine Shapiro, EMDR involves guiding the client through a series of lateral eye movements or other bilateral stimulation (like tapping or auditory tones) while simultaneously holding the memory or image of a traumatic event.

The exact mechanisms of EMDR are still debated, but one theory is that the bilateral stimulation helps to “unfreeze” the traumatic memory from its isolated, fragmented state in the subcortical brain, allowing it to be reprocessed and integrated with the broader context of the person’s life experiences.

Some researchers have suggested that the eye movements in EMDR may specifically target the superior colliculus, a midbrain structure involved in orienting responses and the coordination of eye and head movements. The superior colliculus has rich connections with the amygdala and other limbic areas, and may play a key role in the rapid, unconscious processing of emotional stimuli.

By repeatedly activating this subcortical pathway in the context of a safe, supportive therapeutic relationship, EMDR may help to “rewire” the brain’s threat detection and response systems, reducing the automatic reactivity and hyperarousal associated with trauma.

Notably, the use of rhythmic, alternating stimulation in EMDR also seems to echo some of the primal, cyclical rhythms of the natural world, like the oscillation of day and night, the ebb and flow of the tides, the contraction and relaxation of the breath. By entraining the brain to these ancient, evolutionary rhythms, EMDR may be tapping into a deep, regenerative capacity of the nervous system, one that evolved long before the advent of language or rational cognition.

In this post, we’ve taken a deep dive into the fascinating evolutionary history of the parietal eye and its transformation into the pineal gland complex in modern humans. We’ve seen how this ancient sensory system, originally attuned to detecting light, shadow and magnetic fields, has been repurposed over millions of years to serve as a conduit for non-verbal, intuitive information to flow from the environment to the primal brain.

We’ve also explored how trauma can disrupt this delicate system, leading to states of chronic hyperarousal and disconnection from embodied wisdom. But we’ve also seen how somatic and embodied therapies may offer a path to reconnect with the intelligence of the subcortical brain and restore a sense of safety and wholeness.

Ultimately, the story of the parietal eye and the pineal gland is a story about the deep roots of human consciousness and the intimate connection between the body, the environment and the mind. By honoring these primal aspects of our being and cultivating practices that engage them directly, we may be able to tap into a profound source of healing, resilience and transformation.

It’s a reminder that even as we evolve and develop new capacities for rational thought and abstract reasoning, we are still deeply embedded in the wisdom of our ancestral past. And by reconnecting with that wisdom, whether through therapy, meditation, or simply spending time in nature, we may be able to find a greater sense of balance, purpose and wholeness in our lives.

Bibliography:

Arendt, J. (1998). Melatonin and the pineal gland: influence on mammalian seasonal and circadian physiology. Reviews of reproduction, 3(1), 13-22.

Bókkon, I., & Mallick, B. N. (2017). Schizophrenia: redox regulation and volume neurotransmission. Current neuropharmacology, 15(2), 289-300.

Eadie, M. J. (2003). A pathology of the animal spirits—the clinical neurology of Thomas Willis (1621–1675): Part I–Background, and disorders of intrinsically normal animal spirits. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 10(1), 14-29.

Golan, J., Arad, M., Sebag, J., & Greenblatt, C. L. (2008). The pineal gland and schizophrenia: a review. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 22(7), 788-797.

Janak, P. H., & Tye, K. M. (2015). From circuits to behaviour in the amygdala. Nature, 517(7534), 284-292.

Lacalli, T. C. (2018). Amphioxus, motion detection, and the evolutionary origin of the vertebrate retinotectal map. EvoDevo, 9(1), 1-11.

Lamb, T. D. (2013). Evolution of phototransduction, vertebrate photoreceptors and retina. Progress in retinal and eye research, 36, 52-119.

Macchi, M. M., & Bruce, J. N. (2004). Human pineal physiology and functional significance of melatonin. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology, 25(3-4), 177-195.

Metzger, M., Souza, R., Lima, L. B., Bueno, D., Gonçalves, L., Sego, C., … & Herculano-Houzel, S. (2021). Expansion of transient subplate neurons and axons in the developing human forebrain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(30).

Morriss-Kay, G. M. (2021). The evolution of the mammalian and human forebrain. Journal of Anatomy, 238(5), 1084-1102.

Ojala, D., Amara, D. P., & Schaffer, D. V. (2015). Adeno-associated virus vectors and neurological gene therapy. The Neuroscientist, 21(1), 84-98.

Ralph, C. L., Young, S., Gettinger, R., & O’Shea, T. J. (1999). Does the manatee have a pineal body?. Biological Rhythm Research, 30(1), 74-80.

Takahashi, J. S. (2017). Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nature Reviews Genetics, 18(3), 164-179.

Tan, D. X., Xu, B., Zhou, X., & Reiter, R. J. (2018). Pineal calcification, melatonin production, aging, associated health consequences and rejuvenation of the pineal gland. Molecules, 23(2), 301.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Vollrath, L. (1981). The pineal organ. In The Pineal Organ. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Vollrath, L. (1984). Functional anatomy of the human pineal gland. The pineal gland, 285-322.

Welsh, D. K., Takahashi, J. S., & Kay, S. A. (2010). Suprachiasmatic nucleus: cell autonomy and network properties. Annual review of physiology, 72, 551-577.

Willis, G. L., & Armstrong, S. M. (1999). A therapeutic role for melatonin antagonism in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Physiology & behavior, 66(5), 785-795.

Wurtman, R. J., Axelrod, J., & Kelly, D. E. (1968). The pineal gland. Academic Press.

Yehuda, R., & LeDoux, J. (2007). Response variation following trauma: a translational neuroscience approach to understanding PTSD. Neuron, 56(1), 19-32.

Youngstedt, S. D., & Kripke, D. F. (2007). Does bright light have an anxiolytic effect?—an open trial. BMC psychiatry, 7(1), 1-5.

Zeman, A., & Reading, P. (2005). The science of sleep. Clinical medicine, 5(2), 97-101.

Zlotos, D. P., Jockers, R., Cecon, E., Rivara, S., & Witt-Enderby, P. A. (2014). MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors: ligands, models, oligomers, and therapeutic potential. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 57(8), 3161-3185.

Zrenner, C. (1985). Theories of pineal function from classical antiquity to 1900: a history. Pineal Research Reviews, 3, 1-40.

0 Comments